Huazhi Chen is Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Notre Dame’s Mendoza School of Business; Lauren Cohen is the L.E. Simmons Professor in the Finance & Entrepreneurial Management Units at Harvard Business School; and Umit G. Gurun is the Ashbel Smith Professor at the University of Texas at Dallas. This post is based on their recent paper.

Information acquisition is costly for investors—the exact cost of which depending on timing, location, a person’s private information set, etc. To this end, delegated portfolio management is the predominant way in which investors are being exposed to both equity and fixed income assets. With over 16 trillion dollars invested, the US mutual fund market, for instance, is made up of over 5,000 delegated funds and growing. While the SEC has mandated disclosure of many aspects of mutual fund pricing and attributes, different asset classes are better (and worse) served by this current disclosure level. Investors have thus turned to private information intermediaries to help fill these gaps.

In our paper, we show that for one of the largest markets in the world, US fixed income debt securities, this has led to large information gaps that have been filled by strategic-response information provision by funds. The reliance on (and by) the information intermediary has resulted in systematic misreporting by funds. This misreporting has been persistent, widespread, and appears strategic—casting misreporting funds in a significantly more positive position than is actually the case. Moreover, the misreporting has a real impact on investor behavior and mutual fund success.

Specifically, we focus on the fixed income mutual fund market. The entirety of the fixed income market is similarly sized to equites (e.g., 40 trillion dollars compared with 30 trillion dollars in equity assets worldwide). However, bonds are both fundamentally different as an asset cash-flow claim, along with having different attributes in delegated portfolios. While equity funds hold predominantly the same security type (e.g., the common stock of IBM, Tesla, etc.), each of a fixed income funds’ issues differ in yield, duration, covenants, etc.—even across issues of the same underlying firm—making them more bespoke and unique. While the SEC mandates equivalent disclosure of portfolio constituents for equity and bond mutual funds, this data is more complex in both processing and aggregating to fund-level measures for fixed income.

This has led information intermediaries to bridge this gap, providing a level of aggregation and summary on the general riskiness, duration, etc. of fixed income funds upon which investors rely. We focus on the largest of such intermediaries that provides data on categorization and riskiness at the fund level—Morningstar, Inc. In particular, we compare fund profiles provided by the intermediary (Morningstar) to investors against the funds’ actual portfolio holdings. We find significant misclassification across the universe of all bond funds. This results in up to 31.4% of all funds in recent years and is pervasive across the funds being reported as overly safe by Morningstar.

How do these misclassifications occur? Morningstar “rates” each fixed income mutual fund into style boxes based their assessment of credit quality and interest rate sensitivity. For instance, a bond portfolio could be designated as a high credit quality fund with limited interest rate sensitivity. In addition, Morningstar places each fund into a category such as “Multisector Bond,” or “Intermediate Core Bond.” Within each of these fund categories, through a fund’s realized returns and volatility Morningstar then ranks and gives an aggregate rating in the form of “Morningstar Stars.”

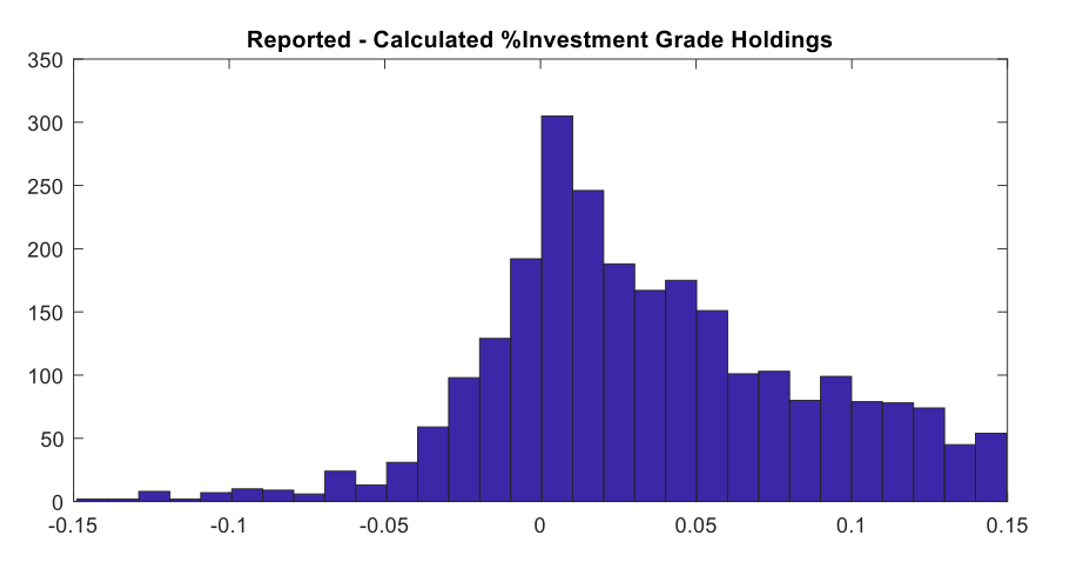

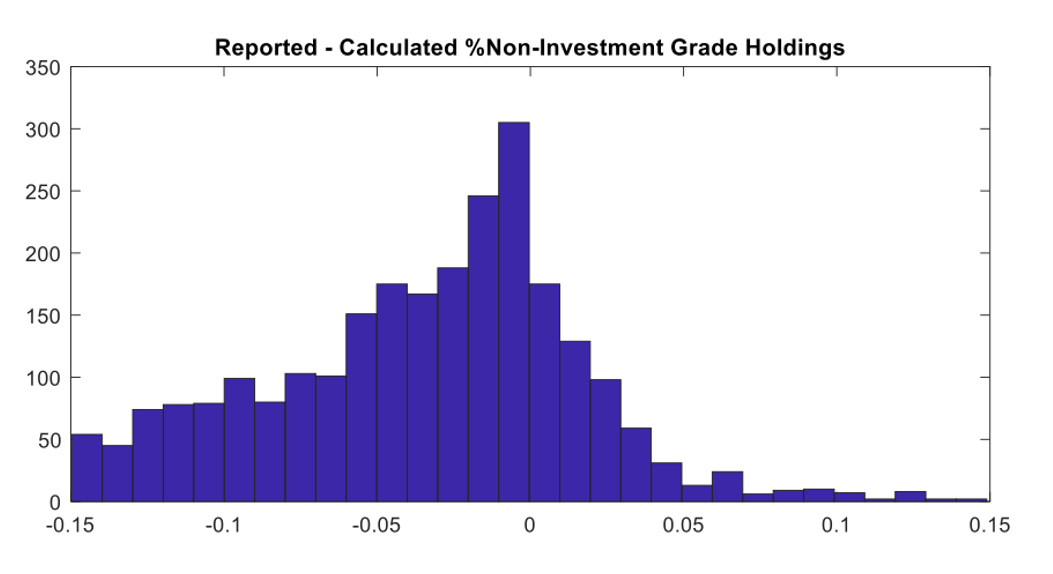

The central problem that we show empirically, however, is that Morningstar itself has become overly reliant on summary metrics, leading to significant misclassification across the fund universe. Morningstar requires data provision from each fund it rates (and categorizes) on the breakdown of the bonds the fund holds by risk rating classification. Specifically, what percentage of the fund’s current holdings are in AAA bonds, AA bonds, BBB bonds, etc. One might think that Morningstar uses these self-reported “Summary Report,” data sent to it by funds to augment the detailed holdings it acquires from the SEC filings on the fund’s holdings. However, Morningstar makes credit risk-summaries solely based on this self-reported data. In the below figures, we present the histogram of the gap between fund reported percentage holdings and the calculated percentage of holdings in the various bond credit rating categories. Ideally, if Morningstar and the bond funds in its database kept the same reporting standards in credit ratings, the fund reported percent should be almost same as the calculated percent holdings. Therefore, these histograms should report a sharp spike around zero (e.g., no discrepancies), and exhibit no significant variation. Figure 1 and 2 shows that, on the contrary, there is a wide dispersion of discrepancies between the records of asset compositions. Most notably, for assets above investment grade (above BBB), the percentage of assets reported by funds is markedly higher than the percentage of assets calculated by Morningstar (Figure 1). When we check the same gap for below investment grade and especially in unrated assets, we see an opposite pattern: the percentage of assets reported by funds is significantly lower than the percentage of assets calculated by Morningstar (Figure 2)

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

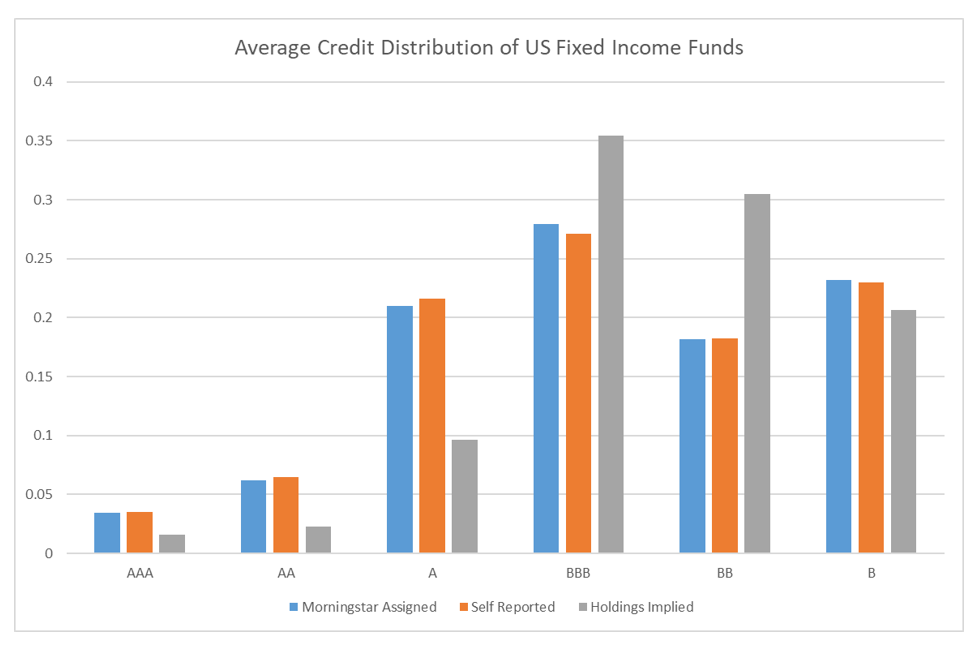

Our evidence suggests that funds on average report significantly safer portfolios than they actually (verifiably) hold. Funds report holding significantly higher percentages of AAA bonds, AA bonds, and all investment grade issues than they actually do (Figure 3). For some funds, this discrepancy is egregious—demonstrably with large holdings of non-investment grade bonds, despite being rated AAA portfolios. Due to this misreporting, funds are then misclassified by Morningstar into safer categories than they otherwise should be.

Figure 3.

So, what are the characteristics of these “Misclassified Funds?” First, Misclassified Funds have higher average risk—and accompanying yields on their holdings—than its category peers. This is not completely surprising, as again Misclassified Funds are holding riskier bonds than the correctly classified peers in their risk category. Importantly, this translates into significantly higher returns earned on-average by these Misclassified Funds relative to peer funds. They earn 3.04 basis points (t=3.47) per month more, implying a 16% higher return than peers.

To estimate what portion of this seeming return outperformance of Misclassified Funds comes from skill versus what comes from the unfair comparison to safer funds, we turn to the funds’ actual holdings reported in their quarterly filings to the SEC. We use these actual holdings to calculate the correct risk category that the fund should be classified into were it to have truthfully reported the percentage of holdings in each risk category. When we analyze the performance using proper peer-comparisons, we find that Misclassified Funds no longer exhibit any outperformance. Misclassified Funds reap significant real benefits from this incorrectly ascribed outperformance. Furthermore, we find that, after controlling for Morningstar category and risk classification, Misclassified Funds are assigned more Morningstar Stars. Armed with higher returns relative to (incorrect) peers and higher Morningstar Ratings, Misclassified Funds then can charge significantly higher expenses.

We believe that our study is a first step to think about a market design in which information intermediaries have more aligned incentives to better process and deliver the information they gather from market constituents. Future research should explore alternate monitoring and verification mechanisms for the increasingly complex information aggregation in modern financial markets, along with ways that investors can engage as important partners in information collection and price-setting.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print

One Comment

Outstanding research.