Carine Smith Ihenacho is the Chief Corporate Governance Officer, Jonas Jølle is Head of Governance, and Vegard Torsnes is a Lead Governance Analyst at Norges Bank Investment Management. This post is based on their NBIM memorandum. A related video is available here: NBIM Talk: Investing responsibly.

Shareholder meetings are the main opportunity for shareholders to influence companies and hold the board to account. We use our voting rights to promote the fund’s long-term interests.

We own a small slice of more than 9,000 companies. As a minority shareholder, we are one of many contributors of equity capital to a company. We rely on the board to set the company’s strategy, oversee management performance and be accountable for its decisions. For stock companies to function effectively, most decision-making power is delegated to the board. Shareholders have the right to choose who will sit on the board and act in their best interests. Shareholders also have the right to approve fundamental changes to the company, such as amendments to governing documents, issuance of shares, and mergers and acquisitions.

The fund has come a long way since it initially avoided using its voting rights for fear of getting involved in difficult decisions. Today, the fund actively uses its voting rights at nearly all shareholder meetings. The fund has a principled approach to corporate governance that is applied consistently across the portfolio. The fund publishes all its votes the day after the meeting. In cases when we vote against the board’s recommendation, we provide an explanation. From 2021, we will publish our votes before the shareholder meeting and explain any votes against the board’s recommendation. We want to be fully transparent about how we exercise our ownership.

A reluctant owner

Exercising ownership rights, including voting at shareholder meetings, was not the intention when the fund began investing in listed companies. On the contrary, exercising ownership rights was seen as problematic, considering the resources required, our limited influence, and our status as a sovereign fund.

In the revised national budget for 1997, the government emphasised that the fund should be “a financial investor and not a tool for strategic ownership”. This was important for reasons of risk diversification, liquidity and availability of capital, as well as performance measurement so that the fund’s performance could be compared with that of other financial investors. Strategic ownership would also have required different expertise and close monitoring of the higher risks involved in actively influencing corporate decisions. The government stressed that “the fund’s ownership interests in individual companies shall be small” and set an ownership limit of 1 percent of the share capital of any one company.

Norges Bank also noted that this “spreads the risk and results in smaller variations, and also helps to avoid equity stakes of a magnitude which forces the investor into an active role as an owner.” Norges Bank estimated holdings of around 0.3-0.4 percent in European markets, given the proposed 40 percent allocation to equity, 50 percent allocation to Europe and a future fund size of 500 billion kroner.

When the fund first invested in equities in 1998, the exercise of ownership rights was subject to the following rule in the Regulation on the Management of the Government Petroleum Fund: “Norges Bank shall not exercise ownership rights linked to shares unless this is necessary in order to safeguard the financial interests of the fund.”

Norges Bank argued that if it were to make use of its voting rights, the Ministry would have to set “well-defined operational procedures, consistent with the ethical guidelines”. Using the fund’s voting rights would add operational costs and would probably lead to a reduction in revenue from lending securities.

By the end of 1998, the fund already held shares in 2,109 companies. An increase in the cap on ownership stakes became inevitable to allow for greater flexibility in the management of the fund. The cap was duly raised to 3 percent in 2000 to allow several external managers to invest in the same company without running the risk of exceeding the ownership ceiling. As the fund grew further, the cap was subsequently raised to 5 percent in 2006 and 10 percent in 2008. In 2016, an exception was made to the 10 percent cap for investments in listed real estate companies in order to facilitate the implementation of the real estate investment strategy in a market with limited investment opportunities.

Two different considerations gradually persuaded the fund to make more active use of its voting rights: promoting ethical behaviour in companies and protecting the investments of the fund.

Ethical behaviour

The fund first considered using its voting rights as an alternative to negative and positive screening. In 1997, the government had announced that it wanted guidelines for the fund with more emphasis on environmental and human rights issues. The Ministry of Finance raised the possibility of either excluding companies that did not meet certain criteria or including only companies that did. This led Norges Bank to consider different options for integrating such issues into the management of the fund.

Norges Bank cautioned that both approaches would reduce diversification and increase risk while complicating the management and monitoring of the fund. Norges Bank presented voting as an alternative. Voting could be used to “convince enterprises to attach importance to specific ethical issues […] without placing restrictions on the fund’s investment universe”. Norges Bank pointed to large US pension funds which had chosen to exercise ownership rights actively instead of excluding companies from their investment universe. Responding to a later proposal to include environmental criteria in the investment strategy, Norges Bank similarly argued that it could “safeguard environmental considerations by using voting rights”.

Norges Bank envisioned three potential ways of exercising ownership rights to influence the “ethical profile of companies”. This included dialogue with company management, tabling proposals at shareholder meetings, and voting only on motions of an ethical nature submitted by other shareholders.

Norges Bank argued that if ownership rights were to be exercised, the fund’s owner would first have to establish a set of specific ethical guidelines that would mention explicitly all the activities of concern to the fund’s owner, and a mechanism to translate these guidelines into the active exercise of ownership rights.

Norges Bank concluded that “whereas the use of voting rights would have a limited impact on the management of the fund, the exclusion of many companies from the fund’s investment universe might result in substantial costs and make it more complicated to engage in effective management with adequate control and performance measurement”.

Norges Bank made it clear that it considered exercising voting rights the least bad option, and that given the choice it would rather just get on with investing in an unrestricted universe. At the same time, Norges Bank declined to take responsibility for voting: “It is natural for the owner of the fund (the Ministry of Finance) to be responsible for voting.”

As we have seen, the government set aside the objections of Norges Bank, establishing in 2001 both a small environmental fund and an exclusion mechanism. Using voting rights as an alternative to negative and positive screening was not seriously considered. However, the debate on whether to exclude companies that violate ethical norms or own them to influence their behaviour continues to this day. Norges Bank later developed an effective interplay between exclusion and active ownership. Voting has, however, played little part in this interplay, as neither product selection nor business conduct are subject to shareholder approval. The fund has instead chosen meetings and written communication to collect information and present its views on companies’ behaviour.

Protecting investments

Corporate failures such as Enron in 2001, and Tyco and WorldCom in 2002, raised the question of how the fund could protect its investments. These failures revealed instances of mismanagement, or even fraudulent management, and a lack of board oversight. They also demonstrated that there was a need for shareholders to take a more active role in holding the board to account in order to safeguard investors’ long-term financial interests.

In parallel with awareness of the need for greater shareholder involvement by shareholders, regulators, stock exchanges and other market participants had strengthened the regulation and oversight of corporate systems and procedures for management, control and accounting.

Another important aspect was that large institutional investors had becoming significant owners. Through their diversified holdings, they held minority stakes in thousands of companies across the globe but were not able to monitor each of them effectively. This led institutional investors to re-evaluate the board as an alternative accountability structure to discipline management and deter wrongdoing. Most large pension funds published guidelines for the exercise of ownership rights based on shared interests, which were very similar to the principles of good corporate governance adopted by the OECD in 1999.

Along with these developments, substantial inflows of capital had increased the fund’s average holdings in global equity markets, particularly in Europe. While our ownership stakes had at first been so small that our votes would have had limited impact, our growing holdings pointed to a future where using our votes could soon have a greater impact on individual companies and broader market practices. Hence, voting could become relevant to the fund’s financial interests.

In the five-year period from 1998, when the fund made its first equity investments, to 2003, average equity holdings increased from 0.04 percent to 0.27 percent globally. In Europe, the fund owned almost 0.5 percent of every listed company by the end of 2003. The increase in percentage holdings and the possibility of exerting influence through co-operation with other institutional investors made it more likely that the fund could help protect its financial interests by exercising its ownership rights.

The fund already had some experience of exercising its ownership rights in individual companies, even if it did not participate in voting. Companies would regularly ask the fund, as a shareholder, whether to participate in tender offers and whether to receive cash or stock dividends. If the fund did not respond, the company would apply the default option which might not suit the fund’s investment strategy, liquidity needs or tax position. Just like voting, these corporate actions involve choosing between different alternatives that affect the company and, in some cases, other shareholders. Corporate actions, however, were limited in scope and decisions could be made through existing arrangements.

A principled owner

With the increasing use of voting rights and the need to co-ordinate voting decisions between different portfolio managers, the fund established an evolving set of guidelines for voting. These guidelines had to explain the objective of voting and specify how to vote on a wide variety of issues. As the fund began to vote at thousands of shareholder meetings, public guidelines became even more important to ensure consistency across the portfolio and to allow companies to understand why we vote the way we do.

Establishing principles

At the start of 2000, the fund began to run internal portfolios. The large external index mandates were terminated and brought in-house early in 2001. Internal and external managers had to make a broad range of decisions regarding the fund’s ownership rights in individual investments. Making the best decisions for the fund required co-ordination and clear guidelines.

On 14 February 2002, the fund established its first “Guidelines for Exercise of Financial Ownership in Foreign Stock Companies”. With these guidelines, the fund took an important step towards making more active use of its ownership rights. The fund was to protect the interests of the portfolio by taking a position on important questions that could affect shareholders’ long-term financial value. The guidelines listed the preferences of the fund: a clearly defined strategy and financial purpose of the company; exact, complete and timely information; one vote for each share; board accountability and regular board elections; and appropriate incentives for management. While the list seems uncontroversial today, at the time it signalled that corporate governance was relevant for protecting the interests of the fund. This was a clear break with the reluctant approach to ownership in the first five years of equity investment.

When the Ministry of Finance issued the new Regulation on the Management of the Government Petroleum Fund in December 2004, it also stipulated that the fund should exercise all ownership rights with the overall goal of safeguarding the fund’s financial interests. The regulation was supplemented by “Principles of Corporate Governance and Protection of Financial Assets” issued by Norges Bank in December 2004. The principles took as their starting point that corporate governance was important to protect the financial interests of assets under management: “Exercising ownership rights with a view to protecting financial assets is an integral part of sound portfolio management. Norges Bank expects company boards to be responsible for ensuring that operations are conducted in a manner that is in the owners’ long-term interests.” The principles were made public to be more open about how we would exercise our ownership.

In 2008, Norges Bank issued its first public voting guidelines. We already had internal guidelines for voting, but with their publication, companies, investors and other market participants could better understand our priorities. By then, the fund had become a significant owner, with equity investments in 7,531 companies and a global average stake of 0.5 percent. The guidelines reiterated that the overriding objective of voting was to safeguard the long-term financial interests of the portfolio. Being open about the principles that determine our voting became a defining part of our role as an owner. With published principles, we could show how we voted consistently at thousands of companies. We could be also be more predictable so that companies could understand why we voted the way we did.

The guidelines argued that the company should have a clearly defined business strategy, endorsed by the board of directors, that the company should disclose adequate information about its financial position and other relevant factors, and that internal management and control systems should be tailored to the business. The guidelines also argued that the company’s board should take account of the interests of all shareholders, that it should have a sufficient number of members with relevant and adequate qualifications and a majority of independent members, that the board could be held to account for its decisions, and that the company should report openly on its policy and actions in relation to human rights and its impact on the environment and local communities.

One issue that set us apart from many other investors was our principled view on the separation of chairperson and CEO. We believed that a clear separation of roles and responsibilities was necessary for the board to exercise objective judgement on corporate affairs and to make decisions independently of management. In most cases, we would vote against the election of the chairperson if he or she was also the CEO. This principled view was not always appreciated by affected boards and made some company interactions more difficult. Over time, we have observed a trend towards separation of roles. In the US, combined roles decreased from 44 percent of companies in the Russell 3000 index in 2012 to 34 percent in 2019. We continue to publish our view on the separation of chairperson and CEO, to explain our view in company meetings and to vote against relevant chairpersons.

With the growing size of the fund, interest in our ownership and voting also increased. At the beginning of 2010, the fund published a combined document entitled “Corporate Governance Principles and Voting Principles”. The principles were based on broadly accepted norms, in particular the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance. Many of the principles are still relevant today and can be found in our current voting guidelines. In 2012, the fund published a detailed discussion note on corporate governance which reviewed the academic evidence and suggested specific investor expectations on board accountability and the equal treatment of shareholders.

Voting at shareholder meetings consists mainly of making decisions on proposals put forward by the company’s board. In some markets, including the US, shareholders can also table resolutions. In order to influence the agenda at the meeting, the fund decided in 2009 to file its own shareholder proposals. In line with our principled view, we chose the separation of the roles of CEO and chairperson as the objective of our proposals. We selected five US companies that had combined roles without adequate measures in place to mitigate conflicts of interest.

Since 2006, we had engaged with the US Securities and Exchange Commission to make it easier for shareholders to propose alternative board candidates in the US market. We proposed giving shareholders proxy access as a cheaper and less confrontational alternative to the more aggressive proxy fights. In 2012, we filed shareholder proposals seeking bylaw changes at six US companies in order to give shareholders this right. We filed similar proposals seeking proxy access at five US companies in 2013.

The proposals received 30-40 percent support and significant public attention, even if none of them were adopted. They also contributed to publicising more widely the fund’s principled views on corporate governance. Other shareholders later filed similar proposals to strengthen the role of the board and protect shareholder rights. In 2019, 89 percent of US companies in the Russell 3000 index had proxy access.

In 2015, we conducted a major review of our voting principles. The fund was by then invested in over 9,100 companies and had an average stake of 1.3 percent in every listed company in the world. Companies, other investors and NGOs were paying increasing attention to our voting and calling on the fund to explain the rationale for individual votes. At the same time, we had observed that our votes against the board’s recommendation had increased to 15 percent, which made us appear less supportive of the board than many of our peers. In our voting, we had followed established and widely shared corporate governance principles on a broad range of issues while adding our own principles, including on the separation of chairperson and CEO. In combination, this led to a high number of votes against the board’s recommendation.

We carefully analysed the most important agenda items at shareholder meetings and how we had voted. We also compared our votes to those of other investors and to the advice provided by proxy firms. We found that our votes were broadly aligned with the market and that most of them stood up to scrutiny. However, we also found that we voted against the board’s recommendation on a range of large and small issues without a clear sense of prioritisation. This threatened to undermine our principled approach to voting and, moreover, reduce our impact at individual companies.

As a result, we decided to scale back and concentrate on a few core principles that would explain the majority of our votes. Our starting point would be to support the boards that we as shareholders had elected, unless we had a principled reason to withhold our support. When we published new voting guidelines in February 2016, we stressed four principles. First, the board must be accountable to shareholders. Second, the protection of shareholder rights is an essential requirement for minority shareholders. Third, the board is accountable for all information provided by the company. Fourth, the board should understand material risks and opportunities and integrate such matters into the company’s business strategy, risk management and reporting.

Our votes against the board’s recommendation dropped to 7.6 percent in 2015 and 5.5 in 2016. The main drivers for our against-votes were board accountability, in particular board members’ independence and the separation of chairperson and CEO, and shareholder protection, in particular share issuances that undermine our rights.

Following the review, we began to publish two-page position papers on our priorities in corporate governance. We wanted to clarify our principled views and be more open about the reasoning behind our voting. The first two position papers called for strengthened procedures for board elections with the purpose of improving accountability towards shareholders. We argued that shareholders should be able to hold board members to account by voting on each one individually. Boards should also publish the vote tally so the market could assess the level of support for board and management. Sweden was among the few advanced markets where boards were elected on a slate and where companies did not publish detailed voting results.

Taking a principled view on management incentives in 2017, we sought to strengthen alignment of CEO and shareholder interests through simplification of remuneration plans, emphasising transparency and long-term shareholding. In 2018, we argued our position on the time commitment and industry expertise of board members and on the separation of chairperson and CEO. In 2020, we further clarified our views on board independence, share issuances, multiple voting rights, related-party transactions, corporate sustainability reporting and shareholder proposals on sustainability issues. These positions serve as a starting point for our discussions with company boards and explain our voting.

In February 2020, the fund published more detailed voting guidelines, structured along six main principles for effective boards and shareholder protection. The guidelines consistently take as their starting point that we support the board, but that we will withhold our support if we consider that the board is not able to operate effectively or that our rights as a shareholder are not protected.

With more detailed guidelines, we are able to publish a principled explanation in those instances where we vote against the board’s recommendation. An effective board is the keystone of a well-governed company. The board should exercise independent judgement, without conflicts of interest. The board should fulfil its duties effectively and have an appropriate balance of competences and backgrounds. Board members should be accountable to shareholders for the outcomes of their decisions. The protection of shareholder rights is an essential requirement for minority shareholders in a listed company. Shareholders should have the right to obtain full, accurate and timely information on the company and to approve fundamental changes to the company. This includes the right to approve changes in capital structure affecting shareholders’ cash flow or voting rights. We expect all shareholders to be treated equitably.

Making voting decisions

Explicit voting guidelines enable co-ordination internally, and publishing them creates predictability about our ownership in individual companies. At the same time the guidelines need to be applied to a broad range of agenda items across markets in different jurisdictions. Each market and, to a large extent, each company is different. Global voting therefore requires gathering information about companies and markets, analysing them, applying careful judgement, and handling difficult issues. Since establishing its first corporate governance unit in 2005, the fund has balanced centralised co-ordination, based on principles, with integrating fundamental company insight from portfolio managers. With better company data and increasing use of analytical tools, we have been able to automate a majority of voting decisions and to concentrate our efforts on the most important.

As the fund grew in size, being consistent when voting at shareholder meetings became ever more important. Consistency means that our voting decisions can be explained on the basis of our principles. When we apply our principles, we evaluate company developments and take into account best practices in the local market. The nature of some proposals requires that we consider them individually. In such cases, we have to use judgement when applying our principles. Consistency does not mean that we will vote in the same way each year, or at all companies and on similar issues.

We have used an online platform since 2003 that brings together all necessary information about upcoming shareholder meetings. The platform includes all of the resolutions to be voted on, the board’s position on these resolutions, standardised voting recommendations by competing advisors, as well as the relevant deadlines and technical details. Applying the fund’s own global voting guidelines, we receive initial voting recommendations on all resolutions. While we have continuously refined our voting guidelines and strengthened our analytical capabilities, the process remains largely unchanged. Selected companies are analysed internally and escalated for further consideration when necessary. Company-specific factors and fundamental insight are integrated on a case-by-case basis. If no changes are made, the vote is cast automatically, based on our voting guidelines.

The involvement of portfolio managers in voting decisions was formalised in 2013. Each portfolio manager with an active management mandate was asked to analyse the shareholder meeting agenda and provide recommendations on the resolutions subject to a shareholder vote for important companies in his or her portfolio. Fundamental insight from portfolio managers helped us apply our principles more accurately at the individual company. The involvement of portfolio managers in the voting process has also given the portfolio manager a deeper understanding of the companies’ governance.

The involvement of portfolio managers in the voting process has strengthened in recent years. In 2013, portfolio managers were involved in 7.3 percent of voting decisions. In 2019, portfolio managers were involved in 9.4 percent of voting decisions. Since portfolio managers concentrate on many of the largest companies in the portfolio, their voting input relates to about 50 percent of the value of the equity portfolio.

While the majority of our voting decisions fall within the scope of our public voting guidelines, there are cases where our guidelines do not give a clear answer. Some resolutions are contentious by nature or fall outside the established voting framework. In 2015, we established a referral system to cope with such cases. We analyse the proposals individually and vote on the basis of what is considered to be in the best long-term interests of the company and the fund. Common examples of such cases have been extraordinary general meetings to vote on mergers, acquisitions or capital issuances, and other important events affecting the company.

Resolutions tabled by shareholders on sustainability issues are particularly likely to require individual analysis. These resolutions cover a broad range of social and environmental issues in a format that is not standardised. They make up only 0.2 percent of all the resolutions we vote on, but are often the most difficult decisions we make. We have seen an increase in the number of shareholder resolutions addressing environmental and social issues. Some of these resolutions have helped improve risk management, while others have diverted attention away from core business. The proponents of these resolutions may be long-term investors such as us, or activists with special interests. Our support for these proposals has varied between 27 and 52 percent in the last seven years, depending on the nature of the proposals and the company in question. With such variation, we were not able to be as consistent and predictable in our voting as we wanted.

In 2019, we formalised a set of three criteria for evaluating shareholder proposals on sustainability. First, the issue at hand should be materially relevant to the company. Second, the proposal should not seek to impose a strategy, or prescribe detailed methods or unrealistic targets for implementation. Third, the proposal should be considered in light of what the company is already doing. With these criteria, we aim to make consistent voting decisions on a mixed bag of issues, with reasonable use of our resources.

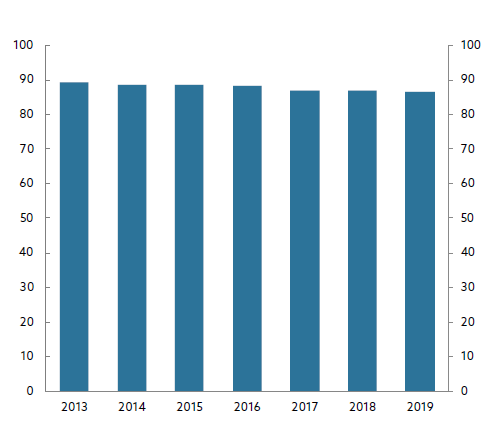

With shareholder proposals as a clear exception, the vast majority of the roughly 115,000 resolutions we vote on each year fall within the scope of our published voting guidelines. Extensive data on companies and detailed guidelines put us in a position to automate most voting decisions. This is necessary in order to handle a vast number of resolutions in a short period with reasonable resources. Automation also means that we can ensure a high degree of consistency and that we can measure trends in corporate governance and market practices over time.

Roughly 87 percent of voting decisions have been automated. These decisions are mainly associated with smaller companies representing approximately 30 percent of the value of the fund’s equity portfolio.

The voting guidelines we published in 2020 are more detailed and specific, using binary rules and quantitative thresholds where possible. With more and better company data on corporate governance, we are able to automate the voting process further. This will help us calibrate our voting decisions more accurately, based on our own principles, and improve overall quality and consistency. Automation will also help focus our limited human resources on the companies and voting decisions that matter most for the financial value of the fund.

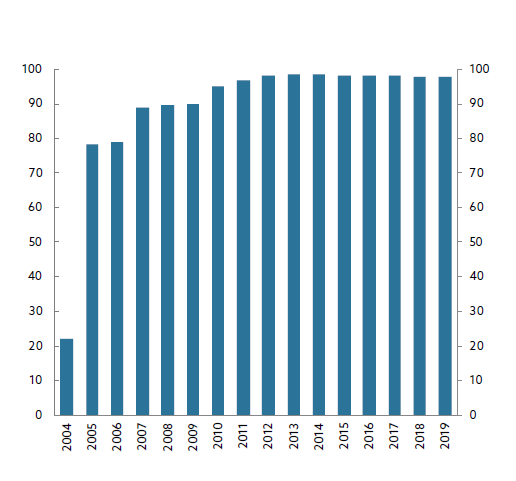

Voting. Share of shareholder meetings voted by year. Percent.

Voting. Share of automated votes by year. Percent.

A transparent owner

Since we started voting in 2003, we have become increasingly open about how we vote. As a large shareholder, we face growing interest in our voting from companies, investors and other market participants. The Norwegian population, as beneficiaries of the fund, wants to know how we use our ownership rights. Being open about how vote makes us predictable as an owner and makes us accountable for our decisions. Our next goal is to publish all our voting decisions, with an explanation, ahead of each shareholder meeting.

Voting decisions

In the early years, from 1998 to 2000, the fund had little insight into the voting decisions that external managers made on behalf of the fund. In 2001, we started to receive monthly reports from our custodian bank showing how external managers had voted. The first voting records show that external managers voted at 31 percent of the shareholder meetings where we had voting rights. External managers exercised our rights only when they had identified a financial interest.

The fund began reporting annually on its voting decisions in 2003, after it had cast the first vote at a company in an internally managed portfolio. In that year, shareholder meetings were held at about 2,000 companies in internally managed portfolios. At this point, the fund chose to concentrate its voting rights on the 150 largest companies in the portfolio, which made up more than 50 percent of the equity portfolio’s value.

The fund’s annual report contained information on the number of shareholder meetings at which we had voted, the total number of votes cast and the share of votes against the recommendations made by company boards. In the period between 2003 and 2007, voting increased six-fold, from 650 shareholder meetings to 4,202. Although the number of companies in the portfolio grew significantly in this period, the increase was mainly driven by an expansion of voting to a broader range of issues. By 2007, the fund voted against board recommendations in 9.5 percent of cases, mainly driven by opposition to the election of board members.

Starting in 2008, the fund began to publish all its voting decisions at individual companies the previous year when launching our annual report. The data were made available on our website. We supplemented our voting disclosures with explanatory comments and descriptions of our voting priorities.

In the period between 2007 and 2013, voting doubled again, from 4,202 to 9,683 shareholder meetings. The number of companies in the portfolio grew by 10 percent in the period. Improvements in the voting process and the removal of share blocking in many markets allowed us to further expand our voting. By 2013, the fund voted against the board’s recommendation in 13.8 percent of cases, which was more than most of our peers.

In 2013, there was a public debate on holding the board of JPMorgan Chase & Co accountable for failtures in its risk oversight process following significant trading losses. Our voting decisions had become an important reference point for other investors and our own stakeholders. This was particularly so in high-profile cases following the global financial crisis. Communicating our voting decisions in an annual report, several months after the shareholder meeting, was seen to be too slow. The fund committed to becoming even more transparent.

In the third quarter of 2013, we began publishing our voting on the fund’s website one business day after each shareholder meeting. This increased our transparency on voting and how we exercise our rights.

In the period between 2013 and 2019, voting increased by another 20 percent, from 9,583 to 11,518 shareholder meetings. The number of companies in the portfolio grew by another 10 percent in the period. Further improvements in the voting process allowed us to expand our voting yet again. In the same period, we reviewed our voting guidelines, which resulted in our votes against board recommendations stabilising at 5 to 6 percent of all votes. This demonstrated our starting point of supporting the board unless we had principled reasons to withhold our support.

Voting rationales

We have published our voting decisions since 2003 and our voting guidelines in different versions from 2006. This has allowed companies, investors and market participants to understand how we voted and what principles guided our decision. We have generally not commented on specific votes or provided a public rationale since we did want to single out individual companies or board members.

In April 2020, the fund pushed transparency on voting to a new level. We began publishing a rationale every time we voted against the board’s recommendation. The published rationale is part of our continuous disclosure of all voting decisions, one business day after the shareholder meeting. The rationale is derived from the recently updated voting guidelines and provides a principled explanation for all votes against the recommendation of the board.

Voting intentions

In some instances, we have published our voting intention ahead of the meeting. We have done this to draw attention to important principles at select companies. In these cases, we have informed the relevant company in advance of publishing our voting intention. We have mainly chosen to express our support of resolutions that align with our principled view. We published our first voting intention in 2015 to support the special shareholder resolutions on climate reporting at BP and Royal Dutch Shell. Both resolutions were approved by a significant majority.

In total, we have published 21 voting intentions, mainly on climate risk, mergers and board elections. The majority of proposals were tabled by shareholders. While we believe that publishing our voting intentions at individual companies is an effective way of communicating our principles, we also acknowledge that the approach is selective and skewed towards markets with many shareholder proposals.

To further enhance transparency on voting, we will publish all our votes in advance of the meeting from 2021. Our intention is to provide more information to the market and to be fully transparent about how we use our voting rights. We are concerned that a lack of information makes the market for voting advice not fully efficient.

The complete publication is available here.

Print

Print