Ric Marshall is Executive Director of ESG Research at MSCI Inc. This post is based on his MSCI memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Untenable Case for Perpetual Dual-Class Stock (discussed on the Forum here), and The Perils of Small-Minority Controllers (discussed on the Forum here), both by Lucian Bebchuk and Kobi Kastiel, and the keynote presentation on The Lifecycle Theory of Dual-Class Structures.

Two companies, one highly disruptive business model, multiple big challenges looming. Few IPOs in recent memory have attracted more attention—or disappointed more decisively, initially—than the IPOs of ride-sharing groups Uber and Lyft. At the end of June 7, 2019, two months following its IPO, Lyft’s share price traded at 17.7% below its IPO price, while Uber’s ended that same day 1.9% lower. Could ESG considerations have played into investors’ thinking?

Both companies demonstrate striking similarities. Not only do they compete directly with each other, both are investing in autonomous vehicles. Both have large off-the-books workforces as their drivers are classified as independent contractors rather than employees. And both must protect their passengers—both physically and digitally given the amount of personal data they possess. All of these are major issues that have the potential to threaten their business models in the face of regulatory change or consumer backlash.

But one area where their paths have differed markedly, which might have an outsize importance to investors: their listed ownership structure, more specifically around the key question of ownership control alignment, or ownership control skew. [1] Why does this matter? In Uber’s case, investors’ level of influence over the company is commensurate with how many shares they own, while in Lyft’s, investors have virtually no influence, regardless of how many shares they own.

Why should investors care?

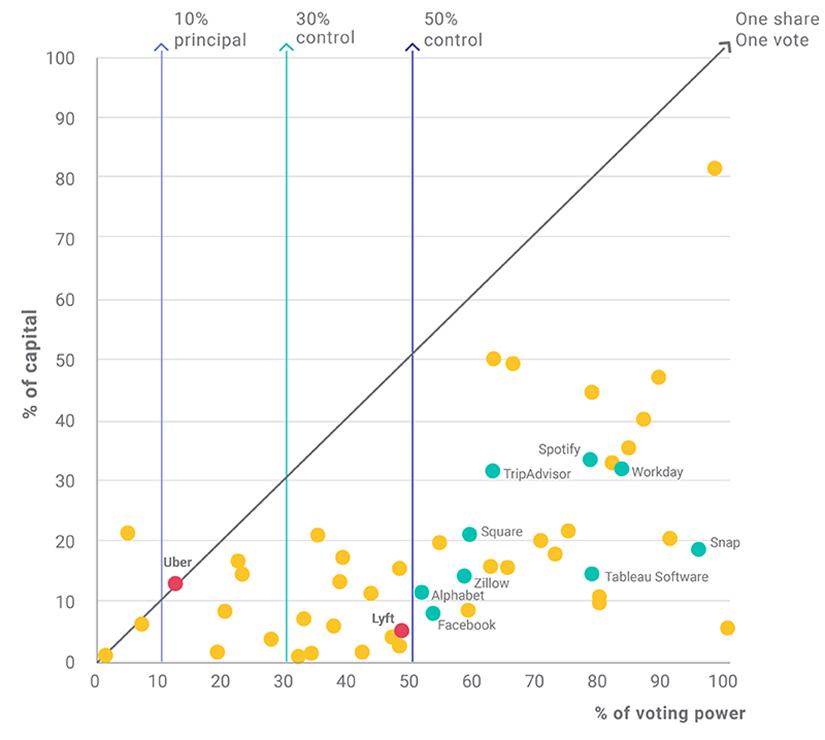

Unlike Lyft, where the company’s founders retained the ability to assert control over the company’s future, Uber listed its shares in compliance with the one-share, one-vote rule, which ensures that the economic interests and voting power of all investors are perfectly aligned, as illustrated in the exhibit below. At Uber, unlike Lyft—where Class A shares represent just 52% of the total voting rights, even though investors in these provided over 95% of the total raised capital [2]— all investors will have an equal say in the company’s affairs, commensurate with their level of investment.

Ownership control alignment at Uber and Lyft

The chart plots the percentages of capital and voting rights held by the largest owner or owner group of Uber and Lyft, respectively, compared to other U.S. companies that employ multiple share classes.

Source: MSCI ESG Research, as of May 31, 2019. Uber plotted with 50 constituents of the MSCI USA Index with multiple share classes with unequal voting rights, plus non-constituents Spotify and Snap for recent comparisons. Information on Uber’s share structure found in Uber Technologies, Inc. prospectus. Information on Lyft’s share structure found in Lyft Inc. Amendment No. 2 to Form S-1 Registration Statement.

While Lyft went public as a controlled company, Uber’s shares, by contrast, were listed as widely held stock. Its founders serve as Uber directors but no longer actively manage the company, and are no longer in a position of control. Admittedly, Uber’s executives and directors as a group continue to hold in excess of 26% of the company’s shares, according to the company’s prospectus, and both of Uber’s founders retained a sizeable number of shares—4.6% of Uber’s voting shares in the case of Garrett Camp, and 6.7% in the case of Travis Kalanick. But while their continued influence is likely, their influence will be proportionate to their economic interest.

Influence is very different from control

There are pros and cons to each approach to ownership; neither has been proven to be consistently better or worse than the other. In our experience, controlled companies have tended to be more decisive and quicker to act. They have also shown greater potential for both over- and under-performance, relative to their principal or widely held peers.

Risk and return at controlled vs. widely held shares or principal firms

| Controlled | Widely held |

|---|---|

| Less risk adverse | More risk adverse |

| More decisive | Slower to act |

| Potential outperformance | Lower risk |

Source: MSCI ESG Research

Founder control is not the only concern expressed by investors in these two companies. It may not even be the most compelling. No one can predict whether or to what extent the differences in ownership and control structures at these two companies will play in determining their future, but it’s a difference that investors may want to consider. As a widely held company, where the economic interests and voting rights of all investors are perfectly aligned, Uber presents a distinctly different investment opportunity than founder-controlled Lyft, whose dual-listed shares and disparate voting rights severely limit the influence of minority investors.

Endnotes

1Brett, A. 2019. “Assessing Control: Measuring and Assessing the Alignment Between Economic Exposure and Voting Power at Controlled Companies.” MSCI ESG Research.(go back)

2Brett, A.; Moscardi, M. 2019. “Need a Lyft? Why the IPO blew a tire.” MSCI Blog.(go back)

Print

Print