Anna Hirai is Co-Head of ESG Research and Andrew Brady is Senior Analyst at SquareWell Partners. This post is based on their SquareWell memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here); and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

I. Introduction

Assets in sustainable funds hit a record high of USD 1,258 billion as of the end of September 2020, with Europe surpassing the USD 1 trillion mark according to Morningstar’s research. The increased integration of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors into investment decision-making, whether it be for active or passive investment styles, has made the quality and availability of well-structured and digestible data provided by ESG rating and data agencies ever more important.

The growing influence of ESG data and ratings on the allocation of capital will undoubtedly bring with it increased scrutiny. Two main areas that have drawn media attention and investor criticism towards ESG ratings providers are: (1) their focus on past performance and lack of predictive value over future performance; and (2) the sometimes-diverging opinions of ESG ratings providers for the same

company.

The lack of global reporting standards and agreement on what should be deemed as material for each sector has led to ESG data and ratings providers each adopting their own methodologies and processes, making it difficult for companies to manage their narrative on sustainability and determine

how best to allocate internal resources regarding sustainability reporting. Further complicating the landscape for companies is the fact that a growing number of investors are developing their own ESG ratings by leveraging multiple data sources.

Given the increasing importance of ESG data and ratings, for this Progress Group SquareWell Partners (“SquareWell”) interviewed representatives from companies, institutional investors, ESG ratings and data providers, and academia. We have split the Progress Group report into two sections

where we provide: (1) an overview of the ESG data and ratings landscape; and (2) key takeaways for companies to navigate this increasingly complex market force.

II. ESG Data and Ratings Providers

A. The Playing Field

The rise of ESG’s importance in investment decision-making has unsurprisingly presented a market opportunity for a growing number of players to emerge to service this need. According to ERM, there were close to 600 ESG ratings and rankings recorded as of 2020 (see Table 1 for a summary of key players within the ESG data and ratings space). Whilst new players are emerging, financial services firms are consolidating the larger players under their brands. Notable examples include:

- ISS’s acquisition of Oekom Research in 2018 (source)

- MSCI’s acquisition of GMI Ratings in 2014 (source) and Carbon Delta in 2019 (source)

- Moody’s acquisition of Vigeo Eiris (V.E) in 2019 (source)

- S&P’s acquisition of Trucost in 2016 (source) and the ESG rating business of RobecoSAM in 2019 (source)

- Morningstar’s acquisition of Sustainalytics in 2020 (source)

- Deutsche Börse’s acquisition of ISS in 2020 (source)

ESG passive investment strategies often employ benchmarks offered by major index providers (such as MSCI, S&P, etc.) who are supported by ESG data and ratings providers. Since the creation of the first ESG index in 1990, called the Domini 400 Social Index (now called the MSCI KLD 400 Social Index), there has been a dramatic expansion of ESG indices, with more than 1,000 ESG indices in 2020 according to USSIF. In Table 2, SquareWell mapped out ESG ratings and data providers servicing the 40 ESG Exchange-Traded Funds (ETF) that have assets in excess of $1 billion as of 31 December 2020. Although most funds are domiciled in Europe, the geographic focus of most of these investment products is the US (see Appendix for a full breakdown).

The ways in which investors use such ratings and the underlying ESG data has become increasingly complex in recent years, whether it is to integrate ESG within their general investment decision-making process, impact investing, exclusion/ negative screening, engagement, etc.

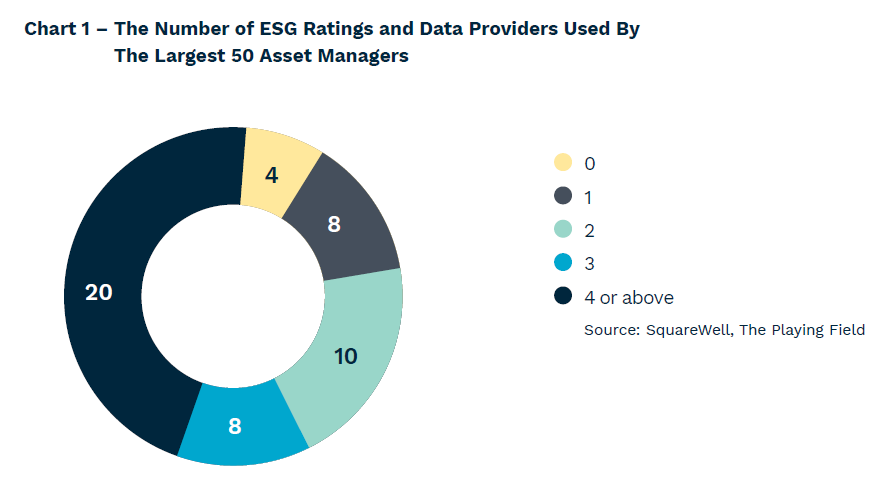

According to SquareWell’s latest study, The Playing Field, 38 of the top 50 asset managers use two or more ESG data and ratings providers. The most preferred ESG data and ratings providers are: MSCI, Sustainalytics, ISS-ESG and Vigeo Eiris (“V.E”).

B. How Is It Possible to Have Different Ratings for the Same Company?

Most of the ESG ratings and data providers, including MSCI and Sustainalytics, make publicly available the overall scores assigned to companies they cover. This increased transparency undoubtedly paves the way for market participants to scrutinize their approach, with the focus being on: (1) the differences across firms on what ESG factors are considered material, (2) the measurement of ESG factors, (3) the weight given to ESG factors, and (4) the sources used to carry out the evaluation.

The lack of consistency amongst the ESG data and ratings providers has been an area of academic focus. According to “Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings” co-authored by Florian Berg of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management (“MIT”), also one of the participants of this Progress Group, together with two other academics (Julian Fritz Kölbel and Roberto Rigobon), they attribute the divergence of ESG ratings into three sources: (1) different scope of categories; (2) different measurement of categories; and (3) different weights of categories.

- Scope Divergence takes place when companies are not assessed on the same set of ESG factors, thereby leading to different overall scores for rated companies. For instance, rating agency “A” may evaluate a company’s ESG performance by covering 10 ESG factors whilst rating agency “B” may have a more comprehensive approach and analyze 20 ESG factors for the same company. Scope divergence may become more pronounced for companies with diversified business operations where they may be classified under different industries by different ESG rating agencies. As ESG rating agencies often employ different industry classification systems (e.g. GICS, ICB, SICS etc.), a company’s set of material ESG topics, selected based on the industry classification and evaluated within the rating framework, could vary from one rating agency to another. Xavier Houot, Group Chief Environmental Sustainability Officer of Schneider Electric, and Tjeerd Krumpelman, Global Head of Business Advisory, Reporting and Engagement of ABN AMRO Bank, both note that the ratings framework often includes a topic or indicator that may not be very relevant for their respective companies.

- Measurement Divergence was found to be the most important contributor by MIT’s research to the overall score divergence amongst ESG ratings providers. While a company’s sustainability performance may be assessed on the same set of ESG issues, the indicators used may vary by ratings provider. As an example, Cristina Daverio, Head of ESG Research at V.E mentions that both employee turnover and the number of labor-related litigations capture aspects of human capital management, but if only one or the other is used, this will likely lead to different assessments. In research conducted by Research Affiliates, it was revealed that Wells Fargo’s fake account scandal was treated as a “Business Ethics” issue under the Governance pillar by one rating agency while another treated it as an issue related to “Information to Customers” under the Social pillar.

Florian Berg explains that the Governance score showed the highest variation among different ESG ratings providers in comparison to the Environmental or Social pillars, suggesting that different ESG rating agencies disagree on what “good governance” looks like or how it should be measured. Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson of PGIM Fixed Income adds that the evaluation of a company’s governance should include a review of the individuals upholding the company’s governance structure; a focus on only the governance structures may result in the substance of governance being overlooked. According to Unanyants-Jackson, such comprehensive review can only be achieved through fundamental analysis and direct engagement with companies.

- Weighting Divergence occurs when input data or certain topics are allocated more weight than others, reflecting diverging views on the materiality of these factors. Schneider Electric’s Xavier Houot points out that there should be more weight on output-based indicators (outside of management’s control) than input-based indicators (within management’s control) to truly measure a company’s impact. For instance, the number of training hours on corruption may not correlate with a lower number of corruption cases. Focusing on the overall impact, argues Xavier Houot, may be more useful in measuring companies’ sustainability as the market matures.

C. Unique Data and Ratings for Different Outcomes

While the media has frequently portrayed this lack of unanimity between ESG ratings as a concern, all interviewees do not see this divergence as problematic, but rather see it as the “added value” of each ESG data and ratings provider. Carole Crozat, Head of Thematic Research, Sustainable Investments at BlackRock, acknowledges that “divergence will happen when you go from fact to opinion, fact is data and opinion is what data to consider and what weight you will give”. Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson of PGIM Fixed Income notes that “understanding what the ESG ratings providers are trying to measure is important as that’s where the differences come from”.

Howard Sherman, an Executive Director at MSCI ESG Research, and Keeran Gwilliam-Beeharee, an Executive Director and Head of Market Access at V.E agree that differences in methodologies are their value proposition and will continue to remain proprietary. Keeran Gwilliam-Beeharee noted that “disagreement can be healthy, as long as the underlying assumptions are explained”. The consensus seems to be that there is value in having different ESG ratings providers as they all bring different perspectives and answer different questions. What is important perhaps is not the overall ESG ratings but understanding the underlying data captured, weightings, and assumptions behind each ESG ratings providers’ methodologies.

Though the rating divergence may in itself not be the issue, it is important for companies to remember that these ratings are used to select constituents of ESG indices, which directs investment towards the selected companies (see Table 2). As such, it is important for companies to determine the main ESG data and ratings providers as well as spend time to understand their methodologies and the underlying datasets to ensure that they are capturing as much as possible the money that can be re-directed to the company through passive investment strategies.

Whilst all participants to the Progress Group support the variety of ESG data and ratings providers, there were contrasting views on how the ESG data and ratings market will evolve. Florian Berg of MIT predicts that the industry will continue to face further consolidation but hopes that this does not come at the expense of seeing new players specializing in one specific area with quality data. This view is shared by Carole Crozat of BlackRock who believes that major ESG data and ratings providers do not offer, for example, sufficient datasets on physical climate risks, which led to BlackRock forming a partnership with the Rhodium Group that specializes in quantifying localized physical impacts of climate change.

Hortense Bioy, Global Director of Sustainability Research at Morningstar, suggests that “different ratings answer different questions, but ideally an investor should look at both risk and impact when examining portfolio companies’ ESG profile.” She adds “in three to four years, we will probably talk less about ESG risks since they will have been integrated completely into investors’ analysis of companies in the mainstream investment process”. Similarly, PGIM Fixed Income’s Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson believes that there should be different types of ratings, with clarity on the focus of the underlying methodology, such as an ESG Impact rating, ESG Risk rating, SDG rating, and so on.

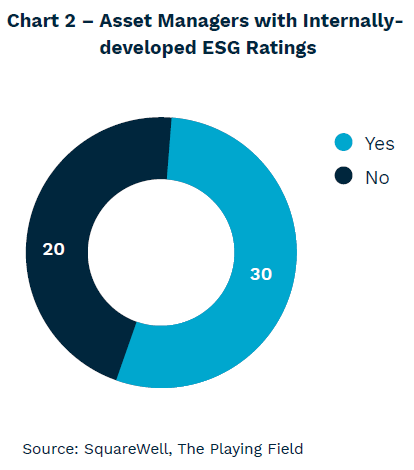

Carole Crozat of BlackRock suggests that “there is no perfect rating and investors are moving away from a singular rating and use engagements to add an overlay to individual company assessments”. V.E’s Cristina Daverio adds that investors’ demand for granular data that makes up an overall score has increased in recent years. Confirming Cristina Daverio’s view, a growing number of investors are also developing their own ESG ratings using the underlying datasets from these ESG data and ratings providers, screening criteria and assigning weights of ESG factors to distinguish themselves from their peers and generate excess returns. According to SquareWell’s latest study, The Playing Field, 30 of the world’s largest 50 asset managers have created their own proprietary ESG ratings, including Legal & General Investment Management, BNP Paribas AM and State Street Global Advisors. These internal ratings, of which some are made publicly available, are used as part of portfolio construction and management, as well as stewardship activities. Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson notes that raw data that feeds into ESG ratings often sends stronger signals on future performance than the overall ESG rating itself, which is only the starting point when analyzing a company’s ESG performance.

D. Emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Players like Arabesque and RepRisk are disrupting the ESG data market by leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). The automation of data screening and researching process has enabled these players to update their data more frequently than traditional ESG rating agencies that normally maintain an annual rating cycle. The traditional ESG ratings providers have also started leveraging new technologies, however. Tonmoye Nandi, Managing Director of ESG Data Operations at MSCI, states that they utilize technology and natural language processing to collect data and screen news and public information on an ongoing basis. The captured data is then subjected to a qualitative overlay by ESG research analysts to ensure the quality of the information captured as well as to assess the severity of corporate controversies screened.

A key difference between traditional ESG ratings providers and AI-driven ESG data providers is that the former opts for an “inside-out” approach while the latter adopts an “outside-in” approach. What this means is that traditional ESG ratings providers primarily rely on corporate disclosure amongst other data sources while AI-driven data providers focus more on external data sources such as media reporting. Whilst AI-based ESG data providers may offer solutions to some issues that are more common with traditional ESG rating agencies, such as frequency of data updates and company coverage, their approach also has downsides, such as a lack of transparency over the credibility of underlying data used in the assessment, with no data validation opportunity for companies.

E. Regulators’ Role in ESG Data and Ratings

ESG data and ratings providers are not regulated in the same way as credit rating agencies and financial intermediaries; however, this could change, at least in Europe. The financial authorities in France (the Autorité des Marchés Financiers, AMF) and in the Netherlands (the Autoriteit Financiele Markten, AFM) proposed in December 2020 a European regulatory framework for “sustainability-related service providers.” The proposal sets out various requirements for ESG rating providers, including transparency on methodologies, management of conflicts of interest for ratings providers serving both companies and investors, internal control processes, and enhanced dialogue with companies subject to ESG ratings.

The Progress Group’s participants’ views on the topic of regulation were varied. Tjeerd Krumpelman of ABN AMRO Bank does not believe that ESG ratings providers should be regulated, especially on their proprietary methodologies, Florian Berg of MIT, who was in discussion with AMF before the said paper was published, is in favor of regulating ESG rating agencies to make them more transparent, but agrees that methodologies should not be regulated as they need to evolve and improve over time. Carole Crozat of BlackRock did not comment on the need for regulation per se but stressed the importance of ensuring minimum quality standards for ESG ratings.

None of the interviewees of the Progress Group believes that the scope or measurement of ESG issues should be regulated. Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson of PGIM Fixed Income believes the market first needs to reach an agreement on what ESG means and how such factors should be measured and reported on before there is regulatory oversight. As sustainable investment industry and the ESG data market have evolved without much intervention from regulators, most participants’ ambivalence towards the role of regulators may not be surprising. However, all seem to agree that additional transparency from ESG ratings providers is critical.

How Should Companies Adapt

A. Like Everything, Materiality Evolves

With more than 10,000 reporters in over 100 countries, the world’s most widely used sustainability reporting standard, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), requests companies to disclose material ESG topics as well as disclose how these ESG topics were selected. GRI states in its GRI 101 standard that the materiality assessment should cover topics that “reflect the reporting organization’s significant economic, environmental, and social impacts” on stakeholders, indicating an outward-looking approach. In contrast, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), endorsed by investors representing more than USD 40 trillion in AUM, has developed a materiality map outlining material ESG topics for each industry. SASB’s view of materiality is defined as factors that could affect financial performance and enterprise value of the reporting company, thereby influencing investment or lending decisions.

These outward- and inward-impact approaches are in fact complementary and together aligned with the concept of “double materiality” applied by the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). Cristina Daverio of V.E explains that its own ESG rating methodology also incorporates the double materiality approach that “brings into consideration the impacts of ESG factors on the company (financial and operational risks) as well as the impact of the company on its stakeholders”.

A majority of participants agree that the concept of materiality should not be static and evolve over time. This also implies that companies should be wary of, and continuously monitor, changing stakeholder expectations and adjust its priorities when necessary. Nadia Laine, an Executive Director who is part of the ESG Research Product Management Team at MSCI, confirms that MSCI’s methodology is reviewed on an annual basis to account for changes in materiality. MSCI’s Nadia Laine explains that the process to update a methodology includes consultations with external stakeholders, including companies, and an analysis of quantitative data (close to 200 data points ranging from injury frequency rate to carbon emissions), which evaluates the level of risk exposures caused by key ESG factors in certain sectors.

Morningstar has amended its ratings methodology twice since 2016, while Sustainalytics changed its ESG assessment from a best-in-class approach to a risk-based approach in 2018, and MSCI recently updated its methodology to re-weight certain ESG topics. Whilst methodologies should be adapted to changing market trends and expectations, Hortense Bioy of Morningstar warns that with every change, it becomes difficult to do historical analyses and monitor companies’ progress. Carole Crozat of BlackRock states that ratings volatility stemming from a methodology update remains an issue for investors and underlines the importance of ESG ratings providers engaging with their clients when such a change happens.

From a company perspective, changing methodologies represents an issue. For example, Tjeerd Krumpelman of ABN AMRO Bank cites that a change in the methodology used to select constituents of the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (owned by S&P Global) led to significant score volatility, making it difficult for ABN AMRO Bank to track its sustainability performance over the years. Tjeerd Krumpelman underlines that while the change in methodology was carried out in a transparent manner, some investors may have focused solely on the revised rating and not pay attention to the underlying methodology change.

B. Materiality Hurdle Passed; How Do You Report?

An increasing burden on companies to disclose extra-financial information is evident as the length of annual, integrated, and sustainability-related reports only seems to get longer due to a variety of disclosure recommendations proposed by reporting standard setters as well as regulatory requirements. Xavier Houot of Schneider Electric and Tjeerd Krumpelman of ABN AMRO Bank are looking ahead and believe that it is better to start disclosing relevant ESG information requested by the different market participants rather than waiting for a common framework to be established. Tjeerd Krumpelman notes that “it takes a lot of time to adapt to a new reporting standard or framework, so monitoring where the reporting standards are going is important”.

As GRI, the most widely used sustainability reporting standard globally, requires its reporters to include a content index in a sustainability report, a short-term solution for companies to meet investor expectations on sustainability reporting would be to add a reference or content index citing the locations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) aligned disclosure and SASB metrics. From a company’s perspective, this approach can minimize the workload of disclosing additional information and is optimal considering some overlap between these initiatives. From a user perspective, this approach not only ensures the ease of accessing relevant sustainability-related information but also reduces the risks of rating analysts and investors missing crucial information.

The news of five reporting initiatives stating their intent to work together and the subsequent planned merger between SASB and International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) are steps in the right direction. The formation of a working group, as announced by the Trustees of the IFRS Foundation in March 2021, is likely to accelerate convergence in global sustainability reporting standards with a focus on enterprise value and financial materiality. Many participants of the Progress Group, however, fear that reaching a consensus amongst these players may still take some time. Carole Crozat of BlackRock, Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson of PGIM Fixed Income, and Hortense Bioy of Morningstar are all in favor of corporate reporting standardization. Similarly, Florian Berg of MIT is in support of minimum reporting requirements for companies, which would provide companies with the flexibility of reporting on sector-specific issues while also minimizing the burden on disclosure efforts. In this respect, Florian Berg suggests that the industry-specific approach taken by SASB may be less onerous and predicts it may gain popularity.

C. Allocating (Internal) Resources

Publicly-listed companies are being inundated with information and data validation requests from various players to measure their ESG performance. How companies organize data collection and reporting efforts internally is therefore increasingly important to meet the increasing demand for progressive ESG practices and associated disclosures. Xavier Houot of Schneider Electric and Tjeerd Krumpelman of ABN AMRO Bank both report to have more than 10 employees responding to queries related to ESG ratings providers as well as contributing to the publication of sustainability reporting.

Schneider Electric and ABN AMRO Bank are both large companies that have weaved sustainability into their long-term corporate strategy; hence, their approach and allocated resources naturally supports such a vision.

However, not all companies will be able to dedicate this level of resource to monitor ESG trends and enhance their disclosures, which has led some to question if smaller companies are unfairly treated by ESG ratings providers. Research shows that larger companies tend to have better ESG practices and disclosures and therefore have better ESG ratings, and this could often lead to “ESG ratings inequality”.

As ESG ratings providers keep expanding their coverage universe to include small/ mid-cap companies and enter into emerging markets, such “ESG ratings inequality” is feared to widen. Hortense Bioy, Head of Sustainability Research at Morningstar (which acquired Sustainalytics in 2020), indicates Sustainalytics employs a slightly different rating framework for large and smaller companies to take into account the different quality of reporting. Such approach may help balance the disadvantage faced by smaller companies with limited resources that can be dedicated to corporate disclosure and the adoption of progressive ESG practices. This is also the approach used by most investors pursuing an “active” strategy, admitting one cannot evaluate companies of very different sizes in the same manner.

Irrespective of the company’s size, streamlining the sustainability reporting efforts across the organization is the first step a company can take, and this can be managed by a centralized team responsible for organizing the collected data and determining what, and how, relevant information gets reported. The internal team should either work alongside with or be part of the Investor Relations department to ensure that the company’s sustainability messaging is consistent across all communication channels and prioritize reporting on information that are most material to its shareholders and other stakeholders.

The second step for companies would be to map out the ESG issues that its investor base is focusing on by identifying the initiatives supported by investors and reviewing investors’ ESG policies, engagement priorities, and position papers. In an ideal world, companies will have sufficient internal resources to cater to all demands regarding ESG practices and disclosures; as resources are limited however, focusing on ESG issues that are relevant to the largest section of a company’s investor base will help ensure that companies get the most return on their investment in resources and time.

Similarly, companies should prioritize their focus on ESG ratings and data providers that are used by their top shareholders and for determining the constituents of main ESG indices. Focusing on the three to four main ESG ratings and data providers will enable companies to create a matrix for determining the most prevalent material ESG factors subject to evaluation. This matrix, together with investors’ preferences, should allow companies to get a good understanding of what are the main ESG practices and disclosures sought by the market and prioritize efforts accordingly.

D. Using All Forms of Engagement

As companies’ disclosure on their efforts and progress on sustainability is collected and reviewed not only by ESG rating agencies, but also by investors and proxy advisors among other stakeholders, companies should leverage their sustainability reporting as a key pillar of their engagement program with the market. Setting up a dedicated sustainability section on a company’s website that publishes regular updates to its ESG data and policies can be beneficial to allow third parties and investors to access the most recent practices and disclosures, especially considering that the reporting cycle of these rating providers tend to differ.

Apart from corporate disclosures, companies should directly reach out to the end users of the ESG ratings and data, i.e. investors. There are various ways in which companies can showcase their sustainability efforts and communicate their progress to investors, including by conducting ESG roadshows and/or ESG webinars and participating in investor conferences focused on ESG. Through direct engagement, a company has the opportunity to explain their sustainability strategy in detail and address any concerns its shareholders may have on ESG topics. As pointed out by Eugenia Unanyants-Jackson of PGIM Fixed Income, direct engagement allows investors to have a better understanding of companies’ ESG strategy, risk management and governance when the information in corporate disclosures and third-party ESG ratings may be insufficient.

IV. Concluding Remarks

As the incorporation of ESG factors into investment decision-making moves into the mainstream, and there being a legal requirement of investors to report on ESG data according to the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), investors’ reliance on ESG ratings and data providers will likely continue to increase.

Although concerns over green- and/or social-washing remain, investors are becoming increasingly well-versed on ESG issues and developing different ESG investment strategies. Hortense Bioy of Morningstar highlights, for example, that some investors implement a “contrarian” or “momentum” approach to ESG investing, through which they target companies with low or average ESG ratings and engage with them to improve their ESG performance and generate alpha.

The fact that ESG data and ratings is increasingly integrated into investment decisions, including credit ratings, leaves companies with little choice but to improve their ESG practices and reporting. Given the number of players in the ESG ratings and data market, engagement with these ESG rating and data agencies should be prioritized by considering the impact an ESG data and ratings provider has on the company’s investor base. Active engagement with the most relevant ESG ratings providers will enable companies to identify the improvements needed for obtaining higher ESG ratings and how to best achieve them, i.e. whether through improved practices or more comprehensive disclosures.

Recommendations

Organization

- Establish a cross-functional team to coordinate your company’s ESG practices and disclosures. A member of the investor relations department should be part of this team to ensure alignment with investors’ expectations.

- This team should lead your company’s efforts to draft annual sustainability reports and other periodic publications as well as provide survey responses to third-party ESG ratings and data providers.

- Ensure that the work and efforts of the internal sustainability task force are regularly reported to the executive team and monitored by the board.

- Prioritize which ESG ratings and data providers to monitor based on their use by your investor base, their influence on the composition of the main ESG indices, media exposure, and reputational impact.

Strategy

- Apply a double materiality approach when conducting an annual materiality analysis, by assessing your company’s impact on multiple stakeholders and potential impacts of ESG issues on the company’s business operations and financial performance.

- Research and map out which ESG topics are considered material for your industry by major ESG ratings and data providers and by other stakeholders, e.g. SASB. Compare the findings with your company’s internal materiality assessment.

- To ensure alignment with investors’ expectations, ask the investor relations team to list the ESG topics most critical for your company’s investors based on their one-on-one engagements and/or the investors’ public positions on ESG topics.

- Utilize third-party ESG ratings to conduct peer benchmarking and to identify strengths and weaknesses in your current ESG practices and disclosures. Most ESG ratings and data providers offer a complementary rating report to rated companies, though more granular information may only be available with a fee.

Disclosure

- Check if your company’s sustainability or integrated report is aligned to the sustainability reporting standards and ESG frameworks that are supported by your top shareholders.

- I nclude a content index at the end of your sustainability or integrated report linking disclosures to the reporting standards and framework used, such as the GRI, SASB, and TCFD.

- Continue to monitor trends in sustainability reporting standardization to anticipate the direction of travel and participate in consultations and pilot groups at the public policy level and industry association level.

- Avoid using complicated graphics and keep your sustainability-related disclosure and language simple so that relevant information can be captured by AIenhanced technology, such as natural language processing.

- Create a dedicated section on your website that houses your most recent ESG practices and disclosures to ensure that third parties and investors have access to the latest information when conducting their assessments.

- Communicate improvements in your ESG ratings and external recognitions, including high ESG scores or inclusion in ESG or sustainability indices, on your company’s website.

Engagement

- Establish a relationship with the main ESG ratings and data providers to find out their rating cycles and the timing of your company’s assessment. This will allow you to plan when you may need to respond to a questionnaire or provide feedback to their draft report/data.

- Embark on annual ESG roadshows to communicate your ESG Story. Such exercises will allow your company to communicate your approach to ESG, which may sometimes be missed in your corporate disclosures, as well as gain valuable insight as to what your investors deem as important when it comes to ESG.

- Leverage technology, such as social media and webinars, to increase your reach to all stakeholders when it comes to your ESG practices and disclosures.

Appendix

| Investor | Fund Name | Ratings Provider | Fund Geographic Focus | AUM USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BlackRock | iShares ESG Aware MSCI USA ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 13,393,909,210 |

| BlackRock | iShares ESG Aware MSCI EM ETF | MSCI | Global Emerging Markets | $ 6,133,269,946 |

| BlackRock | iShares Global Clean Energy UCITS ETF | Trucost | Global | $ 5,364,020,979 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI USA SRI UCITS ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 4,906,783,077 |

| BlackRock | iShares Global Clean Energy ETF | Trucost | Global | $ 4,688,270,456 |

| BlackRock | iShares ESG Aware MSCI EAFE ETF | MSCI | Global Ex USA | $ 3,986,046,628 |

| Invesco | Invesco Solar ETF | MAC Solar Index | Global | $ 3,631,536,720 |

| Vanguard | Vanguard ESG US Stock ETF | FTSE Russell / Sustainalytics | USA | $ 2,981,153,799 |

| UBS AM | UBS ETF MSCI World Socially Responsible UCITS ETF | MSCI | Global | $ 2,922,424,600 |

| DWS Investments | DWS MSCI USA ESG

Leaders Equity ETF |

MSCI | USA | $ 2,850,913,450 |

| BlackRock | iShares ESG MSCI USA Leaders ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 2,813,042,296 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI KLD 400 Social ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 2,628,079,729 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI World SRI UCITS ETF | MSCI | Global | $ 2,529,489,921 |

| BlackRock | iShares € Corp Bond ESG UCITS ETF | MSCI | Global | $ 2,313,295,450 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI USA ESG Select ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 2,298,359,723 |

| Invesco | Invesco WilderHill Clean Energy ETF | Wilder Shares | USA | $ 2,174,808,364 |

| First Trust Advisors | First Trust NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy Idx Fd | Clean Edge | USA | $ 1,999,312,383 |

| Amundi AM | Amundi Index MSCI USA SRI | MSCI | USA | $ 1,776,127,499 |

| UBS AM | UBS ETF MSCI USA Socially Responsible UCITS ETF | MSCI | USA | $ 1,694,870,381 |

| Amundi AM | Amundi MSCI Europe SRI | MSCI | Europe | $ 1,687,787,014 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI EM SRI UCITS ETF | MSCI | Global Emerging Markets | $ 1,649,846,241 |

| Amundi AM | Amundi Index Euro AGG Corporate SRI | MSCI | EuroZone | $ 1,637,856,820 |

| DWS Investments | DWS MSCI USA Low Carbo SRI Leaders UCITS ETF Fund | MSCI | USA | $ 1,605,626,300 |

| Vanguard | Vanguard ESG International Stock ETF | FTSE Russell / Sustainalytics | Global Ex USA | $ 1,584,406,842 |

| BlackRock | iShares MSCI EMU ESG Screened UCITS ETF | MSCI | EuroZone | $ 1,498,153,441 |

| DWS Investments | Xtrackers MSCI Japan Low Carbon SRI Leaders UCITS ETF Fund | MSCI | Japan | $ 1,376,637,600 |

| Legal & General IM | L&G US Equity (Responsible Exclusions) UCITS ETF Fund | Foxberry | USA | $ 1,354,956,961 |

| Invesco | Invesco Water Resources ETF | Sustainable Business LLC | USA | $ 1,314,086,715 |

| DWS Investments | Xtrackers MSCI World Low Carbon SRI Leaders UCITS ETF Fund | MSCI | Global | $ 1,279,214,700 |

| Lyxor AM | Lyxor MSCI Europe ESG Leaders (DR) UCITS ETF | MSCI | Europe | $ 1,250,947,837 |

| BlackRock | iShares € Corp Bond 0-3yr ESG UCITS ETF | MSCI | Global | $ 1,225,703,904 |

| DWS Investments | DWS ESG EUR Corporate Bond UCITS ETF(DR) | MSCI | EuroZone | $ 1,225,188,610 |

| UBS AM | UBS ETF – MSCI EMU Socially Responsible UCITS ETF | MSCI | EuroZone | $ 1,217,654,749 |

| Credit Suisse AM | CSIF (IE) MSCI USA ESG

Leaders BlueUCITS ETF Fund |

MSCI | USA | $ 1,205,691,791 |

| Amundi AM | Amundi Index MSCI World SRI | MSCI | Global | $ 1,157,458,108 |

| BlackRock | iShares J.P. Morgan ESG $ EM Bond UCITS ETF | Sustainalytics/ RepRisk | Global Emerging Markets | $ 1,125,351,354 |

| UBS AM | UBS Bloomberg Barclays MSCI Euro Liq. Corp. Sust.

UCITS ETF |

MSCI | EuroZone | $ 1,051,751,384 |

| BNP Paribas AM | BNP Paribas Easy Low Carbon 100 Europe PAB | Vigeo Eiris / CDP / Carbone 4 | Europe | $ 1,029,485,878 |

| Lyxor AM | Lyxor New Energy (DR) UCITS ETF | RobecoSAM | Global | $ 1,025,850,615 |

| DWS Investments | DWS MSCI Emerging Markets ESG UCITS ETF Fund | MSCI | Global Emerging Markets | $ 1,024,616,200 |

Source: SquareWell, Refinitiv/Lipper and MSCI ESG Research LLC as of Dec. 31, 2020

Print

Print