Shagun Agarwal is a Climate Solutions Associate at ISS ESG. This post is based on his ISS memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita (discussed on the Forum here); Companies Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare Not Market Value by Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales (discussed on the Forum here); and Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee by Max M. Schanzenbach and Robert H. Sitkoff (discussed on the Forum here).

Climate litigation is an increasingly common and accessible area of environmental law, and is being used to hold countries and public corporations to account for their climate mitigation efforts and historical contributions to the problem of climate change.

A Global Surge in Litigation

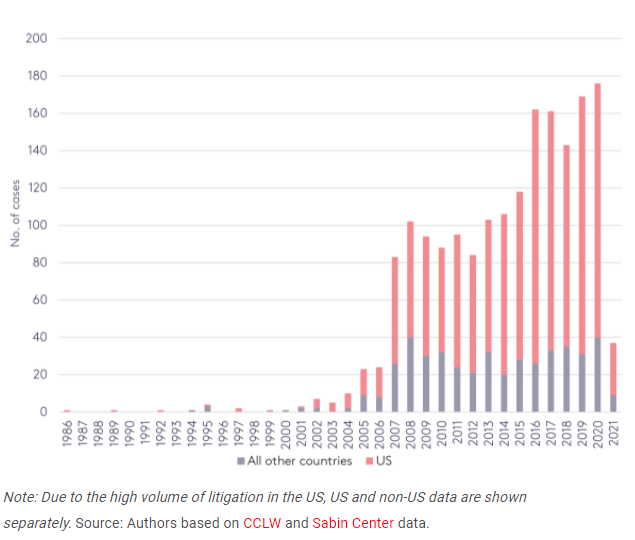

There is a clear upward trend in the use of climate litigation. Until 2017, the total number of climate litigation cases was 884 across a total of 24 countries, with 654 of these cases being in the United States. By 2020, this number had nearly doubled to 1,550 cases across 38 countries.

Figure 1. Climate Litigation, 1986-2021

Source: Global Trends in Climate Litigation, London School of Economics, 2021

Consequently, litigation risk is emerging as an expanding subset of both physical and transition risks. With the varying validity of the multitude of Net Zero claims being made, this risk becomes an even more important aspect to be considered.

The cases have so far broadly fallen into one or a combination of six major categories:

- Climate rights

- Domestic enforcement

- Keeping fossil fuels in the ground

- Corporate liability and responsibility

- Failure to adapt and the impacts of adaptation

- Climate disclosures and greenwashing

Figure 2. Climate Litigation Categories

Source: Global Climate Litigation Report, 2020

While each category has seen a wide spectrum of scrutiny, there has been a growing focus on climate disclosures and greenwashing. Because of growing awareness, accessibility, and disclosure requirements, countries and increasingly corporations find themselves being held to account for their climate mitigation pledges and consequent environmental impact, by investors and stakeholders alike.

Holding Corporations Accountable for Impacts on Climate Change

The current rate of increase in cases against private and financial sector actors indicates more diversity and complexity in the arguments that are being used, particularly those based on notions of fiduciary duty and greenwashing.

Examples of the growing standards of accountability that are now being legally levied include the following cases:

- The York County v. Rambo case (pending), where bond investors accused the Pacific Gas and Electric Company of failing to disclose the risk of its non-compliance with electrical line maintenance standards and consequent contribution to increasing wildfires in the region.

- Friends of the Earth et al. v. Prefect of Bouches-du-Rhône and Total where the Administrative Court of Marseille invalidated Total’s permit to operate a biorefinery and ordered a deeper study of the climate impacts of palm oil production.

- McVeigh v Retail Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd, where a member of a super fund known generally as ‘Rest’ claimed the fund was in breach of Australia’s Corporations Act 2001 due to failure to provide information on how Rest was managing climate change risks. Although resolved in an out-of-court settlement, the case has set a strong precedent for acknowledging the material risk climate change poses for institutional investors.

Similar rulings across other categories continue to set a stronger global precedent for individuals and organizations to utilize legal avenues in their efforts to drive action on climate change.

In a landmark 2021 case (Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell), a group of Dutch NGOs won a ruling against global energy company Royal Dutch Shell. The premise of the argument was rooted in the unwritten standard of care found in Section 162 of the Dutch Civil Code. After four days of hearings, the Court concluded that:

“The standard of care included the need for companies to take responsibility for Scope 3 emissions, especially where these emissions form the majority of a company’s CO2 emissions, as is the case for companies that produce and sell fossil fuels.”

As a result, Shell was ordered to reduce Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions across its entire energy portfolio by 45% relative to 2019 emission levels by 2030.

Investors’ Response to Climate Litigation

The impact of such hearings and their potential repercussions raise questions around what investors should be doing, and what comes next?

There are three key aspects which require consideration:

- The need to acknowledge climate litigation as an evolving and integral risk to investee corporation operations and investment growth.

- The incorporation of litigation risk into assessments of climate-related financial risks and the integration of litigation risk into investment growth modeling.

- Encouraging comprehensive disclosure to mitigate the legal risks as much as possible.

The growing occurrences of natural disasters, whether extreme flooding in Germany, sweltering heat waves in the US and Canadian Pacific Northwest, raging bushfires in Australia, or record typhoons and cyclones in Thailand, have become deeply emblematic of a world increasingly affected by climate change.

The global scope and varying intensity of climate change events not only poses a direct risk to investors’ physical assets, but it also underscores the consequent risk of and need for transitioning towards a low-carbon economy. Therefore, adding to these risks the risk of potential legal action emphasizes how climate litigation is not just an additional dimension to physical and transition risk, but a separate risk to be assessed.

Addressing these conditions and their interplay through more robust emissions data and diligent reporting is therefore imperative, not just for corporations and investors, but for asset owners and managers as well. As investors, corporations, and countries plan and progress in their respective Net Zero transitions, such legal battles are only going to multiply in the coming years.

Print

Print

One Comment

As a debater, this article is one of the most useful thing’s I’ve ever found. It completely non-uniques the litigation DA. Subodh Mishra, you are a savior and forever in my heart.