Carlo M. Funk is the lead ESG Investment Strategist at State Street Global Advisors covering Europe, the Middle East and Africa regions (EMEA). This post is based on his SSgA memorandum.

Climate change has already become one of the most prominent line items on the world’s agenda. But we believe that its impact on the global macroeconomy is just beginning and increasing in pace. In our view, investors should think of the transition to a low-carbon economy as a multi-dimensional shock event, spread out over time, that will have major regulatory and economic consequences and profound investment implications. Investors who think the pace of climate-related change in markets/economies will be slow could be in for a major surprise.

A Stronger and Faster Transition

Recent events, country-specific incentives, and multiple positive feedback loops are setting the stage for faster movement toward decarbonization in 2022 and beyond.

First, COP26 highlighted the urgency of global action. Under the Paris Agreement in 2015, nearly every country agreed to work together to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, with an aim of 1.5 degrees. However, data shows that the targets that countries announced in Paris do not remotely reach that goal. COP26, which was seen as an opportunity for countries to make more aggressive targets, resulted in a wide range of outcomes. (For more of our thinking on the ramifications of COP26, see Post COP26: Outcomes and Opportunities.)

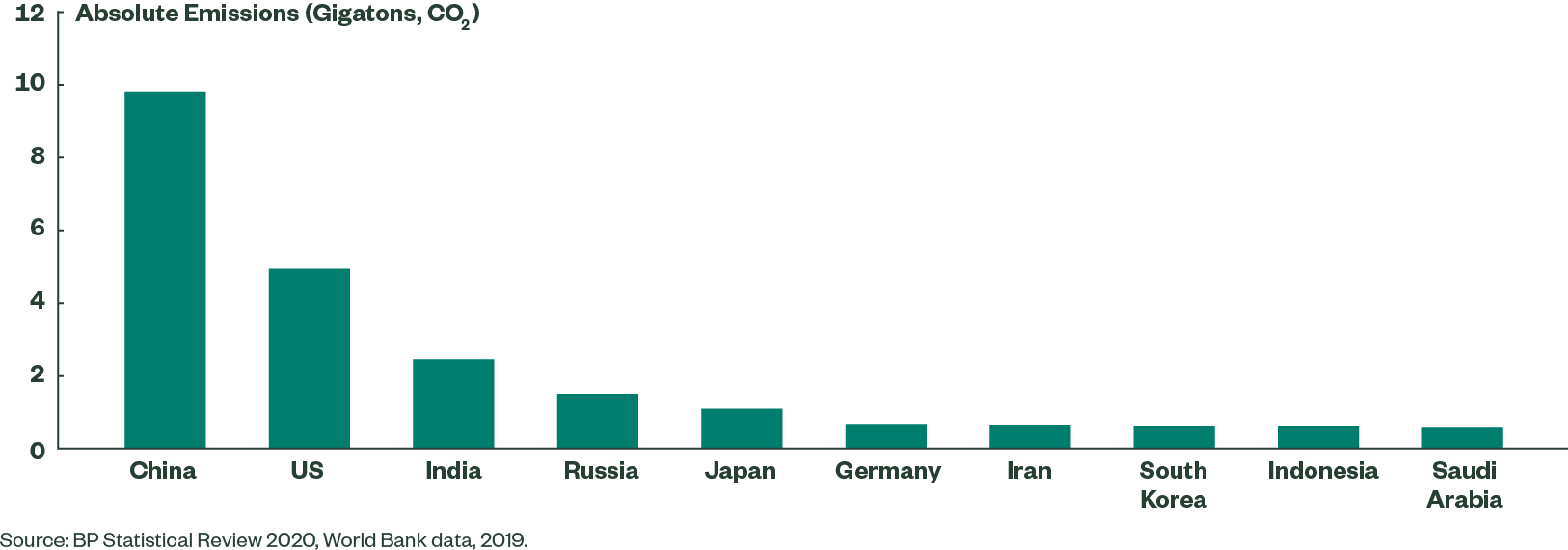

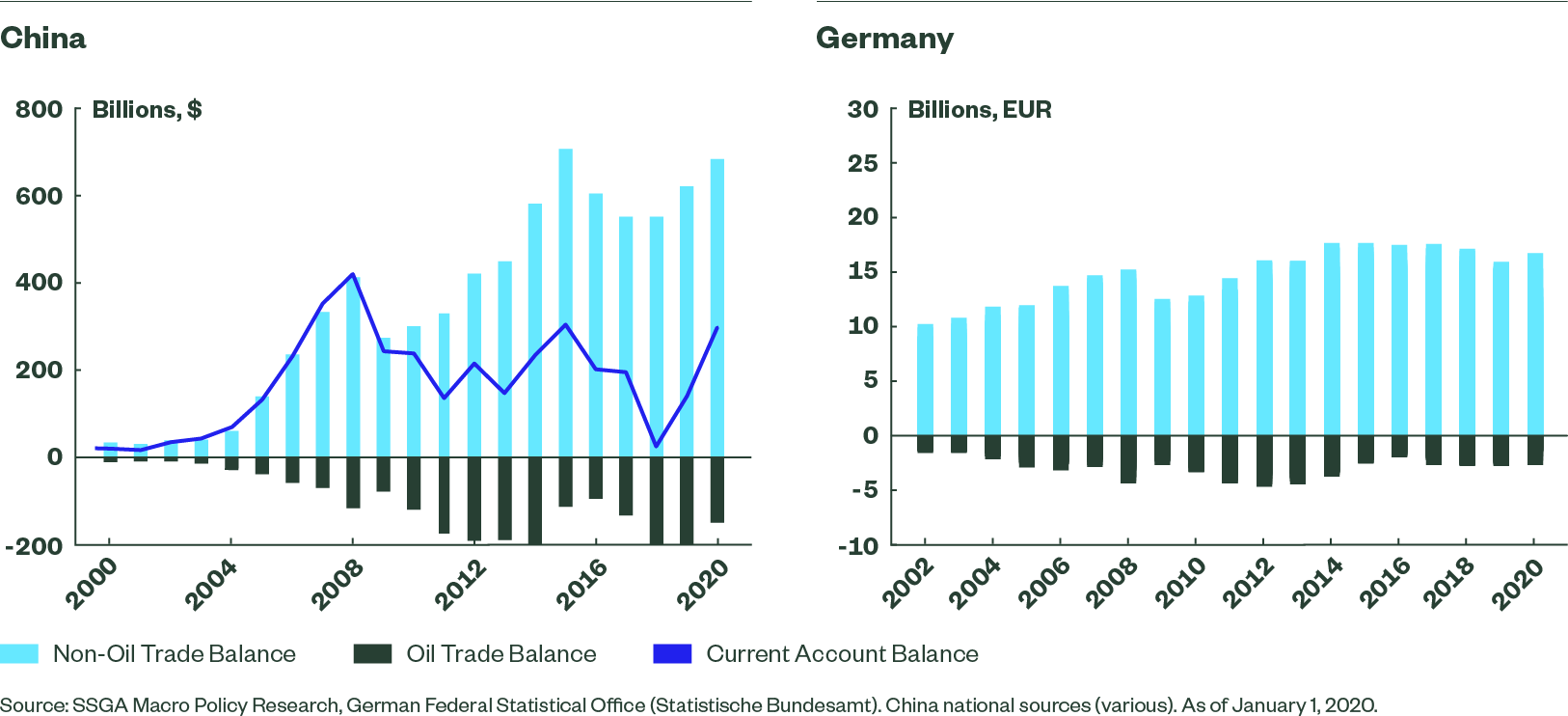

Second, we note that decarbonization has second-order effects that could drive heavier participation from developed and emerging markets. For example, geopolitical superpowers (the US, China, and Europe) are incentivized to stay on top of the race to become a climate leader because the transformation to a low-carbon economy will come with enormous opportunities (similar to other disruptive shifts, like digitalization). India is seeking to become a global power, but it is also the third-largest emitter behind China and the US (see Figure 1). India’s pledges made at COP26 are less aggressive than those of other countries, but the fact that India made a net-zero pledge is still a significant development. Also, most developed market economies are net energy importers under the current fossil fuel regime. Decarbonization could therefore improve the balance of trade for these nations (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: India Represents an Opportunity for Increased Decarbonization

Figure 2: Decarbonization Could Improve the Balance of Trade

Finally, positive feedback loops underpinned by innovation will likely lead to a mass displacement of fossil fuels by renewables—potentially much more quickly than many would anticipate. These loops include:

The volume-cost feedback loop. As renewable energy volumes rise, costs for businesses and consumers fall, which then spurs more volumes. On the flip side, falling fossil volumes mean lower utilization rates, which increase fossil fuel costs and drive down demand. Capital spending by the incumbent energy sector has already started to drift lower—even as crude oil prices have ticked higher—as oil and gas companies have reduced spending on petroleum.

The technology feedback loop. As more electric vehicles come on the road, battery costs decline, which then increases renewable penetration. By contrast, peaking fossil fuel demand means a collapse in the innovation of fossil fuel-based technologies.

The expectations feedback loop. As demand for renewable energy continues to grow, oil and gas incumbent earnings and operational forecasts will look less credible. As traditional energy companies’ models change, so too do the perceptions of investors and policymakers, driving price movement and revised expectations.

The finance feedback loop. As growth in renewable demand leads to more capital contribution from investors, the cost of capital for renewable energy companies falls, enabling even more expansion. In contrast, the greener economy will force fossil fuel companies to face higher costs of financing. Note, for example, that an annual $1 trillion in green bond issuance is expected by 2023, versus $228 billion in the first half of 2021, according to the Climate Bonds Initiative. [1]

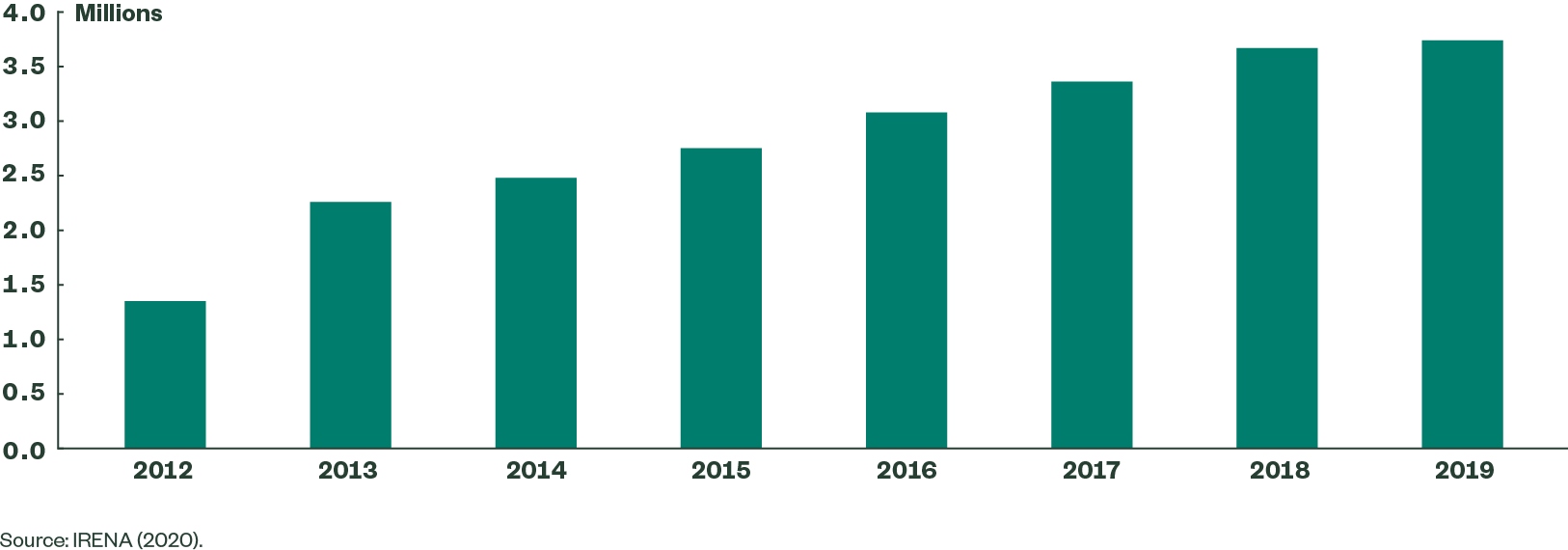

In addition, the broader society feedback loop, the politics feedback loop, and the geopolitics feedback loop will further accelerate this transformation. As society becomes more concerned with the climate crisis and comes to better understand the financial benefits of renewable technology, people will likely change their behavior. Politicians in turn will likely realize that renewables can generate more “gain” than “pain” (see Figure 3), and geopolitical superpowers may see similar opportunities, leading to a race of one-upmanship that accelerates the movement toward decarbonization. (For more details, see Spiralling Disruption: The Feedback Loops of the Energy Transition.)

Figure 3: Job Generation from Renewables Could Move Policy Agendas

(Solar Jobs, Millions)

Implications for Investors

While we have already seen long-term investment move away from the incumbent energy sector, we know that most diversified investors still have significant exposure to fossil fuels via various value chains, both in the equity and fixed income markets. To manage the climate transition, investors should consider the following:

The need to obtain clarity regarding their exposure to the fossil fuel sector and the associated risks. A massive economic depreciation exercise for carbon-heavy assets, alongside an appreciation exercise for carbon-neutral assets, is looming, and this situation will present risks as well as opportunities. Investors with a solid understanding of the regulatory and economic implications of the transition to a low-carbon economy can build more resilient portfolios and take advantage of these opportunities. Portfolio analysis using forward-looking climate metrics is a key element of this process, so finding the correct analytical tools regarding transition forecasts and physical risk models is crucial for investors.

The increasing importance of stewardship and engagement. It is well understood that divestment alone is not an adequate option for investors and can, at times, also curb the benefits of efforts to allocate capital sustainably (see Engage or Divest? The Question at the Heart of Climate Impact).

The consequences of regulatory change—better disclosure and new financial models with which to integrate changing ESG criteria. The IFRS Foundation announcement regarding the establishment of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is an important step in the quest for better ESG disclosure. The inclusion of carbon pricing into equities-market valuations still poses modelling challenges for investors, and pricing considerations will have implications on valuations and credit analysis.

The effect of decarbonization on corporate earnings. Government fiscal policies to help build sustainable economies could also lead to company balance sheet damage from tax increases, even if these tax hikes are shared with households. In addition, decarbonization is a structural inflation driver for economies, as the inputs and technologies for sustainable businesses are still in their infancy. This could hit carbon-intensive sectors particularly hard. On the positive side, investors could benefit from opportunities in green technology such as low-carbon steel and cement, carbon offset technologies, and biofuels (just to name a few). Investors could also benefit from the pairing of greening and digitization, with an expected acceleration in software and artificial intelligence (AI) related to climate change.

Closing Thoughts

Investors are facing a potentially parabolic rise in climate awareness in coming years, and positioning for this reality is prudent for portfolio management. The drivers of increasing interest in decarbonization include the outcomes of COP26 and many positive feedback loops that will push climate even more to the forefront. Investors will likely benefit from greater disclosure requirements, but they will also need to effectively integrate climate risks and opportunities into financial models and deeply understand their carbon exposure.

Encouragingly, results from our recent global ESG survey of 300 institutional investors showed that most investors plan to implement decarbonization targets over the next three years (i.e., 71% in Europe, 70% in Asia Pacific, and 61% in North America). Investors plan to use a wide range of asset classes to express their climate targets and, in a change from our prior survey, [2] they cite their responsibilities to drive the economic transition and to help to solve the global climate crisis as their top two reasons for pursuing climate investment strategies. These survey responses could imply that many market participants understand the expected acceleration in decarbonization, but they also show investor momentum—yet another potential driver of climate-related market movement. In sum, we believe that preparation for this shifting landscape is key.

Endnotes

1Jones, Liam. 2021 Green Forecast Updated to Half a Trillion—Latest H1 Figures Signal New Surge in Global Green, Social & Sustainability Investment. Climate Bonds Initiative, as of August 31, 2021.(go back)

2State Street Global Advisors, Into the Mainstream: ESG at the Tipping Point (November 2019).(go back)

Print

Print