Brad S. Karp is chairman and Jessica S. Carey and Roberto J. Gonzalez are partners at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP. This post is based on their Paul, Weiss memorandum.

As the latest chapter in the aftermath of the Wells Fargo fake accounts scandal, on January 23, 2020, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) announced enforcement actions against eight former Wells Fargo executives for their roles in the bank’s “systemic sales practices misconduct.” [1] Five individuals—including the former head of the Community Bank, group risk officer, general counsel, chief auditor, and executive audit director—face a 100-page notice of charges that, if contested, would be heard by an administrative law judge. The OCC is seeking a $25 million penalty and an industry bar against Carrie Tolstedt, the former head of the Community Bank, and lesser penalties against the four other former executives. Three other individuals settled with the OCC, including former Chairman and CEO John Stumpf, who agreed to a $17.5 million penalty and an industry bar. [2]

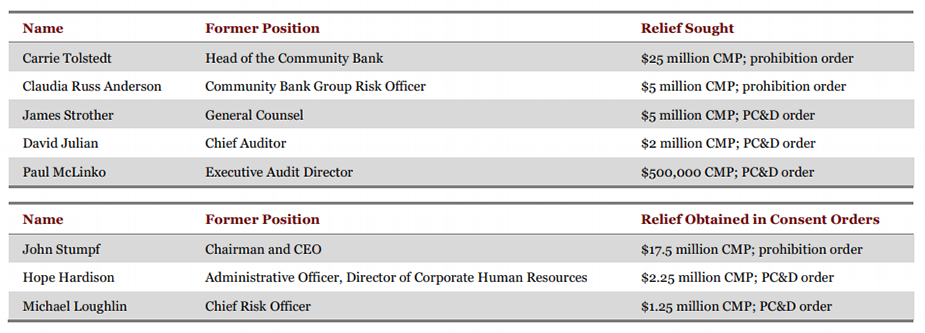

The table below shows the civil monetary penalties sought or settled. According to the OCC, these amounts reflect each individual’s level of culpability and financial resources, including compensation previously clawed back by Wells Fargo.

The OCC’s actions constitute an unprecedented use of the agency’s authority to impose personal liability on bank executives, including leaders of the bank’s legal and control functions. Until now, the highest individual civil monetary penalty imposed by the OCC in the last two decades was $1 million, and most individual penalties have been in the range of $100,000 and under. [3]

As a further comparison, in July 2019, the OCC issued a consent order imposing a $50,000 penalty against the former general counsel of Rabobank, N.A. for concealing from the OCC a consultant report showing anti-money laundering deficiencies, for which the bank pled guilty to obstruction charges. [4] The OCC is seeking a penalty 100 times higher from Wells Fargo’s former general counsel.

The OCC’s notice of charges gives further insight into the OCC’s long-running investigation, quoting internal emails and deposition testimony (each of the respondents was deposed by the OCC, although two invoked the Fifth Amendment). The charges—both in tone and in substance—reflect what appear to be grave concerns by the OCC over what it sees as senior executives who over many years actively supported a business model focused on sales goals while ignoring mounting evidence that these sales goals were unrealistic and caused employees to engage in widespread illegal sales practices. The OCC also alleges that the bank’s attempts to monitor these practices were deliberately calibrated to focus on only the “tip of the iceberg” of employee offenders, while ignoring the vast majority. Some of the executives are also alleged to have presented Wells Fargo’s Board of Directors, and sometimes the OCC, with false and misleading reports that minimized the extent and root cause of these issues. The OCC’s press release specifically calls out the allegation that Respondent Russ Anderson, the Community Bank’s former group risk officer, “made false and misleading statements to the OCC and actively obstructed the OCC’s examinations of the bank’s sales practices.” The notice of charges catalogues the significant financial and reputational harm to Wells Fargo caused by these practices, which a former CEO estimated to total in the “tens of billions of dollars.” The financial harm includes: $185 million in settlements with the OCC, CFPB, and LA City Attorney; a $142 million class action settlement; $70 million for legal representation of the independent directors; $97 million paid to consultants; and “hundreds of millions of dollars” for the bank’s “Re-Established” marketing campaign. The OCC also cited significant reputational harm, including the fact that the bank’s reputation score “‘went into freefall.’”

Comptroller Joseph Otting stated that these actions “reinforce the agency’s expectations that management and employees of national banks and federal savings associations provide fair access to financial services, treat customers fairly, and comply with applicable laws and regulations.” Going forward, it remains to be seen whether the OCC—and possibly other federal and state bank regulators—will have a new willingness to seek multi-million dollar penalties and industry bars against bank executives for promoting and/or failing to correct systemic compliance failures. Alternatively, the Wells Fargo scandal may be an exceptional case that is not indicative of a sea change in enforcement attitudes towards individual accountability.

Below, we summarize key points in the notice of charges and outline lessons learned for other financial institutions.

The OCC’s Notice of Charges Against Five Former Executives

As reflected in the summary below, the notice of charges details the OCC’s allegations about the Community Bank’s business model, the resulting widespread employee misconduct and the mounting evidence of this misconduct, the bank leadership’s inadequate responses, and the incomplete and misleading reporting of these issues to the Board of Directors and the OCC. The notice of charges also describes the OCC’s factual and legal allegations against each Respondent.

The OCC Alleges the Bank’s Flawed Business Model Incentivized Serious Employee Misconduct for Many Years

- The Community Bank (or “bank”) had a “systemic and well-known problem with sales practices misconduct that persisted for at least 14 years, beginning no later than 2002.”

- The root cause of the misconduct was the bank’s “business model, which imposed intentionally unreasonable sales goals and unreasonable pressure on its employees to meet those goals and fostered an atmosphere that perpetuated improper and illegal conduct.” The pressure on employees included monitoring employees daily or hourly, subjecting employees to “hazing-like abuse,” and threatening to terminate and actually terminating employees who did not meet these goals. This “aggressive sales culture” ultimately resulted in “significant employee turnover, approximately 35% annually”; this rate was significantly higher than in peer banks and indicated that sales pressure was “excessive.”

- This business model resulted in greater legitimate sales, but also resulted in the sale of unauthorized products and services, which allowed the bank to inflate its “cross-sell” metric and enhance its stock price. This financially benefited the bank and Respondents. To avoid upsetting a profitable business model, senior executives, including Respondents, “turned a blind eye to illegal and improper conduct across the entire Community Bank.”

- The business model caused “hundreds of thousands of employees” to engage in numerous types of improper sales practices, including: opening and issuing millions of unauthorized checking and savings accounts, debit cards, and credit cards; transferring customer funds between accounts without customer consent (“simulated funding”); misrepresenting to customers that certain products were available only in packages with other products (“bundling”); enrolling customers in online banking and bill-pay without consent (“pinning”); delaying the opening of requested accounts to the next sales reporting period (“sandbagging”); and accessing and falsifying personal customer account information (such as phone numbers, home address, and email addresses) without authorization.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers determined that Wells Fargo employees “opened approximately 3.5 million potentially unauthorized accounts between January 2009 and September 2016.”

- Improper sales practices resulted in violation of various criminal laws (misapplication of bank funds, false records, identity theft, and bank fraud) and consumer protection laws (unfair and deceptive acts and practices and Regulation Z).

- Former CEO John Stumpf admitted, based on the information presented during his testimony to the OCC, that the bank had a systematic sales practices misconduct problem from the early 2000s until sales goals were eliminated in October 2016. He testified that Respondents Tolstedt and Russ Anderson bore “significant responsibility” for the existence and continuation of this problem.

The OCC Alleges Sales Practices Misconduct Was Well-Known for Years

- “The sales practices misconduct problem and its root cause were well-known for years throughout the Bank, including by Respondents.” For years, employees and customers “tried in vain” to alert senior leaders to the growing and continuing problem.

- From 2006 through 2014, nearly half of all EthicsLine complaints investigated by the Corporate Investigations unit related to employee sales integrity violations, defined as manipulations or misrepresentations of sales in an attempt to obtain compensation or reach sales and service goals. As early as 2007, a lack of customer consent was a primary allegation in EthicsLine complaints.

- The former CEO agreed in testimony that employees did all they could to complain about the unreasonable sales goals over many years, including by “calling the EthicsLine, sending emails, holding protests, and approaching newspapers.” Other witnesses corroborated this testimony. The OCC quoted specific employee complaints directed to Respondents Tolstedt and Strother.

- From December 2013 through September 2015, the bank received at least 5,000 customer complaints about lack of consent.

- In one instance in 2012, a former Operating Committee member’s wife received two debit cards she did not request in the mail. (The Operating Committee is the bank’s most senior management committee.) The former committee member raised this with Respondent Tolstedt, who later asked him to stop telling the story because it reflected poorly on the bank.

- A 2004 report prepared by the bank’s Corporate Investigations unit found that in the last four years allegations of employees “gaming” sales increased 979% and associated terminations had increased 962%. The report found that gaming allegations were “geographically consistent corporate-wide.”

- In 2013, the Los Angeles Times published articles detailing the “scope and root cause of the sales practices misconduct problem.” Respondents knew about the articles and so “by 2013 at the latest had no excuse not to take immediate and decisive action.”

- Despite knowledge of the problem and its root cause, there was “great reluctance” by senior management to make any meaningful changes because the business model was “tremendously profitable and central to the Bank’s success.” Moreover, all Respondents were well-compensated over a period of years, “with much of their compensation equity-based, and all profited personally from the improper business model.”

- The flawed business model persisted “because senior management, including Respondents, blamed individual employees for the problem, refused to address the actual root cause, downplayed the problem’s seriousness and scope, and failed to provide accurate and complete reporting on the problem.”

The OCC Alleges the Bank’s Controls Were Intentionally Designed to Prevent Detection of the Overwhelming Majority of Sales Misconduct

- Until the elimination of sales goals in October 2016, the bank’s sales practices controls “were severely deficient in that they were intentionally designed to neither prevent nor detect the vast majority of sales practices misconduct.”

- Only after approximately 2012 did the bank begin monitoring for a few types of sales practices misconduct; prior to this time, employees were generally only caught if another employee learned of misconduct and blew the whistle.

- Even after monitoring was in place, employees were referred for investigation only if they engaged in misconduct so frequently that they “appeared on the Community Bank’s list of the most egregious offenders (top 0.01 or top 0.05% of total offenders).” These thresholds only identified 3 to 18 employees per month, a figure that Respondent Strother described in his OCC testimony as “stunning.”

- Following the Los Angeles Times reporting in 2013, instead of “increasing monitoring of sales practices misconduct,” the bank “paused” proactive monitoring until approximately July 2014 in an “effort to limit the large number of employee terminations for sales practices misconduct.” When monitoring was resumed, the detection threshold was set to identify only those employees in the top 0.01% of activity that was a “red flag” for simulated funding—the bank “literally could not have chosen a lower threshold.” (The bank’s ability to detect simulated funding through data analytics was much greater than its ability to detect other kinds of misconduct.)

- From January 2011 through September 2016, the bank terminated over 5,300 employees for engaging in improper sales practices, but these terminations “were just the tip of the iceberg.” Hundreds of thousands of employees “likely engaged in such misconduct.”

The OCC Alleges Inaccurate and Misleading Reporting to the Board and the OCC

- In April 2015, the OCC conducted an examination at the bank and issued a Matter Requiring Attention (“MRA”) relating to the lack of a formalized governance framework to oversee sales practices. In May 2015, the LA City Attorney filed suit against the bank, alleging various improper sales practices.

- Even after Respondents Tolstedt and Russ Anderson were directed to inform the Board and the OCC about the sales practices misconduct problem, they provided “false, misleading, and incomplete reporting on the root cause, duration, and scope of the problem, and the adequacy of the controls.”

- For example, Respondents Tolstedt and Russ Anderson, with assistance from the Legal Department, prepared a memo for the Board’s Risk Committee meeting in May 2015. The memo was false, misleading, and incomplete because it characterized the problem as “outlier behavior” and falsely stated that controls were effective. The memo was also provided to the OCC.

- Although the CEO had instructed Respondent Tolstedt to include information on the number of products sold without customer consent and termination figures in the memo, the final memo omitted this information, which would have “aided in the Board’s and the OCC’s understanding of the magnitude of the sales practices misconduct problem.”

The OCC‘s Allegations Against Each Respondent

- The Bank’s policies and committees “entrusted Respondents Tolstedt, Russ Anderson, Strother, and Julian with the authority and responsibility to address the sales practices misconduct problem. In reality, the Respondents did no such thing.” The relevant committees included those on incentive compensation, enterprise risk management, team member misconduct, and Community Bank risk management. In many of these committee meetings, these Respondents were provided with information regarding sales practices misconduct, but Respondents failed to act.

- Respondent Tolstedt, the former head of the Community Bank and a member of the Operating Committee, was “directly and significantly” responsible for the business model that incentivized systemic sales practices misconduct over a decade.

- The OCC alleges that Respondent Tolstedt violated several criminal statutes and consumer protection laws, recklessly engaged in unsafe or unsound practices, and breached her fiduciary duty to the bank and engaged in personal dishonesty.

- Respondent Russ Anderson, who served as the bank’s Group Risk Officer from 2004 until August 2016, failed in her first-line responsibility for risk management and controls.

- She also “knowingly and willfully made several false and misleading statements to OCC examiners during the February 2015 and May 2015 examinations and regularly sought to limit the extent of information provided to the OCC.” Among other things, she falsely stated on calls with OCC examiners that “no one loses their job because they did not meet sales goals,” that “customers are not cross-sold any products without first going through a formal needs assessment discussion with a banker,” and that she does not “hear” about pressure from personal bankers “at all” and that “people are positive and pleased.”

- The OCC alleges that Respondent Russ Anderson violated various criminal statutes (adding false statements to the government and obstruction of a bank examination to the list of criminal violations cited against Respondent Tolstedt), recklessly engaged in unsafe or unsound practices, and breached her fiduciary duties to the bank and engaged in personal dishonesty.

- The Law Department and Audit had a responsibility to “ensure incentive compensation plans were designed and operated in accordance with Bank policy, evaluate risk, and ensure it was adequately managed and escalated, advise whether the Community Bank was operating in conformance with laws and regulations, or identify and detail significant or systemic problems in audit reports.” None of the Respondents who held leadership roles in those departments, however, “adequately performed their responsibilities with respect to the sales practices misconduct problem.”

- Respondent Strother served as General Counsel and a member of the Operating Committee from 2004 until his retirement in March 2017.

- Respondent Strother and the Law Department were “instrumental in maintaining the Community Bank’s business model that resulted in rampant criminal and legal violations.” Among other things, the Law Department protected the bank’s ability to terminate employees for not meeting sales goals, and it obtained an exception to the bank’s insurance coverage to allow individuals who engaged in sales practices misconduct to remain employed. The eventual elimination of sales goals in October 2016 “had nothing to do with advice from Respondent Strother or the Law Department.”

- Respondent Strother provided the Board, and the OCC, with false, misleading, and incomplete information about sales practices misconduct. For example, a May 2015 memo stated that only 230 bank employees had been terminated in connection with the bank’s review of sales practices misconduct, yet Respondent Strother knew by no later than April 2014 that the bank terminated 1,000-2,000 employees per year for sales practices-related wrongdoing.

- The OCC does not allege that Respondent Strother violated criminal or civil statutes, but rather alleges that he recklessly engaged in unsafe or unsound practices and breached his fiduciary duties to the bank.

- Respondent Julian was the Chief Auditor and head of Audit from March 2012 to October 2018. Respondent McLinko was an Executive Audit Director responsible for overseeing all Community Bank audits and reported to Respondent Julian from 2012 to 2018.

- Under Respondent Julian’s leadership, “Audit never criticized the Community Bank for its systemic sales practices misconduct problem or identified its root cause in any audit report, despite all the information that he received that the Community Bank had a widespread problem.” Between 2012 and 2016—even after an OCC directive in June 2015 that Audit “reassess their coverage of sales practices and provide an enterprise view”—Audit awarded “high ratings” to the bank in reports covering aspects of sales practices. He was “unable to posit any reasonable explanation why Audit, under his leadership, did not do more than it did.”

- The OCC alleges that Respondents Julian and McLinko recklessly engaged in unsafe or unsound practices and breached their fiduciary duties to the bank.

Implications

In light of the OCC’s unprecedented enforcement actions—which may signal a new willingness to impose tougher penalties on bank executives going forward—board members, CEOs, and legal and control function leaders would be well served to study the notice of charges for lessons learned. These charges should be read in conjunction with other reports and regulatory actions related to the fake accounts scandal, including Wells Fargo’s internal investigation report, the Federal Reserve’s imposition of an asset cap and issuance of letters of reprimand to Board members, and the OCC’s report about its own supervisory lapses, all of which we have analyzed in prior memoranda. [5] Together, these materials suggest the following lessons:

- The importance of centralized, independent control functions, which take a critical attitude towards red flags and have sufficient authority and voice within the company.

- Board responsibility to inquire into red flags, obtain more detailed reporting, and insist on concrete action plans and metrics for corrective action.

- Bolstering the monitoring, analysis, and reporting of employee and customer complaints; analyzing litigation filed against the company for red flags that may warrant internal investigation.

- Greater attention to governance and compliance mechanisms around any use of sales or production goals and incentive compensation.

- Strengthening the company’s ethics and compliance culture and addressing corrosive aspects of culture.

- Greater consideration of systemic causes when faced with evidence of employee misconduct.

- Designing compliance monitoring mechanisms that are robust and not artificially constrained, and reporting on the thresholds used in monitoring activities.

- Taking a broader approach to risk and consumer harm by considering potential reputational repercussions and impacts on consumer confidence and trust.

- Implementing measures to ensure clear and accurate communications with the Board, as well as with examiners and other regulators.

- Strengthening the audit function’s ability to serve as an objective check and to substantively analyze red flags and root causes.

We look forward to providing additional updates on this topic.

* * *

Endnotes

1OCC Issues Notice of Charges Against Five Former Senior Wells Fargo Bank Executives, Announces Settlements With Others (January 23, 2020), https://www.occ.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2020/nr-occ-2020-6.html; Notice of Charges In the Matter of Carrie Tolstedt, et al., https://www.occ.gov/static/enforcement-actions/eaN20-001.pdf.(go back)

2OCC Consent Order In the Matter of John Stumpf, https://www.occ.gov/static/enforcement-actions/ea2020-004.pdf.(go back)

3These figures are based on data available on the OCC’s website. Note that the OCC has imposed several restitution orders against individuals in the millions of dollars, with the highest being $9,415,819. Also, the OCC has previously sought civil monetary penalties in the millions of dollars.(go back)

4OCC Issues Consent Order of Prohibition and $50,000 Civil Money Penalty Against Former General Counsel of Rabobank N.A. (July 23, 2019), https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/news-releases/2019/nr-occ-2019-82.html.(go back)

5See Paul, Weiss Client Memorandum, “Lessons Learned from the Wells Fargo Sales Practices Investigation Report” (April 18, 2017), https://www.paulweiss.com/practices/litigation/litigation/publications/lessons-learned-from-the-wells-fargo-sales-practices-investigation-report?id=24208; Paul, Weiss Client Memorandum, “Implications of the Federal Reserve’s Enforcement Action Against Wells Fargo” (February 12, 2018), https://www.paulweiss.com/media/3977616/12feb18-wells-fargo.pdf; Paul, Weiss Client Memorandum, “The OCC Issues ‘Lessons Learned’ Review of Its Supervision of Sales Practices at Wells Fargo” (April 21, 2017), https://www.paulweiss.com/practices/litigation/litigation/publications/the-occ-issues-lessons-learned-review-of-its-supervision-of-sales-practices-at-wells-fargo?id=24224. For additional risk-mitigation considerations in the financial institutions context, see Paul, Weiss Client Memorandum, “Increasing Regulatory Focus on Reforming Financial Institution Culture and Addressing Employee Misconduct Risk” (February 21, 2018), https://www.paulweiss.com/media/3977629/21feb18-bank-culture.pdf.(go back)

Print

Print