Chelsa Gurkin is Acting Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security at the U.S. Government Accountability Office. This post is based on her recent testimony before the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services.

I am pleased to be here today to discuss our prior work on strategies for increasing diversity on corporate boards of directors. Corporate boards take actions and make decisions that not only affect the lives of millions of employees and consumers, but also influence the policies and practices of the global marketplace. Many organizations have recognized the importance of recruiting and retaining women and minorities for key positions to improve business or organizational performance and better meet the needs of a diverse customer base. Academic researchers and others have highlighted the importance of diversity among board directors to increase the range of perspectives for decision making, among other benefits. Our prior work, however, found challenges to increasing diversity on boards and underscored the importance of identifying strategies that can improve or accelerate efforts to increase the representation of women and minorities on boards. Our reports on workforce and board diversity span multiple years and cover different industries, types of boards, and workers. These include reports examining the diversity of publicly-traded company boards (corporate boards) and the boards of federally chartered banks, such as the Federal Home Loan Banks. [1] We have also published reports on workforce diversity in the financial services and technology sectors, including representation of women and minorities in management positions, and practices to address workforce diversity challenges. [2]

My remarks today address (1) the extent of diversity on corporate and Federal Home Loan Bank boards, (2) factors that hinder diversity on these boards, and (3) strategies for increasing board diversity. These objectives are primarily based on two prior reports on board diversity issued in 2015 and 2019. [3] In those reports, we used multiple methodologies to develop the findings, conclusions, and recommendations. For example, for our 2015 report on the representation of women on corporate boards, we analyzed a dataset on board directors at companies in the S&P Composite 1500 from 1997 through 2014 to provide descriptive statistics. [4] To obtain stakeholders’ views on various strategies for increasing the number of women on boards, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 19 stakeholders, including chief executive officers (CEO), board directors, and investors. While the views of the individuals we interviewed represent a range of perspectives, they cannot be generalized to the universe of CEOs, board directors, or investors. We also interviewed officials from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and reviewed the SEC’s disclosure requirements on board diversity. For the 2019 report on Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLBank) diversity, we analyzed gender, race, and ethnicity data self-reported by board directors in the banks’ annual reports to their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, as of the end of calendar years 2015, 2016, and 2017. To obtain information on the challenges FHLBanks face and practices they use to recruit and maintain diverse boards, we interviewed Federal Housing Finance Agency and FHLBank staff and a nongeneralizable sample of external stakeholders knowledgeable about diversity. This statement also includes examples of challenges and practices from our 2011 report on board diversity and governance issues at the Federal Reserve Banks. [5] A more detailed discussion of the objectives, scope, and methodologies, including our assessment of data reliability, is available in each report.

The work upon which this statement is based was conducted in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Board Directors’ Roles and Responsibilities

Our previous work on board diversity describes some of the different roles and responsibilities of corporate and FHLBank boards and their directors.

Public Company Corporate Boards

Generally, a public company’s [6] board of directors is responsible for managing the business and affairs of the corporation, including representing shareholders and protecting their interests. [7] Corporate boards vary in size. According to a 2018 report that includes board characteristics of large public companies, the average board has about 11 directors. [8] Corporate boards are responsible for overseeing management performance and selecting and overseeing the company’s CEO, among other duties. Directors are compensated for their work. The board generally establishes committees to enhance the effectiveness of its oversight and focus on matters of particular concern, such as an audit committee and a nominating committee to recommend potential directors to the full board.

FHLBank Boards

Our previous reports on board diversity include a recent report on the FHLBank System. [9] Each of its 11 federally chartered banks has a board of directors and is cooperatively owned by its member institutions, including commercial and community banks, thrifts, credit unions, and insurance companies. Each bank’s board of directors is made up of directors from member institutions and independent directors (who cannot be affiliated with the bank’s member institutions or recipients of loans). As of October 2018, each FHLBank board had 14-24 directors, for a total of 194 directors. The Federal Home Loan Bank Act, as amended by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, and its regulations set forth a number of requirements for FHLBank directors, including skills, term length, and the percentage who are member and independent directors.

Benefits of Board Diversity

Research we reviewed for our prior work cited several benefits associated with board diversity. For example, academic and business research has shown that the broader range of perspectives represented in diverse groups requires individuals to work harder to come to a consensus, which can lead to better decisions. [10] In addition, research has shown that diverse boards make good business sense because they may better reflect a company’s employee and customer base, and can tap into the skills of a broader talent pool. Some research has found that diverse boards that include women may have a positive impact on a company’s financial performance, but other research has not. These mixed results depend, in part, on differences in how financial performance was defined and what methodologies were used. [11]

Our Prior Work Found Women and Minorities Were Underrepresented on Boards

Our prior work found the number of women on corporate boards and the number of women and minorities on FHLBank boards had increased, but their representation generally continued to lag behind men and whites, respectively. While the data sources, methodologies, and time frames for our analyses were different for each report, the trends were fairly consistent.

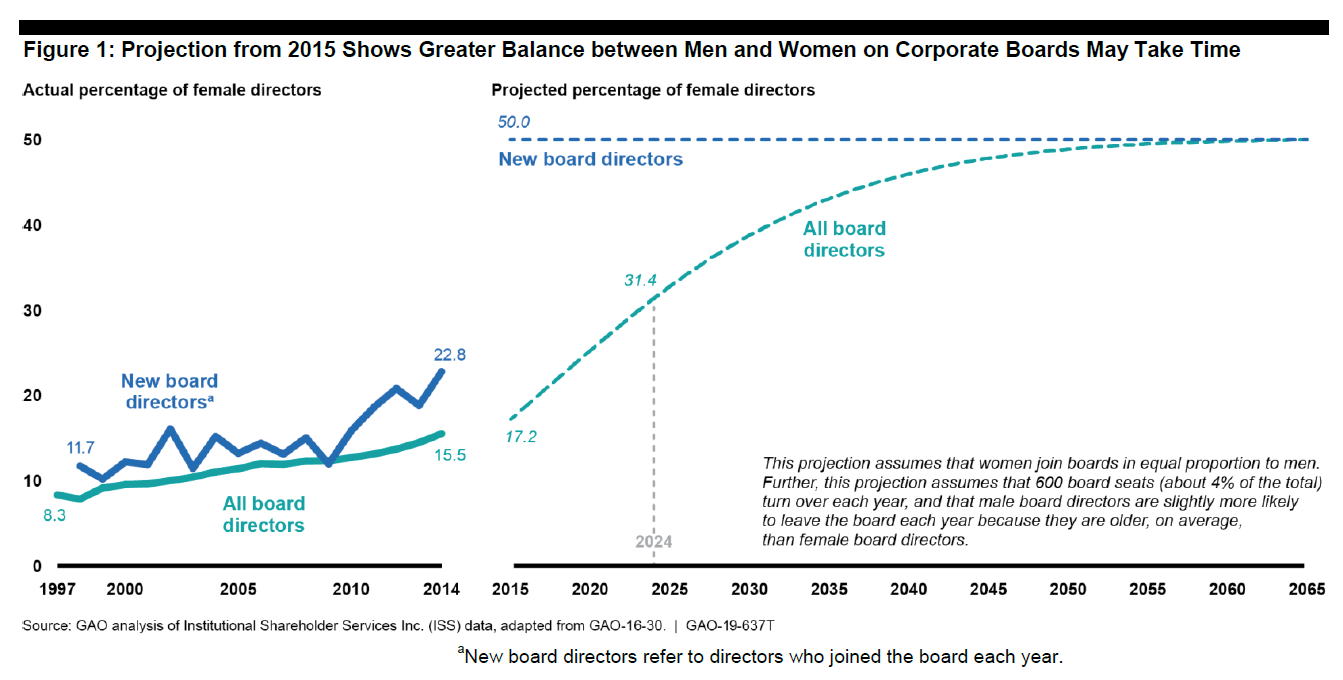

In our 2015 report, we analyzed companies in the S&P 1500 and found that women’s representation on corporate boards increased steadily from about 8 percent in 1997 to about 16 percent in 2014. However, despite the increase in women’s representation on boards, we estimated that it could still take decades for women to achieve balance with men. When we projected the representation of women on boards into the future assuming that women join boards in equal proportion to men—a proportion more than twice what we had observed—we estimated it could take about 10 years from 2014 for women to comprise 30 percent of board directors and more than 40 years for the number of women directors to match the number of men directors (see fig. 1). [12]

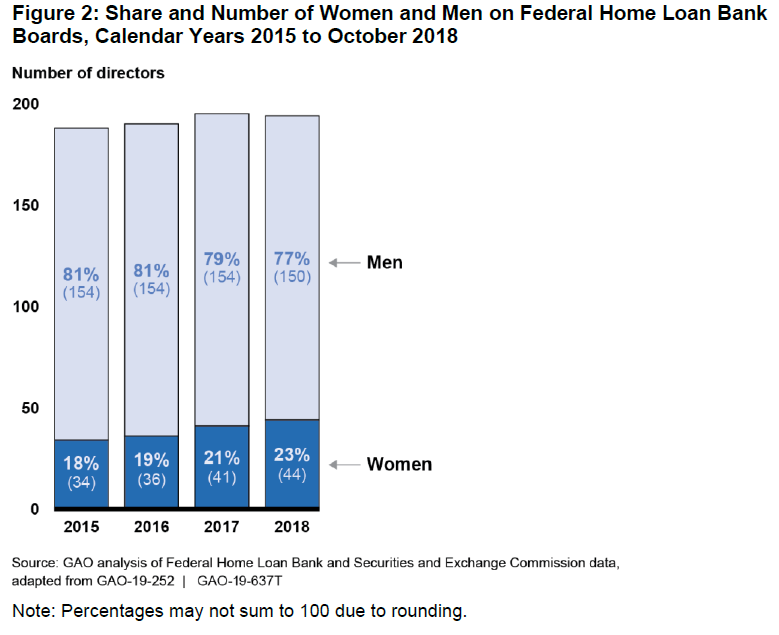

Similarly, in our 2019 report on FHLBank board diversity, we found that the share of women board directors increased from 2015 to October 2018 but that women still comprised less than 25 percent of FHLBank board directors as of 2018 (see fig. 2).

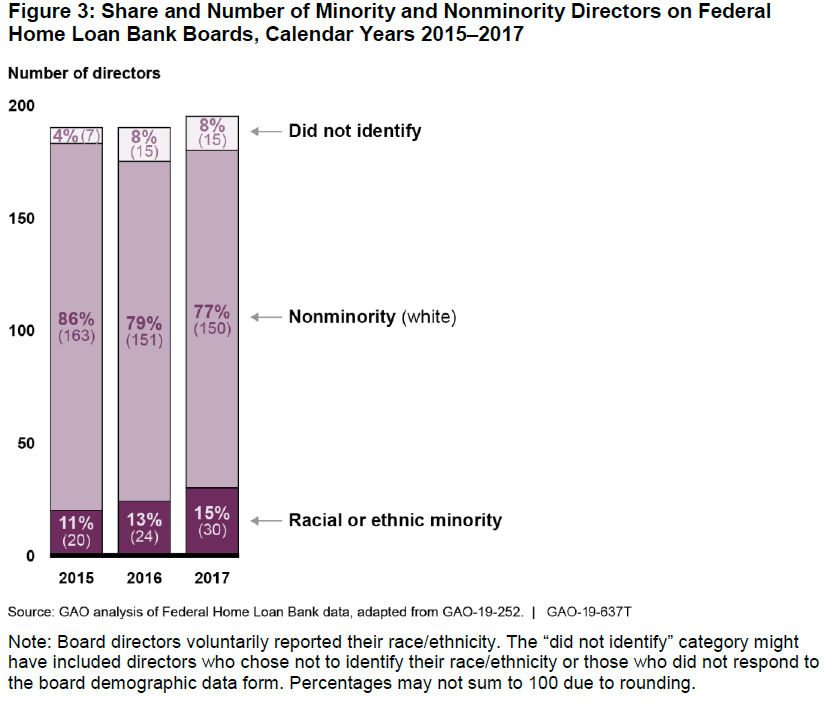

Our 2019 FHLBank board report also showed an increase in FHLBank directors from 2015 to 2017 for some minority groups, including African- American, Hispanic, and Asian, but they still reflected a small portion of these boards. Further, the size of the increases in minority directors on FHLBank boards was less clear than for women directors due to incomplete data on directors’ race and ethnicity (see fig. 3).

Various Factors May Hinder Board Diversity

In 2015 and 2019, we identified similar factors that contributed to lower numbers of women and minorities on corporate and FHLBank boards. Notably, stakeholders, board members, and others we interviewed said three key factors generally limited greater board diversity: (1) not prioritizing diversity in recruitment efforts, (2) limitations of the traditional board candidate pipeline, and (3) low turnover of board seats.

Not Prioritizing Diversity in Recruitment Efforts

In our reports on corporate and FHLBank board diversity, we found that not prioritizing diversity in recruiting efforts was contributing to a lack of women and minority candidates represented on these boards. For example, stakeholders told us board directors frequently relied on their personal networks to identify potential board candidates. Some stakeholders said that given most current board members are men, and peoples’ professional networks often resemble themselves, relying on their own networks is not likely to identify as many women board candidates. In our 2019 report on FHLBank board diversity, stakeholders we interviewed raised similar challenges to prioritizing diversity in recruitment efforts. Some FHLBank representatives said that member institutions—which nominate and/or vote on director candidates—may prioritize other considerations over diversity, such as a candidate’s name recognition.

Stakeholders we interviewed for our 2015 report suggested other recruitment challenges that may hinder women’s representation on corporate boards. For example, stakeholders said that boards need to prioritize diversity during the recruiting process because unconscious biases—attitudes and stereotypes that affect our actions and decisions in an unconscious manner—can limit diversity. One stakeholder observed that board directors may have a tendency to seek out individuals who look or sound like they do, further limiting board diversity. In addition, our 2015 report found some indication that board appointments of women slow down once one or two women are on a board. A few stakeholders expressed some concern over boards that might add a woman to appear as though they are interested in board diversity without really making diversity a priority, sometimes referred to as “tokenism.”

Limitations of the Traditional Board Candidate Pipeline

Our reports on corporate and FHLBank board diversity also identified challenges related to relying on traditional career pipelines to identify potential board candidates—pipelines in which women and minorities are also underrepresented. Our 2015 report found that boards often appoint current or former CEOs to board positions, [13] and that women held less than 5 percent of CEO positions in the S&P 1500 in 2014. [14] One CEO we interviewed said that as long as boards limit their searches for directors to women executives in the traditional pipeline, boards will have a difficult time finding women. Expanding board searches beyond the traditional sources, such as CEOs, could increase qualified candidates to include those in other senior level positions such as chief financial officers, or chief human resources officers.

In 2019 we reported that FHLBank board members said they also experienced challenges identifying diverse board candidates within the traditional CEO talent pipeline. Stakeholders we interviewed cited overall low levels of diversity in the financial services sector, for example, as a challenge to improving board diversity. Some bank representatives said the pipeline of eligible women and minority board candidates is small.

Several FHLBank directors said the requirements to identify candidates from within corresponding geographic areas may exacerbate challenges to finding diverse, qualified board candidates in certain areas of the country. By statute, candidates for a given FHLBank board must come from member institutions in the geographic area represented by the vacant board seat. Similarly, in 2011 we reported on Federal Reserve Bank directors and found they tended to be senior executives, a subset of management that is also less diverse. Our report also found that diversity varied among Federal Reserve districts, and candidates for specific board vacancies must reside in specific districts. [15]

Recruiting board candidates from within specific professional backgrounds or geographic regions is further compounded by competition for talented women and minority board candidates, according to some stakeholders. In 2019, board directors from several FHLBanks described this kind of competition. For example, a director from one bank said his board encouraged a woman to run for a director seat, but the candidate felt she could not because of her existing responsibilities on the boards of two publicly traded companies. We heard of similar competition among Federal Reserve Bank officials in 2011, where organizations were looking to diversify their boards but were competing with private corporations for the same small pipeline of qualified individuals.

Low Turnover of Board Seats Each Year

The relatively small number of board seats that become available each year also contributes to the slow increase in women’s and minorities’ representation on boards. Several stakeholders we interviewed for our 2015 report on corporate boards cited low board turnover, in large part due to the long tenure of most board directors, as a barrier to increasing women’s representation. In addition, with respect to FHLBank board diversity, Federal Housing Finance Agency staff acknowledged that low turnover and term lengths were challenges. Several stakeholders we interviewed for our 2019 report on FHLBank boards said balancing the need for board diversity with retaining institutional knowledge creates some challenges to increasing diversity. One director said new board directors face a steep learning curve, so it can take some time for board members to be most effective. As a result, the directors at some banks will recruit new directors only after allowing incumbent directors to reach their maximum terms, which can be several years. [16]

Potential Strategies for Increasing Board Diversity

Just as our 2015 and 2019 reports found similar challenges to increasing the number of women and minorities on corporate and FHLBank boards, they also describe similar strategies to increase board diversity.

While the stakeholders, researchers, and officials from organizations knowledgeable about corporate governance and FHLBank board diversity we interviewed generally agreed on the importance of diverse boards and many of the strategies to achieve diversity, many noted that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to increasing diversity on boards, and in some cases highlighted advantages and disadvantages of various strategies.

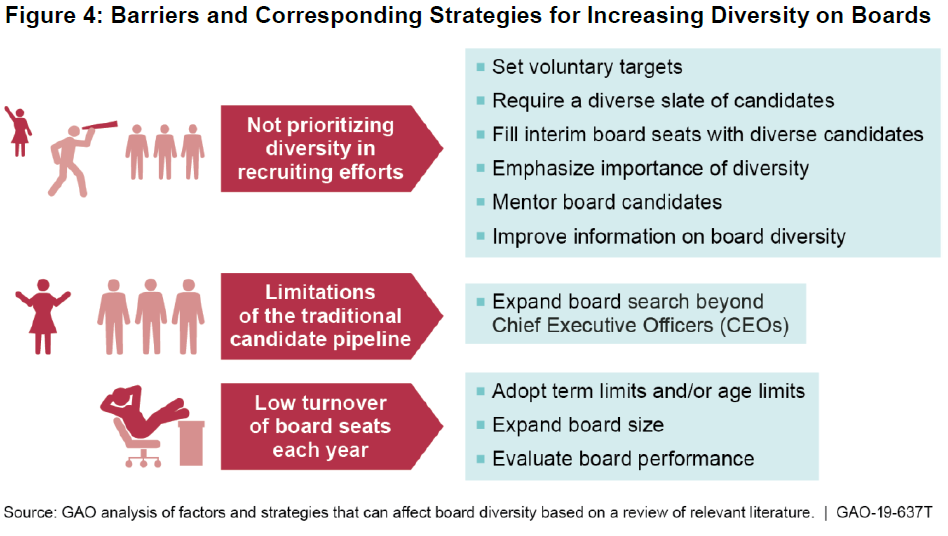

Based on the themes identified in our prior work, strategies for increasing board diversity generally fall into three main categories—making diversity a priority; enlarging the pipeline of potential candidates; and addressing the low rate of turnover (see fig. 4).

Making Diversity a Priority

Setting voluntary targets. Several strategies we identified in our 2015 report encouraged or incentivized boards to prioritize diversity. These strategies include setting voluntary targets for the number or proportion of women or minorities to have on the board. Many stakeholders we interviewed for our prior work supported boards setting voluntary targets for a specific number or percentage of women and minority candidates rather than externally imposed targets or quotas.

Requiring a diverse slate of candidates. Many stakeholders we interviewed supported a requirement by corporate boards that a slate of candidates be diverse. A couple stakeholders specifically suggested that boards should aim for slates that are half women and half men; two other stakeholders said boards should include more than one woman on a slate of candidates so as to avoid tokenism. Tokenism was also a concern for a few of the stakeholders who were not supportive of defining the composition of slates.

Filling interim board seats with women or minority candidates. Our 2019 report included strategies for making diversity a priority for FHLBank boards. For example, some FHLBank directors and Federal Housing Finance Agency staff said filling interim board seats with women and minority candidates could increase diversity. By regulation, when a FHLBank director leaves the board mid-term, the directors may elect a replacement for the remainder of his or her term. One director we interviewed said that when a woman or minority director fills an interim term, the likelihood increases that he or she will be elected by the member institutions for a subsequent full term.

Emphasizing the importance of diversity and diverse candidates. Our 2015 report found that emphasizing the importance of diversity and diverse candidates was important for promoting board diversity. Almost all of the stakeholders we interviewed indicated that CEOs or investors and shareholders play an important role in promoting diversity on corporate boards. For example, one stakeholder said CEOs can “set the tone at the top” by encouraging boards to prioritize diversity efforts and acknowledging the benefits of diversity. As we reported in 2019, FHLBanks have taken several steps to emphasize the importance of board diversity. For example, all 11 FHLBanks included statements in their 2017 election announcements that encouraged voting member institutions to consider diversity during the board election process. Six of the 11 banks expressly addressed gender, racial, and ethnic diversity in their announcements. In addition, we found that FHLBanks had developed and implemented strategies that target board diversity in general and member directors specifically. For example, the banks created a task force to develop recommendations for advancing board diversity and to enhance collaboration and information sharing across FHLBank boards. Each bank is represented on the task force. Directors we interviewed from all 11 FHLBanks said their banks conducted or planned to conduct diversity training for board directors, which included topics such as unconscious bias.

Mentoring women and minority board candidates. In addition, several stakeholders we interviewed about corporate and FHLBank boards noted the importance of CEOs serving as mentors for women and minority candidates and sponsoring them for board seats. For example, conducting mentoring and outreach was included as a strategy in our 2019 report for increasing diversity on FHLBank boards, including current directors pledging to identify and encourage potential women and minority candidates to run for the board. One director we interviewed said he personally contacted qualified diverse candidates and asked them to run. Another director emphasized the importance of outreach by member directors to member institutions to increase diversity on FHLBank boards. Member directors have the most interaction with the leadership of member institutions and can engage and educate them on the importance of nominating and electing diverse directors to FHLBank boards.

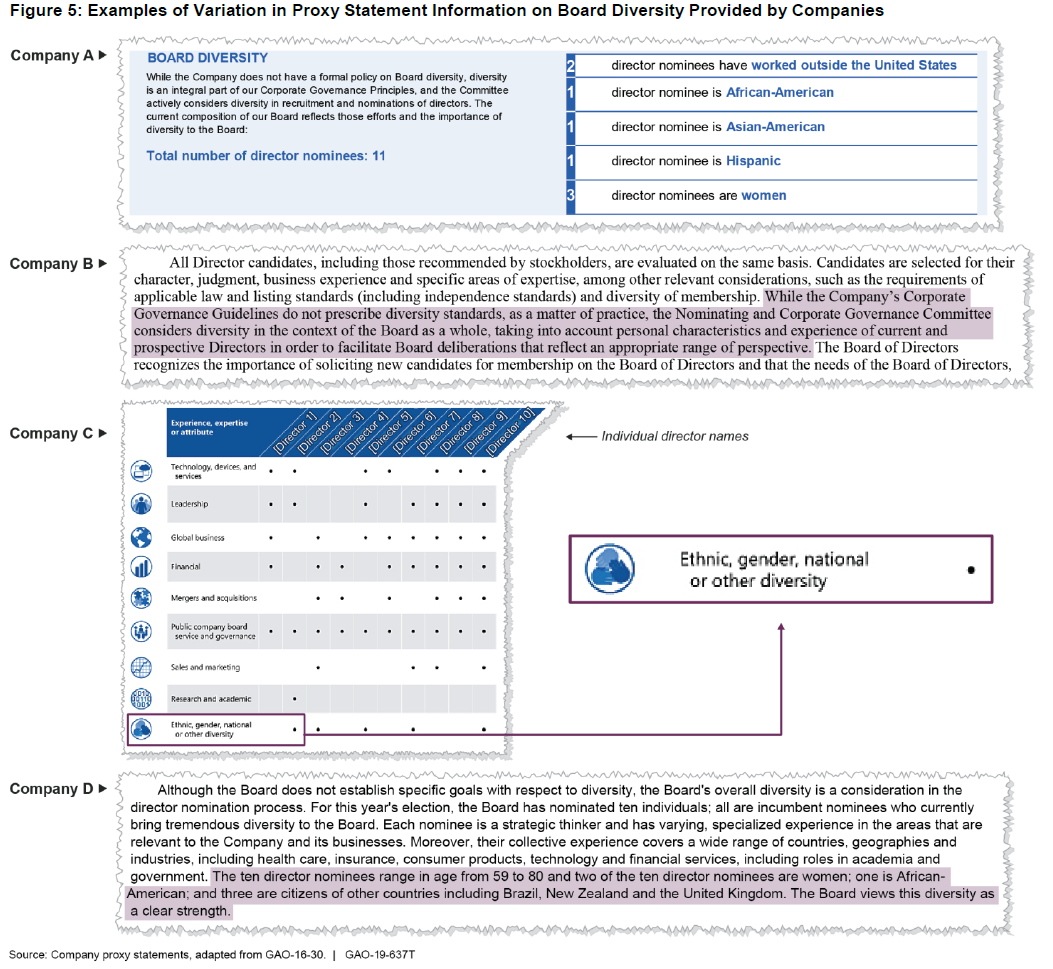

Improving information on board diversity. As we reported in 2015, several large investors and many stakeholders we interviewed supported improving federal disclosure requirements on board diversity. In addition to increasing transparency, some organization officials and researchers we interviewed said disclosing information on board diversity could cause companies to think about diversity more. While the SEC aims to ensure that companies provide material information to investors that they need to make informed investment and voting decisions, we found information companies disclose on board diversity is not always useful to investors who value this information. [17] SEC leaves it up to companies to define diversity. As a result, there is variation in how much and the type of information companies provide publicly. Some companies choose to define diversity as including characteristics such as relevant knowledge, skills, and experience. Others define diversity as including demographic characteristics such as gender, race, or ethnicity. [18] (See fig. 5) In February 2019, SEC issued new guidance on its diversity disclosure requirements, which aims to clarify the agency’s expectations for what information companies include in their disclosures. [19]

Nearly all of the stakeholders we interviewed for our 2015 report said investors also play an important role in promoting diversity on corporate boards. For example, almost all of the board directors and CEOs we interviewed said investors or shareholders can influence board diversity by exerting pressure on the companies they invest in to prioritize diversity when recruiting new directors. One board director we interviewed said boards listen to investors more than anyone else. For example, there have been recent news reports of investor groups voting against all candidates for board positions when the slate of candidates is not diverse.

In addition, in 2019 we recommended that the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which has regulatory authority over FHLBanks, review FHLBanks’ data collection processes for demographic information on their boards. [20] By obtaining a better understanding of the different processes FHLBanks use to collect board demographic data, the Federal Housing Finance Agency and the banks could better determine which processes or practices contribute to more complete data. More complete data could ultimately help increase transparency on board diversity and would allow them to effectively analyze data trends over time and demonstrate the banks’ efforts to maintain or increase board diversity.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency agreed with this recommendation and said it intends to engage with FHLBanks’ leadership to discuss board data collection issues. The agency also stated that it plans to request that the FHLBank Board Diversity Task Force explore the feasibility and practicability for FHLBanks to adopt processes that can lead to more complete data on board director demographics.

Enlarging the Pipeline of Potential Board Candidates

Expanding board searches beyond CEOs. Expanding searches for potential board members is yet another strategy for increasing board diversity, as we reported in 2015 and 2019. Almost all the stakeholders we interviewed supported expanding board searches beyond the traditional pipeline of CEO candidates to increase representation of women. Several stakeholders suggested that boards recruit high performing women in other senior-level positions or look to candidates in academia or the nonprofit and government sectors. Our 2015 analysis found that if boards expanded their director searches beyond CEOs to include senior-level managers, more women might be included in the candidate pool. Our 2019 report on FHLBank board diversity also included looking beyond CEOs as a strategy for increasing diversity. For example, we reported that FHLBanks can search for women and minority candidates by looking beyond member bank CEOs. By regulation, member directors can be any officer or director of a member institution, but there is a tendency to favor CEOs for board positions, according to board directors, representatives of corporate governance organizations, and academic researchers we interviewed for the report. Similar to the findings from our 2015 report, the 2019 report found that the likelihood of identifying a woman or minority candidate increases when member institutions look beyond CEOs to other officers, such as chief human resources officers. Several directors of FHLBanks also reported hiring a search firm or consultant to help them identify women and minority candidates, which is a strategy that can be used to enlarge the typical pool of applicants.

Addressing the Low Rate of Turnover

Adopting term limits or age limits. Several stakeholders discussed adopting term or age limits to address low turnover of board members. Most stakeholders we interviewed for our 2015 report were not in favor of adopting term limits or age limits, and several pointed out trade-offs. For example, one CEO we interviewed said directors with longer tenure often possess invaluable knowledge about a company that newer board directors do not have. Many of the stakeholders who opposed these strategies noted that term and age limits seem arbitrary and could result in the loss of high-performing directors.

Expanding board size. Several stakeholders we interviewed supported expanding board size either permanently or temporarily so as to include more women. Some stakeholders noted that expanding board size might make sense when a board is smaller, but expressed concern about challenges associated with managing large boards.

Evaluating board performance. Another strategy we identified in our 2015 report to potentially help address low board turnover and in turn increase board diversity was conducting board evaluations. Many stakeholders we interviewed generally agreed it is good practice to conduct evaluations of the full board or of individual directors, or to use a skills matrix to identify skills gaps. However, a few thought evaluation processes could be more robust. Others said that board dynamics and culture can make it difficult to use evaluations as a tool to increase turnover by removing under-performing directors from boards. Several stakeholders we interviewed discussed how it is important for boards to identify skills gaps and strategically address them when a board vacancy occurs, and one stakeholder said identifying such gaps could help boards think more proactively about finding diverse candidates. The National Association of Corporate Directors has encouraged boards to use evaluations not only as a tool for assessing board director performance, but also as a means to assess board composition and gaps in skill sets.

Chairwoman Waters, Ranking Member McHenry, and Members of the Committee, this completes my prepared statement. I would be pleased to respond to any questions that you may have at this time.

Endnotes

1GAO, Corporate Boards: Strategies to Address Representation of Women Include Federal Disclosure Requirements, GAO-16-30 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 3, 2015) and GAO, Federal Home Loan Banks: Steps Have Been Taken to Promote Board Diversity, but Challenges Remain, GAO-19-252 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 14, 2019).(go back)

2See, for example, GAO, Financial Services Industry: Representation of Minorities and Women in Management and Practices to Promote Diversity, 2007-2015, GAO-19-398T (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 27, 2019), GAO, Financial Services Industry: Trends in Management Representation of Minorities and Women and Diversity Practices, 2007- 2015, GAO-18-64 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 8, 2017), and GAO, Diversity in the Technology Sector: Federal Agencies Could Improve Oversight of Equal Employment Opportunity Requirements, GAO-18-69 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2017). See Enclosure I for additional related reports.(go back)

3GAO-16-30 and GAO-19-252.(go back)

4The S&P Composite 1500 combines three indices—the S&P 500, the S&P MidCap 400, and the S&P SmallCap 600. S&P 500 companies have an unadjusted market capitalization (the total dollar market value of all of a company’s outstanding shares) of $5.3 billion or greater; S&P MidCap 400 companies have an unadjusted market capitalization of $1.4 billion to $5.9 billion; and S&P SmallCap 600 companies have an unadjusted market capitalization of $400 million to $1.8 billion. In this report, we refer to these companies as large, medium, and small, respectively. Appendix I of GAO-16-30 contains more information about our analysis of S&P Composite 1500 companies.(go back)

5The 2011 report reviewed the governance of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks, each of which has a board of directors. See GAO, Federal Reserve Bank Governance: Opportunities Exist to Broaden Director Recruitment Efforts and Increase Transparency, GAO-12-18 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 19, 2011).(go back)

6A public company can be defined in various ways, but the SEC defines the term on its website to include companies that trade securities on public markets and disclose certain business and financial information regularly to the public.(go back)

7The requirements concerning corporate structure, including the role of boards of directors, are primarily determined by state We did not examine specific state law requirements concerning boards of directors.(go back)

8https://www.spencerstuart.com/-/media/2018/october/ssbi_2018_trends.pdf.(go back)

10For example, see Katherine Phillips, How Diversity Works, Scientific American, October 2014.(go back)

11For an overview of research on the impact of women on firm performance, see Gary Simpson, David A. Carter, and Frank D’Souza, “What Do We Know About Women on Boards?”, Journal of Applied Finance, No. 2 (2010); and Deborah L. Rhode and Amanda K. Packel, Diversity on Corporate Boards: How Much Difference Does Difference Make, 39 Del. J. Corp. L., 2 (2014).(go back)

12Appendix I of GAO-16-30 contains more information about this projection.(go back)

13Heidrick and Struggles, Board Monitor: Four Boardroom Trends to Watch, New York (2015). This report also found that current and former CEOs and chief financial officers together claimed two-thirds or more of new appointments to boards of Fortune 500 companies in 2014.(go back)

14This study also reported that 10 percent of chief financial officers in the S&P 1500 were women. EY Center for Board Matters, Women on US Boards: What are We Seeing? (2015).(go back)

15We recommended in GAO-12-18 that Reserve Banks consider ways to broaden their pipeline of potential candidates for directors, such as including officers who are below the senior executive level at their organizations, among other recommendations. We closed the recommendation based on a 2011 memorandum sent by the Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve Board to all Reserve Bank presidents encouraging consideration of potential candidates who hold positions below the senior executive level in their organizations. The Vice Chair’s annual letter to Reserve Bank leadership also emphasized the Board’s focus on increasing director diversity.(go back)

16Under FHLBank board statutory requirements, as amended by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, directors generally serve 4-year terms. Typically, directors cannot be elected to serve more than three consecutive full terms, totaling 12 years. A director may be reelected to a directorship for a term that commences no earlier than 2 years after the expiration of the third full term.(go back)

17According to SEC, information is considered material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important in making an investment or voting decision. The standard for materiality has been established by case law, including TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc., 426 U.S. 438 (1976).(go back)

18Aaron Dhir, Challenging Boardroom Homogeneity: Corporate Law, Governance, and Diversity (Cambridge University Press, April 2015).(go back)

19For the guidance, see https://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/regs-kinterp.htm#116-11 and https://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/regs-kinterp.htm#133-13.(go back)

20As of June 2019, this recommendation was open. The Federal Housing Finance Agency’s 2015 regulation amendments require FHLBanks to compare board demographic data with prior year’s data and provide a narrative of the analysis. The Federal Housing Finance Agency also stated in the amendments that it intended to use the director data to establish a baseline to analyze future trends of board diversity.(go back)

Print

Print