Philip Zanfagna is a Business Analyst, Molly Farber is former Managing Director, and James Bamford is a Senior Managing Director at Water Street Partners. This post is based on their Water Street Partners memorandum.

When companies decide to pursue a joint venture (JV), a critical first step is determining the appropriate level of ownership and control. Given a choice, most companies would prefer to be the majority partner, believing such a structure provides greater control and decision-making efficiency. Being a minority partner, however, is also appealing in certain cases by limiting capital outlays, reducing operating responsibility and resource demands, lowering risk exposures, and keeping the JV off of the company’s consolidated financials. [1] A third option is a 50:50 joint venture.

There are a number of factors that might drive JV partners to an equal equity split. Most simply, such structures reflect the partners making equivalent cash and non-cash contributions to the venture upon formation. Beyond this, equal ownership might be a function of regulatory requirements for local partners to hold at least a 50% ownership stake, or a reflection of neither party wanting to consolidate the venture’s financials. The choice of 50:50 is often the default practical solution for partners when contributions are roughly equal and neither is willing to cede control. Or, companies may favor 50:50 ownership due to a desire to build an independent, long-term sustainable business based on balanced contributions, risks, and rewards between complementary partners.

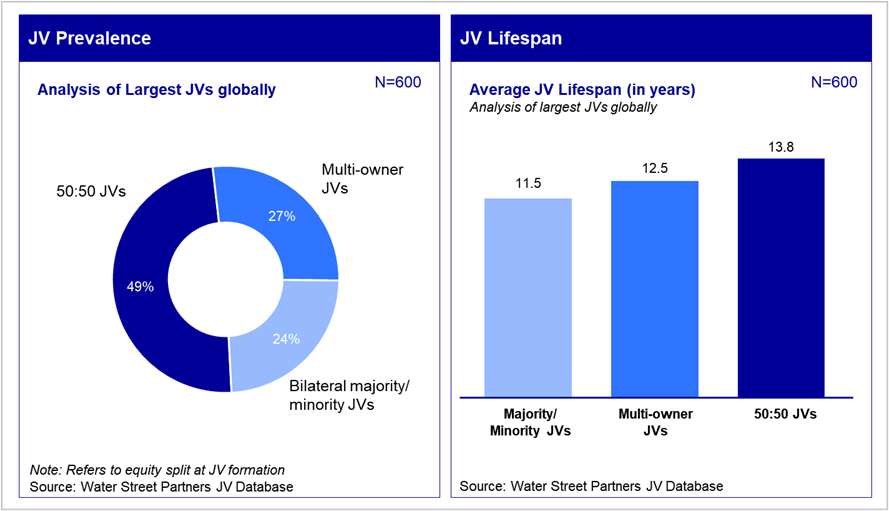

Our recent benchmarking of key demographic details of the world’s 600 largest joint ventures formed since 1990 shows that 50:50 ventures are the most prevalent ownership structure across industries, compared to asymmetric bilateral and multi-owner JVs, and also have a longer average lifespan (Exhibit 1). In certain circumstances, research shows they can even outperform other structures. [2] Notable ventures with 50:50 ownership include Chevron Phillips Chemical, a global chemicals JV founded in 2000 between Chevron and Phillips; Hulu, a media streaming venture founded in 2007 between NBC Universal and News Corp (and now a 67:33 JV between Disney and Comcast); and Dow Corning, the silicon joint venture founded in 1943 and acquired by Dow in 2014.

Exhibit 1: 50:50 JV Prevalence and Lifespan Data

Notwithstanding the above, many companies are justifiably hesitant to enter into 50:50 joint ventures. The principal fear is decision gridlock, with the owners failing to reconcile competing strategies and investment appetites and trapped in JVs with no path forward. Other fears include a lack of clear accountability for either partner to make the venture a success, or to establish adequate controls and manage risk. Companies are also rightfully concerned about JV management emerging as a de facto third partner, playing the owners against each other while promoting its own growth agenda.

Benchmarking of joint venture legal agreements validates some of these concerns. Our review of voting and related terms in 30 JV agreements with 50:50 ownership shows that most equally-owned JVs lack basic contractual protections against decision deadlock and related risks. While creative mechanisms for more efficient JV decision-making do exist, they are not present in the majority of 50:50 JV agreements.

The balance of this post describes key findings from our analysis and provides five creative structuring solutions to avoid decision-making impasses in 50:50 ventures.

Key Findings From Our Benchmarking

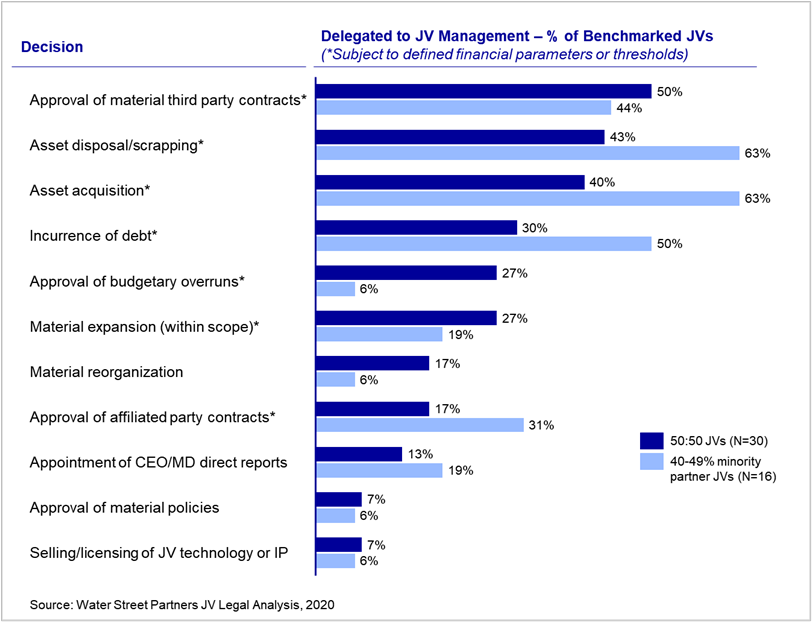

Voting Thresholds. It should come as no surprise that the majority of material decisions in 50:50 JVs require both partners’ approval. In our benchmarking, we looked at 38 decisions commonly defined in joint venture legal agreements. These decisions included both foundational decisions (e.g., amendments to the JV legal agreements, admission of new JV owners, and dissolution) that are often reserved owner decisions, and business decisions (e.g., major plans and budgets, M&A and material investments, and affiliated party contracts) that are often decided by the JV board. In almost all 50:50 JVs, a broad range of foundational and business decisions require both owners to agree. This approval is usually stated explicitly, though may also be implicitly required. Relative to the latter, due to different drafting approaches, certain decisions may be not specified in the legal agreements but are encompassed by other decisions that are explicitly defined. For example, 87% of agreements we reviewed explicitly require both parties to approve admission of a new partner. Because such admission would require an amendment to the JV Agreement, which requires the approval of both parties in 100% of the agreement reviewed, such approval is effectively required in the 13% of agreements that do not explicitly list this as a decision. We also compared the decision rights of 50% JV partners against the rights afforded to minority partners in a set of JV agreements featuring ownership levels of 40-49% (Exhibit 2), and found that the step up from 49% to 50% equity typically comes with a major increase in voting powers. 50% owners are more likely to have approval rights over decisions like approving plans and budgets, modifying material JV policies, and admitting or substituting new JV partners. [3]

Exhibit 2: Partner Approval—Equal vs. Large Minority Partners

Practically speaking, JV dealmakers evaluating 50% vs. 49% stakes must weigh these incremental voting rights with the increased risk for deadlock and potential diminishment of efficiency. Accepting a minority position may need to be paired with a broader slate of non-voting controls, influencing levers—such as seconding key venture employees, participating in technical or advisory committees, or providing important services to the JV—and other minority partner protections. Conversely, if committed to the 50:50 construct, companies should ensure that the joint venture agreement has appropriate deadlock mechanisms in place—which, as we discuss below, should involve tailoring terms for the decisions where JV shareholders’ views are most likely to diverge.

Dispute Resolution and Deadlock. Given the inherent risk of deadlock in 50:50 JVs, we expected to find robust mechanisms in the joint venture agreements to handle shareholder stalemates. Instead, we found most agreements only contained boilerplate dispute resolution terms, implying that many 50:50 ventures are under-prepared for inevitable shareholder misalignment. Of the 30 agreements we analyzed, 80% contained basic provisions for internal escalation to resolve disputes (i.e., passing the disagreement up the chain of command for additional negotiation). For disputes that persist beyond the escalation process, however, many agreements lack sufficient guidance. 57% of the 50:50 JV agreements we reviewed directed the parties to binding arbitration to address sustained disputes. A smaller proportion of agreements (17%) also established a path to non-binding mediation (Exhibit 3). More dynamic problem-solving mechanisms that created tailored outcomes for specific deadlocks—including allowing the prior year’s budget to carry over into the next year in the event of non-agreement, the use of sole risk provisions that allow one partner to make certain investments without other partner, and an adjustment to the voting structure triggered by certain events—were observed in some agreements (43%), but were less prevalent than we would have hoped to see.

Even the option to exit or terminate the venture in case of sustained deadlock was only specified in 27% of 50:50 agreements we reviewed. This included options for a partner buy-out or dissolution of the venture. By comparison, analysis of other legal agreements in our database shows 28% of asymmetrical bilateral JVs permit exit in case of deadlock, as do 9% of multi-partner JVs.

The lack of flexible escape hatches in many 50:50 JV agreements should be a cause for concern. While prevalent and appropriate in certain cases, standard-form dispute resolution mechanisms risk being too cumbersome to address typical disputes—e.g., relating to budgeting, capital planning, appointing and managing top leadership—that are more likely to arise between JV partners in the regular course of the venture’s business. Only one of the JV agreements in our sample specified an expedited “baseball” style of arbitration, requiring the arbitrator to choose between the two partners’ submitted positions without modification—a structure that in our experience is increasingly used in commercial agreements to incentivize the parties to put forward reasonable positions from the start and resolve disputes in a timely manner. Alternatively, more tailored or dynamic terms—which show up in less than half of the agreement we analyzed—can position the JV and its shareholders for more efficient decision-making and reduced risk of governance gridlock.

Exhibit 3: Benchmarking Deadlock Mechanisms in 50:50 JVs

Creative Solutions

So, the question becomes, how should partners properly address this threat of deadlock?

We have advised on hundreds of joint venture transactions, and based on that experience, six creative contractual mechanisms for mitigating deadlock in 50:50 JVs stand out as the most effective. Their implementation is not universal, and needs to be based on the nuances of each venture and tailored by dealmakers to specific situations where misalignment and deadlock may occur.

1. “Golden Share.” For certain decisions, it may be appropriate for one JV shareholder to have a casting vote. This may be a threshold matter during negotiations—for example, in the case of a biofuels JV, where one partner contributing substantial local assets to the venture would only agree to the deal so long as it maintained incremental voting rights on key planning and funding decisions for those contributed assets. It may also be justifiable if one shareholder has special technical expertise, or if JV assets are deeply integrated with shareholder assets (and therefore present unique risks to that shareholder).

Another permutation on the “golden share” model is a more democratic model used by a Middle Eastern chemical joint venture. This venture affords a casting vote on certain mid-level financial decisions to the Chair of the JV Board. These types of decision include operating expense budget revision between 5-10% of the approved budget and approving capital projects worth between $1-$3 million. The Chairman appointment rights, however, rotate annually between shareholders, meaning that the parties trade-off when their appointee has these casting vote privileges.

Exhibit 4: Prevalence of Sole Risk Provisions in 50:50 JVs

2. Sole Risk Provisions. For major project and investment decisions prone to deadlock, sole risk or “opt-in/opt-out” provisions may also be appropriate. For decisions that fail to meet the specified Board or shareholder approval threshold, sole risk terms permit the interested shareholder to pursue the investment in question independently, while shielding the non-participating partner from any associated liabilities or These provisions are more prevalent in technology-commercialization JVs, upstream oil and gas JVs, and other ventures where future capital investments—including associated revenues, costs, and liabilities—can be cleanly separated from the main venture [4]. Our data, however, shows that only 12% of cross-industry 50:50 JVs include such provisions (Exhibit 4).

Well-designed sole risk provisions can be a dynamic solution to sidestep deadlock and maintain the productivity and growth of the JV. They not only offer a growth-oriented shareholder greater investment flexibility, but also protect less flush partners from dilution in the core JV assets or business.

For dealmakers considering sole risk provisions in 50:50 or other JVs, certain threshold conditions do need to be present. The JV needs to be able to carve out specified investments from its legacy operations, and thereby ensure that the non-participating owner is not exposed to any associated liabilities. Additionally, comprehensive sole risk provisions should contemplate ancillary terms—e.g., whether the non-participating party is permitted to opt back into the project at a later date (and if so, at what terms), and terms at which the sole risk project can leverage core JV capabilities (e.g., via technology license, or contracting for support from the JV team at commercial rates).

3. Pre-Agreed or Default Plans in Case of Deadlock. Another way to de-risk JV decision-making is to pre-wire plans and actions in response to deadlock where possible. Budget carryover provisions are the most common example of this, appearing in 30% of the agreements we analyzed. These terms basically serve as a stop-gap protection. When the JV Board cannot agree to a new annual budget, the prior-year budget automatically applies (sometimes with a pre-calculated percentage increase, often linked to inflation) until a new budget can be agreed. This allows the JV to maintain operations uninterrupted, and reduces the risk of value destruction or operational incidents while the JV Board deliberates.

This approach to mitigating deadlock can also be applied more broadly. For instance, to mitigate the risk of partner disagreement during a new venture’s formative years, the partners might consider pre-agreeing to an initial 2- to 5-year business plan, which commits the parties to certain mandatory funding, technical, and service contributions. For JVs charged with developing technology or scaling new products, the partners can pre-agree to development or commercialization milestones that, if met, trigger future capital infusions. These pre-agreements can also extend to decisions like the dividends/distribution policy, an item that can create friction between the JV partners but may not be not worth halting JV progress and initiating dispute settlement mechanisms to negotiate.

4. Broader Delegations to JV Management. Delegating more decisions to JV management—subject to appropriate Board or shareholder controls, and potentially limited by monetary thresholds—is another underutilized tactic to increase governance efficiency and avoid stalemates at the Board or shareholder levels. We found that 50:50 JVs do not consistently use delegations to JV Management as an approach for dealing with deadlock and that 50:50 JVs are actually not any more likely to delegate decisions to JV Management than asymmetric bilateral JVs (Exhibit 5). [5]

Exhibit 5: Delegations to JV Management—50:50 vs. Other Bilateral JVs

Exhibit 6: Treatment of Non-Specified Decisions

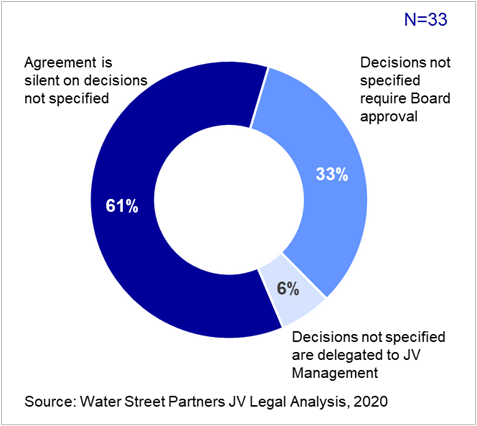

There are additional contractual mechanics that can afford JV management more responsibility. No contract is capable of pre-ordaining every decision the JV must take, meaning that there will always be a substantial category of decisions not otherwise specified that need to be addressed. An efficient solution is for the JV agreement to include a blanket clause that delegates decisions not otherwise specified to a certain group or decision process. Phrases like “all day-to-day operational decisions not otherwise specified in this agreement will be left to Joint Venture Management” are effective contractual inclusions that can increase the efficiency of the JV and help mitigate the risk of deadlock (though the clause does not have to be as sweeping to be helpful). We found, however, that 61% of the agreements we analyzed fell silent on the treatment of non-specified decisions (Exhibit 6). [6] This is a recipe for deadlock that, with only a few short sentences (or in some cases, just one sentence), can be avoided. The lack of JV Management delegations seems to indicate that 50:50 dealmakers are more focused on protecting their respective shareholder’s rights than mitigating deadlock. This is understandable in certain situations, like when the JV is a captive utility to the shareholders or the JV Management is seconded from a counterparty, but there is still value being left on the table by not taking a more critical eye to the potential role and authority of management.

5. Voting Rights De-Linked from JV Ownership or Economics. JV dealmakers should also consider de-linking ownership and economics from voting interests for more flexibility in negotiating new ventures. For instance, in Raizen, a multi-billion dollar downstream oil and biofuel joint venture between Royal Dutch Shell and Cosan formed in 2010, the partnership is structured into multiple 50:50 JVs with variable voting interests to promote accountability and decision making efficiency. In the downstream JV, which consolidated the Brazilian downstream refineries and retail fuel stations of the two companies, Shell is a 50% owner but has 51% voting interests. In the biofuels JV, which is the companies’ exclusive vehicle to produce, sell, and trade sugar-derived biofuels globally, Cosan has 51% voting interests, along with 50% ownership and economic interests. [7]

A variant of this model is found in an automotive manufacturing JV in China between a European company and a local Chinese partner. The European shareholder controlled the JV Sales Committee—to which the Board delegated decisions related to dealer selection and management—as a means to protect and control its brand and distribution strategy in the world’s most important market.

In some ventures, this concept is flipped on its head, with owners with asymmetric ownership seeking 50:50 decision rights. Prominent examples include MillerCoors, a U.S. beer consolidation JV between Molson Coors and SABMiller which had a 58:42 economic rights structure and 50:50 for voting; Aera Energy, a 52:48 JV with 50:50 voting between ExxonMobil and Shell that operates onshore assets in California; and Cingular, a now-terminated JV between BellSouth and SBC Communications. Typically, the parties are intent to establish a “partnership of equals” voting construct but need to solve for asymmetric contribution resulting in valuation gaps.

6. Appointing Independent Directors on the JV Board. Partners should also consider contractually including Independent Directors to serve on the JV Board. While only 20% of JV Boards leverage Independent Directors, they can serve as a neutral facilitator to JV Board deliberations (with or without a vote), bringing an independent perspective and potentially offering other special technical or market expertise. [8]

An approach like this was taken by a multibillion dollar 50:50 aerospace and defense JV. The scope of this deal was a point of contention for both parties, prompting negotiators to create an Independent Director position that had the sole authority to decide whether an opportunity was within or outside the JV’s scope. This Director had no other voting privileges, and their only job was to assess how germane outside solutions were to the JV’s contractually agreed upon scope.

Non-Contractual Solutions

Of course, contractual provisions are only half the battle. An experienced JV dealmaker we know often says, “If you’re turning to the legal agreements, things are already off the rails.” In that spirit, JV Boards and management teams should also consider the broad array of other governance practices to mitigate deadlock and improve JV governance health and productivity. These include:

- Aligning on JV Guiding Principles—a document or equivalent policy that supplements JV legal agreements and clarifies the shareholders’ expectations for growth, investment, use of JV resources, and other matters.

- Designating Lead Directors or Board sponsors of JV strategic initiatives—individuals tasked with helping to collaboratively shape proposals that require Board approval and serve as an advocate for the JV within their shareholder companies—thereby reducing the risk that key proposals meet a governance stalemate at the Board.

- Convening other technical or advisory committees—to collect shareholder input and proactively secure buy-in for JV initiatives or investments.

- Prior to deal close, investing in “misalignment scenario planning”—to inform the drafting of contractual terms—e.g., pre-agreed plans, funding milestones, investment tranches—or other policy documents and imbue them with language offering the flexibility to address reasonable future outcomes. [9]

These governance adjustments are not exhaustive or universally applicable to every JV, but the suggestions here are an effective starting point for dealmakers to keep partners aligned and mitigate the risk of deadlock.

*****

To be clear, 50:50 joint ventures hold significant promise. They often bring together highly complementary partners to build innovative new capabilities or business models. If well-designed, their governance models can enable highly collaborative decision-making, without the risk of mistrust or high oversight burden on the part of a non-controlling partner in an asymmetric bilateral JV. Delivering on this promise, though, may be predicated on more intentional design of their voting terms and processes. Negotiating better and more creative deadlock terms may not be simple, but it can change the outlook for your 50:50 venture.

Endnotes

1As a general rule, companies that are controlling majority shareholders of JVs consolidate them into their financial statements; companies that own 20-50% utilize equity accounting and report their share of the JV’s net income; and companies that own less than 20% carry the value of their shares as an investment asset. However, the actual ability to consolidate or utilize equity accounting is situation-specific; for example, a 55% owner with a strong minority partner may not have enough control to consolidate, and an 18% owner with outsized rights may be able to utilize equity accounting. However, this post should not be construed as providing any specific accounting or legal advice or recommendations.(go back)

2A 1991 analysis of 49 cross-border JVs indicated that 50:50 ventures were more likely to succeed relative to the partners’ objectives, as compared to asymmetrical bilateral JVs. See Joel Bleeke and David Ernst, “The Way to Win in Cross-Border Alliances,” Harvard Business Review, Nov-Dec 1991.(go back)

3For the benchmarked decision, there is no discrimination between decisions taken at the JV Board versus Shareholder levels, the data simply indicates that the decisions require both partners approval to pass.(go back)

4For more on this, see Edgar Elliott, Lois D’Costa, and James Bamford, “Agreeing to Disagree: Structuring Future Capital Investment Provisions in Joint Ventures,” Journal of World Energy Law and Business, May 2020.(go back)

5CEO delegations of authority are often internal company policy documents, which we do not always have access to see. Our benchmarking of these delegations, therefore, may be incomplete.(go back)

6For additional detail, please see: James Bamford and Joshua Kwicinski, “Voting Rights and Delegations: Unless Otherwise Agreed…,” The Joint Venture Exchange, October 2017.(go back)

7For additional discussion about creative joint venture ownership structures and operating models, please see: James Bamford, “Mixed Operator Models,” The Joint Venture Exchange, January 2014.(go back)

8This 20% represents Independent and Quasi-Independent Directors on JV Boards. For more on this, see James Bamford and Shishir Bhargava, “Independent Directors For Joint Venture Boards,” Corporate Board Magazine, January/February 2020.(go back)

9For additional discussion, please see James Bamford, Piers Fennell, and Joshua Kwicinski, “Misalignment Scenario Planning in Joint Venture Dealmaking,” The Joint Venture Deal Exchange, July 2014.(go back)

Print

Print