Aaron Atkinson is a partner and Mathieu Taschereau and Shane Freedman are associates at Davies Ward Phillips & Vineberg LLP. This post is based on their Davies memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Case Against Board Veto in Corporate Takeovers by Lucian Bebchuk.

With much of the world focused on the immediacy of the COVID-19 pandemic, including its heavy human and economic toll, we have cast our eyes optimistically on the (near, we hope) future when companies regain sufficient confidence to re-enter the public M&A market in large numbers. Although attention has largely centred on businesses that are in a struggle for survival, certain businesses will emerge stronger owing to factors such as shifts in consumer needs and preferences or more durable balance sheets. As a result, the post-pandemic corporate landscape may be ripe for consolidation, with relatively larger and better-capitalized issuers seizing the opportunity to acquire their weakened competitors. It is also possible that in certain capital-intensive industries, such as mining, competitors may be more inclined to cast aside their differences and consolidate their balance sheets, a trend that is already showing some momentum.

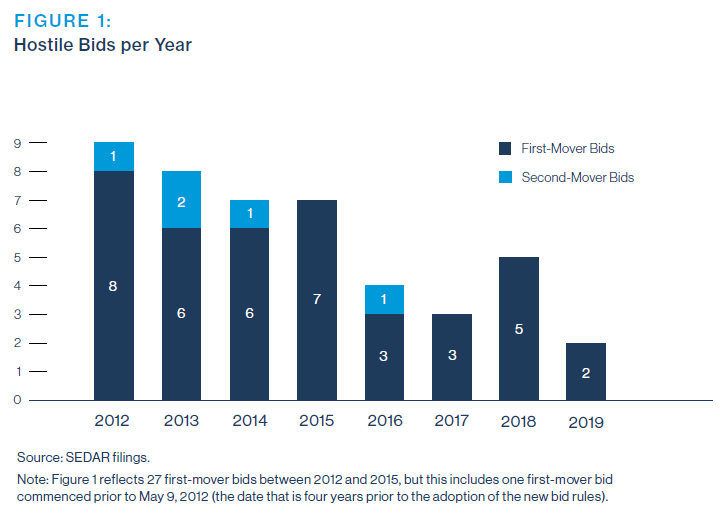

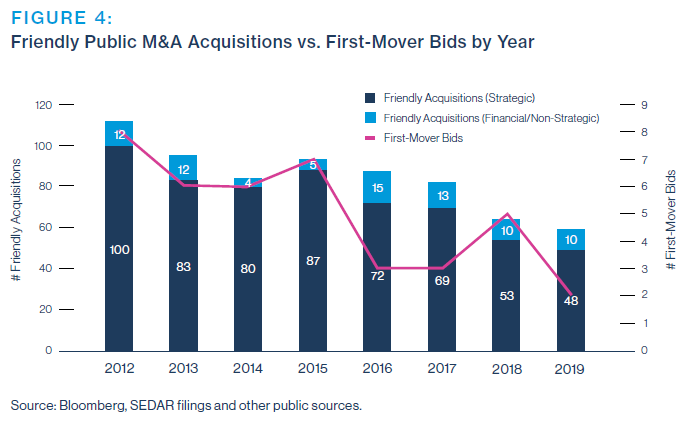

We will be tracking activity levels to assess whether the foregoing theories prove correct; however, our analysis of Canadian public M&A activity (both friendly and hostile) from 2012 to the end of 2019 suggests that expectations of significant consolidation activity should be tempered, at least insofar as it involves acquisitions of Canadian-listed issuers. In particular, we found that hostile bids declined by 50% after May 9, 2016, the date on which Canadian securities regulators implemented fundamental changes to the takeover bid rules, which were designed to “rebalance” the prevailing bid dynamics and place more power in the hands of target boards.[1] Digging deeper into the data, we found that financial buyers—who would already be expected to shy away from the potentially significant costs and uncertainty of launching a hostile bid—vacated the field entirely after the new rules were adopted. As a result, every hostile bid under the new regime has been commenced by a strategic purchaser. We found a similar downward trend in friendly acquisitions of Canadian-listed issuers, with such transactions declining by 24% in the same four-year period. In fact, this statistic masks a more significant 30% decline in the number of friendly acquisitions by strategic purchasers since the start of 2016.

It is unclear whether the decline in friendly acquisitions by strategic purchasers, whose only alternative to acquiring a Canadian-listed issuer in a negotiated transaction is to launch a hostile bid, is linked to a bidder’s relatively weaker hand under the new takeover bid regime. However, the correlation is relevant when assessing whether post-pandemic public M&A in Canada will remain tepid by historical standards. On the one hand, the entire eight-year study period experienced strong growth in global M&A volumes with macroeconomic conditions generally conducive to acquisition activity and its attendant risk-taking—all of which suggests that the downward trend in acquisitions of Canadian-listed issuers was an outlier and conceivably driven in part by the new regime. On the other hand, the decline might also be explained by industry-specific dynamics: the Canadian mining and energy sectors, both of which account for a significant portion of Canadian-listed issuers and M&A volume, have experienced turbulence since 2016. Not surprisingly, deal-making in both sectors underwent a steep decline in the latter half of our study.

With the foregoing in mind, it is possible that a post-pandemic landscape in which the weak are more starkly divided from the strong could be sufficient to entice otherwise reluctant purchasers to aggressively pressure target boards who, in turn, might be more inclined to cut a deal to placate restive shareholders, creditors and employees regardless of any theoretical bargaining power handed to them under the new rules. At the same time, macroeconomic conditions are likely to remain volatile for some time, which could have the opposite effect, causing prospective purchasers to prioritize protecting their own long-term prospects before pulling the trigger on an aggressive acquisition strategy that could consume months of management’s time and resources in pursuit of a decidedly uncertain outcome.

We plan to release a more in-depth review of our research findings in the coming months, but offer this preliminary analysis to mark the four-year anniversary of the new bid rules and to provide a framework to analyze the Canadian public M&A landscape as we emerge from the pandemic. We will continue to monitor activity and look forward to sharing more of our insights.

The results of our research to date can be distilled into four key findings, which we discuss in greater detail later in this post.

Trends in Canadian Public M&A Since 2016

Key Findings

- First-mover hostile bids for control of Canadian-listed issuers have declined by 50% since the adoption of the new takeover bid rules compared with the preceding four-year period, with an even more pronounced decline in bids for small cap issuers.

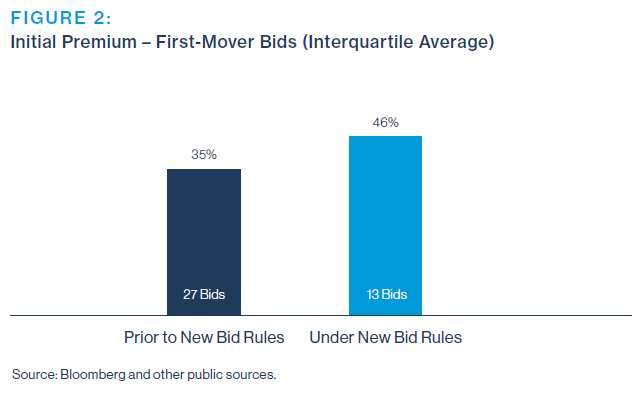

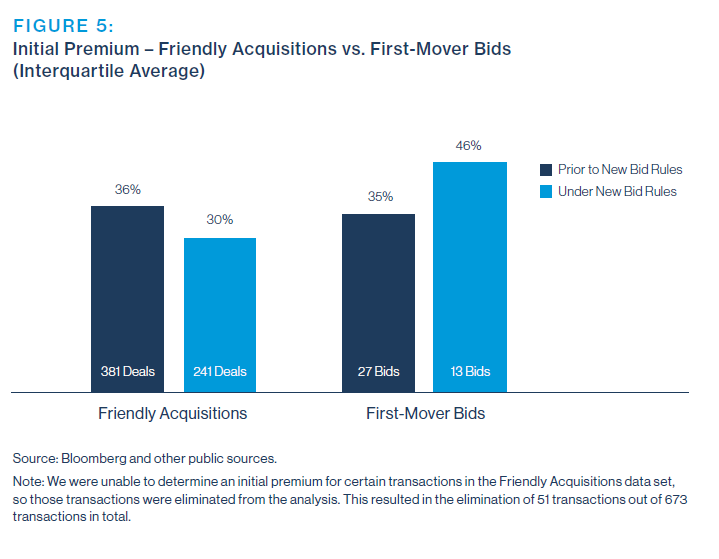

- The average premium for a first-mover hostile bid increased by over 30%, and bidders had better odds of success than in the prior period.

- Friendly acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers declined by 24% in the four-year period ended in 2019, with the number of acquisitions by strategic purchasers declining by more than 30%.

- The average premium for friendly acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers has declined by approximately 16% since the adoption of the new takeover bid rules.

Overview of the 2016 Changes to the Canadian Bid Regime

Our empirical analysis over the eight years from 2012 to the end of 2019 shows that Canadian public M&A activity has been on a downward trend since 2016, the year in which fundamental changes to the Canadian takeover bid regime were introduced to address concerns that that the rules favoured bidders over target boards. [2] Notably, these concerns took on added urgency around the time of the last financial crisis, which may have been a catalyst for the broad-based support required to ultimately implement the changes.

One of the principal purposes of the new bid regime was to “rebalance” the prevailing bid dynamics and place more power in the hands of target boards. The 2016 regime included three key amendments:

- the minimum bid period for a first-mover bid tripled from 35 to 105 days, which the target board can reduce to as few as 35 days (with the timing of a second-mover bid dictated by the timing of the first-mover transaction);

- all bids are subject to a mandatory minimum tender condition requiring that a majority of the shares not owned by the bidder and its allies must be tendered before any shares can be taken up; and

- if all bid conditions are satisfied, the bidder must extend the bid by an additional 10 days to allow shareholders additional time to tender.

The leverage afforded to the target board through its control over the duration of the bid and the significantly increased time to seek alternatives, coupled with the mandatory minimum tender condition, was expected to increase the incentive for bidders to negotiate with the target board and increase boards’ ability to “negotiate better quality friendly bids.”

Trends in Canadian Public M&A Since 2016

1. First-mover hostile bids for control of Canadian-listed issuers have declined by 50% since the adoption of the new takeover bid rules compared with the preceding four-year period, with an even more pronounced decline in bids for small cap issuers.

The classic hostile bid is a so-called first-mover bid made directly to shareholders of a target company, putting control of the company “in play.” In doing so, the bidder seeks to sidestep negotiation with the target board and use its first-mover advantage to control the narrative and catch potential competitors off guard and out of time. One might expect that first-mover bidders would think twice about launching a bid under the new regime, given that the historical timing advantage of being a first mover, among others, has been effectively eliminated. A first-mover bid can be contrasted with a “second-mover” bid—one in which a bidder, seeking to jump into the fray of a public auction, uses a hostile bid to try to break up an existing friendly transaction. We would not have expected second-mover bids, which were relatively rare historically, to be significantly affected by the new rules since the timing of the initial friendly transaction dictates the timing of the second-mover bid.

Between May 9, 2016, the date on which the new bid rules came into force, and December 31, 2019, there were only 13 first-mover hostile bids for control of Canadian-listed issuers, a 50% decline from the 26 first-mover hostile bids in the period between May 9, 2012, and May 8, 2016. Even second-mover bids declined, although only four such bids were launched in the prior period, decreasing to one in the later period. The mining and energy sectors had the greatest level of activity under the new rules, accounting for 75% of all hostile bids since 2016. Although not reflected in Figure 1, the decline in bids for small cap issuers was particularly pronounced—companies having a market capitalization of $50 million or less were targeted only five times by a first-mover bid, compared with 15 in the prior period, a decrease of two-thirds.

Under the new regime, the hostile bid has been deployed as an acquisition strategy only by strategic purchasers. Financial purchasers who, generally speaking, would be expected to shy away from pursuing a hostile bid given the associated time and costs (not to mention the substantial uncertainty of success) have not launched a single hostile bid since the adoption of the new rules–after having launched eight in the prior period.

2. The average premium for a first-mover hostile bid increased by over 30%, and bidders had better odds of success than in the prior period.

Our analysis of premium data between the two periods shows an increase of more than 30% in the average initial premium offered by first-mover bidders, with the average initial premium increasing to 46%, from 35%. As discussed in more detail below, this increase contrasts with a 16% decrease in the average premium for friendly acquisitions compared with the prior period. Although the increase in the average premium for first-mover bids is based on a very limited data set, factors such as the longer period during which the bid is exposed to competition and defensive action by the target may have driven hostile bidders to ante up more to target shareholders than under the previous regime. The higher average premium might also be explained in part by the fact that all of the first-mover bids under the new regime were initiated by strategic purchasers, who would generally be expected to offer a higher premium than financial purchasers, given the added strategic value and synergies that are more likely to accrue from a successful acquisition.

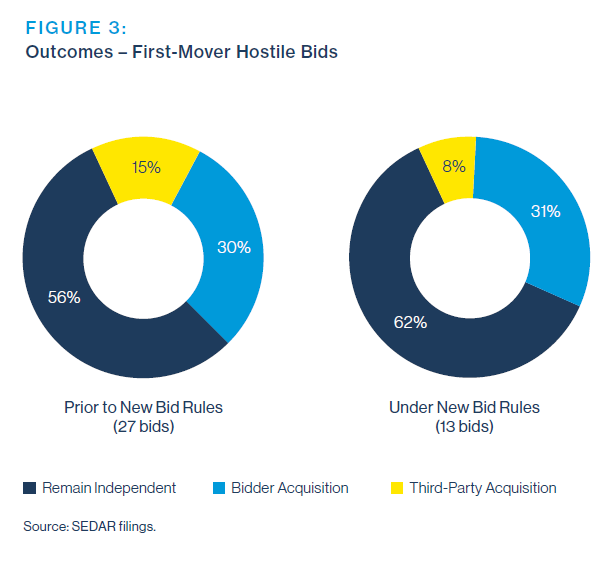

However, the sizable increase in average premium did not drive a proportionately better outcome for the hostile bidder. Of the 13 first-mover bids that were launched under the new rules, outcomes were largely in line with outcomes in the prior period, with bidders acquiring control more often in the period under the new rules (62% vs. 56%), while issuers remained independent about 30% of the time during the entire study period.

3. Friendly acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers declined by 24% in the four-year period ended in 2019, with the number of acquisitions by strategic purchasers declining by more than 30%.

We found a similar, although not as substantial, downward trend in the number of “friendly” acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers, with the number of such transactions declining by approximately 24% when compared with the four-year period ended in 2019; however, the period since 2016 reveals two opposite trend lines when we separate transactions by strategic purchasers from those by financial purchasers.

Although financial purchasers appear to have shunned hostile bids under the new regime, our data reveal that the number of friendly acquisitions by financial purchasers actually increased by more than 45% in the four years ended in 2019. In contrast, similar to the hostile bid trend line, friendly change of control transactions involving a strategic purchaser declined by more than 30% in the four years ended in 2019. There are likely several explanations for the decline, including volatility in key sectors such as mining and energy. It is also possible that the decrease was driven at least in part by a view that hostile bids are now a less viable alternative for purchasers than a negotiated transaction, with boards similarly viewing a hostile bid as less of a threat and therefore driving a harder bargain in friendly negotiations. To the extent that this dynamic played out, one might also expect the data to reveal a higher average premium in friendly transactions that were completed, but, as discussed further below, our research reveals the opposite trend.

Consistent with our findings on first-mover bids, the segment of the market experiencing the greatest decline in activity involved issuers with a market capitalization of $50 million or less—the number of acquisitions of companies of this size declined by almost 50%. Although the number of companies listed on the TSXV has decreased by over 25% since 2012, this reduction in “supply” alone does not explain the decline.

The mining and energy sectors also experienced disproportionately lower activity when compared with other industries. Prior to the new bid regime, acquisitions of issuers in the energy and mining sectors represented 70% of all friendly public M&A acquisitions (and 72% of all transactions involving strategic purchasers), whereas in the four-year period ended in 2019, they represented only 54% (and 58% of all transactions involving strategic purchasers).

4. The average premium for friendly acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers has declined by approximately 16% since the adoption of the new takeover bid rules.

Although hostile bidders in first-mover bids offered a higher average premium under the new regime, we witnessed the opposite trend in friendly acquisitions of control of Canadian-listed issuers. In particular, the average premium in these friendly transactions decreased from 36% in the period from January 1, 2012, to May 8, 2016 (37% for transactions by strategic purchasers) to 30% in the period from May 9, 2016, to the end of 2019 (31% for transactions by strategic purchasers), a decline of approximately 16%. One might have expected that the average premium would increase if purchasers, seeking to avoid the time and cost of launching a hostile bid, felt the need to pay more to win the target board’s endorsement. At the same time, it is also possible that other factors, such as loftier market valuations in some sectors or volatile commodity prices in other sectors, contributed in some measure to both the decrease in friendly transactions and the average premium. Another possible theory could be that, given the additional leverage afforded to the target, purchasers felt compelled to offer greater value to insiders at the expense of shareholders in an effort to gain the endorsement of the target board and management team. We have not examined this theory, but it would be an interesting area for further study.

What Caused the Decline in Canadian Public M&A Activity?

Our research was not designed to prove causation between the adoption of the new bid rules and the level of Canadian public M&A activity. One could argue that the initial data show some correlation, but it is unclear whether the level of hostile bid activity follows general public M&A trends or drives them. It is clear that Canadian public M&A activity since 2016 has run counter to the global trend of increasing M&A volumes; however, trends specific to industries such as mining and energy, which make up a sizable volume of Canadian-listed issuers, could equally explain the decline. Regardless of the exact causes, it is clear that even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the landscape for Canadian public M&A had changed—for some companies, a hostile bid might now be viewed as less of a threat and, for potential purchasers, particularly financial purchasers, an increasingly unattractive strategic option.

Looking Ahead

If Canadian public M&A activity is to rebound post-pandemic, one catalyst may be a shift in the relative leverage of target boards in favour of prospective purchasers, given the numerous potential external pressures faced by target boards whose companies are most adversely affected by the pandemic. However, prospective purchasers will need to be reasonably confident of their own long-term viability in an economic environment that is expected to be unsettled for some time.

In particular, shareholders in weakened companies might be more receptive to any liquidity event over insolvency. Creditors of these companies might also welcome consolidation to decrease their own exposure. And other stakeholders, such as employees, might also welcome an employer with a stronger balance sheet, betting that some layoffs as a result of transaction synergies are better than mass unemployment. Should such a dynamic play out, a potential purchaser might be more inclined to take (or credibly threaten to take) its offer directly to shareholders, despite the risks of doing so under the new bid regime, in the hope that target boards’ resolve to use their leverage will be weakened by these and other external pressures. Of course, prospective purchasers might instead bide their time if the pandemic, and the resulting economic uncertainty, continues—in which case a strengthened balance sheet would be viewed as providing shelter in the continuing storm rather than a potent weapon to be wielded on weakened competitors.

Our Methodology

Hostile Bid Data Set. We generated our data set of hostile bids by running a search on the System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval for every takeover bid circular filed between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2019. Our data set was then narrowed to include only those bids in which a purchaser sought to acquire legal control (being the ownership of a majority of voting securities) of a Canadian-listed company where such bid that was not supported by a recommendation from the target board at the time of announcement of the bid. We further refined the data set to eliminate three cross-conditional bids made by Zara Resources Inc. in 2013, which we viewed as outliers. In particular, these three bids were cease-traded for non-compliance with the applicable rules before the target boards were required to make a recommendation in a directors’ circular. Once this data set was complete, we classified bids according to the date of formal commencement of the bid.

Classifying Hostile Bids. Our principal focus was on first-mover bids given that the new bid rules primarily affect those bids more than others. In that regard, in the case of a bid launched as an alternative to an existing friendly transaction negotiated by the target, the timing of the bid is dictated by the timing of the existing friendly transaction. We characterized a “first-mover” bid as one in which a bidder commences a formal takeover bid for a target in the absence of any publicly announced material transaction requiring shareholder approval, which could include a friendly change of control transaction.

Characterizing Outcomes. We defined success of a bid by reference to whether a change of legal control occurred as a result of the bid. If a bidder acquires legal control of the target following the launch of the bid and prior to its expiry or withdrawal, or the bidder and target enter into a friendly transaction using an alternative transaction structure, that constitutes a “bidder acquisition.” If a third party other than the bidder acquires legal control of the target following launch of the bid and prior to its expiry or withdrawal, such as in a “white knight” scenario, that constitutes a “third-party acquisition.” If no party acquires legal control of the target following the launch of the bid and prior to its expiry or withdrawal, that constitutes “remain independent.”

Friendly Transaction Data Set. We generated our data set of friendly public M&A transactions by running a search on Bloomberg for all M&A transactions involving the acquisition of a Canadian-listed company between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2019. In order to compare the public M&A transaction data set with the hostile bid data set, we selected only those transactions involving the acquisition of legal control of the target. From this subset, where identifiable, we removed acquisitions in which the change of control arose as a result of an issuance of equity from treasury (such as private placements, reverse takeovers and qualifying transactions), transactions arising out of insolvency proceedings and private secondary market sales by a selling shareholder. We also removed transactions that were marked as “Terminated” or “Withdrawn” and removed certain transactions marked as “Pending” where the public record indicated that the transaction was terminated prior to completion.

Classification of Purchasers. The classification of purchasers as “strategic” or “financial” involves a degree of subjectivity in certain cases. To classify strategic purchasers versus financial purchasers, we compared the Bloomberg industry classification for purchasers and targets. Transactions in which the industry classification was the same for the target and the purchasers were classified as strategic transactions, except for transactions in which the industry classification for both bidder and target was “Financial.” Transactions in which either the Bloomberg industry classification differed between purchasers and targets or in which both the purchaser and target had the industry classification “Financial” were reviewed individually to determine the appropriate classification. For hostile bids, we classified bidders as “strategic” or “financial” in the exercise of our judgment on the basis of a variety of factors, including a review of the bidder’s disclosure and investment approach.

Premium Data and Calculations. To generate our premium data set, we relied principally on Bloomberg’s “Announced Premium” field. In certain cases, we supplemented the data with additional research and investigation of other sources, including news releases, takeover bid circulars and directors’ circulars where we believed that additional clarification or calculation was necessary due to perceived limitations in the data set generated by Bloomberg. For instance, in some cases Bloomberg did not report premium data or used an announcement date that differed from the announcement date indicated in our other research. In certain cases in our friendly public M&A transaction data set, we were unable to determine an initial premium, whether from Bloomberg or any other public source, so those transactions were eliminated from the data set for our premium analysis. This resulted in the elimination of 33 transactions for the period between January 1, 2012, and May 8, 2016, and 18 transactions for the period between May 9, 2016, and December 31, 2019. We analyzed average premium data by using interquartile averages. This allowed us to control for outliers in our data set of hostile bids and public M&A transactions. An interquartile range separates a data set into four quartiles of 25% of occurrences and then eliminates the first and last 25%, being the highest and lowest frequencies in a range, in order to produce a set of 50% of average occurrences. For our premium analysis of friendly public M&A transactions, we compared all available premium data for all transactions in our data set announced prior to May 8, 2016, against all available premium data for all transactions announced in our data set announced on or after May 9, 2016, meaning that we were comparing approximately 52 months of data against data for approximately 44 months.

Some Words of Caution

Our research, discussion and analysis should neither be construed as arguing for a causal relationship between any two variables analyzed nor be taken as legal advice or guidance. Although our analysis is intended to contribute to the discussion surrounding the changes to the Canadian takeover bid regime and the outlook for Canadian public M&A, we also caution that there are inherent limitations in drawing conclusions from our data sets. In particular, the relatively small number of hostile bids over the study period forms a fairly small data set, which limits the ability to draw meaningful statistical conclusions. In addition, a four-year period is a relatively short time frame in which to evaluate the lasting impact of changes as fundamental as those introduced in 2016. Notwithstanding the foregoing limitations, our analysis revealed some potential trends that we felt worthy of discussion and debate, and it is in that spirit that we have published this post.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of many students and staff, as well as the invaluable feedback from our colleagues, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Endnotes

1See National Instrument 62-104—Take-Over Bids and Issuer Bids: https://www.osc.gov.on.ca/ documents/en/Securities-Category6/ni_20160505_62-104_take-over-bids.pdf.(go back)

2The new bid rules became effective on May 9, 2016, more than four months into 2016; however, for ease of comparison and understanding, we have used calendar years for reporting certain data. Reporting hostile bid data based on 12-month periods ending May 9 would not have resulted in a material change in the data, given that only one hostile bid was commenced between January 1, 2012, and May 9, 2012, and no hostile bids were launched between January 1, 2016, and May 9, 2016. In addition, as at May 9, 2020, no hostile bids have been commenced in 2020. Furthermore, the new bid rules were debated for years and published in final form in February 2016, giving market participants notice that the effective date of the rules was imminent, which also may have affected behaviour during the first four months of 2016. In addition, given the dramatic and unprecedented sudden impact of COVID-19 on the global economy and M&A activity, we have not included any 2020 data in our analysis. We will continue tracking public M&A activity levels, and expect to report our findings in future publications.(go back)

Print

Print