David H. Kistenbroker, Joni S. Jacobsen and Angela M. Liu are partners at Dechert LLP. This post is based on a Dechert memorandum by Mr. Kistenbroker, Ms. Jacobson, Ms. Liu, Christine Isaacs and Siobhan Namazi, and Austen Boer.

Notwithstanding a year of unprecedented economic and societal change amidst a global pandemic, non-U.S. issuers continued to be targets of securities class actions filed in the United States. Indeed, despite widespread court closures due to the coronavirus pandemic, 2020 continued to see an uptick in the number of securities class action lawsuits brought against non-U.S. issuers. It is therefore imperative that, regardless of the economic climate, non-U.S. issuers stay vigilant of filing trends and take proactive measures to mitigate their risks.

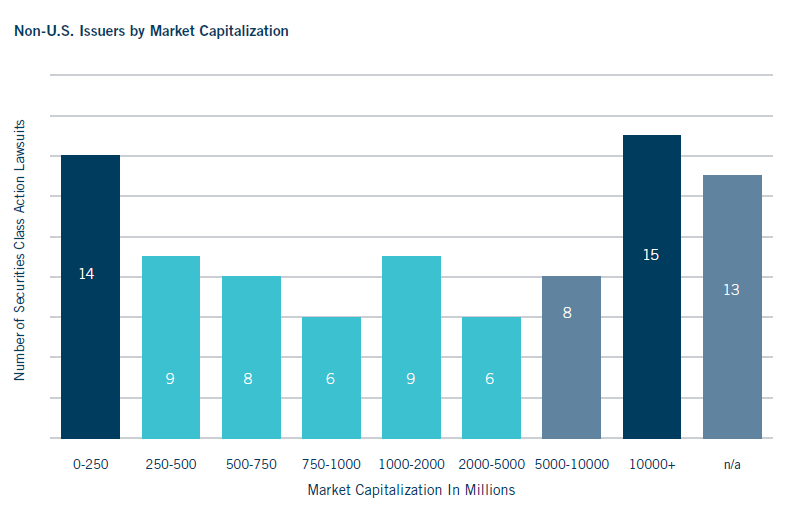

In 2020, plaintiffs filed a total of 88 securities class action lawsuits against non-U.S. issuers.

- As was the case in 2019, the Second Circuit continues to be the jurisdiction of choice for plaintiffs to bring securities claims against non-U.S. issuers. More than 50% of these 88 lawsuits (49)3 were filed in courts in the Second Circuit. A clear majority (35) of these 49 lawsuits were filed in the Southern District of New York. The next most popular circuit was the Third Circuit, with 22 lawsuits initiated in courts there. The Ninth and Tenth Circuits followed with 15 and two complaints, respectively.

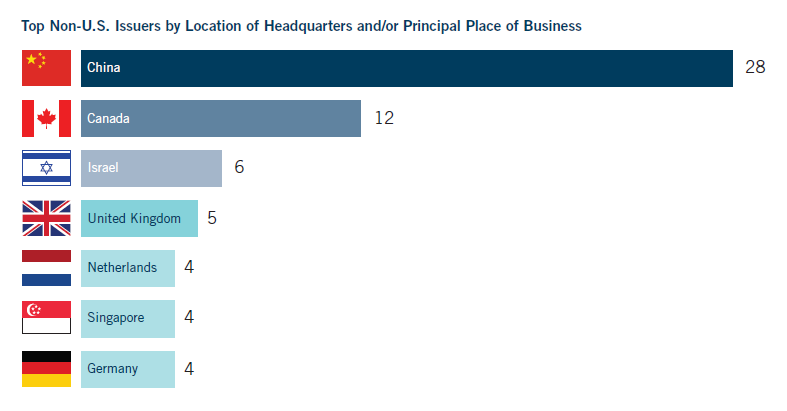

- Of the 88 non-U.S. issuer lawsuits filed in 2020, 28 were filed against non-U.S. issuers with a headquarters and/ or principal place of business in China, and 12 were filed against non-U.S. issuers with a headquarters and/or principal place of business in Canada.

- As was the case in 2018 and 2019, the Rosen Law Firm P.A. continued to be the most active plaintiff law firm in this space, leading with most first-in-court filings against non-U.S. issuers in 2020 (25). However, departing from the trend of the last several years, Pomerantz LLP was appointed lead counsel in the most cases in 2020 (14); the Rosen Law Firm closely followed with 13 appointments as lead counsel.

- Remarkably, the majority of the suits (28) were filed in the 2nd quarter, at the height of the coronavirus pandemic for most areas throughout the United States, particularly in the Southern District of New York.

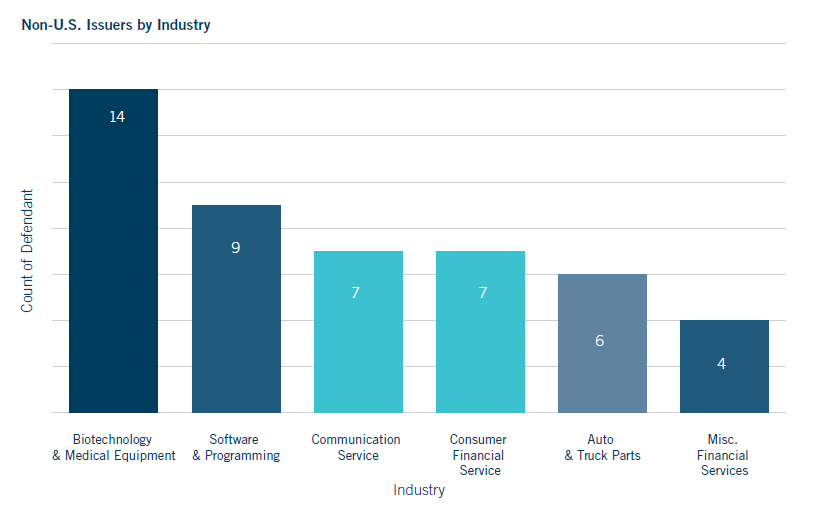

- While the suits cover a diverse range of industries, the majority of the suits involved the biotechnology and medical equipment industry (14), followed by the software and programming industry (9), the consumer and financial services industry (7), and the communications services industry (7).

- Of the 22 lawsuits brought against European-headquartered companies, five were filed against firms headquartered in the United Kingdom and four were filed against firms headquartered in Germany.

An examination of the types of cases filed in 2020 reveals the following substantive trends:

- About 19% of the cases involved alleged misrepresentations regarding mergers and acquisitions (17).

- About 9% of the cases involved alleged misrepresentations in connection with regulatory requirements and/or approvals (8). This includes one case involving alleged misrepresentations in connection with a non-U.S. issuer’s COVID-19 antigen test.

- About 8% of the cases involved alleged misrepresentations in connection with the solicitation and sale of blockchain assets pursuant to an Initial Coin Offering (“ICO”) (7).

Compared to 2019, 2020 saw relatively no change in the number of dispositive decisions4 issued in securities fraud cases against non-U.S. issuers. In 2020 (and early 2021), courts rendered nine dispositive decisions in cases filed in 2018 and 2019.5 In addition, 20 filings in 2020 were voluntarily dismissed in their entirety.

Although it is hard to discern trends from nine dispositive decisions, courts’ reasoning for dismissing cases is still instructive for non-U.S. issuers which find themselves the subject to a securities class action. In 2020 (and early 2021), courts dismissed complaints:

- relating to China-based, Cayman incorporated companies that went private and later relisted;

- for failing to allege a domestic transaction underlying a Section 10(b) claim;

- for failing to plead fraud relating to financial issues;

- for being time-barred, and

- for lacking personal jurisdiction.

Non-U.S. Companies Remain Popular Targets for Securities Fraud Litigation

In recent years, non-U.S. issuers have become targets of securities fraud lawsuits, a trend which continued in 2020 despite unprecedented economic and societal changes. Indeed, 2020 saw an uptick in securities class actions filed against non-U.S. issuers. This survey is intended to give an overview of securities lawsuits against non-U.S. issuers in 2020. First, we analyze the number of cases filed, including trends relating to location filed, types of companies that were targeted, and underlying claims. Next, we analyze some dispositive decisions rendered in 2020 and early 2021 and how they impact the legal landscape of these types of claims. Finally, we set forth issues and best practices non-U.S. issuers should consider to reduce the risk of being subject to such suits.

Filing Trends

2020 predictably saw a decrease in the total number of federal securities class actions, with 324 cases filed.

However, the number of cases filed against non-U.S. issuers increased significantly from the previous year, with just over 27% of lawsuits (88) filed against non-U.S. issuers, compared to 2019 in which 15% of the class actions were filed against non-U.S. issuers. As in years past, certain filing trends emerged:

- The Second Circuit, and particularly the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”), continued to see the most activity in 2020; with 31 filings, SDNY was the preferred court for 35% of all lawsuits brought against non-U.S. issuers in 2020. In addition to the 31 filings brought in SDNY, four suits that were initially brought in the Eastern District of New York, Central District of California and District of Oregon were subsequently transferred to SDNY. After the Second Circuit, the Third and Ninth Circuits had the most lawsuits with 22 and 15 filings respectively.

- The majority of suits were filed against companies headquartered in China (28) and Canada (12). Notably, a lawsuit was also filed against the nation of Ecuador.

- While the suits cover a diverse range of industries, the majority of the suits involved biotechnology and medical equipment (14), four of which were against companies with headquarters in Canada. Of the 28 complaints filed against companies headquartered in China, 22 of these complaints were brought against companies incorporated in the Cayman Islands.

Substantive Trends

An examination of the 2020 cases reveals three general trends, with securities class actions brought against companies who were alleged to have:

- misrepresented their prospects of approval by or compliance with U.S. regulatory agencies;

- misrepresented or omitted material information from proxy or solicitation statements in connection with a merger or acquisition; and

- failed to register under applicable federal and state securities laws in connection with the sale of cryptocurrency tokens.

Misrepresentation of Regulatory Compliance

Continuing the trend from 2019, the largest number of 2020 cases were filed against companies in the biotechnology and medical equipment industries. A significant number of these suits were based on allegations relating to the non-U.S. issuer’s approval by or compliance with U.S. regulatory agencies.

For example, several of the lawsuits alleged that defendants misrepresented their prospects of approval by the FDA. Two such complaints were brought against Canadian medical companies. In Kevin Alperstein, et al. v. Sona Nanotech Inc., et al., the plaintiffs alleged that the defendant, a Canadian medical supplier, made positive press statements about its COVID-19 rapid detection antigen test, which were unfounded as the FDA would deprioritize Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) approval of the test, finding it did not meet “the public health need” criterion. The statements also misrepresented that it was reasonable for Sona to believe that data gathered over such a short period of time would be sufficient for approval of its antigen test. As such, the plaintiffs alleged that the company violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act when it failed to disclose that it would have to withdraw its submissions for Interim Order authorization from the Canadian government as they lacked sufficient clinical data to support approval. Likewise, in In re Neovasc Inc. Securities Litigation, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendant, a Canadian medical device company, violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act when it failed to disclose to investors that the results of its clinical study for a cardiovascular device contained imbalances in missing information present in the control group versus the treatment group. According to the plaintiffs, this meant that control subjects were aware of their treatment assignment (i.e., they were not blinded), and, as a result, the FDA was unlikely to approve the company’s pre-market approval application for the device without additional clinical data.

Other regulatory-based lawsuits alleged that the non-U.S. issuer misrepresented their compliance with the FDA or other federal agencies. For example, in Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi, et al. v. Mylan N.V.,et al., the plaintiffs alleged that Dutch defendant Mylan, one of the largest generic drug manufacturers in the United States, violated Sections 14(a) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act by issuing multiple false and misleading public statements describing the company’s robust and comprehensive quality control processes, when in reality, the defendant’s chemists had manipulated quality control test data in order to achieve passing quality control results. Specifically, as alleged in the complaint, the FDA had investigated the company’s largest manufacturing plant and found significant deficiencies in its cleaning processes, numerous instances of a lack of oversight, and multiple instances of chemists re-cleaning and re-swabbing quality control testing machines until passing results were obtained.

Outside of the FDA sphere, the plaintiffs in Lee Wenzel, et al. v. Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, et al., alleged that the defendant, a Cayman semiconductor company, headquartered in China, failed to disclose in its public statements that there was an unacceptable risk that equipment supplied to the company would be used for military purposes and that the company was therefore foreseeably at risk of facing export restrictions by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The plaintiffs further alleged that the defendants violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act by failing to disclose that, as a result of the aforementioned risk, certain of its suppliers would need “difficult-to-obtain” individual export licenses. Similarly, in Neil Darish, et al. v. Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., et al., the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants, a Canadian mining company and certain officers, violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act by allegedly issuing false and misleading financial reports filed with the Canadian Securities Exchange and relatedly false and misleading press releases in connection with a mineral property project. The plaintiffs alleged that such public statements were misleading in that they failed to disclose that the project was contrary to Clean Water Act guidelines as it would be larger in duration and scope than conveyed to the public. As a result, the plaintiffs alleged, the defendants failed to disclose that the company’s permit application would be denied by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Misrepresentations in Connection with Mergers and Acquisitions

A significant percentage of the 2020 cases alleged violations of the securities laws based on a failure to disclose material information in connection with a non-U.S. issuer’s proposed merger or acquisition. Notably, over half (11) of these lawsuits were later voluntarily dismissed.

Nearly a third of these lawsuits—all filed in the District of Delaware and all voluntarily dismissed before a lead plaintiff was appointed-involved allegations that the non-U.S. issuer failed to disclose whether the company entered into any NDAs containing standstill or “don’t ask, don’t waive” provisions that prevented counterparties from requesting submitting offers. That was the case in Eric Sabatini, et al. v. Central European Media Enterprises Ltd., et al., where the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants, a Bermudan media and entertainment company, filed a misleading proxy statement regarding a plan of merger between the defendants and another cable company in violation of Sections 14(a) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act. In Sabatini, the plaintiffs alleged the defendants omitted material information regarding the engagement of the company’s additional financial advisor as well as the analyses performed by the company’s initial financial adviser.

They further alleged that the defendants failed to disclose whether the company entered into any nondisclosure agreements that contained standstill and/or “don’t ask, don’t waive” provisions that were preventing counterparties from submitting offers to acquire the company. Likewise, in John Thompson, et al. v. Gilat Satellite Networks Ltd., et al., the plaintiffs alleged, among other things, that the Israeli defendant Gilat, a satellite-based broadband communications company, filed a Registration Statement that omitted material information, including whether Gilat entered into any confidentiality agreements that contained standstill and/or “don’t ask, don’t waive” provisions that prevented counterparties from submitting offers to acquire the company, in violation of Sections 14(a) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act. Finally, in John Thompson, et al. v. Qiagen N.V., et al., brought by the same plaintiffs and law firm as in Gilat, the plaintiffs alleged that the Cayman defendants violated Sections 14(a) and 20(a) because their Registration Statement failed to disclose whether the confidentiality agreement executed during the go-shop period contained a standstill and/or “don’t ask, don’t waive” provision.

Other merger & acquisition-related suits alleged that non-U.S. issuers failed to disclose the existence of ongoing negotiations or proposals for subsequent transactions, which in turn caused investors to accept the pending buyout or acquisition at unfair prices. In In re E-House Securities Litigation,14 the plaintiffs alleged that E-House, a Cayman real estate company with its principal place of business in China, failed to disclose that throughout the course of a pending merger, the company was also pitching higher transaction projections to private investors in order to solicit those investors to participate in a subsequent post-merger transaction. The plaintiffs alleged these private projections were made at the same time that E-House was soliciting public investors and that the private projections were far more favorable to the company, as they showed the company had outperformed and was projected to continue outperforming. Therefore, the plaintiffs alleged that E-House defrauded investors by deceiving them into accepting a management buyout at an unfairly low price, in violation of Sections 10(b) and 13(a) of the Exchange Act. Another Cayman defendant headquartered in China was sued in Altimeo Asset Management, et al. v. Jumei International Holding Limited, et al., where the plaintiffs alleged that during a buyout process for Jumei’s outstanding shares, management failed to disclose in their offering and recommendation statements that Jumei was engaged in negotiations for the company to be acquired by one of its biggest competitors. The plaintiffs alleged that as a result, the defendants’ statements in connection with the pending buyout that they were unable to raise sufficient financing to support operations (which supported its advisors’ valuation of the company) were patently false and caused the company to be undervalued, in violation of Sections 10(b), 14(e) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act.

Misrepresentations Concerning the Sale of Blockchain Assets

Finally, while they did not constitute an exceedingly large number of the 2020 cases, the past year saw a relatively new development in lawsuits relating to non-U.S. issuers’ sale of blockchain or “crypto” assets. Seven securities lawsuits—brought primarily against Swiss or Singaporean entities—alleged violations of the securities laws in connection with the solicitation and sale of cryptocurrency tokens through and subsequent to Initial Coin Offerings (“ICOs”). These lawsuits were generally premised on allegations that defendants:

- failed to disclose that the tokens sold in connection with an ICO were indeed securities;

- misrepresented the value and utility of such tokens; and

- failed to register such tokens under United States securities laws.

Importantly, the plaintiffs in these cases relied on the argument that investors would not have known that the tokens issued in these ICOs were not securities because the solicitations and sales were made before April 2019, when the SEC issued its detailed framework to investors on how to determine whether the offers and sales of digital assets are in fact securities transactions. Unsurprisingly, the Southern District of New York was the court of choice for these blockchain-related lawsuits.

For example, in Timothy C. Holsworth, et al. v. BProtocol Foundation, et al., the plaintiffs alleged that the defendant Bancor, a Swiss entity headquartered in Israel, made numerous false statements and omissions in violation of Sections 5 and 12(a) of the Securities Act, both in public interviews and in a series of white papers published in connection with the company’s single-day ICO, which led investors to believe that the BNT tokens sold in connection with the ICO were not securities, but rather de-centralized and already functional crypto-assets. In Corey Hardin, et al. v. Tron Foundation, et al., the plaintiffs alleged that Singaporean defendant TRON also violated Sections 5 and 12(a) of the Securities Act when it misrepresented to investors that its TRX token was built on an independent blockchain and as such was subject to new voting mechanisms, when in reality, the TRX token was simply a smart contract built on the existing Ethereum block-chain and not part of an independent block-chain. Finally, in Brett Messieh, et al. v. KayDex Pte. Ltd., et al., the plaintiffs alleged that Singaporean software company Kyber Network violated Sections 5 and 12(a) of the Securities Act when it issued a whitepaper which misleadingly likened the company’s “KNC token” to bitcoin and ether, and expressly stated that its protocol that relied on the KNC token would allow “instant exchange and conversion of digital assets (e.g., crypto tokens) and cryptocurrencies (e.g., Ether, Bitcoin, ZCash) with high liquidity.” The plaintiffs pointed to the fact that the company failed to file an SEC registration statement for the KNC tokens as further proof that the company intended to convey to investors that the tokens were not securities.

Motion to Dismiss Decisions

Compared to 2019, 2020 saw relatively no change in the number of dispositive decisions issued in securities fraud cases against non-U.S. issuers. In 2020, courts rendered eight dispositive decisions on cases filed in 2018 and 2019, and, in early 2021, one dispositive decision was rendered with respect to a 2018 case. Of the eight decisions rendered in 2020 with respect to 2018 and 2019 filings, six of the securities class actions were filed in the Southern District of New York.

While it is hard to discern trends from just nine dispositive decisions, the courts’ reasoning for dismissing cases is still instructive for the non-U.S. issuers who find themselves the subject of class actions lawsuits. Courts generally dismissed complaints:

- relating to China-based, Cayman incorporated companies that went private and later relisted;

- for failing to allege a domestic transaction underlying a Section 10(b) claim;

- for failing to plead fraud relating to financial issues;

- for being time-barred, and

- for lacking personal jurisdiction.

Going-Private Transactions Relating to China-Based Companies

Another trend in 2020 was the dismissal of three cases involving China-based companies that went private and then subsequently relisted on another public exchange. For example, in Altimeo Asset Management v. Qihoo 360 Technology Co. Ltd., the court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss with prejudice. In Qihoo, former ADS holders of the Cayman Island-incorporated, Chinese headquartered company filed claims under Sections 10(b), 20(a) and 20A of the Exchange Act, alleging that the proxies relating to a going-private transaction were false or misleading because they purportedly concealed a secret plan to relist the surviving company once the merger was completed despite the fact that the proxies disclosed the possibility of a future relisting. In granting the defendants’ motion to dismiss, the court found that the plaintiffs did not adequately allege material misrepresentations or omissions by the defendants, a required element of a Section 10(b) claim. The court pointed out that each of the alleged misstatements and omissions were alleged to be false for the same reason: the statements failed to inform shareholders of Qihoo’s alleged plan to relist on the Chinese stock exchange a year and a half after the merger. The court then focused its inquiry on whether the plaintiffs had adequately pleaded that such a plan existed at the time the statements were made. After analyzing the allegations relying on a confidential witness and various news articles, the court concluded that the plaintiffs failed to plead adequately particularized allegations to satisfy the PSLRA.

In addition to Qihoo, courts also ruled in favor of China-based Cayman Islands-incorporated companies in ODS Cap. LLC v. JA Solar Holdings Co. Ltd. and Altimeo Asset Mgmt. v. WuXi PharmaTech. In ODS Cap. LLC v. JA Solar Holdings Co. Ltd.,the same lead plaintiffs, ODS Capital and Altimeo Asset Management, brought a suit against a Cayman Islands company that relisted on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange three days after going private in a merger transaction. The court dismissed the complaint. Similarly in Altimeo Asset Mgmt. v. WuXi PharmaTech, a case the court described as “on all fours with Qihoo” with “nearly identical claims brought by [the same lead plaintiff]”, a Cayman Islands company went private in a merger and, over a year and a half later, relisted the surviving entities on the Hong Kong and Shanghai Stock Exchanges at higher valuations. The court explained that the plaintiffs must plead particularized factual allegations that are sufficient “to support a plausible inference that [the company] had concrete plans to relist before the merger.” Because they failed to do so, the court dismissed the claims.

Failure to Allege a Domestic Transaction

Recently, the Second Circuit reaffirmed that the federal securities laws do not apply to “predominantly foreign” securities transactions, even if they might take place in the United States. As background, the Supreme Court’s decision in Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd. closed the door on plaintiffs bringing “F-cubed” cases-whereby foreign investors sue a foreign issuer in the United States based upon a security traded on a foreign exchange. Courts and litigants continue to grapple with the scope of Morrison.

In Cavello Bay Reinsurance Ltd. v. Shubin Stein et al., the plaintiff-appellant Cavello Bay Reinsurance Ltd. bought shares in a Bermudan holding company, Spencer Capital Ltd. (“Spencer Capital”), which operated out of New York and invested in U.S. insurance services. The plaintiff alleged that Spencer Capital’s pitch deck for the offering represented that a management fee to a third party, a Delaware entity owned by the defendant-appellee Kenneth Shubin Stein, was tied to Spencer Capital’s profits when in fact, the fee was tied to the company’s book value. The district court dismissed the suit on two independent grounds:

- the parties’ transaction was not “domestic” under Absolute Activist Value Master Fund v. Ficeto; and

- even if the transaction was domestic, the plaintiff’s claims were impermissibly “predominantly foreign” under Parkcentral Global HUB v. Porsche Automobile Holdings SE.

The Second Circuit affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the plaintiff’s claims of securities fraud for failure to plead a domestic application of the law. In its reasoning, the Second Circuit highlighted the fact that the claims were based on a private agreement for a private offering between both a Bermudan investor and a Bermudan issuer and that the plaintiff purchased restricted shares in Spencer Capital in a private offering. Notably, the shares reflected only an interest in Spencer Capital and were not listed on any U.S. exchange, nor were they otherwise traded in the United States. The court noted that the main link to the United States was the subscription agreement’s restriction clause which would require the plaintiff to register the shares with the SEC, or meet an exemption, if the plaintiff wished to resell them. However, the court explained that the clause operated only as a contractual impediment to resale. Accordingly, the court found that the plaintiff failed to plead a domestic application of Section 10(b), and, since the plaintiff did not challenge the decision to dismiss its Section 29(b) and Section 20(a) claims, the court affirmed the entire judgment.

Failure to Plead Fraud Relating to Financial Issues

In 2020, courts dismissed claims that failed to allege fraud relating to company financial issues, including claims of alleged misstatements relating to financial performance and sustaining dividends, as well as alleged misstatements in company financial statements.

In Jam-Wood Holdings LLC v. Ferroglobe PLC, the court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss in full because the complaint failed to plead the elements of falsity and scienter relating to allegations of violations of Section 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act. In Ferroglobe, the plaintiff alleged that the defendants, which included the company incorporated in the UK and its officers, made material misrepresentations or omissions from September 4, 2018 until November 26, 2018 regarding the health of Ferroglobe’s silicon-metals business in an effort to conceal the company’s poor financial results from that quarter. The court found that the plaintiff’s complaint only alleged scienter in a conclusory fashion and was devoid of any allegations that the defendants acted with any motive to deceive the investing public. For example, the court noted that the plaintiff did not specify what information the defendants possessed, nor how or when they received such information. In addition, the court found “too speculative” the plaintiff’s general allegation that the individual defendants, by virtue of their positions as officers of the company, must have known the true facts of the company’s financial performance as reflected in the company’s September 2018 and November 2018 statements.

In addition, in In re Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV Securities Litigation, the plaintiff alleged that the defendants, who were incorporated in Belgium, committed fraud because they expressed the goal of sustaining their dividend and described how the company was on track to attain that goal, only to instead cut the dividend. The plaintiff alleged the material omissions included information about financial challenges that would restrict the dividend, such as currency volatility, credit rating pressure, input cost inflation, and cash flow. The court found the complaint insufficient to plead fraud because it failed to satisfy the heightened pleading requirements set forth in the PSLRA, as the defendants’ statements fell under the PSLRA’s safe harbor provision for certain “forward-looking statements.” The court also noted that for the alleged misleading statements that arguably fell outside of the safe harbor, the plaintiff failed to allege how those statements were false or misleading.

The court further stated that even if the plaintiff had adequately plead actionable misstatements, their Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 claims would nevertheless fail due to insufficient pleading of scienter. The court found that the plaintiff failed to establish strong circumstantial evidence of conscious misbehavior or recklessness because the complaint’s principal allegations were vague and insufficient, and noted that courts routinely reject pleadings of scienter that are based on allegations regarding defendants’ board membership, executive managerial positions, and access to information regarding a company’s financial outlook. Accordingly, the court dismissed the complaint.

Lastly, in Danske, the court granted Danish defendant Danske Bank’s (“DB”) motion to dismiss with prejudice. The plaintiffs alleged that DB and its local banking branch in Estonia engaged in the largest money laundering scandals to date; specifically, between 2008 and 2016, they alleged that US$230 billion was illegally laundered through DB. The plaintiffs’ claims concerned alleged misrepresentations about DB’s financial condition given extensive breakdowns in anti-money laundering controls at DB’s Estonian branch between approximately 2007 and 2015, as well as subsequent fallout from the discovery of the lapses.

The court found that the plaintiffs failed to plead fraud with particularity as required under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) and the PSLRA, failed to plead a material misrepresentation or omission, and failed to plead a strong inference of scienter. In dismissing the plaintiffs’ fraud claim for failing to meet the heightened pleading standards of Rule 9(b) and the PSLRA, the court reasoned that the plaintiffs’ complaint used “two terse paragraphs generically to allege why pages of quotations spanning 83 paragraphs contain false or misleading statements.” The court pointed out that the plaintiffs’ theory of fraud in their opposition papers only advanced six claims, implicating less than a third of the complaint’s alleged misstatements. Moreover, the plaintiffs pointed to a single paragraph with a specific allegation of fraud, which, “when read liberally, describes why the defendants’ statements in the preceding four paragraphs are alleged to be false or misleading.”36 The court stated that this single paragraph did not rescue a vast majority of the alleged misstatements alleged in the complaint, but rather, revealed that the plaintiffs knew how to allege fraud with specificity but had chosen not to do so within the majority of the complaint. Thus, the court found the plaintiffs failed to allege a materially false or misleading statement that could sustain a securities fraud claim.

Finally, the court held that the plaintiffs failed to plead scienter because they did not identify any motive to deceive or defraud, nor did they raise a strong inference that the defendants acted recklessly or with conscious disregard of the truth. The court found that the plaintiffs alleged, in a conclusory manner, that the defendants and employees of DB received reports contradicting public statements, while failing to connect any of those reports to specific representations by specific persons during the relevant time periods.

Time-Barred Claims and Lack of Personal Jurisdiction

In Fedance v. Harris et al., the plaintiff alleged that the defendants engaged in sales of unregistered securities through an ICO and sale of their tokens. The court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss on the basis that the plaintiff’s 12(a)(1) claims were time-barred by the one-year statute of limitations and were not subject to equitable tolling.

Finally, in Amann v. Metro Bank PLC,38 the plaintiff alleged that the defendants, incorporated in the U.K., made false and/or material misstatements regarding the company’s capital ratios. The court dismissed the case due to lack of personal jurisdiction, stating that both defendants were non-U.S. residents who were based in the United Kingdom, and that the plaintiff had not alleged any evidence establishing the defendants’ contacts with the United States.

Conclusion

There is no question that even during a global pandemic, non-U.S. issuers remain targets of securities class action suits regardless of whether the challenged conduct occurred abroad. A company does not need to be based in the United States to face potential securities class action liability in U.S. federal courts. As such, it is imperative that non-U.S. issuers take steps to mitigate their risks in not only their home jurisdictions but also in the United States.

Non-U.S. issuers should be particularly cognizant when making disclosures or statements to:

- speak truthfully and to disclose both positive and negative results;

- ensure that a disclosure regimen and processes are well-documented and consistently followed;

- work with counsel to ensure that a disclosure plan is adopted that covers disclosures made in press releases, SEC filings and by executives; and

- understand that companies are not immune to issues that may cut across all industries.

Non-U.S. issuers should work with the company’s insurers and hire experienced counsel who specialize in and defend securities class action litigation on a full-time basis. Lastly, to the extent that a non-U.S. issuer finds itself the subject of a securities class action lawsuit, the bases upon which courts have dismissed similar complaints in the past can be instructive.

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print