Stilpon Nestor is Managing Director and Konstantina Tsilipira is an Analyst at Nestor Advisors Ltd. This post is based on their Nestor Advisors report.

Introduction

This post is based on research carried out for a European client bank. It is about board governance in large banking organisations. Using information from a sample of 32 international “best practice” banks compiled by Aktis Ltd (www.aktisintel.com) and a series of interviews with bank board leaders and senior supervisors, we examine the way bank boards organise themselves to effectively deliver their tasks: directing and controlling the organisations they lead; and taking timely, effective decisions in this regard.

The complete publication develops along three broad themes: board leadership, board interface with management and board—level strategic human resources issues. This post focuses on four specific areas within these broad themes: board composition, i.e. the profile of the people that populate the boards of best practice banks; board succession planning and nomination approaches which will determine the quality of people over time and ensure continuity; board committees, i.e. the way the board organises itself to manage areas where conflicts might arise and/or where expertise and deep dives are required; and senior management committee architecture, which reflects the changing strategic priorities and risk perspectives of major banks, determines the sources of board information and orders accountability of management to the board.

We recognise that best practice in the areas under investigation comes in many forms. Differences are due not only to jurisdictional idiosyncrasies but also to different philosophies, corporate origins and legacy. While common solutions do exist, very often we find that there is more than one way to address board governance imperatives.

Board composition

In the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis, banks saw a tsunami of board related regulation. In addition to specific processes prescribed for the “maintenance” of adequate knowledge, skills and experience (“KSE”) among board members, supervisors now expect specific skills for key board positions. Candidates for these positions are vetted and their competences are regularly reviewed in the context of supervisory reviews.

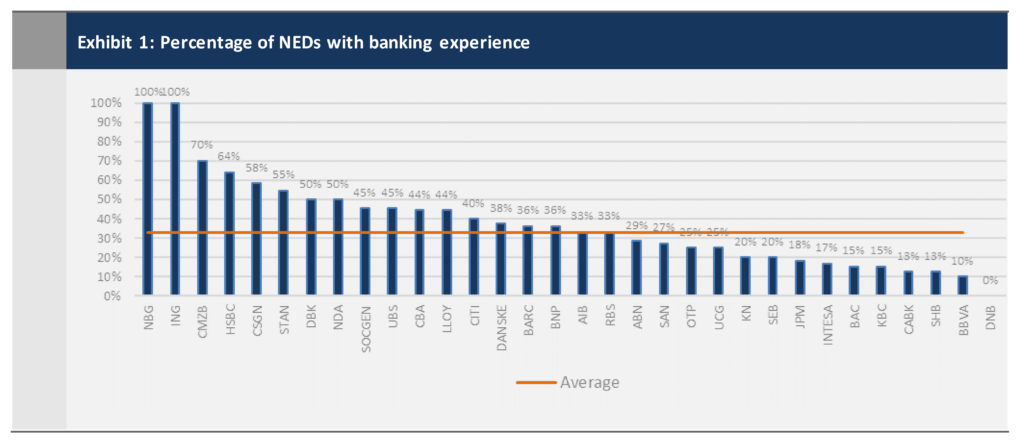

So, what skills are needed on a bank board? In line with the widely-held consensus that directors’ lack of banking expertise was a key contributor to the crisis, the 2009 Walker Review recommended that “a majority of NEDs should be expected to bring to the board materially relevant financial experience […]”. However, the Review also notes that “there will still be scope and need for diversity in skillsets and different types of skillset and experience”. The European Commission (2010) reinforced this point, highlighting that, before the crisis, “members of boards of directors did not come from sufficiently diverse backgrounds”.

Banking experience on boards, although necessary, is not enough. Leading bank boards frequently include members who bring something other than banking knowledge. For instance, while about 45% of SOCGEN non-executive directors (“NEDs”) possess some banking experience (as per Exhibit 1), a broad array of non-banking complementary skills is also present on the board: there are four NEDs with non-banking financial services experience (e.g. the founder of an asset manager), four NEDs with marketing and customer services experience (e.g. the CEO of an online creative platform for entrepreneurs), and three NEDs with industry background (e.g. the chair of an aerospace, transport and infrastructure company). At BARC, where 36% of NEDs have banking experience, ten out of twelve NEDs also have experience in financial services other than banking while some NEDs bring experience from the regulatory policy area (e.g. former senior executives in the UK Treasury and the Prime Minister’s Office). The NDA board, where half of NEDs are former bankers, comprises four NEDs with non-banking financial services backgrounds (including a global head of an insurance holding), two NEDs with IT and digital expertise (e.g. the managing director of a technology investment company), one NED with significant legal experience (the chief legal officer of a multi-national), and one NED with industry background (the managing director of an oil company). Finally, at JPM, one of the most successful banks in the world, only 18% of the NEDs have banking experience; almost half of NEDs are non-financial industry leaders. This is quite representative of the US approach: bank boards have much lower levels of banking expertise and their supervisors seem to be more accommodating on this point than their European counterparts.

They might be right: an appropriate mix of professional backgrounds and profiles enable boards to consider strategic matters from various angles—including the angle of clients; to think out-of-the-box; and to avoid groupthink. In other words, diversity is good—not only gender but also skillset and cultural diversity.

But there might be too much of a good thing. Boards sometimes risk becoming congregations of specialists and experts who can perform very well in certain narrow areas, but sometimes do not have the broader capacity to “see the forest”. But most banks seem to have a preference for “all-rounders”, sacrificing specific expertise (e.g. cyber risk, other risk management skills etc) for broader leadership experience. The two approaches can be—and are often—mutually compatible. But there is always tension at the margin.

NBG and ING are the only banks in the peer group with a board composed entirely of members with direct banking experience (Exhibit 1). The average percentage of NEDs with banking expertise among the peers is 35%, a number that allows for a degree of balance between industry expertise and diversity of professional backgrounds.

In addition to banking expertise, other skills and backgrounds beyond banking are common among NEDs in bank boards.

Profiles of board chairs

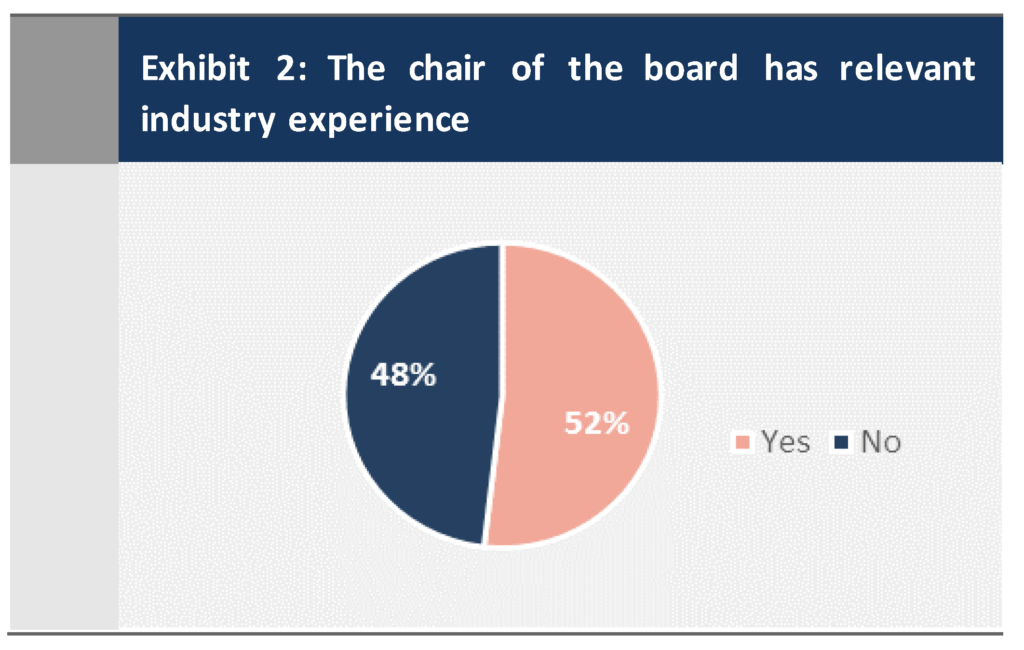

The chair of the board plays a crucial role in the quality of its composition and deliberations. He/she provides leadership and ensures effectiveness in the way the board discharges its responsibilities. Chairs need to possess special experience and have specific skills and competences. However, they need not necessarily be bankers.

Exhibit 2 shows that only in about half of the banks in the peer group does the chair have significant banking expertise (i.e. having previously worked in the banking industry).

Board chairs within the peer group show a variety of skills beyond banking. At LLOY, for example, the chair of the board possesses experience in the insurance industry, regulatory and public policy, property investment and development, technology and environmental analysis, strategy consulting and senior civil service. Similarly, the INTESA chair possesses a diversified skill profile including experience in the oil & gas and automotive industries, insurance, academia and economic research.

It is interesting to note that many chairmen of UK banks do not have banking expertise, in spite of the UK’s Senior Managers and Certification Regime (“SMCR”) which assigned specific responsibilities (and liability) to chairs. Even this strictest of regimes as regards individual accountability does not consider banking expertise to be a prerequisite of good chairmanship.

International background among NEDs

Directors who are not nationals of the bank’s country of origin might be agents of cultural diversity.

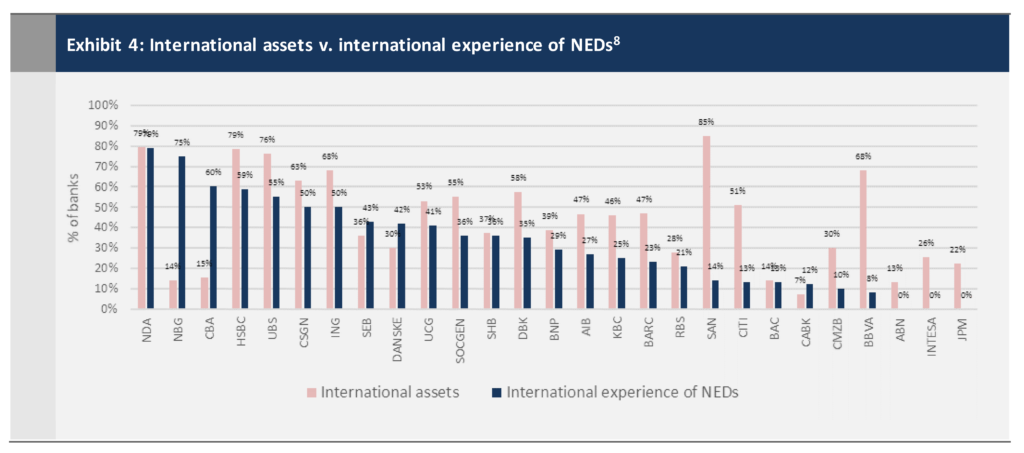

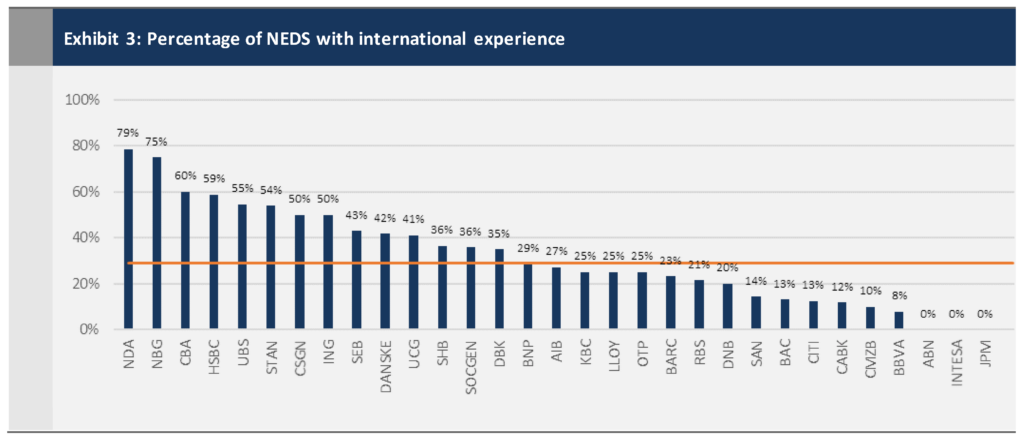

As per Exhibit 3, the norm is that “local” directors predominate. This is especially the case in banks whose business is primarily local. Most banks with international revenues of less than 40% (such as ABN, BNP, CMZB, DANSKE, INTESA and JPM) have few “international” directors.

International directors fill on average a third of board seats and are mostly present in banks with significant revenues outside their domestic market (Exhibit 4). Board composition in two banks is counterintuitive in this respect: At SAN, only 14% of NEDs have international experience despite 85% of their assets being non-domestic; NBG and CBA are exactly the opposite i.e. there is a high percentage of international NED experience (75%) despite a low proportion of international assets (14%).

International directors fill on average a third of board seats and are mostly present in banks with significant revenues outside their domestic market (Exhibit 4). Board composition in two banks is counterintuitive in this respect: At SAN, only 14% of NEDs have international experience despite 85% of their assets being non-domestic; NBG and CBA are exactly the opposite i.e. there is a high percentage of international NED experience (75%) despite a low proportion of international assets (14%).

The presence of international directors is limited and roughly proportionate to the international exposure of the relevant bank.

Presence of executive directors on the board

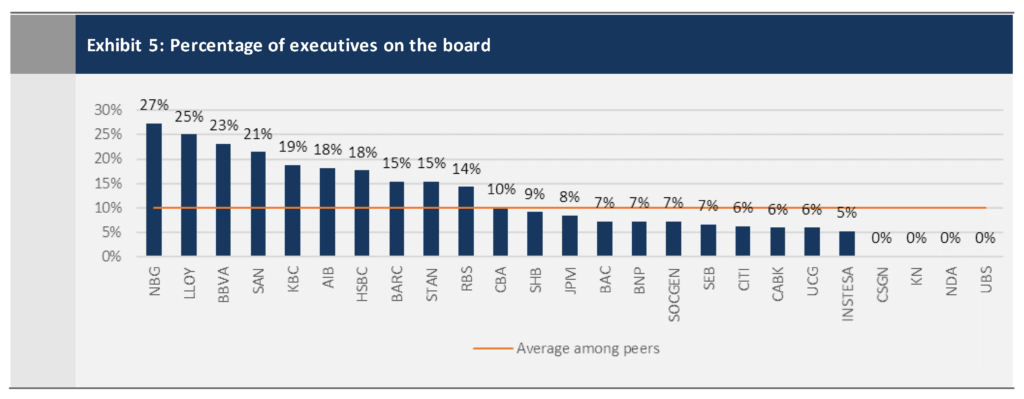

The presence of executive directors on unitary banking boards has been diminishing over time—a trend mostly driven by supervisors. Currently, most unitary boards include few executive directors on the board. It did not use to be that way. The first UK Corporate Governance Code argued for a “significant minority” of executive directors. Maybe that is why most UK banks still have an above average executive presence on their boards. But over the last 15 years, there has been a general trend in the banking sector of fewer and fewer executive directors—including in the UK. As Exhibit 5 suggests, only 4 bank boards had more than 20% of their boards composed of executive directors in 2018.

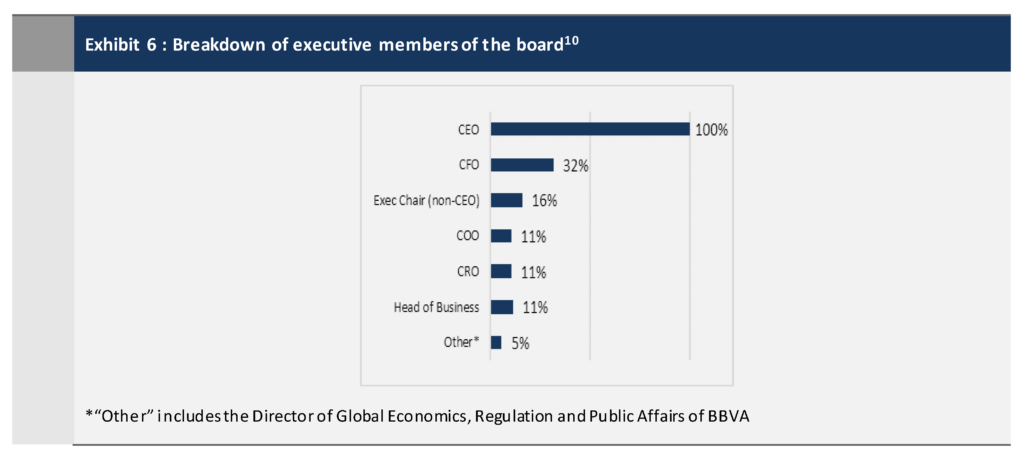

The inclusion of executives on the board is usually underpinned by a specific rationale: a director’s position should be important enough to the business for him/her to have a voting seat at the top table and, more importantly, to be directly accountable to the shareholders. The requisite weight is functional rather than personal, i.e. rarely one sees executives on boards regardless of their position in the bank.

This approach works well if there is a certain degree of collegiality in the way the executive committee works; if not, the presence of several executives might be somehow ineffectual as they might refrain from offering their personal perspective and prefer to “stick to the party line”. But there is an alternative approach that we could call the “Spanish”. It goes “hand-in-hand” with the executive leadership being split between a CEO and an executive chair. In this world, the executive directors (other than the executive chairman) are not functional or business leaders within the firm but, rather, senior overseers with broad mandates. They are appointed as experienced persons rather than function holders—much like NEDs. For example, in the old SAN board, there was an executive director overseeing strategy while another was overseeing risk. Both were old SAN “hands”, but neither was the head of the respective executive function. They were there to support the chairman, not the CEO. Similarly, the current BBVA board includes, in addition to the deputy chair, a senior former central banker with a broad, “roaming” oversight brief over regulatory and strategic matters.

As one would expect, banks with executives on their boards always include the CEO (Exhibit 6). CFOs are the second function more often represented at board level since the integrity of reporting and adequacy of capital management are a key concern of bank shareholders—and supervisors. COOs are a relatively recent arrival on boards and are usually there to emphasize the importance of IT/cyber risk. CROs are also a recent addition, while the traditionally significant presence of heads of businesses has been recently receding.

LLOY, a bank with relatively high “executive content”, has three executives on its board: the CEO, CFO and COO. BBVA has a more intriguing balance: it includes an executive chair (like its compatriot, SAN) and a former central banker with broader regulatory and broader economic policy responsibility.

There is limited and diminishing presence of executive directors on boards.

Board committee composition and leadership

Boards have committees for three essential reasons: to allow for in-depth examination and understanding of certain key matters among the board’s significant responsibilities; to hold management for the above areas accountable in a more systematic way; and to segregate the discussion of matters in which conflicts might arise among different categories of board members, i.e. independent NEDS (“iNEDS”) vs. executive directors vs. other non-independent NEDs (e.g. major shareholder representatives, significant clients etc.). These three reasons drive choices on the profile of committee members in terms of independence, skills, knowledge and experience.

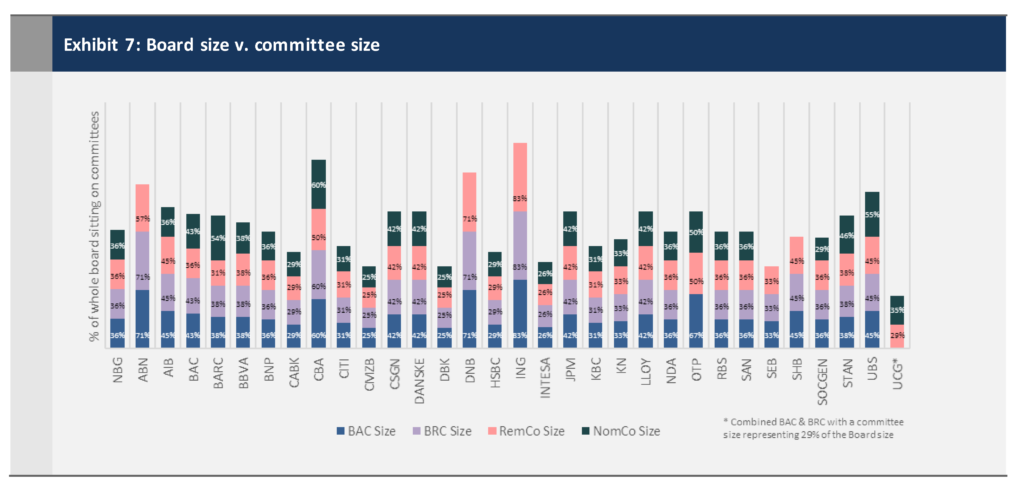

As Exhibit 7 shows, most banks tend to distribute members across the main committees relatively evenly. The Board Risk Committee (“BRC”) and the Board Nomination Committee (“NomCo”) tend to be slightly more populous—5 members on average—relative to the Board Audit Committee (“BAC”) and the Board Remuneration Committee (“RemCo”) whose average size is 4.

Furthermore, across banks in our peer group, the median number of committee memberships per NED is 2 with the maximum number being 3.1 and the minimum 1. Most board committees in our peer group employ a relatively limited subset of the board. One rarely sees anymore the “old Goldman approach” of all NEDs sitting in all committees—although the Dutch banks show significant overlaps in committee membership. In at least one peer bank all NEDs attend all committee meetings as observers which has largely the same practical results as “old Goldman”. However, EBA appears to discourage such full overlap.

“Old Goldman” practices are looked down upon by European supervisors for reasons of board dynamics and probity: they make for a crowded room, might be problematic for conducting in-depth discussions, and might create obstacles to the probing of sensitive issues. At a more general level, supervisors in Europe expect two layers of challenge: one at committee and one at board level. If all directors attend all committee meetings, the second layer of challenge is lost, and the board discussion essentially becomes a brief, rubber-stamping exercise.

Some banks explicitly rotate membership in committees, a practice that is in line with the EBA Guidelines on Internal Governance (the “EBA Guidelines”) according to which “institutions should consider the occasional rotation of chairs and members of the committees, taking into account the specific experience, knowledge and skills that are individually or collectively required for those committees”.

The distribution of members across board committees is roughly even, while individual NED membership / attendance in all board committees is nowadays rare.

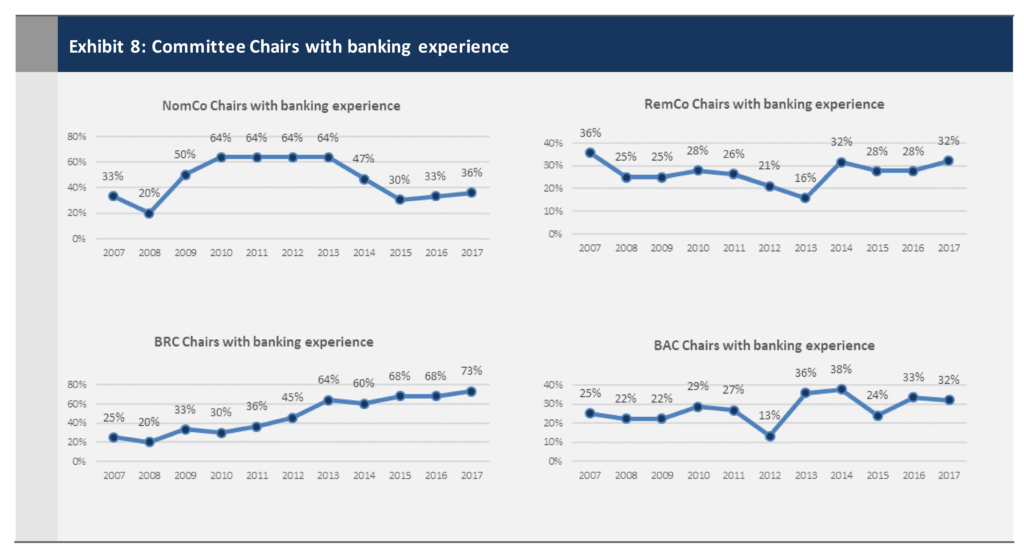

As regards skills required in specific committees, the EBA Guidelines provide that “members of the BRC should have, individually and collectively, appropriate knowledge, skills and experience concerning risk management and control practices” while Directive 2006/43/EC stipulates that “At least one member of the BAC … shall have competence in accounting and/or auditing”.

Most boards assign to their governance and nomination committee the distribution of member skills across committees. One interviewee noted that “our NomCo spends a significant amount of its time [it meets four times/year] matching committee membership with skills.” Also, our experience suggests that candidates for the board are usually selected with an eye on their future committee contributions. The role of committee chairs is key, especially since they are usually expected to spend significant time in understanding the aspects of the firm’s activities that they oversee and in holding executives assigned to them accountable. Under the UK’s Senior Managers Regime, the chairs of the four main committees are held directly accountable for the effectiveness of their respective committees.

Exhibit 8 suggests that most committee chairs are not necessarily banking experts, with the significant exception of the BRC where banking expertise for the chair is the norm, at 73%. This has grown from 25% in the decade since the crisis!

As regards other skills, BAC chairs generally are “financial experts” as per the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) definition which may derive from being a former auditor or the CFO of a large corporation. RemCo chairs in best practice banks are, more often than not, senior executives in various industries (but rarely in the financial sector, for conflict reasons). And, as discussed below, NomCos are often chaired by the chair of the board.

Board chairs chair or are a member of the NomCo in most cases.

Board-level nomination and succession planning

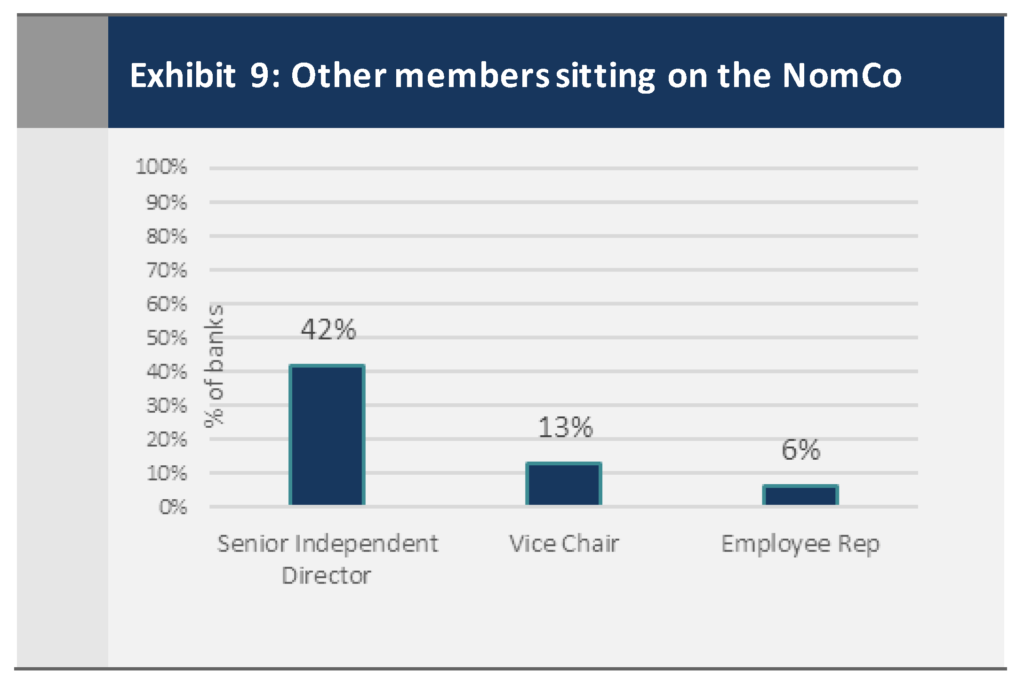

The NomCo’s main role is to follow board composition and plan director succession. In most jurisdictions (including the Eurosystem, the US and Australia), this is a key board responsibility given its significant impact on performance: it is rare, over time, that an incompetent board might oversee a performing firm. While shareholders eventually approve and can influence composition, the initiative is with the board.

The chairman has primary responsibility for the effectiveness of the board which, in its turn, is linked to the quality of the people who compose it. It is therefore not a surprise that, in 61% of the peers, the chair of the board is a member of the NomCo; and in 73% of the cases where the chair is a NomCo member, the chair also chairs the NomCo. It should be noted that in some of the banks where the board chair is not a member of the NomCo, this is because he is also the CEO of the bank, e.g. BAC and JPM.

Handing the initiative of member selection to the people that know the needs of the board best (i.e. the NomCo) makes a lot of sense. But it is also true that this is essentially a system of co-option that might constrain shareholders in their choice of candidate for the board, especially if the board / committee only uses its personal network for selecting candidates and does not expand the search using professional help.

Assigning to the board the responsibility for board composition is not a universal norm. In Sweden and Norway, it is the major shareholders that assume direct responsibility for board composition. They do consult with the board chair (and, sometimes, the CEO) but in general keep the nomination process away from the board. This is a system that could work well under certain conditions. It requires a few competent shareholders with large enough stakes to “care” about individual appointments; and shareholder organisations with adequate competences that allow them to manage the selection and nomination processes. In the absence of such “Wallenberg” (or similar, private equity-like) institutions, the system would be much less effective and would also raise supervisory questions as to its integrity.

In Germany, employees (who by law occupy half of supervisory board seats) sit in the NomCo. For instance, the NomCo of CMZB is made up of the chair of the Supervisory Board, two employees and two shareholder representatives.

Among NEDs, other members that normally sit on the NomCo include the Senior Independent Director or, alternatively, the independent Vice Chair (Exhibit 9). Their presence reflects the need to ensure the effectiveness of the chairmanship and the chair succession plan.

In practice, the chair is involved in director nomination in all peer banks. In the UK, he/she clearly leads the process, being in most cases the chair of the NomCo. But even when this might not be the case, he/she acts in conjunction with the NomCo chair in the initiation and conclusion of the selection process. According to one interviewee, the NomCo reviews the résumés of candidates and agrees on a shortlist of two or three people. Subsequently, the whole committee, including the chair of the board, interviews the shortlisted candidates on a one-on-one basis. Another interviewee presented an alternative in which the chair interviews all the shortlisted candidates while the NomCo meets only with the final candidate.

In most of the banks, the CEO attends most NomCo meetings and provides committee members with his/her views on NED succession—but also on other important matters such as appointments in subsidiary boards that typically come under the mandate of the committee. For example, CSGN, UBS, CMZB and UCG all disclose that the CEO is a permanent invitee to their NomCos. One interviewee noted that the CEO is expressly requested to provide his views on the NED nominee short list.

However, some banks do not involve the CEO in the nomination process. One interviewee has told us that he is rarely invited at the NomCo.

NomCos show differing levels of involvement in the selection of NED candidates but CEO views are almost always sought.

Most large banks use recruitment consultants as a primary interface with actual and potential candidates in order to ensure an objective, well-considered nomination process. Most interviewees noted that their boards always hire consultants to support the NED nomination process. The NomCo typically invites such consultants to present a long list of candidates out of which the committee selects the short list.

Even when candidates are sourced by alternative means—usually, informal networks—they typically would still go through the vetting process managed by board consultants. In this respect, it is important that the consultant’s incentives, approved by the NomCo, are conducive to promoting capable candidates who might not have been sourced by them.

Most leading banks use external recruitment consultancies as an interface with the market and individual candidates., irrespective of the sourcing of such candidates.

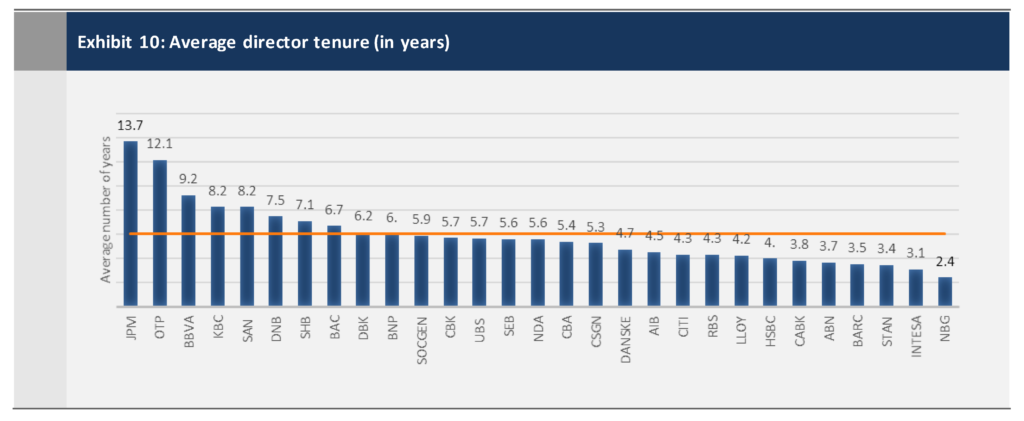

Board succession planning is intimately linked to the tenure of individual directors. Exhibit 10 shows a relatively wide span of average tenure amongst peer banks, averaging 5.7 years.

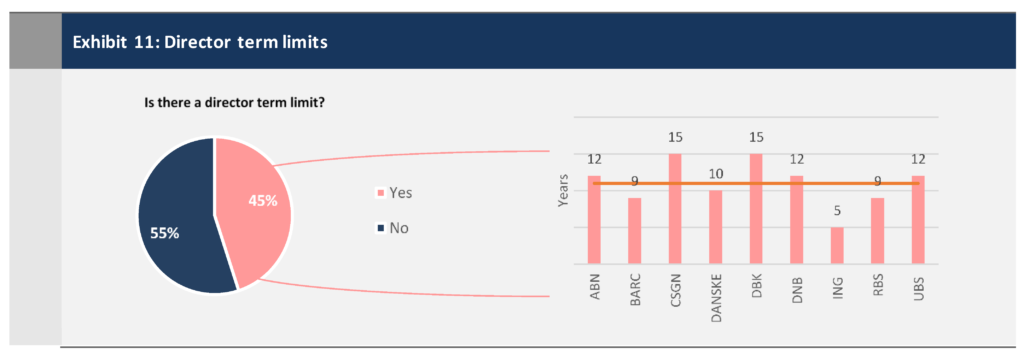

There are three related types of rules that affect the tenure of the board. The first refers to the maximum time a director may sit on a board. The second is about gradual succession, in order to achieve a proper mix of continuity and institutional memory with fresh perspectives on the business. The third one concerns the relative power of shareholders to determine board composition.

Companies may set term limits, a practice that is used more in Europe and less in the US. According to the 2018 United States Spencer Stuart Board Index, only 25 S&P 500 boards (5%) set explicit term limits for NEDs; they range from 9 to 20 years. A majority of existing US policies set term limits at 15 years or more. It is also worth noting that the average tenure of S&P 500 iNEDs is 8.1 years, longer than average tenure in most European listed companies.

In contrast, several European banks set director term limits (Exhibit 11). Towards the lower end of the spectrum, ING sets the limit at 5 years; at the higher end of the spectrum, banks such as CSGN, DBK and ABN have limits set at 12-15 years.

The underlying reason for setting a term limit is to encourage board refreshment and the entry of “new blood” on the board that might bring fresh, out-of-the-box perspectives. There is also a softer way of encouraging refreshment: setting a limit above which directors are no longer considered independent. Indeed, best practice Codes consider that a director loses his/her independence if he/she has served on a board for too long a period. The European Commission recommends that independent directors serve a maximum of three terms or twelve years. In the UK, the UK Corporate Governance Code provides that a board should explain, in its annual report, its reasons for determining that a director who has served more than nine years qualifies as independent.

Investors are now quite alert at such board “refreshment” issues and expect explanations by companies that consider independent directors who have stayed on their board too long.

Turning to the second issue, the interests of a bank are likely to be well served by having directors of varying longevity. The presence of “old hands” allows for deeper understanding of the organisation and its business; new arrivals bring with them fresh ideas and perspectives.

In most banks, this tenure mix is achieved through the development of a nomination practice that aims at the constant renewal of the board, founded on a nomination policy that enshrines refreshment as an imperative.

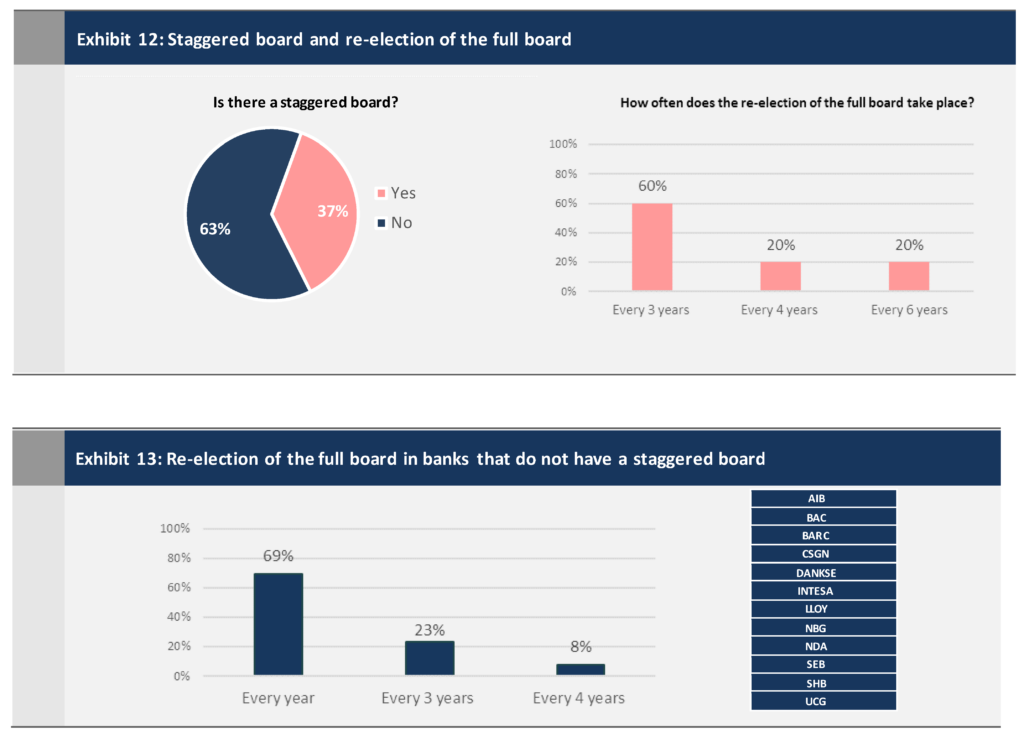

Staggering board appointments is a way to hard-wire a balance of “freshness” and experience. It is organised so that groups of roughly equal numbers of directors come up for election on different years.

Across our peer group, 37% have a staggered board (Exhibit 12). The majority (60%) of peer group banks with staggered boards re-elect the full board every 3 years. Other peers do so every 4 years (20%) or every 6 years (20%). It is important to note that in some jurisdictions (i.e. the US) staggering is primarily viewed as an anti-takeover (“poison pill”) device.

Turning to shareholder say, Exhibit 13 suggests that a majority of banks put their board up for shareholder “validation” through an AGM election every year, even if the “real” tenure cycle might be longer, driven by either hard or soft term limits. Shareholder annual votes are a relatively recent development originating in the UK and Switzerland. The purpose is to give a chance to the shareholders to express their dissatisfaction with specific directors on the board. It has rarely resulted in unexpected “firings”, but it does give an important signal to NomCos so that they may act in subsequent years.

NED board tenure varies but a majority of banks have developed some form of board refreshment mechanism. Most peer banks allow their shareholders an annual opportunity to validate the composition of the board.

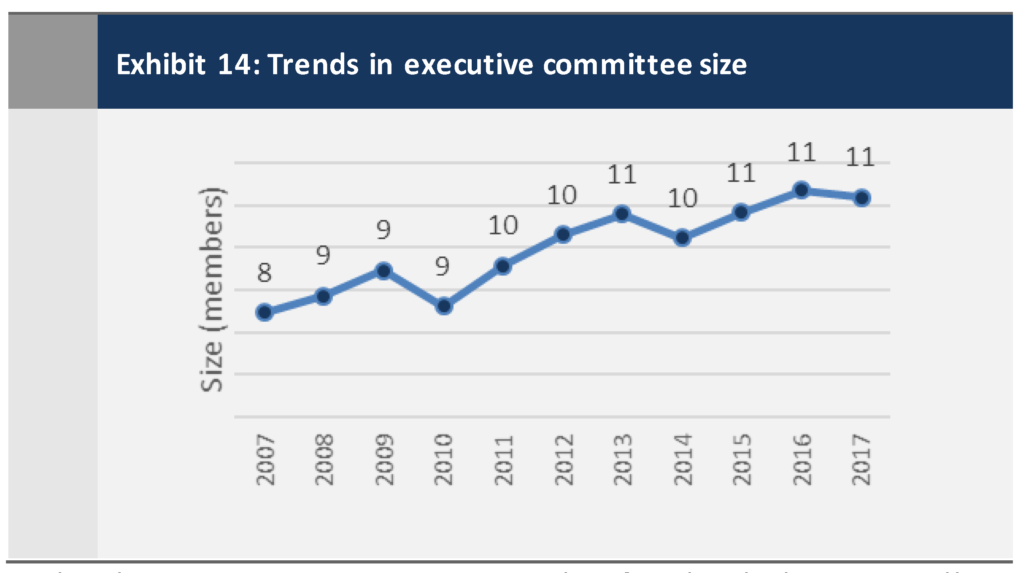

The executive committee usually sits at the top of the management committee structure. A plurality of one-tier peer group companies (44%) have executive committees numbering between 11 and 15 members. 37% are larger than 15 while 19% have fewer members. Only SOCGEN across our peer group has an executive committee (“General Management”) smaller than 6 members. In general, executive committees have grown larger over the last decade (See Exhibit 14).

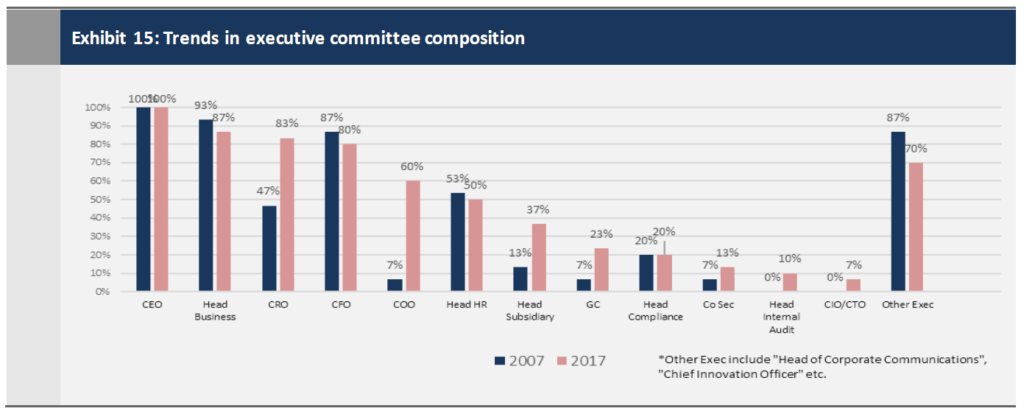

Similarly, the composition of the executive committee has changed significantly in certain aspects. The prime beneficiaries of this change have been “second line” control functions. Whereas the CEO, CFO and Heads of Businesses have always been members, the presence of “second line” functions is a relatively recent phenomenon. Exhibit 15 illustrates the rise of the CRO and the COO—who is usually also responsible for technology. It is interesting to note that few banks have actually made a “stand-alone” CIO/CTO a member of the executive committee. The increasing presence of CEOs of significant subsidiaries is also notable.

Broadly speaking, we see two models employed by peer banks:

- The first one consists of a large executive committee which brings together most functions and business/sub-businesses of the bank irrespective of seniority rank and extent of delegated authority: for example, the “Management Team” of SAN consists of 31 members while BBVA’s “Executive Leadership Team” comprises of 21 members. Similarly, HSBC’s “Senior Management”, SEB’s “Group Executive Committee” and UCG’s “Executive Management Committee” have 17 members. The size of the committee ensures that all key personnel are around the table. The downside is of course that nimbleness and the quality of the debate may suffer.

- The second one includes a smaller executive committee with a much broader committee under it: the two French banks are the main examples of this approach. Over the last 2 years, SOCGEN has shrunk its executive committee to five members, including the CEO and four deputy CEOs with responsibilities over all the functions and businesses of the bank. Below this committee, there are three strategy committees which have a “vertical” view on key issues while overcoming silos. Finally, a much broader 60-member group management committee meets on a quarterly basis to co-ordinate business and cross-fertilize ideas. A more hierarchical but fairly similar model is that of BNP, with a small 6-member executive committee comprising of the CEO, COO and four Deputy CEOs and a large Executive Committee consisting of the General Management and 14 Heads of Core Businesses and Central Functions. Both meet at least once a week.

Over the last decade, executive committees have grown in size and their composition has also changed.

There are also two models in the way decision making authority is cascaded through the organisation in a unitary board. A few boards vest the executive committee with formal authorities as a collective body—turning it effectively into an executive board. At KBC, for instance, the Executive Committee has collective delegated authorities from the board; they are then delegated to the CEO, CRO and others, who can further delegate.

In contrast, most peer banks do not delegate any authority to their executive committees who are in effect advisory bodies to the CEO—or to others with authority around the table. In several banks, all authorities for running the bank (excluding the board’s retained authorities) are delegated to the CEO who sub-delegates to other members of senior management. This is for example the case at CBA or LLOY.

Some banks employ a “hybrid” approach: the board assigns to the CEO specific powers and authorities but also assigns specific authorities to senior executives, General Managers and even Assistant General Managers (e.g. Group CCO, Corporate Governance Officer, General Manager of Legal Services etc).

Another “hybrid” approach is adopted by INTESA: top management has collective delegated authority, but it is the CEO who has the exclusive initiative to propose decisions.

In most cases, the executive committee’s ToRs would specify the committee’s responsibilities even when they are not matched by collective delegated authority.

The above models refer to non-credit executive decision making. The situation is quite different when it comes to credit decisions. In the great majority of banks, these decisions are delegated to collective bodies, at least when they reach significant amounts. The delegation is usually part of the credit policy approved by the board.

There are different approaches as regards executive committee authorities among unitary boards. Most have an advisory role to the CEO and only a few have specific delegated authority.

When it comes to broader risk management, most peer banks have a top-level management risk committee (Exhibit 16).

For example, LLOY has a Group Risk (management) Committee which sits at the top of several “second level” risk committees (namely Credit Risk Committees, Group Market Risk Committee, Group Conduct, Compliance and Operational Risk Committee, Group Financial Risk Committee, Group Capital Risk Committee, Group Model Governance Committee, Group Fraud and Financial Crime Committee, Ring-Fenced Bank Perimeter Oversight Committee). The “pyramid” is slightly different for BARC: it also has a Group Risk (management) Committee which stands on top of several functional “second level” risk committees. But the Group Risk Committee is also at the apex of a system of business unit risk committees providing a more direct access to the front line’s “pulse”.

The above suggest that, in most banks, one can identify two “funnels” of bottom-up reporting and top-down direction between board and management: one is used for strategy and executive decision making at the bank; while the other is used for risk-related information and management.

While top management risk committees in most banks might have a slightly different make-up than the executive committee, allowing for direct participation of some second line functions or some risk-sensitive businesses (e.g. treasury), a number of banks use the executive committee as the top management risk committee, sometimes changing its name (and in some cases, its chair) and holding special meetings. DANSKE for example has an executive board which has overall responsibility for risk management and established a risk committee which consists of all the members of the executive board while, at HSBC, the Group Management Board holds a risk management meeting to support the CRO in exercising board-delegated risk management authority. Similarly, the board of managing directors at CBA defines the risk policy guidelines and delegates operative risk management to committees.

There are usually two “funnels” of decision-making related information between the management and the board, supported by a structure of management committees: one covers strategic and business issues while the other covers risk oversight (and runs through the BRC).

Another important aspect of the authority structure is the way responsibility, authority and decision making are mapped. One can discern two stylised approaches: one was pioneered a couple of decades ago by the Swiss regulator and banks: there is a central, fairly detailed “map” of authority. It tracks initiation, discussion, decision and information of all major areas of decision making. The UK’s recent SMCR has taken a page of the Swiss book to impose centralised “responsibility maps” that identify the key individuals that assume “prescribed responsibilities” in their individual “statements of responsibility” and presents a whole picture of their distribution.

The alternative is piecemeal documentation of key individual and collective responsibilities across various job descriptions, board decisions/minutes and ToRs. Surprisingly, this approach is still prevalent in many banks in Europe and the US. In Europe, the EBA’s Guidelines suggest a switch to a more centralised “map”, and the Single Supervisory Mechanism (the “SSM”) is reportedly following suit in terms of its expectations.

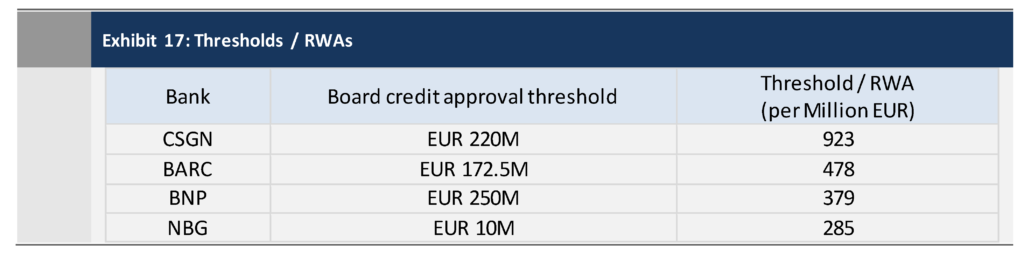

Turning to the board’s retained authorities, a key differentiation among banks is the degree of credit authority that the boards keep for themselves. Some banks like SOCGEN and CMB delegate all credit authority to management. However, retention of some credit authority for very large exposures still seems to be the norm. Exhibit 17 indicates that there are still large differences in the board’s retained credit authority. We compare the extent of this authority by “normalising” limits in relation to the risk weighted assets (the “RWAs”) of each bank.

The complete publication, including footnotes and appendix, is available here.

Print

Print