Bruce Shaw and Ariel Babcock are Managing Directors, Research and Victoria Tellez is a Research Associate at FCLTGlobal. This post is based on their FCLTGlobal memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Myth that Insulating Boards Serves Long-Term Value by Lucian Bebchuk (discussed on the Forum here).

Executive Summary

Operating at the nexus of short-term performance pressures and the behaviors that promote long-term value creation within the firm, the chief financial officer (CFO) has a unique ability to drive long-term value creation for the organization. Among their growing set of responsibilities, CFOs and their teams report company financial results, communicate with and field questions from investors, secure financing to fund corporate strategies, and act as a strategic resource for the chief executive officer (CEO) and board of directors.

CFOs need to manage legitimate short-term performance pressures and, at the same time, advocate for capital allocation decisions with long-term benefits, even if potential contributions to corporate earnings are years in the future. CFOs are essential to driving long-term behaviors and are in a unique position to make a meaningful difference. According to one leading academic, “There’s a huge opportunity for CFOs to focus firms on what truly matters.”

Based on input from FCLTGlobal’s Long-term CFO Initiative (which included two FCLTGlobal member working groups and more than 60 one-on-one interviews—sourced from multiple geographies) and available research, this paper highlights key pressures and obstacles that CFOs encounter, considers the CFO’s unique role as a fulcrum for long-term behavior, assesses the CFO’s intrinsic long-term focus, and recommends the following four long-term levers readily available to the CFO:

- Presenting the right information. Instead of focusing first on what’s required for compliance, CFOs can choose the information to prioritize with important audiences—including investors, the board, and the internal organization—and use that information to drive longer-term conversations and behavior.

- Leveraging forecasts with longer time horizons. By distinguishing forecasts from annual budgets and requiring longer forecasting time horizons (three to five years or more), CFOs can reframe the value of the forecasting process. This approach creates space for internal consideration of initiatives with longer-term contributions—and gives management teams the ability to make adjustments now if the forecasted future is not to their liking.

- Quantifying risks and intangibles. Risk management remains an essential element of corporate governance, but it is primarily focused on avoiding negative surprises. However, management teams can also leverage quantification of risks and intangibles as a proactive way to promote long-term thinking and behavior.

- Aligning capital allocation with long-term strategy. CFOs may not own the strategic planning process, but they can require consistency in capital allocation decision-making in support of the organization’s long-term strategic goals. Capital allocation is the ultimate reflection of company strategy, and CFOs have the ability to require a stronger connection between business unit investment actions and long-term strategic objectives.

CFOs interested in driving long-term value creation can use these findings as a reference checklist to encourage long-term behaviors across their organizations. Those who work with CFOs (boards, C-suite executives, CFO direct reports, and external professionals) can also use these tools to support and challenge senior finance executives and their teams.

Building Long-term Value: A Blueprint for CFOs

As demonstrated by research from FCLTGlobal, McKinsey & Company, and others, long-term companies outperform their counterparts on a number of important dimensions. As measured from 2001 to 2014, long-term firms generated superior growth in revenues and economic profit when compared with others, 47% better in revenue and 81% better in economic profit. They also created more than twice as many jobs on average, outpacing others by better than 130%. However, behaving in a way that creates long-term value can be difficult in an environment where short-term performance often receives a disproportionate share of attention.

When it comes to managing the multiple demands on a company, the CFO has a unique role within the C-suite—responsible for both managing short-term performance pressures and driving behaviors that support long-term value creation.

What pressures do CFOs face? How are CFOs uniquely positioned? Where does the CFO’s long-term focus originate? And what practical actions can a CFO take to navigate short-term and long-term tradeoffs?

Pressures and Obstacles

Studies confirm that CFOs, like other senior executives, encounter short-term pressures:

- 87% of executives and directors feel most pressured to demonstrate strong financial performance in two years or less.

- 80% of financial executives would cut discretionary spending on research and development, advertising, maintenance, or hiring to meet short-term earnings targets.

- 40% of CFOs would give discounts to customers to make purchases this quarter rather than next.

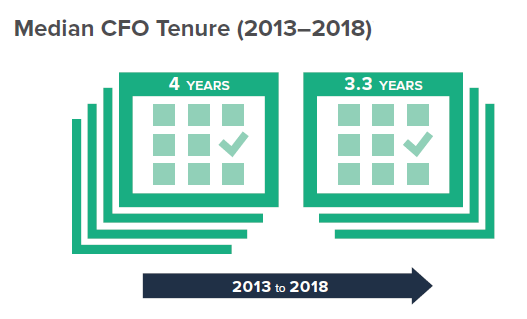

CFOs also encounter a number of obstacles that can get in the way of long-term behaviors. From 2013 to 2018, median CFO tenure decreased from 4 years to 3.3 years, though longer CFO tenures are positively correlated with returns on capital. Executive compensation incentives remain relatively short-term in nature; the average duration of executive compensation is less than two years. Competitors take actions that companies have to address in the near term (whether they are value creating or not). CFOs may have blind spots, at least initially when they take the job, based on the path they traveled on the way to the role. And, finally, CFOs are sometimes unwittingly their own worst enemies, failing to delegate or to challenge the status quo.

A “One-Of-A-Kind” Role

At the same time, CFOs are uniquely positioned to influence the focus of an organization given their responsibilities and the key constituencies they serve. First, CFOs have responsibilities for functional areas that span the short- and long-term divide:

- measuring and driving performance;

- managing cash and sources of funding;

- communicating with boards and capital providers;

- managing risk and regulation; and

- managing investment, divestitures, and portfolios of businesses.

As they carry out these responsibilities, CFOs serve key constituencies that have stakes in company performance, including the board of directors, the CEO/C-suite, investors, banks, providers of debt and equity capital, and the media and general public.

Taking both their responsibilities and constituencies served together, the CFO is typically the only C-level executive who:

- is responsible for preparing and reporting on the company’s short-term results and performance;

- acts as the interface between investors and the CEO/board;

- manages day-to-day liquidity and secures funding for the firm’s long-term capital needs;

- prepares company-wide forecasts and annual budgets; and

- provides financial criteria and modeling support for future investment decisions.

Intrinsic Long-Term Focus

CFOs, then, have a unique ability to promote long-term behaviors while also managing short-term performance pressures, but why should they care? What if they lack an explicit long-term directive from their board or CEO? Many point to the expanding role of the CFO: a 2018 McKinsey survey confirms that the number of functional areas reporting to the CFO continues to increase, growing from an average of 4.5 departments in 2016 to 6.2 in 2018. Others contend that, more and more, the CEO and board see CFOs as strategic thought partners. While both of these developments have benefited companies and the CFO as an executive leader, FCLTGlobal research confirms that long-term thinking is hardwired into the most basic of corporate finance responsibilities (even if not all finance executives choose to leverage it), namely stewarding decisions that grow future cash flows, which ultimately form the basis for the company’s value.

If CFOs are essential to driving long-term behavior, have a unique ability to make a meaningful difference, and are supported by a job description with an intrinsic long-term focus, what actions are open to them?

Throughout the 2019 Long-term CFO Initiative, FCLTGlobal gathered input from its members, subject matter experts, and academic research, ultimately identifying four long-term levers—presenting the right information, leveraging forecasts with longer time horizons, quantifying risks and intangibles, and aligning capital allocation with long-term strategy—that CFOs can employ to drive actual changes in day-to-day thinking and behaviors.

Presenting the Right Information

Quarterly results often grab headlines, but CFOs who take the initiative when communicating with key audiences have demonstrated an ability to focus the conversation on the company’s progress toward longer-term goals and improve investors’ understanding of the company’s future cash flows. In addition, a recent study confirms that companies are missing the opportunity to discuss what investors are most interested in, the company’s outlook over a longer time horizon. Even with internal audiences, including boards of directors, CFOs often spend too much time on short-term performance since, as one subject matter expert noted, “companies often don’t have the plumbing in place to easily measure longer-term KPIs.”

Long-Term “Power Metrics”

When Amy Hood took on the CFO role at Microsoft, she wanted investors to not only understand how the software giant’s existing products were performing but also how well Microsoft was doing relative to longer-term business milestones that would support future revenue streams. She and her team began regularly publishing what they termed “power metrics,” including, for example, commercial cloud revenue growth and annualized run rate—which acted as an indicator for how the company was doing in driving adoption of cloud services (a long-term objective) relative to traditional software sales. Without ignoring short-term performance reporting, the Microsoft team reframed investor discussions to prioritize what management believed would drive the long-term cash flows of the company. Prior to introducing the new metrics in 2015, Microsoft’s market capitalization was $382 billion (December 2014); the company’s current market capitalization is $1.03 trilli9n—an increase of 2.7x compared to 2.0x for the NASDAQ Index.

Board Engagement

New research asserts that boards perform best when management presentations don’t fill the board’s agenda from top to bottom. The most effective board chairs allow at most just 15% of board meeting time for presentations, while one experienced board chair requires executive summaries for all slide presentations and limits each slide deck to 15 pages or less. Even if the best boards limit the time for prepared presentations, CFOs have flexibility when they consider which materials they share with the board and in what order. And though the CFO does not control the board agenda, the board chair and committee chairs often ask the CEO and CFO (and other C-suite executives) for feedback on draft agendas—and this is where proactive CFOs can make a difference. As one professional who has significant experience with boards and the C-suite observed, “Boards tend to think about what management puts in front of them.” One former Fortune 500 CFO recommends an approach that includes prioritizing the five-year and 10-year return on invested capital performance, covering the three-to-five-year investment pipeline, and describing the long-term funding plan—and then finishing by requesting board feedback on a new long-term uncertainty or risk at each meeting.

Organizational Education

Regular firm-wide employee gatherings serve many useful purposes. FCLTGlobal research found that during these sessions, CFOs can often miss the opportunity to educate the broader organization. Several practitioners and subject matter experts pointed out that one of the CFO’s key responsibilities is to ensure employees understand how value is actually created—and how the market recognizes that value over time. A CFO of a leading investment management firm said to achieve this goal he simply reversed the order in which he presented financial results, starting with the trailing five-year return on invested capital and then turning to shorter-term performance, deemphasizing short-term results without glossing over them. Another CFO recommended setting aside five minutes to cover a different “Finance 101” topic at each employee meeting. The objective is to create an organization that is literate in corporate finance basics, which at the heart are focused on future cash flows.

Leveraging Forecasts with Longer Time Horizons

Input from FCLTGlobal working groups and one-on-one CFO interviews confirms that business forecasts can be better utilized to drive long-term thinking within the firm. Forecasts can be confused with annual budgets and can suffer from time horizons that are too short. In addition, business unit leadership teams often misunderstand the real value of forecasts, viewing them as projections they are at risk of missing instead of an iterative tool to improve long-term thinking.

Table 1. Annual budgets versus forecasts

| Annual Budget | Business Forecast | |

|---|---|---|

| Time horizon | One year | Three to five years (or more) |

| Update frequency | Static | Dynamic, rolling as new information is available |

| Purpose | Cost control, near-term revenue signals |

Future cash flow potential, resource requirements |

Forecasts versus Annual Budgets

Annual budgets are important tools for controlling costs and raising awareness of near-term industry shifts or changes in customer behavior that can show up in monthly or quarterly revenue variances. However, managers can confuse the forecast with annual budgets, viewing the forecast as just a longer version of the budget. As a first step, CFOs can separate the two processes with a bright line and invest time with business unit leaders on the distinctive value of each. Budgets are static while forecasts are rolling, and budgets (by definition) are typically one year to match the fiscal year but forecasts have longer time horizons (three to five years or more).

Time Horizons

According to a 2014 Harvard Business Review article, nearly 90% of board members and C-suite executives expressed confidence that using a longer time horizon to make business decisions would positively affect corporate performance, and yet almost half admitted that they set strategy using a time horizon of three years or less. Teams default to shorter time horizons because they are easier to construct and have fewer uncertainties to map out, but shorter timelines undermine a key value of the forecast—to highlight benefits of investments that won’t materialize in the next one to two years. As Harvard Business School professor C. Fritz Foley and Pantheon CFO Mark Khavkin highlighted in a recent Harvard Business Review digital article, CFOs can leverage forecasts with longer time horizons as a key tool in addressing this disconnect since the best forecasts have a time horizon of three to five years or more.

Forecast Value Reframed

British statistician George Box once observed that “essentially, all models are wrong, but some are useful.” A forecast is not intended to be a highly accurate prediction of the future; instead, according to a former Fortune 500 CFO, “a good forecast process will unmask emerging issues and give you enough time to deal with them; if you don’t like the forecasted future, you have time to make changes in your business that get you to a better place.” If business unit leaders view forecasts as measuring sticks that will likely be used against them in the future, not only will they be reluctant to embrace the process and longer time horizons, but they will also miss the real point of the forecast. CFOs have the opportunity to reframe the value of the forecast as a forward-looking tool to assist in future value creation instead of a backward-looking “how well did we do?” exercise.

Elements of a Great Forecast with BP as an Example

Includes projections of operating results and resource needs for the next three to five years

In early 2018, BP projected its capital expenditures ($15–$17 billion per year), divestments ($2–$3 billion per year), debt-to-equity ratios (20%–30%), return on average capital employed (>10%), and free cash flows (by segment, see example below) through 2021.

Reflects the firm’s industry context (e.g., size of total addressable market)

BP’s forecast is grounded in the company’s annual Energy Outlook, a long-term macroeconomic forecast that projects energy supply and demand out through 2040 by region, supply source, and demand type.

Projects future growth rates and margins based on expected competitive dynamics

For its upstream segment, BP projected $6.9 billion in free cash flow growing to $13–$14 billion by 2021 (17%–19% compound annual growth rate), assuming $55/barrel Brent crude price (based on base case supply/ demand forecasts).

Outlines action items for nonfinancial executives and their teams

Within the upstream segment, BP identified more than 1,300 wells with superior returns at base scenario crude prices—outlining which wells to drill (and in which order) for business unit leaders under forecasted conditions.

Quantifying Risks and Intangibles

Since the corporate scandals of the early 2000s and the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, risk management has gained more attention, showing up on almost every corporate radar. However, at least one recent survey confirms that boards still spend less than 9% of their time on risk and that a reactive approach toward risk management is still too common. In the course of this project, FCLTGlobal research confirmed that the CFO’s role in risk management starts with avoiding high-impact, company-wide surprises, but it also entails leveraging quantification of risks and intangibles as a way to encourage longer-term thinking and behaviors.

High-Impact, Company-Wide Risks

As one asset manager put it, “Companies must do everything they can to avoid single event, massive impact risks because they suck all the air from the room and make it hard to focus on the long-term.” This finding is consistent with FCLTGlobal’s 2018 paper Balancing Act: Managing Risks across Multiple Time Horizons. Although written for an investor audience, CFOs can find some helpful tools there, including:

- identifying the top three to five long-term risks and opportunities;

- scenario planning to anticipate how the organization may respond to key risks;

- identifying appropriate measures of risk; and

- identifying short-term risks that could derail the strategy.

But for the CFO, addressing risks and intangibles can be about more than risk avoidance.

Risk Quantification

Several research respondents pointed out that companies don’t spend enough time quantifying future risks and intangibles. One former Fortune 500 CFO asserted that “business schools under-teach risk; adjusted discount rates are worthless—finance teams need to construct better cash flow scenario modeling to… understand the full range of likely outcomes and really thoughtfully debate and quantify the risks.” Linked with forecasting but worth its own focus, the process of quantifying risks and intangibles is impossible without long-term thinking. Rather than using the same cash flows and model assumptions, and then inching the discount rate higher to factor in more risk, teams can construct several plausible scenarios by adjusting cash flows to reflect changes in potential future realities, including risks and intangibles that affect cash flow. Additionally, this gives CFOs the ability to bring other intangibles into the modeling, including those related to climate change, technological disruption, or societal changes.

New Key Performance Indicators and Performance Measurement

Drawing a connection between risk quantification and performance measurement, a senior financial reporting executive commented, “We must work harder to quantify (or create new key performance indicators for) longer-term intangibles; our CFO office is trying to make our impact on sustainability more measurable.” For example, DSM (a purpose-led, science-based company active in nutrition, health, and sustainable living) aligns strategy objectives with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and proactively seeks out new ways to measure its progress. Once developed, these new measures can be leveraged in other performance-related areas, including employee compensation plans.

Aligning Capital Allocation with Long-term Strategy

In 2018, 95% of reported earnings for S&P 500 companies was spent on dividends and stock buybacks. But the evidence shows companies that have directed more dollars to capital expenditures have outperformed their peers, with 55% higher returns on assets and 65% higher sales growth. In addition, management teams that apply a more dynamic approach to capital allocation create more value for shareholders when measured over periods of three years or more. Despite these findings, companies often struggle to execute a more dynamic capital allocation process, and roughly one-third of global firms have no discernible change in investments from one year to the next.

By ensuring a stronger connection between capital allocation decisions and long-term strategic objectives, CFOs have a significant opportunity to close this gap and promote longer-term thinking within the firm.

Corporate Strategy and Capital Allocation

FCLTGlobal interviewees agreed CFOs can exert significant influence over investment decisions by aligning the capital allocation process with long-term corporate strategy: “the CFO creates a capital allocation framework to execute the CEO’s strategy.” Unlike business unit leaders, the CFO can look across the company and see how investments in one area can benefit the whole relative to other options. An investment management firm CFO observed that “it takes a good bit of internal education to link long-term strategy to the pot of money set aside for capital investment.”

CFOs can start by defining investment areas that fit with company strategy so that business unit leaders (and investors on a more general level) know what’s “in” and what’s “out.” A simple next step is requiring business unit leaders to include a brief one-to-two-sentence description of how a project fits with company strategy—and what that fit will look like over different future time periods (one, five, and 10 years, for example) in terms of contributions further out on the horizon.

Robust Process

Companies that reallocate more resources (i.e., don’t follow the same patterns of capital spending year after year) generated 30% higher total returns to shareholders than those who stick to a more static capital allocation pattern, but management teams find it easier to follow historical investment patterns. The causes for static capital allocation range from politics (“division presidents don’t ever want to get less than last year”) to organizational inertia to behavior biases like anchoring, a cognitive bias that leads an individual to rely too heavily on initial (or historical) information provided when making decisions or estimates. To combat these obstacles, CFOs have found a few helpful tools, including:

- evaluating opportunities at regular intervals and in groups so that tradeoffs are always in view;

- using a target portfolio that allocates capital to (for example) new, growing, mature, and declining businesses;

- appointing a “pushback” team to challenge assumptions and suggest alternatives; and

- reviewing past decisions in a rigorous way and keeping a running list of learnings.

Public Guidelines

Though companies can’t make public all aspects of their capital allocation policies and processes, they can communicate the basic outline of what drives decision-making and how the company thinks about investment options in light of long-term strategy. CFOs and investor relations executives find that publishing such a guide provides a framework for lining up near-term company actions with long-term objectives. For example, BHP hosted a “capital allocation briefing” for investors during which its CFO, Peter Beaven, summarized the company’s more transparent process, how it supports corporate strategy, and how it will provide superior returns over a long-term time horizon. BHP believes the transparency will attract longer-term investors, and even if some investors take issue with parts of the outline, at least they know what to expect.

Conclusion

Given their responsibilities and key constituencies, CFOs are uniquely positioned to influence the focus of the firm. An experienced board member described the CFO as “the conscience of the company,” and a business unit president describes the CFO as “the truth teller on the business.”

And because the firm’s current valuation is directly linked to future cash flows, the long-term focus is intrinsic to the fabric of the CFO’s office—with or without an explicit directive.

FCLTGlobal research confirms that CFOs can make a meaningful difference in promoting long-term thinking and behaviors within their firms while also managing short-term performance pressures by considering the following long-term action levers:

- Presenting the right information

- Leveraging forecasts with longer time horizons

- Quantifying risks and intangibles

- Aligning capital allocation with long-term strategy

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print