Thomas Singer is a Principal Researcher in the ESG Center at The Conference Board, Inc. This post is based on his Conference Board memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) and Will Corporations Deliver Value to All Stakeholders?, both by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

Companies traditionally communicate their sustainability activities to stakeholders through large, comprehensive reports, often running more than 100 pages, that go by a number of different names: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG), or Sustainability. Almost all S&P 500 companies issue these reports, indicating that sustainability storytelling is now mainstream and expected of large US companies. In addition, companies increasingly customize information on their sustainability initiatives for rating agencies, business partners, regulators, and others.

Companies face a number of challenges in telling their sustainability stories: 1) deciding what issues are truly important to disclose to convey a clear, cohesive, authentic, and distinctive story about the company; 2) maintaining consistency, ensuring that their story effectively addresses the interests of multiple stakeholders; 3) providing information that’s not only accurate and reliable, but genuinely trusted (including during crises); and 4) managing the ever-evolving—and often frustrating—landscape of sustainability regulations, reporting frameworks, and ESG rating firms—as well as the growing demands by business partners who have their own requests for sustainability-related information.

To tackle some of these challenges, The Conference Board convened a working group of over 300 executives from more than 150 companies who met over the span of 10 months to focus on how companies can tell their sustainability stories authentically, reliably, and effectively to multiple constituencies. [1] Some members of this working group also responded to surveys. This post captures the key insights from the working group sessions as well as the survey results. More detailed guidance can be found in the four accompanying practical guides.

Insights for What’s Ahead

Practical Guide 1: Determining what to include in your sustainability story

- Lengthy CSR/Sustainability/ESG reports are becoming a thing of the past. Producing an annual or biennial comprehensive report can be useful for a company that’s new to sustainability reporting or wants a single reference document (although even then it’s outdated as soon as it’s produced). But companies and stakeholders alike are finding that these phone book–style reports don’t meet their needs. Instead, companies are looking to focus on the handful of issues that truly matter to their long-term future and have the greatest impact on stakeholders, society, and the environment. In our polling of some working group members, most companies identify up to 20 issues as significant. Of these, a handful of issues “truly move the needle.” Focus is especially needed when a company is trying to inspire employees, motivate customers, and strengthen its brand with the general public. At the same time, investors, reporting frameworks, and ESG rating firms are looking not just for a narrative that describes the company’s main focus areas, but also for timely data on a range of topics—these data often don’t fit neatly into a narrative report and need to be provided as soon as they are available and verified.

- Reach agreement on whether you will use materiality as a standard for your disclosures and what you mean by “material.” While companies and stakeholders emphasize the need to focus on “material” information, they often mean different things. A threshold question is whether to use the term “material” at all. A survey of some working group members found that many companies don’t use the term “material,” and only a small minority use the traditional SEC definition of materiality—which focuses on investors’ views of the financial performance of the company—in determining what to report. [2] While the line between “financial materiality” and “sustainability materiality” may evolve over time as investors increasingly view sustainability-related areas as key to their decisions, using the term “materiality” as the disclosure standard at this point can lead to confusion, especially as the legal definition of materiality or standard for disclosure can vary by jurisdiction around the world. Whatever the term, agree upon the standard you’re using and be explicit about that in your disclosures.

- Take a fresh look at your analysis and process for determining what issues meet your disclosure standard. While most companies rely on the X/Y axis framework (which often prioritizes issues based on their importance to the business vs. importance to stakeholders), the framework has limitations: issues of importance to the “company” and to “stakeholders” are likely to converge over time, and the X/Y framework focuses on importance to stakeholders without explicitly assessing impact on stakeholders, society, and the environment. You may therefore want to use a variety of frameworks, including the framework and “heat map” traditionally used in risk management. External reporting frameworks (e.g., Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, Task Force on Climate-Related Disclosures) can be useful guides for determining or confirming material issues, but avoid using these frameworks as your primary input. Instead, take a company-first approach to determining material issues.

- Regardless of the disclosure standard and analytical framework you use, stakeholder input is vital. While your company will inevitably need to determine how much weight to give different stakeholders’ views, seek broad input, including from stakeholders outside the US. Consider not just what’s important today, but what’s likely to be important in the future. Companies are dynamic enterprises, stakeholder expectations are constantly evolving, and the process for determining what to include in your sustainability story should be equally dynamic and forward looking.

Practical Guide 2: Telling your sustainability story authentically and effectively

- Align your sustainability story with your company’s business strategy. To ensure authenticity, your sustainability story should be anchored in your company’s business strategy, ambition, and culture—linking to business strategy is the biggest challenge for companies, the working group found. To do so, ensure your sustainability story matches how the company makes business decisions, runs its operations, and approaches risk management and product development/innovation. Sustainability efforts should be viewed not as ancillary but as fundamental to furthering the company’s mission.

- Engage your employees. Employees are key stakeholders who can identify the issues that truly matter to your company. But they can do more than that. They can offer a “reality check” for keeping your story authentic; as they will ultimately be responsible for carrying out much of your sustainability story in their countless actions and behaviors, they can be powerful ambassadors—especially if your story passes their gut check. Employees can also be a source of the language, stories, and images in your sustainability reporting. The specific ways in which you engage employees can vary; you might focus on all employees or a subset of them.

- Tell your story through a tiered approach, including a main narrative focused on the highest priorities and supplemental data-heavy communications focused on specific areas of stakeholder interest. The main narrative should incorporate supporting data that focus on the few highest-priority issues that can be adapted to different audiences. You can also tell your company’s story for the next tier of issues in stand-alone documents or in a searchable database; these offer narrative context but are data heavy and provide a deeper dive on specific topics (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions; worker health and safety; diversity, equity & inclusion; supply chain resilience).

- Perhaps the biggest challenge facing companies is accommodating business partners. Every firm is pursuing its own sustainability story, so businesses expect their suppliers and partners to help them meet their own goals. This can be positive, as sustainability can be a competitive advantage. But it can also be chaotic. The key right now is dialogue with your business partners to set reasonable expectations. Sometimes this can be done industry-wide, but often firms within an industry don’t agree on either the key sustainability issues or the ways to address them. So one-on-one dialogue with business partners is going to be necessary.

Practical Guide 3: Stakeholder engagement and telling your sustainability story reliably

- Embrace balance in your disclosures. Most companies resist including negative information in their disclosures. But legal risks are associated with both disclosing negative information and failing to disclose such information or overstating the positive aspects of your story. Beyond legal concerns, neglecting or downplaying negative sustainability information risks your credibility with stakeholders and may make you susceptible to investor accusations of greenwashing. [3] Your reporting should be balanced and transparent. It’s generally better for the company to put negative information in context than to leave it to others to build their own narrative based on it.

- Maintain a dialogue and transparency during a sustainability-related crisis. There’s ample room for improving dialogue with key stakeholders, input from the working group suggests: almost half of survey respondents note they are dissatisfied with their company’s dialogue with consumers, and 41 percent are dissatisfied with their company’s dialogue with employees. Know who’s responsible during sustainability-related crises, be transparent with your employees, and rely on your community relationships. Doing so can help your company build trust and prepare for the long haul, since these crises can last a long time.

- Consider ramping up the use of external sustainability assurance services to ensure the reliability of your reporting. Nearly 3 out of 4 respondents to our surveys plan to obtain assurance or expand the scope of what they currently assure. External assurance gives investors (as well as business partners and regulators) confidence in the accuracy of your data, and it can improve your external ratings. But it can also strengthen your internal controls and reporting systems, and drive better decision-making based on higher-quality sustainability information. But this process can be expensive and time consuming, so you may wish to increase the use of assurance services over time.

Practical Guide 4: Dealing with regulations, reporting frameworks, and rating agencies

- Prepare for increased and multitiered regulation of ESG disclosure. Policymakers are focusing on all layers—companies, investors, and intermediaries. Unlike during prior waves of governance regulations, issuers and investors are likely to have a great deal in common: both will be subject to regulation, and both will be seeking information to help businesses and investors make informed decisions, which requires a degree of both consistency and flexibility. Indeed, the fact that 79 percent of working group participants surveyed believe regulation will be at least somewhat beneficial signals an openness to regulation, especially if it combines some mandatory elements with substantial flexibility for companies to tell their own story. Build coalitions with investors and other stakeholders, as you’ll likely find you have common goals. Future regulation is inevitable, but it can also be, on balance, beneficial.

- The reporting frameworks may be consolidating, but don’t expect much change in the near term. At best, these frameworks are reference points. [4] Focus less on the frameworks and more on reporting the most relevant issues. But have a plan for commenting on why you aren’t reporting on certain metrics.

- Don’t go chasing after all the ESG rating firms. ESG rating firms are proliferating, so be strategic about which rating organizations you engage with and how. The biggest problem companies have with ESG rating firms is the time and resources required to respond to information requests. Focus on a few, comply with a few others, and don’t worry about the rest. This approach requires an internal process and fortitude. Consider industry-based discussions with investors to reduce your reliance on intermediaries.

Defining sustainability remains a challenge for companies

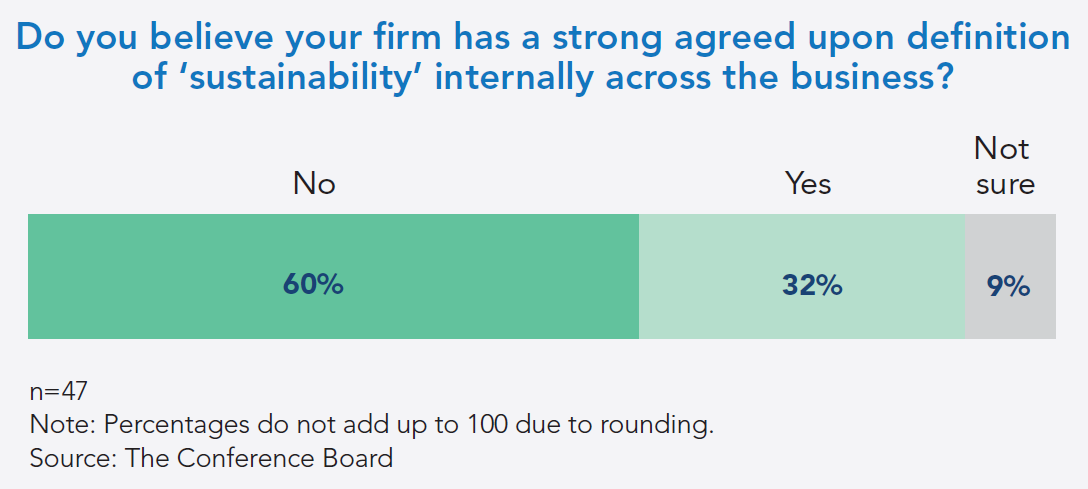

Despite the prevalence of sustainability reporting, many companies still don’t have internal clarity on the meaning of “sustainability.” In a poll of some working group participants, 32 percent say their companies have a strong agreed-upon definition of sustainability internally across the business.

Part of the challenge has to do with people’s associations with the term “sustainability.” For example, some working group members note that the term is often primarily associated with environmental issues:

“Given the recent social concerns around diversity and inclusion driven by the racial injustices, our board is asking us to broaden the description. Sustainability primarily reminds people of environmental issues.”

“Occasionally we find that people confuse sustainability with only the environmental or ‘green’ efforts.”

The terminology your company uses plays a key role in your ability to communicate effectively to different audiences. For example, the term “ESG” might resonate with the board and investors, whereas “sustainability” might resonate better with customers and other stakeholders. “Sustainability” also aligns with some of the leading reporting frameworks and guidelines, such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, and Global Reporting Initiative. When choosing terminology, consider which rallying cry will be most effective for motivating employees.

While there’s no universally accepted definition of “corporate sustainability,” many of the most prominent definitions share common elements: integrating into business strategy and operations; including financial, economic, social, and environmental factors; addressing multiple stakeholders; assessing risks and opportunities; and promoting long-term value. The working group adopted the following definition of sustainability, which incorporates key elements of existing definitions:

“Sustainability” encompasses the full range of initiatives designed to promote the long-term welfare of a company, its multiple stakeholders, society at large, and the environment. [5]

Against that backdrop, “ESG” can be seen as the set of categories of nonfinancial measures and metrics used to achieve sustainability.

Endnotes

1A working group offers members of The Conference Board a venue where they can actively engage on a key topic. It provides members an opportunity for peer-to-peer dialogue to address shared challenges, and gives members access to experts, the latest research, benchmarking data, and examples of best practices. The working group “Telling Your Sustainability Story,” jointly organized by The Conference Board ESG Center and Marketing & Communications Center, met five times between July 2020 and May 2021.(go back)

2TSC Industries, v. Northway, Inc., 426 U.S. 438, 449, 1977. (“[A]n omitted fact is material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important in deciding how to vote… Put another way, there must be a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.”)(go back)

3The following podcast includes more details on how investors spot signs of greenwashing: “Impact Investing and its Impact on You,” ESG News & Views, The Conference Board, May 11, 2021.(go back)

4See: Minji Xie and Anke Schrader, “The Evolving Landscape of Sustainability Reporting Frameworks,” working title, The Conference Board, forthcoming 2021.(go back)

5This is also the definition of corporate sustainability used in recent reports by The Conference Board, including: Thomas Singer, “Five Ways a Sustainability Strategy Provides Clarity in a Time of Crisis,” The Conference Board, April 2020.(go back)

Print

Print