Cynthia A. Williams is the Osler Chair in Business Law at Osgoode Hall Law School at York University; Sarah Barker is a Partner and Head of Climate Risk Governance at MinterEllison; and Alex Cooper is a lawyer at the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI). This post is based on a memorandum by Prof. Williams, Ms. Barker, Mr. Cooper; Robert G. Eccles, Visiting Professor of Management Practice at Oxford University Said Business School; and Ellie Mulholland, Director of the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) and Will Corporations Deliver Value to All Stakeholders?, both by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; For Whom Corporate Leaders Bargain by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy—A Reply to Professor Rock by Leo E. Strine, Jr. (discussed on the Forum here).

As exemplified by the attention paid by the business and investor communities to the COP26 event, the last few years have seen a significant change in the understanding of climate change as a material risk to businesses, with government and capital markets responding. There has also been a notable increase in the number of so-called ‘Caremark’ claims against directors and officers for failing to exercise proper oversight surviving motions to dismiss. These two developments, construed together, indicate that directors and officers of Delaware corporations are navigating their corporations through an increasingly risky environment, and there is the potential that they may face litigation and ultimately personal liability for failing to manage these risks. Delaware directors and their attorneys must understand this new legal risk.

Climate change poses physical, economic transition and liability risks to corporations and their business models, which are already becoming apparent in the US. Wildfires and extreme storm events, the likelihood and intensity of which have been increased by climate change, have led to billions of dollars of losses. The Biden administration has emphasized climate change as part of US foreign and domestic policy as well as financial regulation, and has set a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50-52% by 2030, as part of a transition to net zero greenhouse gas emissions, relative to 2005 levels, by 2050, and has released a long-term strategy detailing how the US can achieve this goal. An increasing number of countries worldwide have set out policies to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century, and financial institutions and investors are increasingly asking their investee companies to demonstrate how their business models are compatible with the transition to a low-carbon economy. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has indicated that it will enforce its existing guidance on the disclosure of climate change risk, and is widely expected to promulgate climate change and ESG disclosure requirements, while the Financial Accounting Standards Board has issued guidance to staff on the incorporation of ESG matters, including climate change, into financial statements. The Federal Reserve Bank Board of Governors has recognized climate change as posing a systemic risk to the US financial system. Climate litigation is becoming increasingly common and varied, and boards should be increasingly alert to the risk that their companies could find themselves the subject of strategic litigation or traditional compensation claims when climate losses arise.

As discussed in detail in a new paper published in October 2021 by the Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI), climate change has therefore evolved from an “ethical, environmental” issue to one that presents foreseeable financial and systemic risks (and opportunities) over mainstream investment horizons. This evolution has substantially changed the relevance of climate change to the governance of corporations, which has implications for the fiduciary duties of directors and officers under Delaware law.

Delaware law imposes two primary fiduciary duties on directors and officers: a duty of loyalty and a duty of care. The duty of loyalty requires officers and directors to act in the good faith belief that their actions are in the best interest of the corporation, to put the interests of the corporation first, and to provide oversight of legal compliance and, in principle, mission-critical operations (the ‘duty of oversight’). An alleged breach of the duty of loyalty (including the duty of oversight) is not protected by the business judgment rule, cannot be exculpated by corporate bylaw provisions, and cannot be indemnified through corporate policy.

The duty of oversight requires directors and officers to implement information and reporting systems that are reasonably designed to provide accurate information sufficient to allow management and the board to reach informed judgments concerning the corporation’s “operational viability, legal compliance and financial performance.” Directors and officers may be found liable for a breach of their duty of loyalty where they have failed to try to establish such systems or where, having implemented such systems, they fail to monitor them. Claims alleging breaches of fiduciary duty in this manner are known as ‘Caremark’ claims, following the landmark decision in this vein. While Caremark claims are difficult to bring and have historically tended to be dismissed in their early stages, a series of recent Caremark cases, following the 2019 Delaware Supreme Court decision in Marchand v Barnhill, have survived motions to dismiss. [1] These more recent cases suggest that boards should be more sensitive to ‘red flags’ on compliance in mission-critical operations – particularly in monoline companies. This series of cases may indicate greater potential exposure to Caremark liability. Directors and officers should therefore ensure that they have adequate oversight of regulatory compliance, and – potentially – mission-critical operations. Although no cases regarding purely operational oversight have been successfully brought under Delaware law, they are possible, and have been allowed to proceed in other States).

Climate change is likely to significantly increase the risks facing a corporation’s operations, and through government’s efforts to halt climate change and protect economies and communities from its impacts, increase its regulatory obligations. Therefore, in the context of climate-related risks, oversight liability may arise where directors and officers:

- fail to consider or oversee the implementation of climate-related legal risk controls;

- fail to monitor mission-critical regulatory compliance, either specific climate change-related regulations or existing regulations which require consideration or disclosure of climate change risks. This latter category is likely to include a broad range of regulations, but may include: securities laws, which require listed companies to disclose material risks; environmental laws, as the physical effects of climate change catalyze infrastructure failure; and health and safety laws for companies with employees are exposed to increasingly hostile conditions; or

- fail to monitor climate-related mission-critical operational and business risks.

Directors and officers should be particularly alert to the potential overlap between ‘legal compliance’ and ‘business risks’ where the alleged failure relates to a material risk to the corporation’s financial position or prospects. This is because an indication of a failure in the system of monitoring such risks would necessarily indicate that the corporation is at risk of non-compliance with its disclosure obligations under securities laws, at least for companies with public reporting obligations.

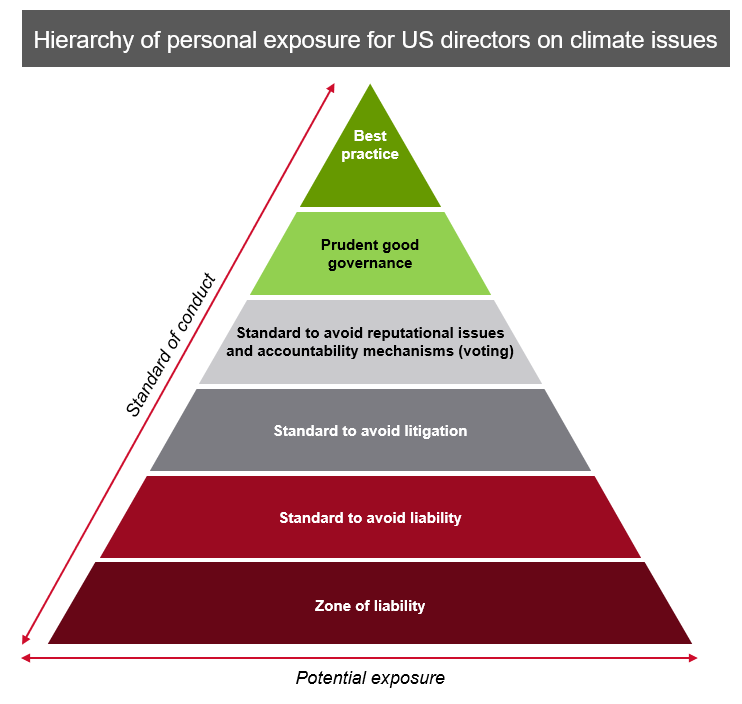

While directors and officers are likely to be particularly focused on the risk that they may be found personally liable for a breach of their duties, proper compliance with fiduciary obligations requires acting to a higher standard. Given the defenses available to fiduciaries, and the difficulty in bringing claims for breach of fiduciary duty, a director or officer found to be liable for such a breach will generally have acted egregiously. The standard to which directors and officers must act to avoid liability is therefore a bare minimum. To minimize the risk of such claims being brought, directors and officers will need to act to a higher standard to avoid the attentions of litigious shareholders; and to further reduce their potential exposure, and to ensure proper compliance with their legal obligations, directors and officers should seek to follow best practices.

In particular, directors should be cognizant of reputational risks associated with derivative actions. Shareholders seeking to bring a Caremark claim commonly seek the inspection of corporate books and records in advance of filing. The Delaware Supreme Court has affirmed that a shareholder only needs to present a credible basis that there has been a wrongdoing in order to do undertake such a search, and has also allowed shareholders to access emails and other communications between directors. Given the public nature of litigation, such searches can have reputational implications.

This ‘sliding scale’ of the standards to which directors and officers should adhere, and the corresponding risks, are set out in the diagram below.

Climate change significantly increases the risks a corporation faces, and therefore may catalyze a breach of directors’ and officers’ duty of oversight. While it is rare for directors or officers to be found liable for breaches of this fiduciary duty, and such claims are difficult to bring and have significant defenses, the potential for an action for breach of duty is credible. The number of climate change-related cases globally, and in particular in the US, has increased significantly in recent years, and the capacity of determined litigants should not be underestimated.

The CCLI paper contains and full analysis and discussion of both climate change risks, and the risks of litigation faced by directors and officers. The paper also offers some high level guidance on inquiries boards may wish to make in order to ensure that they are fulfilling their duty to oversee climate change risks, and avoid the potential for finding themselves below the standard required to avoid liability.

Endnotes

1In re Clovis Oncology Inc. Derivative Litig., No. 2017-0222-JRS, 2019 WL 4850188; Hughes ex rel. Kandi Technologies Grp. v. Xiaoming Hu, No. 2019-0112-JTL, 2020 WL 1987029 (Del. Ch. Apr. 27, 2020); Teamsters Local 443 Health Servs. & Ins. Plan v Chou No. 2019-0816-SG, 2020 WL 5028065 (Del. Ch. Aug. 24, 2020); In re The Boeing Co. Derivative Litig. No. 2019-0907-MTZ, 2021 WL 4059931 (Del. Ch. Sept. 7, 2021).(go back)

Print

Print