Duncan Paterson is Head of the ESG Thought Leadership Program at ISS ESG; and Katharina Gallowski is Associate Vice President for Research at ISS ESG. This post is based on their ISS memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Politics and Gender in the Executive Suite by Alma Cohen, Moshe Hazan, and David Weiss (discussed on the Forum here); and and Will Nasdaq’s Diversity Rules Harm Investors? by Jesse M. Fried (discussed on the Forum here).

The topic of gender diversity has been on the lips of the responsible investment sector for many years. One of the earliest factors that allowed investors to identify those companies taking a progressive stance on governance issues, the measurement of the percentage of women on corporate boards of directors, has been standard practice for ESG-minded investors for over a decade. But has all this talk delivered in terms of on-the-ground outcomes for women in the workforce? The results are mixed at best.

The Benefits of Gender Diversity

One of the hot topics in responsible investment today is the concept of double materiality. This concept, key in European sustainable finance regulation, implies that ESG data should be used not only to judge the potential financial implications of ESG risks TO a company, but also to form judgments about the impacts OF a company’s activities on the environment and society. Criteria related to gender diversity can be surprisingly influential in this discussion.

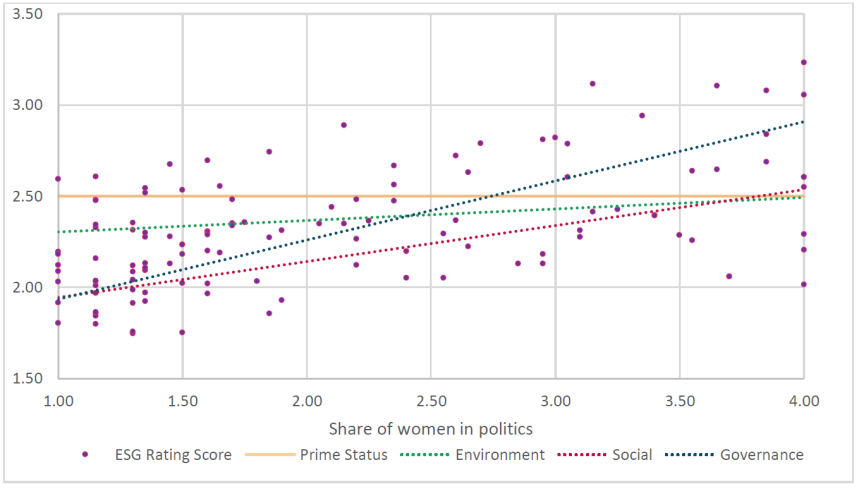

Research by the ISS ESG Country Rating team suggests that countries with a higher proportion of women in senior political roles tend to perform more strongly on ESG metrics.

Figure 1: Countries with a higher share of women participating in politics also tend to have a higher ESG rating score; scores on a numerical scale from 4.0 (highest score) to 1.0 (lowest score)

Source: ISS ESG

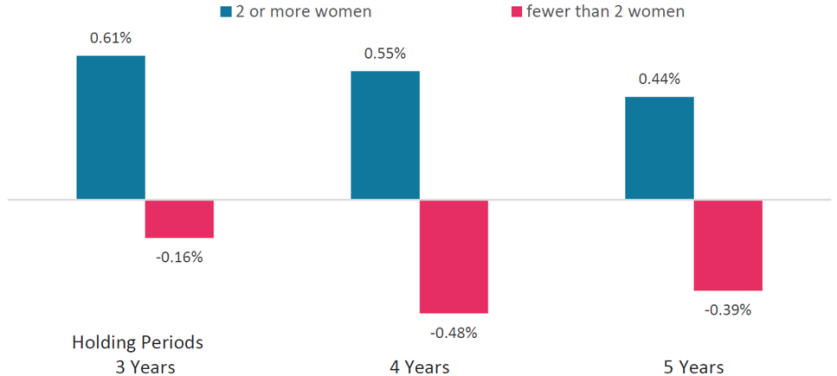

Various measures also demonstrate that strong female representation at senior corporate levels is associated with better financial returns. Recent research illustrates how boards with at least two women outperform the average Russell 3000 returns over 3-, 4-, and 5-year periods, while male-dominated boards underperform the index over the same periods. Over a holding period of four years, the spread between the two groups is greater than 1 percent annually.

Figure 2: Russell 3000: Average Annual Active Return

Source: ISS ESG

Is This Good News Story Translating to Real World Outcomes?

Many of the world’s boardrooms have traditionally been dominated by ‘male, pale, and stale’ boards, that is boards composed entirely of male, white, and long-tenured individuals. Various jurisdictions around the world have taken steps to promote diversity in the boardroom, with notable examples including California in the United States, Spain, and more recently Korea in 2022. Are these regulatory efforts improving metrics related to women’s economic empowerment, however? One of these key metrics is the gender pay gap.

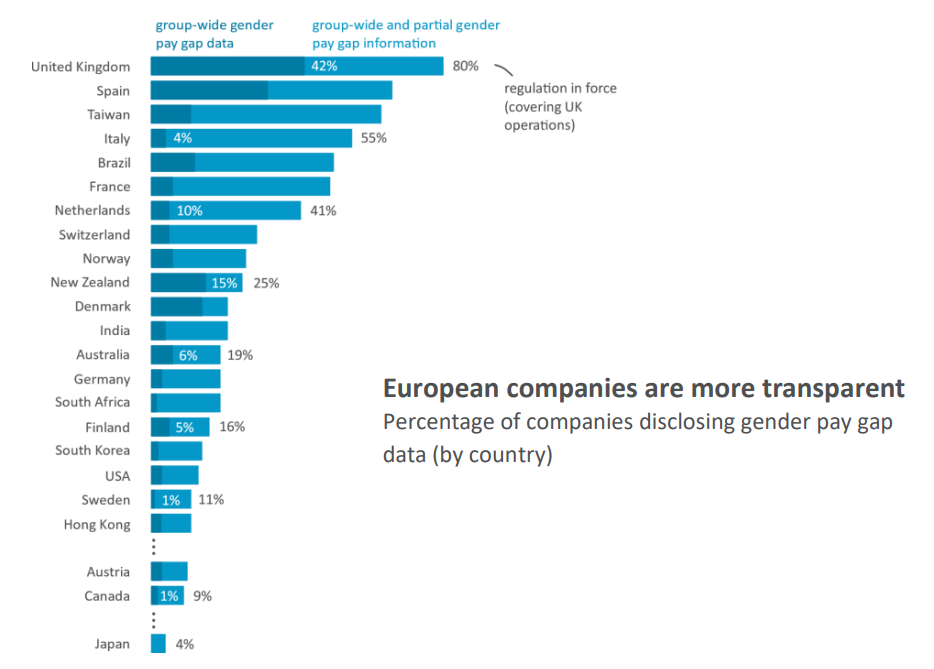

The EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) specifically identifies the ‘unadjusted gender pay gap’ as one of the indicators that investors should be mindful of under the SFDR. It is important for investors operating under the SFDR to be able to report on the Principle Adverse Impacts (PAI) associated with their holdings. There is more work to be done on the disclosure front if these objectives are to be met—only 5.9% of companies globally disclose gender pay gap data for their entire operations, and 20.3% disclose a limited amount of information on the topic. Given the regulatory pressures they face, it is little surprise that European companies feature among the top performers.

Figure 3: Group-wide/Partial Pay Gap Data Disclosure

Source: ISS ESG

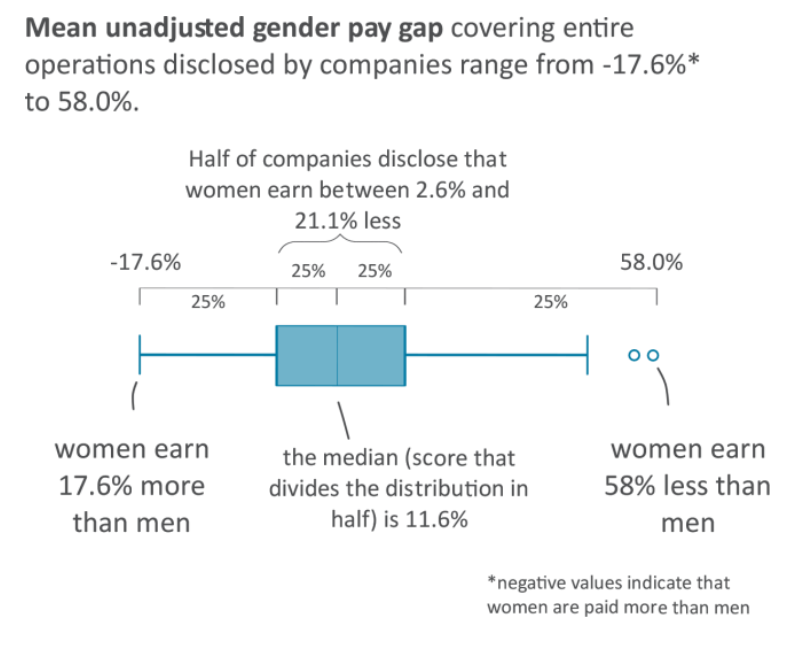

In practice, the bulk of female employees are earning less than men—half of the companies disclose that women are earning between 2.6% and 21.1% less than men.

Figure 4: Mean Unadjusted Pay Gap Data

Source: ISS ESG

There is perhaps some irony in the fact that while it will be the Financials sector calling companies to account under the SFDR and PAI regulations for their performance in relation to women’s economic empowerment, the Finance sector is itself the worst performer on this measure.

Figure 5: Unadjusted Gender Pay Gap by Sector

Source: ISS ESG

Conclusion

The responsible investment community has spent years working to improve gender diversity among senior decision-makers at listed companies. While these efforts have been associated with positive financial outcomes, to date they are yet to make a significant dent in the key underlying issue of gender pay gaps. In 2022 responsible investors should prepare for a more outcomes-focused approach from regulators and stakeholders anxious to ensure that the real-world situation is improved for female employees.

Print

Print