Brian Tayan is a Researcher with the Corporate Governance Research Initiative at Stanford Graduate School of Business. This post is based on a recent paper by Mr. Tayan; David F. Larcker, James Irvin Miller Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; John D. Kepler, Assistant Professor of Accounting at Stanford Graduate School of Business; and Daniel Taylor, Associate Professor of Accounting at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Insider Trading Via the Corporation by Jesse Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

We recently published a paper, Governance of Corporate Insider Equity Trades, that examines the potential shortcomings of existing governance practices around the approval of executive equity sales. Corporate executives receive a considerable portion of their compensation in the form of equity (e.g., stock, options, or restricted stock) and, from time to time, sell a portion of their equity holdings in the open market. Executives nearly always have access to nonpublic information about the company, and routinely have an information advantage over public shareholders. This raises the possibility that some executives might exploit this advantage for personal gain and trade on nonpublic information.

Federal securities laws prohibit executives from trading on material nonpublic information about their company. Officers and directors have a fiduciary duty to shareholders that compels them to either disclose any material, non-public information to shareholders or abstain from trading—a rule known informally as ‘disclose or abstain.’ Under Rule 10b5-1, insiders can enter into a non-binding contract that instructs an independent third-party broker to execute trades on their behalf (10b5-1 plan). If the plan is adopted at a time when the insider is not in possession of material nonpublic information, the plan will provide an “affirmative defense” against alleged violations of insider trading laws. Regardless of whether executives use a 10b5-1 plan, the SEC requires that they publicly disclose their trades in the company’s shares within two-business days on Form 4.

To ensure executives comply with applicable rules, companies develop an Insider Trading Policy (ITP) which specifies the procedures by which an insider may trade in company stock. The purpose of a well-designed ITP is two-fold. First, the ITP ensures all trades comply with the law and that corporate officers and directors fulfill their fiduciary duty to shareholders. Second, the ITP minimizes the risk of negative public perception, reputational damage, or legal consequences that arise from trades that—while not illegal—might happen to be timed in such a way that they appear suspicious. In this regard, a well-designed ITP is critical to the company’s corporate governance: It goes beyond ensuring trades comply with securities laws and more broadly reduces governance risk to the company.

The typical ITP designates periods during which trading is prohibited (trading blackout periods). Trading blackout periods typically precede earnings announcements and the release of other material information. In addition to specifying blackout periods, the ITP also specifies whether trades must be pre-approved by the general counsel, as well as rules governing the creation of 10b5-1 plans. Academic research documents substantial variation across companies in the length of blackout periods, the types of corporate events that trigger blackout periods, and the extent to which firms (and by extension general counsels) enforce the ITP. Best practices are to publicly disclose the ITP and indicate whether any trades were made under a 10b5-1 plan. However, current SEC rules do not require disclosure of the ITP, the existence of a 10b5-1 plan, or whether a trade is made pursuant to such a plan.

Despite procedures designed to ensure compliance with applicable rules, news media and the public tend to be suspicious of large-scale executive stock sales. This is particularly the case when a sale occurs prior to significant negative news that drives down the stock price. Public suspicion is exacerbated by inconsistent and non-transparent corporate practices—such as, lack of communication around why the sale was made, whether the general counsel approved the trade in advance, and whether the trade was the result of a 10b5-1 plan—and differing opinions about what constitutes “material” nonpublic information. Thus, an executive stock sale might pass the legal test but fail the “smell test” employed by the general public. A well-designed ITP lessens the likelihood of such a scenario.

In this Closer Look, we examine a series of trades by officers and directors that have unusual elements (such as their timing, size, or lack of disclosure) to illustrate pressing issues on the governance of insider trades. Specifically, we consider two vignettes on nonpublic information about product defects (Boeing and Intuitive Surgical) and two vignettes on nonpublic information about cybersecurity vulnerabilities in company’s products and customer databases (Intel and Equifax). While many of these trades do not violate federal securities laws, the circumstances are nonetheless instructive on the potential shortcomings of existing practices and suggest significant room for improvement in internal governance practices.

Product Defects

Our first two vignettes relate to nonpublic information about the company’s products.

Boeing

In October 2018, a Boeing 737 MAX aircraft crashed because of a software failure, killing 189 people. While Boeing engineers were aware of the software issue prior to the crash, it was not brought to the attention of senior management until after the crash. According to the Wall Street Journal:

“It was only after a second MAX accident in Ethiopia nearly five months later, [industry and government] officials said, that Boeing became more forthcoming with airlines about the problem. And the company didn’t publicly disclose the software error behind the problem for another six weeks, in the interim leaving the flying public and, according to a Federal Aviation Administration spokesman, the agency’s acting chief unaware.”

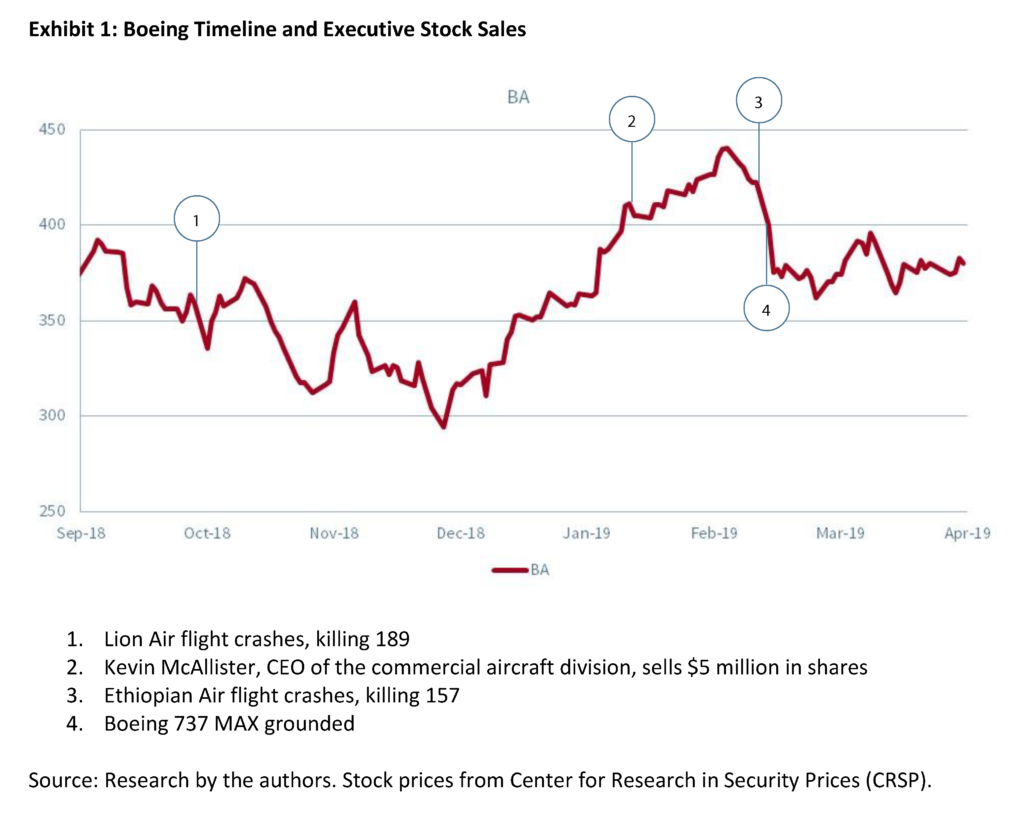

In the intervening period, during February 2019, Kevin McAllister, CEO of the commercial aircraft division of Boeing, sold $5 million worth of stock in a single transaction. The transaction occurred the same day Boeing filed its 10-K, which made no mention of any issues related to the 737 MAX. It was McAllister’s first sale since joining the company in 2016, and there was no disclosure that the trade was pursuant to a 10b5-1 plan. The following month, a second 737 MAX aircraft crashed due to the same failure, killing 157. The next day, government agencies around the world grounded the Boeing 737 MAX aircraft and ordered a safety review. Following the controversy surrounding the 737 MAX, the board of directors ousted McAllister in October 2019 and CEO Dennis Muilenburg in December 2019 (see Exhibit 1).

Intuitive Surgical

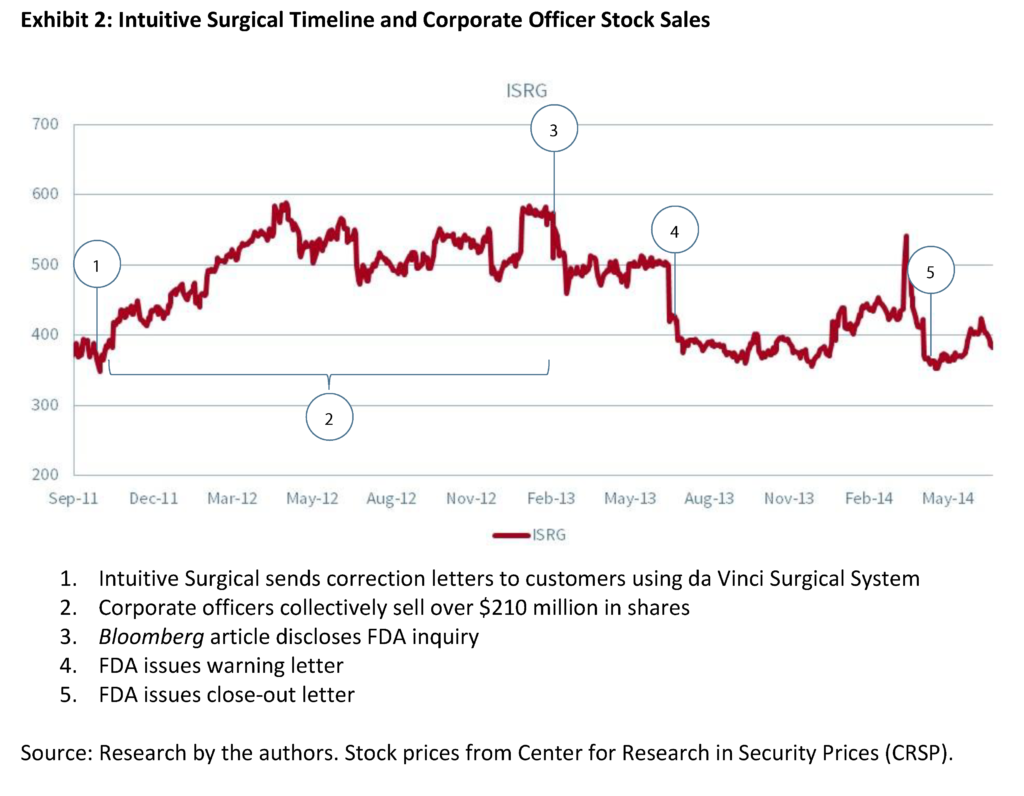

The da Vinci Surgical System, manufactured by Intuitive Surgical, is a robotic surgical system that performs minimally invasive gynecological, prostate-removal, and soft-tissue surgeries. In October 2011, Intuitive Surgical sent correction letters to hospitals to notify them of a potential failure in the rubber tip cover designed to prevent electric sparks (“arcing”) that could damage surrounding tissue and lead to hemorrhaging. At the time, the company did not notify the Food and Drug Administration or the public. A year-and-a half later—February 2013—Bloomberg News reported that the FDA had opened a safety probe into the product. It was the first public notification of FDA interest in the da Vinci System. News of the inquiry triggered an 11 percent drop in the company’s stock. Two weeks later, the company announced that it would change its categorization method for reporting adverse incidents to the FDA and recategorize certain previous events from “other” incidents to “serious injury.” The FDA issued a public warning letter in July 2013, which was closed in April 2014.

During the 17-month period following the initial corrective letter sent to clients (October 2011) and news of the FDA’s safety probe (February 2013), corporate officers of Intuitive Surgical—including its CEO, CFO, chairman and others—collectively exercised options and sold over $210 million of stock some but not all of which were made pursuant to 10b5-1 plans (see Exhibit 2). Shareholders sued the company and its officers for breach of fiduciary duty and unjust enrichment. The company settled, and the officers agreed to reimburse Intuitive Surgical $15 million in the form of cash and forfeited options. The company also agreed to make changes to its Insider Trading Policy, including a requirement that all executive stock sales be made using 10b5-1 plans.

- Should knowledge of product defects be considered material nonpublic information?

- Does fiduciary duty compel insiders to either disclose product defects or abstain from trading?

- Should the ITP prohibit trading in the period between when product defects are discovered and when they are disclosed?

- Should executives be allowed to trade on the same day the firm files financial statements with the SEC?

- Should companies require that all executive stock sales be made using 10b5-1 plans?

Cybersecurity

Insider trading on knowledge of cybersecurity vulnerabilities is more common than expected, and the SEC cautions “information about a company’s cybersecurity risks and incidents may be material nonpublic information.” Our next two vignettes relate to security vulnerabilities in company’s products and customer databases.

Intel

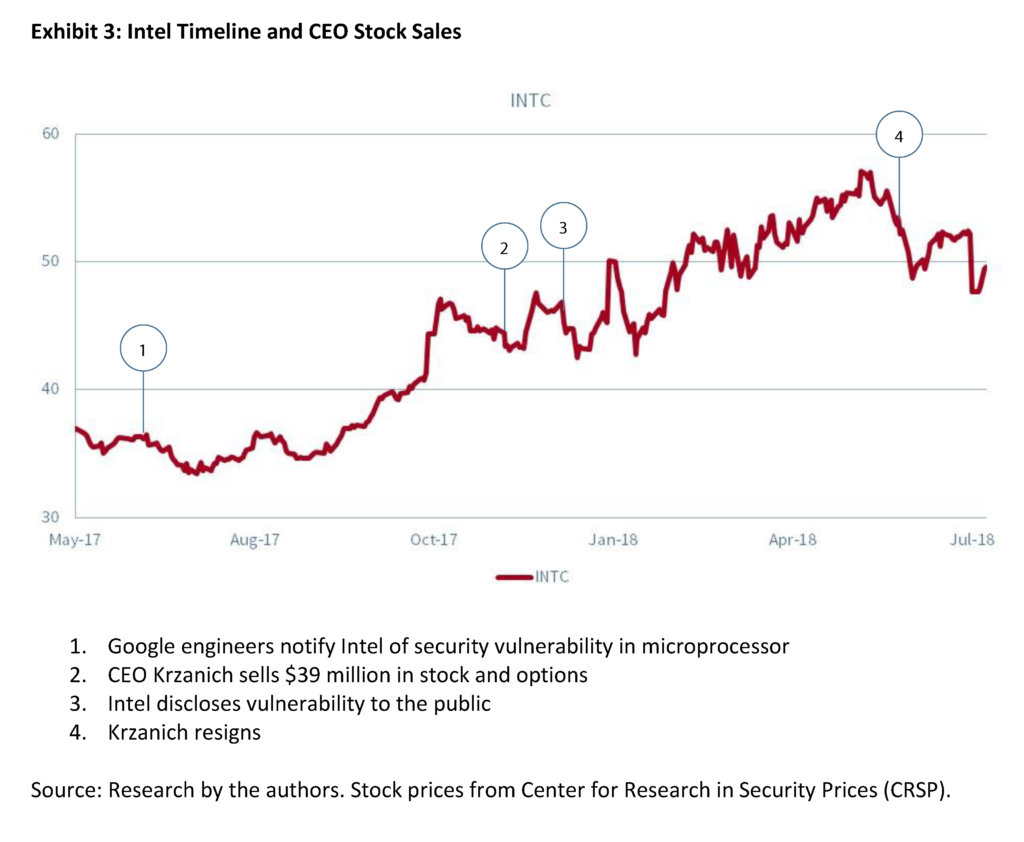

In June and July of 2017, Google engineers notified Intel of security vulnerabilities in their microprocessors. In November 2017, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich sold $39 million of stock in a single day. The Form 4 filing discloses that the trade was made as part of a 10b5-1 plan adopted in October 2017—after Intel was aware of the vulnerability but prior to the public disclosure of the vulnerability. Following the sale, Krzanich retained only the minimum number of shares allowed under the company’s stock ownership guidelines (250,000, valued at approximately $12.5 million at the then-current stock price). Not wanting to disclose the security vulnerability on their processors for the risk of increasing the incidence of cyberattacks, Intel disclosed the security vulnerability on January 3, 2018, and released an update to protect some of the affected systems the following day. Intel’s price declined 9 percent over the following week, and declined 11 percent relative to the S&P 500. In June 2018, Krzanich resigned for unrelated matters (see Exhibit 3).

Equifax

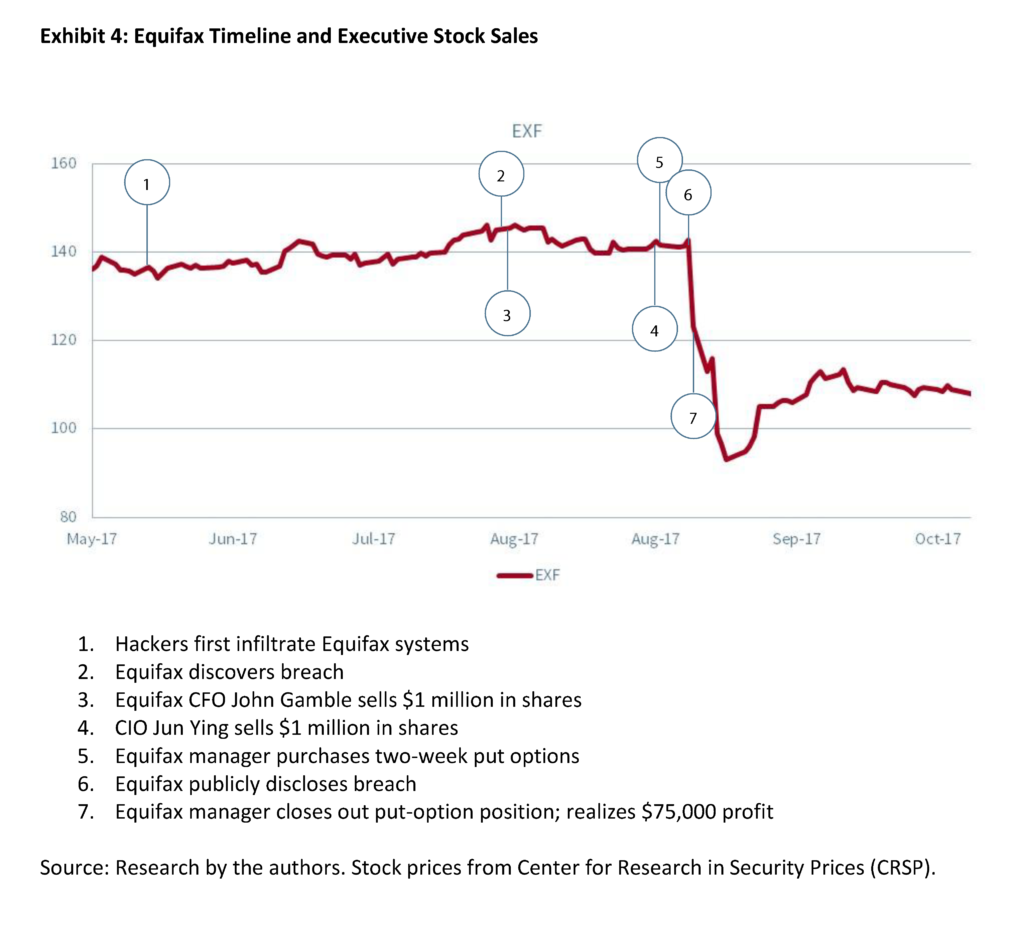

In the summer of 2017, foreign hackers infiltrated Equifax’s servers, accessing the personal information of over 143 million individuals. Equifax discovered the breach July 29. On August 1, Equifax CFO John Gamble sold approximately $1 million worth of shares. August 28, the company’s CIO Jun Ying sold $1 million. September 1, Sudhakar Bonthu, an Equifax software engineering manager, purchased put options with a two-week expiration date. When Equifax publicly disclosed the security breach September 7, its stock declined 14 percent (see Exhibit 4). In July 2019, Equifax agreed to pay $700 million to resolve legal inquiries related to the breach. Ying and Bonthu were purportedly aware of the security breach at the time of their trades and charged with insider trading, but Gamble was not.

- Although major cybersecurity vulnerabilities may constitute material nonpublic information, companies may not wish to disclose them until they are remediated. Does fiduciary duty compel insiders to either disclose the major vulnerability or abstain from trading?

- Should the ITP prohibit trading in the period between when a major security vulnerability is discovered and when it is disclosed?

- Should a 10b5-1 plan be allowed for large single-event stock sales?

- What signal is sent to investors when the CEO sells down to the minimum required ownership?

- Should employees be allowed to trade put and call options on company securities?

Why This Matters

- Executives are routinely in possession of material information about their company. They also routinely sell equity holdings for diversification and consumption purposes. Although SEC rules provide a framework for determining whether executive trades violate the law, many examples of insider stock sales are legally ambiguous. This raises questions about the objectives of a well-designed insider trading policy. Should such a policy merely ensure that executives comply with minimal legal requirements governing their trades, or should the policy minimize the risk of negative public perception, reputational damage, or legal consequences that arise from trades that—while not illegal—might happen to be timed in such a way that they appear suspicious?

- The insider trading policy is an important aspect of the firm’s overall corporate governance and internal control systems. Why don’t companies always make the terms of these policies public?

- Companies vary in the restrictions imposed by their insider trading policy. Why don’t more companies require the strictest standards, such as pre-approval of all trades by the general counsel, or require all senior executives to use 10b5-1 plans for their transactions? Would stricter rules reduce public suspicion around well-timed stock sales?

- Rule 10b5-1 provides an affirmative defense for executives who sell a portion of their holdings in the open market, and several of the examples in this Closer Look involve executives making trades under 10b5-1 plans. Why would an executive not rely on a 10b5-1 plan when selling stock? Why do some executives who use 10b5-1 not disclose the use of this plan on a Form 4?

- Executive stock sales are announced on Form 4 with little additional information. What conversation, if any, takes place between executives and the board around stock sales—particularly large, single-event sales? Does the board review trades by insiders on a regular basis?

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print