Peter Reilly is Senior Director, Corporate Governance at FTI Consulting and Aniel Mahabier is CEO of CGLytics. This post is based on a joint FTI Consulting and CGLytics paper authored by Mr. Reilly based on data from CGLytics, with contributions from Jonathan Neilan, Melanie Farrell of FTI Consulting and Michael Murgatroyd of CGLytics.

Executive Summary

Ever since the financial crisis of 2008, the level of scrutiny on Boards of Directors and companies has grown, with the focus on corporate governance becoming particularly pronounced over the past five years. The 2018 iteration of the new UK Code included a number of substantive changes.

The growing capabilities of institutional investors and the broadening of the definition of governance from the Financial Reporting Council has dictated that 2019 was a year of significant change in a number of key areas.

FTI and CGLytics conducted an analysis of key areas of the new UK Code to determine the extent of that impact on UK and Irish companies. While the embedding of workforce engagement practices and disclosure has been subject to slower developments, guidance on pensions and Chair tenure have immediately influenced company and investor thinking—the result of which has been significant reductions in pensions for executive Directors in the FTSE and a sharp drop in average Chair tenure on both the FTSE and the ISEQ. However, despite the extent of change among Chairs, the level of gender diversity in those positions remains very low. The paper also includes wider potential risks for companies as the 2020 AGM season approaches.

Pensions: A Shift in Practice

The impact a single line of regulation can have on corporate governance can be pronounced. In 2010, the genesis of what is now termed “overboarding” was created by the addition of a line to the UK Corporate Governance Code (the “UK Code”):

“All directors should be able to allocate sufficient time to the company to discharge their responsibilities effectively”

With the complexity and time commitments of corporate directorships growing rapidly, the guidelines of proxy advisors and institutions have progressively tightened since 2010. By 2016, the external mandates of Directors were under intense scrutiny; by the 2017 and 2018 proxy seasons, a host of companies experienced dissent at AGMs due to concerns regarding the time commitments of those same Directors. The Financial Reporting Council (‘FRC’) had set the principle in 2010 and, over time, investors had acted to interpret it and its implications for Directors and their oversight of companies.

In 2018, a revamp of the UK Code meant that a similar phenomenon occurred but at a much more rapid pace. The 2018 revision to the UK Code included a number of substantive changes, aimed at “broadening the definition of governance” and emphasised the importance of interactions with stakeholders, clarity of purpose, high quality Board composition with a focus on diversity, and remuneration which is proportionate and supports long-term success. The last of those aims led to the inclusion of Provision 38, which states that:

The pension contribution rates for executive directors, or payments in lieu, should be aligned with those available to the workforce.

Over a number of years, there has been growing scrutiny on the level of pension contributions for executive directors of FTSE and ISEQ companies, with critics arguing such payments merely represent salary “top ups”. In February 2019, less than two months after the 2018 UK Code came into effect, the Investment Association (“IA”), the trade association for asset managers in the UK (and representing £5 trillion of AUM) published revised guidelines on pensions, which outlined a number of scenarios under which it would assign “Amber” or “Red” top ratings indicating matters of concern for investors:

Red Top: For companies with year-ends on or after 31 December 2018, any new remuneration policy that does not explicitly state that any new executive director appointee will have their pension contribution set in line with the majority of the workforce will receive a red top on the remuneration policy.

Red Top: Any new executive director appointee from 1 March 2019 whose pension contribution is above the level of the majority of the workforce will result in a red top on the remuneration report.

Amber Top: Any existing executive director receiving a pension contribution of 25% of salary or more will be amber topped on the remuneration policy and remuneration report.

The introduction of revised guidelines by the IA accelerated the focus on pension rates by investors and proxy advisors; significantly more so than had been the case following the introduction of the “overboarding” principle in 2010. Led by the IA’s asset manager members, it reflects the heightened focus from investors and proxy advisors on executive remuneration in recent years. More broadly, it demonstrates the consistent pattern of investment firms growing their governance team capabilities and applying greater scrutiny to corporate governance and remuneration at listed companies.

In response to the IA’s guidelines, Remuneration Committees have, reasonably, pointed to the difficulties in renegotiating contractual entitlements for existing Directors. For the most part, Committees took the logical step to commit to ensuring all pensions contributions for future executives would be reduced to the level available to the workforce.

Clearly, it is easier to set such a contribution from the outset as opposed to reducing existing entitlements. However, following on the back of the guidance issued in February—and potentially emboldened by the pace of change at public companies—the IA raised the bar again in September 2019, issuing updated guidance:

Amber Top: Any company with an existing director who has a pension contribution 25% of salary or more, as long as they have set out a credible plan to reduce that pension to the level of the majority of the workforce by the end of 2022.

Red Top: Any company with an existing director who has a pension contribution 25% of salary or more, and has not set out a credible plan to reduce that contribution to the level of the majority of the workforce by the end of 2022.

Red Top: Any company who appoints a new executive director or a director changes role with a pension contribution out of line with the majority of the workforce, or seeks approval for a new remuneration policy which does not explicitly state that any new director will have their pension contribution set in line with the majority of the workforce.

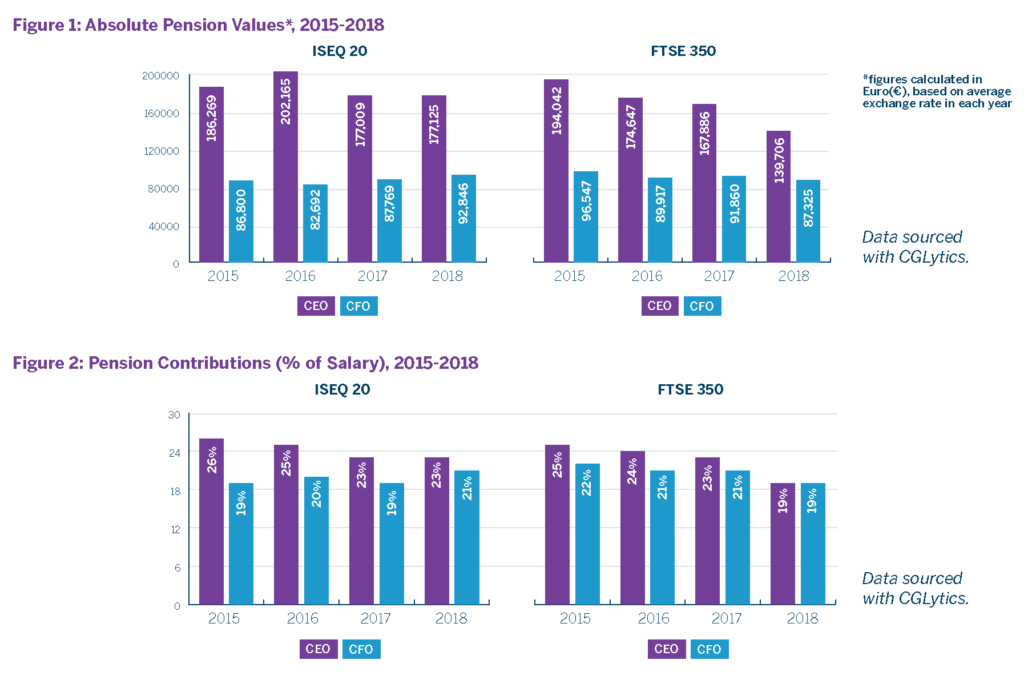

This guidance by the IA means that by 2022—regardless of when they started employment—all executive directors should receive pension contributions aligned with those of the workforce. The updated UK Code published in July 2018, together with the stance of the IA, has already had a marked impact on pension contributions. While the pressure has grown considerably on companies in 2019—acting as a catalyst for change—CGLytics data has found a downward trend in pensions in Ireland since 2016 and an even sharper fall in the UK since 2015:

Despite the fall in pension levels for Executive Directors, a majority of companies have not yet aligned executive pensions with those of the wider workforce. With average pensions sitting at a level considerably below 19% for UK employees, it appears at least 80% of FTSE 350 and ISEQ 20 companies may have to consider whether to include a “credible plan” to reduce executive pensions prior to the end of 2022 in this year’s Annual Report. More specifically, CGLytics data indicates that, based on 2018 Annual Reports, approximately 15% of CEOs are in line for a “red top” from the Investment Association in the event that no such “credible plan” is offered. Those that fail to provide such disclosure are likely to experience a level of dissent at their 2020 AGMs, with that level of dissent rising commensurately as pension levels increase. This does present a challenge for Remuneration Committees. The unwinding of contractual obligations can be difficult and no two situations are alike—pension contributions can reflect the age of a CEO on appointment; their distance in years from retirement age; and relate to other elements of their overall remuneration package. However, it is an issue which will have to be addressed in some form during the period ahead as investors and proxy advisors have already laid down a marker in terms of voting patterns at AGMs held early in 2020 and this trend is likely to continue for the remainder of the AGM season.

Chair Tenure: A Change of Tack

In addition to concerns regarding the level of pension payments, investors and proxy advisors are in the process of embedding revised guidelines on the tenure of Chairs. The impact of tenure on independence has long been an issue of debate between companies, proxy advisors and investors. At some point, most FTSE350 and ISEQ 20 companies will have been subject to scrutiny around a Director’s loss of independence after nine years in the role. The issue of tenure has now been extended to the Chair and as part of the FRC’s focus on “high quality Board composition with a focus on diversity”, the following provision was included in the 2018 iteration of the UK Code:

The chair should not remain in post beyond nine years from the date of their first appointment to the board. To facilitate effective succession planning and the development of a diverse board, this period can be extended for a limited time, particularly in those cases where the chair was an existing non-executive director on appointment. A clear explanation should be provided.

Given the differing opinions on when a Director’s tenure becomes a concern, particularly for Chairs who are leading the Board, the reaction and pressure on companies has not been as stark as in the sphere of pensions. Indeed, the rigidity of the revised rule of generally limiting Chair tenure to nine years has faced a level of criticism, which has focused on the “disruption” that the rule could cause. With pressure on companies to consistently ensure a majority independent Board and having to sometimes “exit” longer standing, experienced Directors to maintain that ratio, there may have been a level of comfort in having a longer-tenure Chair to provide a degree to consistency of oversight and understanding of a business evolution. That is not to say there is no benefit in refreshment of a Chair, just that having an individual who has helped navigate companies through periods of growth, turbulence or management change can provide reassurance to the market.

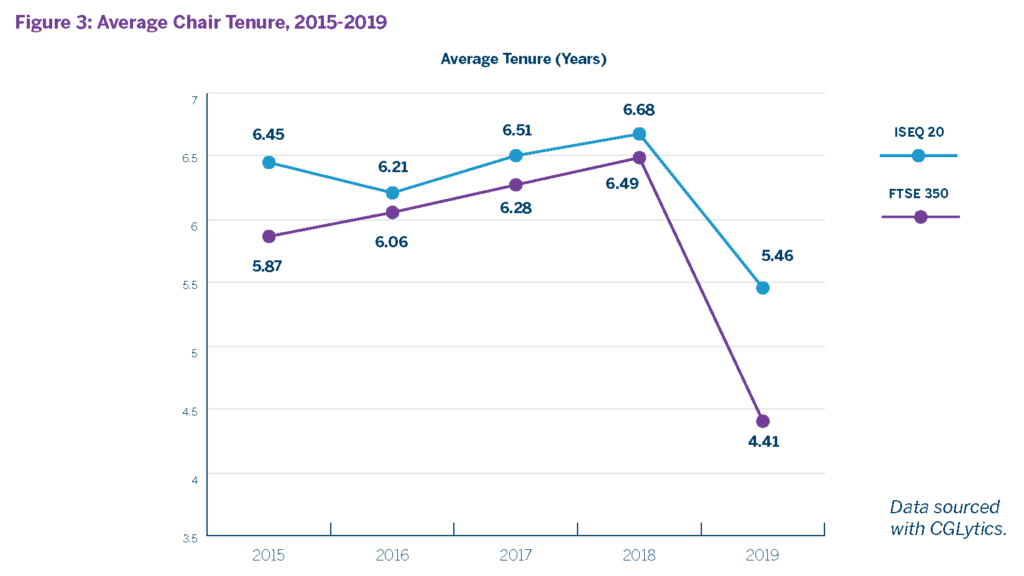

Nonetheless, there has been a series of resignations from FTSE 350 and ISEQ 20 companies over the past 18 months, as well as instances where Chairs have committed to stepping down at a designated date in the future. CGLytics data shows how the changes have already impacted average tenure at FTSE 350 and ISEQ 20 Boards:

With average CEO tenure for UK companies remaining low and Boards coming under pressure to ensure Chairs limit their tenure, there appears to be credence to the idea that the new provision may be excessively disruptive. However, what critics of the provision may be missing is that it is designed to be just that—disruptive to the absence of diversity in the position of Board Chairs. The extent of change already at the head of Boards may also point to another issue, the unwillingness of companies to embrace “comply or explain”, and provide investors with clear reasons for extending a Chair’s tenure.

Diversity

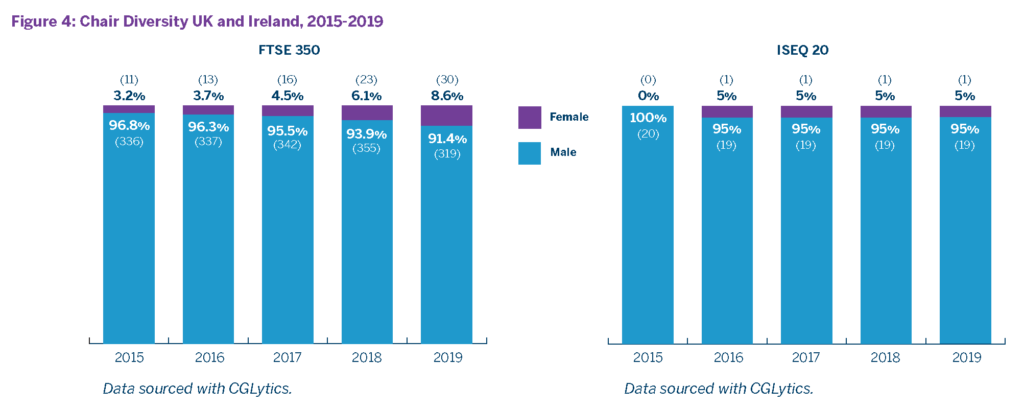

UK companies have pointed to the progress made in enhancing diversity at Board-level, with 33% of Directors in the FTSE 100 now female, meeting one of the targets of the Hampton Alexander Review ahead of the deadline of the end of 2020. While this is certainly progress, some have argued that it is largely low hanging fruit, with developing diversity in senior leadership positions the more meaningful of challenges. Only 7% of FTSE100 CEOs are female and that drops to 2% in the FTSE 250. The equivalent statistic for the ISEQ 20 is 15%.

While focusing on the potential for disruption at the top of UK and Irish companies, one clear aim of the 2018 Code is just that—disrupting what is viewed as Board structures that are impeding diversity. In setting out the potential reasons for “exemptions” from the rule, the FRC states support of “the company’s succession plan and diversity policy” as a potential reason. The FRC has usually eschewed such rigidity in terms of guidance on the length of service of any Director; however, the implementation of this provision is explicit recognition that the pace of change in terms of leadership positions at companies has been too slow. If companies are too slow to change, the FRC has showed a willingness to intervene in an effort to force it. Much like executive leadership positions, there was obviously a clear sense that there continues to be a lack of diversity in those Directors tasked with leading the Board: the Chair.

As Boards are forced to seek more regular change at the head of the Board, and appointments to the Board are increasingly female, the FRC clearly hopes this somewhat rigid change will act as a catalyst for much quicker change at the top of UK and Irish companies. Only last week, RBC Global Asset Management indicated that it would be voting against all members of Nomination Committees where women made up less than a quarter of Board seats while Columbia Threadneedle announced that it was widening its focus, targeting companies with a lack of women in senior leadership positions.

Explanations

As the FRC included in the preamble to the 2018 iteration of the UK Code, “Explanations are a positive opportunity to communicate, not an onerous obligation”. Consequently, if companies believe that their approach to governance represents less risk than that which is advocated by the UK Code, such steps should be embraced and extensively detailed in Annual Reports. Companies will argue that investors and proxy advisors may be less forgiving—particularly when evaluating hundreds of companies a week during AGM season—however, when issuing the 2018 Code, the FRC has laid out the challenge to both of those parties, asking that explanations are not evaluated in a “mechanistic” way.

In response, those companies that have Chairs in situ for nine years or more have the opportunity to explain the importance of the Chair continuing in position. While the standard of explanations will naturally be expected to rise in line with the tenure of the Chair, given the level of flexibility that has been espoused by proxy advisors and individual investors on this issue, there is likely greater latitude for companies here than other provisions. In addition to effective and specific disclosure, strong communication and meaningful engagement with major investors is likely to mitigate the risk of large votes against.

2020 AGM Season: What to Expect

Outside of pressure to reduce pensions and enhance succession plans for Chairs, the new UK Code sets out the expectation that Boards put in place robust channels for engagement with the workforce; implement shareholding guidelines that remain in place for a period after the departure of an executive; and, ensure that all long-term incentive plan awards are subject to performance and vesting restrictions of at least five years.

Workforce Engagement

On workforce engagement, we have observed a preference from UK and Irish companies to designate a Director as responsible for workforce engagement, with certain notable exceptions.

Case Study: Capita PLC

Employees manage thousands of processes and control the vast majority of companies’ business relationships. Their views can be hugely informative to a Board in terms of operational effectiveness and strategy development; and, their commitment to a company can uncover business risks at an early stage.

In May 2019, Capita plc became only the second UK plc to appoint a Director to their Board in 30 years. In announcing the decision, Capita’s head of HR stated:

“We’re about to become the largest business in three decades to appoint employees as non-executive directors—and I hope other HR leaders will follow suit.”

The decision at Capita came on the back of the discussion of placing workers on Boards for a number of years. Initially, the idea was given oxygen by Theresa May, who in a speech not only advocated putting a worker representative on Boards, but also consumer representatives.

While those goals became slightly watered down in the 2018 Code, which includes appointing a worker director as one of three options, the overarching aim of amplifying the voice of employees in the Board room has remained.

Engaged employees are those fully invested in their firm and their work. They are the ones who actively think about the firm’s processes—and identify improvements. Their enthusiasm reflects a corporate culture that encourages engagement. Most importantly, they are productive. Conversely, disengaged workers can be a negative drag on productivity and value creation, but are also a risk which can permeate throughout the organisation. Through direct engagement, Boards can obtain insights into the evolution of corporate culture they cannot get anywhere else.

Given that a majority of companies will only be reporting on which avenue they have taken in advance of the 2020 AGM season, it remains to be seen whether any more opt for the “radical” approach of appointing a worker Director. In terms of voting patterns, investors will expect movement in this area without necessarily demanding extensive evidence of improvements in interactions between Boards and the general workforce.

Nonetheless, as details of engagement mechanisms are set out by companies in 2020, those expectations are likely to ramp up again for future years. We will be reviewing disclosures as they are released and provide an in-depth review during the summer.

Remuneration Policies

In contrast to steps to enhance workforce engagement, with the majority of UK companies set to seek shareholder approval of remuneration policies in 2020, failure to implement the two structural aspects for pay structures outlined above is likely to negatively impact voting. As with other areas of corporate governance and executive remuneration, being identified as an outlier is the clearest way to heighten scrutiny at AGM time. Given that the significant majority of FTSE 350 companies have now put in place a vesting/holding period of five years, failure to do so is likely to increase opposition to remuneration policies. Likewise, the inclusion of post-employment shareholding guidelines is becoming commonplace and has been referenced in a number of updated proxy voting guidelines, dictating that those companies without such guidelines will need to go the extra mile in terms of disclosure. Specifically, the 2018 UK Code expects a formal policy to be put in place:

“The remuneration committee should develop a formal policy for post-employment shareholding requirements encompassing both unvested and vested shares.”

Those that have argued that the structure of their incentive plans ensures executives will hold shares after departure have met resistance—investors and proxy advisors pointing out that such requirements would be based on variable remuneration, meaning that if there are no pay-outs under incentive schemes, there would be no formal requirement to hold shares.

Restricted Shares—a Tipping Point?

One area that has garnered significant attention over the past four years that was not addressed in the 2018 UK Code is the argument in favour of Restricted Shares. Since the publication of the Executive Remuneration Working Group Final Report in July 2016, adoption of Restricted Share Plans has been slow. Potentially fearing a rebuke from shareholders and proxy advisors, as well as the experience of companies that attempted to introduce hybrid performance and Restricted Share plans, only a handful of companies have proposed the removal of performance conditions from long-term incentive plans.

Table 1: Restricted Shares—Shareholder Approval

| Company Name | Restrictred Shares

Approved |

ISS Recommendation | GL Recommendation | Shareholder

Voting |

Current Market Cap (€m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pets at Home | July, 2017 | Against | For | 85% | 1420 |

| Kenmare Resources | May, 2017 | For | For | 92% | 260 |

| Weir Group | April, 2018 | For | For | 92% | 3460 |

| Card Factory | May, 2018 | Against | For | 84% | 274 |

| Whitbread | December, 2019 | Against | For | 70% | 5680 |

Source: company announcements and Annual Reports

However, in addition to the companies cited above, it was recently reported that Lloyds is considering the introduction of a Restricted Share Plan as part of their remuneration policy to be proposed later this year. Lloyds would be, by far, the largest company to introduce a Restricted Share Plan in the UK and Ireland and their proposal act as a catalyst for spurring change to incentive frameworks at public companies. So long as the schemes include a reduction in maximum potential pay and vesting restrictions of at least five years, it would appear that majority support is likely to be received, with the variance in how far that hurdle is cleared linked to quantum, holding periods and performance underpins.

ESG & Proxy Voting

Given the level of capital flowing into ESG-related investment strategies and funds, as well as the focus on the topic from media and wider stakeholders, it is unsurprising that 2020 marks the year that ESG standards begin to impact proxy voting. In January 2020, State Street (“SSGA”), the world’s third largest asset manager, set out a statement that it will begin to vote against Directors at companies that lag behind peers on its self-generated ESG tool—a “responsibility factor,” or R-Factor. The tool rates companies on various ESG metrics and beginning this year, SSGA will begin voting against board members at Japanese, US, UK, Australian, German and French companies that lag behind their peers on their R-Factor Score. SSGA will first focus on companies that rank particularly poorly in ESG performance but, from 2022, will start using proxy voting against Board members of all companies that are underperforming on ESG scoring to influence change.

While this will have the most pronounced impact on companies where SSGA has a large holding, it is the start of a wider trend. Investors use proxy voting as a means to register displeasure with how a company is being run—in terms of risk, strategy and disclosure—and ESG plays a role in all three.

Overboarding

As outlined, over the past decade, the issue of “overboarding” has risen to the fore of investors concerns and associated proxy voting. In light of the significant level of shareholder opposition in 2018, the instances of proxy voting for this issue fell in 2019, largely due to a reduction in mandates by those deemed to be “overboarded”. Nonetheless, proxy voting guidelines and investor approaches on this issue continue to evolve, and all external mandates will be subject to intense scrutiny from investors and proxy advisors. Set out below is an overview of the approaches of three of the largest asset managers in the UK, which are indicative of wider market views on what constitutes a reasonable number of external mandates.

| Investor | 2020 Proxy Voting Guidelines |

|---|---|

| BlackRock | BlackRock may vote against the election of an outside executive as the chairman of the board as we expect the chairman to have more time availability than other non-executive board members.

Likewise, we believe it is a good practice for the lead independent director not to be an outside executive given the time commitment of both roles, and may vote against the (re)election of an outside executive as a non-executive director if they are newly appointed to the role of lead independent director. |

| Vanguard | A fund will generally vote against any director who is a named executive officer (NEO) and sits on more than one outside public board. In this instance, it will typically vote against the nominee at each company where he/she serves as a nonexecutive director, but not at the company where he/she serves as an NEO.

A fund will also generally vote against any director who serves on five or more public company boards. In that instance, the fund will typically vote against the director at each of these companies except the one where he/she serves as chair or lead independent director of the board. |

| Legal & General | We expect non-executive directors not to hold more than five roles in total. We consider a board chair role to count as two directorships due to the extra complexity, oversight and time commitment of this role. A practising executive director should not hold more than one non-executive director role within an unrelated listed company. |

Source: company announcements and Annual Reports

Originally limited by total mandates, investors now include more nuance in their guidelines, differentiating between the scope of roles and, in Blackrock’s case, extending the focus to Senior Independent Directors. Given the ever-expanding roles and responsibilities of Chairs with each iteration of the Code, guidelines on Chairs’ external commitments may become almost as restrictive as those which apply to executives.

With CGLytics data pointing to almost 20% of FTSE 350 and ISEQ 20 Chairs currently holding more than two external Directorships, there may be a number who find themselves in the firing line over the coming months.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print