Michael Klausner is the Nancy and Charles Munger Professor of Business and Professor of Law at Stanford Law School; Michael Ohlrogge is Assistant Professor at NYU School of Law. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes SPAC Law and Myths by John C. Coates (discussed on the Forum here).

Introduction

SPACs have been widely criticized for their misalignment of sponsor and shareholder interests and for the dilution inherent in their structure. A major source of these problems is the sponsor’s “promote,” under which sponsors receive 20% of post-IPO shares essentially for free. Earnouts, which cancel promote shares if post-merger price targets are not met, have been recently pitched as a solution to these problems. In their SEC filings, SPACs describe earnouts as aligning incentives and reducing dilution. Commentators have similarly touted earnouts. In its recent Multiplan decision, the Delaware Chancery Court also raised the possibility that an earnout covering all of a sponsor’s promote might cure SPACs of the inherent conflict of interest between sponsors and shareholders.

In a recent study, however, we find that sponsor earnouts, as currently structured, do little either to algin incentives or to reduce dilution. SPAC proxy statements that state or imply otherwise are misleading. We show that earnouts could be restructured to improve their effectiveness, but substantial misalignment and dilution would still remain, and we propose a framework for accurate disclosure of earnouts to investors. In this post, we address only the impact of earnouts on the alignment of sponsor and shareholder interests.

Misalignment of Sponsor and Shareholder Interests

The fundamental challenge facing any effort to align SPAC sponsor and shareholder interests is the fact that SPACs must either merge or liquidate; and if they liquidate, sponsors get nothing. The shares that sponsors receive in their promote do not participate in a liquidation, nor do any shares or warrants that sponsors purchase. Thus, although a sponsor will pursue the most valuable merger it can find, it will still prefer a value-decreasing merger over a liquidation. In principle, a merger yielding a penny a share is better for a sponsor than a liquidation. Shareholders, on the other hand, get back their investment of $10 per share plus accrued interest if a SPAC liquidates. They, therefore, would prefer a liquidation over a merger unless the merger will be worth more than about $10 per share. As we show in prior research, experience with SPACs over the past decade shows that they commonly enter into value-decreasing mergers. Average market-adjusted, one-year post-merger returns have been negative for every year in the past decade, with an overall one-year average of negative 25% in excess of the Nasdaq and negative 23% in excess of the S&P 500. The average share price of SPACs that merged in 2021 is currently $6.23—close to a 40% drop from the $10 plus interest that SPAC shareholders could have received if they redeemed their shares. Thus, the concern about sponsor incentives is not hypothetical.

Structure of SPAC Sponsor Earnouts

An earnout is intended to align a sponsor’s interest with shareholder interests when the sponsor proposes a merger to shareholders. It does so by withholding shares from the sponsor unless a SPAC’s post-merger share price reaches specified thresholds. If a SPAC’s post-merger share price does not reach a threshold within the term of the earnout—most commonly five or more years—the corresponding shares are cancelled. Among SPACs that merged from January through June 2021, 33% adopted earnouts. For these SPACs, earnouts typically covered 30-40% of the promote’s total shares.

Challenges of Incentive Alignment

The challenge in aligning sponsor and shareholder interests is that even a bad merger with a promote subject to an earnout is better for a sponsor than a liquidation in which it receives nothing. Shares subject to an earnout remain quite valuable, even when a SPAC enters into a value-decreasing merger. The reason for this is that shares subject to an earnout are an option-like security. Even if a SPAC enters into a merger with a low present value, sponsor shares subject to the earnout retain option value so long as there is some chance that the post-merger share price will rise above $10. This is particularly true where (a) the SPAC’s post-merger share price is highly volatile, as is typical of post-merger SPACs, (b) the threshold share prices are not market-adjusted, which is typical in SPAC earnouts, and (c) where the period to satisfy the earnout’s targets is long, as it typically is.

Earnouts, therefore, cannot align sponsor and shareholder interests perfectly. Nonetheless, we analyze how close they can come. We find that meaningful improvements on the typical earnouts can be made, and that earnouts become much more effective when combined with a large investment by the sponsor at a price of $10 per share.

The Impact of an Earnout on Interest Alignment

To examine how much earnouts improve incentive alignment, we use a Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the present value of a sponsor’s share that is subject to an earnout as of the date of a merger where the merger is worth less than $10 per share. A share subject to an earnout is obviously worth less at the outset than an unencumbered share (though in many cases, the difference in value is not large). What matters most for incentive alignment, however, is how much value a sponsor loses if it proposes a bad merger. On this front, we find that although shares subject to an earnout do lose value if a sponsor proposes a value-decreasing merger, the amount they lose is not much more than the value that unencumbered shares would lose. For instance, suppose a sponsor proposes a merger worth $7.50 per share. In this event, an unrestricted promote share will be worth 25% less than its value in a merger worth $10 per share. By comparison, a share subject to a 5-year earnout with a $20 price target will lose roughly 30% of its value. So, the earnout with a target at the top of the range one typically sees has a fairly small impact on the value of a sponsor’s shares.

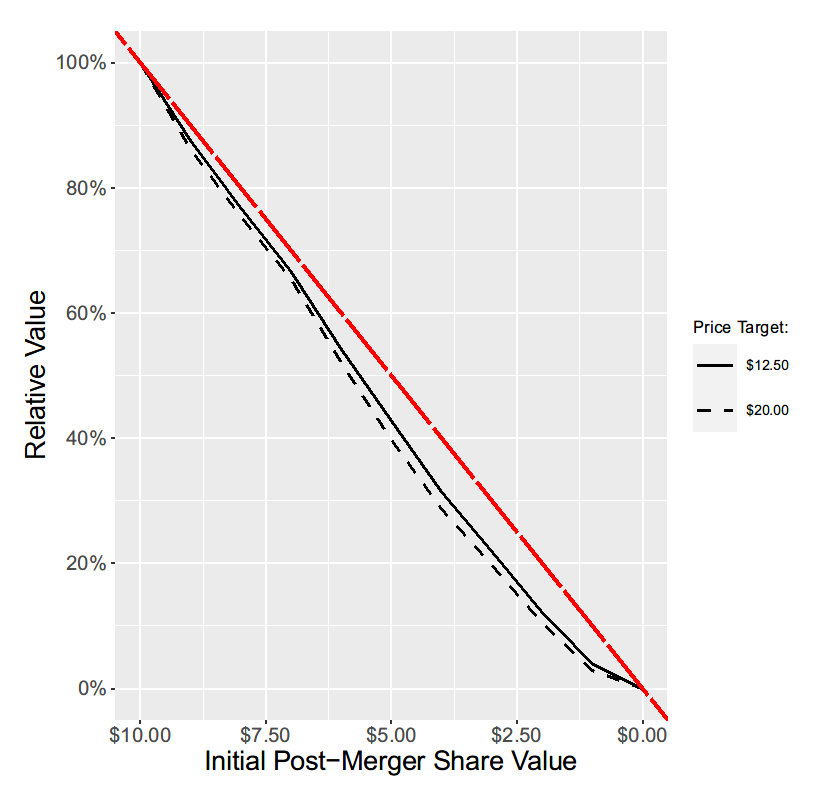

Figure 1, below, systematizes this analysis over a range of earnout price thresholds and post-merger share values. The per-share value of a hypothetical merger is on the x-axis, and the reduction in present value of the sponsor’s shares is on the y axis. As a baseline, the red line shows the value of sponsor shares if they were not subject to an earnout. Those shares, of course, fall dollar-for-dollar as the value of the merger declines. The black lines show the present value of shares subject earnout thresholds of $12.50 and $20. The greater the vertical distance between a black line and the red baseline, the greater the impact of the earnout for each hypothetical value of a merger.

Figure 1 shows that a typical earnout with a five-year duration will have little impact on the present value of a sponsor’s shares compared to a promote that is not subject to an earnout. The closeness of the red and black lines indicates that in the event a sponsor proposes a bad merger, shares subject to an earnout lose only a small amount more value than unrestricted promote shares. Changing an earnout’s price threshold does little to help this. Although, at the outset, a share subject to an earnout with a $20 price target is worth less than a share subject to an earnout with a $12.50 price target, both lose roughly the same percentage of their value if a sponsor proposes a value-decreasing merger. Typical earnouts thus fail to improve the alignment of sponsor and shareholder interests.

Figure 1: Sponsor Promote Value and Post-Merger Share Value (5-Year Earnout)

Improving the Earnout

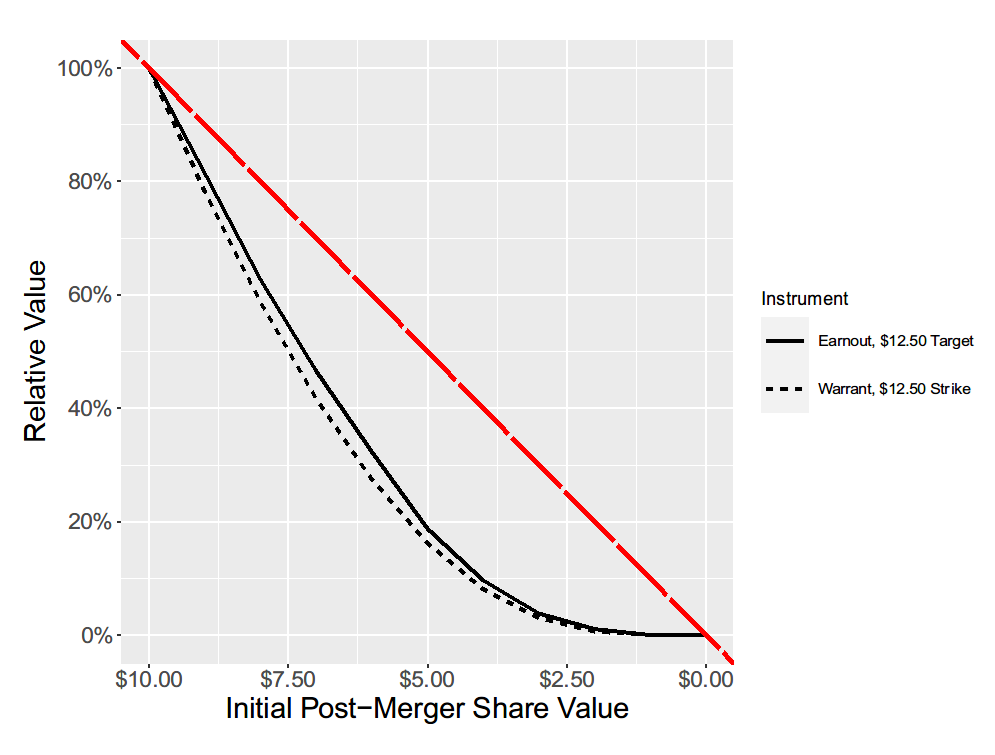

As stated above, an earnout creates an option-like security for a sponsor. As a result, the sponsor derives value from (a) volatility in a SPAC’s post-merger share price, (b) an earnout’s long duration, and (c) the absence of a market adjustment in earnout thresholds. Figure 2 presents the results of the same valuation exercise performed above but with (i) a one-year earnout that will pay out only at the end of its term, and (ii) price thresholds adjusted for changes in market prices. These changes reduce the impact of volatility on the value of an earnout share. For simplicity, we include only a $12.50 threshold. Figure 2 also shows the results of the same analysis with the sponsor receiving warrants with a $12.50 exercise price rather than shares as a promote. If a sponsor holds warrants, a sponsor benefits only to the extent it adds value above a given benchmark, rather than being awarded its entire promote for exceeding an earnout’s price targets by a penny.

Figure 2 shows that, with these changes in the terms of an earnout or with the use of a warrant rather than a share subject to an earnout, sponsors would lose substantially more of their promote if they propose a value-decreasing merger than they would lose under the typical five-year earnout.

Figure 2: 1-Year Earnout and 1-Year Warrant

Figure 2 thus shows that earnouts can be restructured to bring sponsor interests into better alignment with shareholder interests. But even a restructured earnout falls far short of full alignment. In a merger that causes a 25% drop in value to shareholders, the sponsor will still receive roughly 50% of the value of its promote—and that assumes all of the promote is subject to an earnout. So, a SPAC with $200 million in post-IPO equity and a $40 million promote, would provide $20 million in winnings for the sponsor and $50 million in losses for public shareholders.

The Impact of a Sponsor Investment in a Merger

A sponsor can further align its interests with those of shareholders by pre-committing to make a substantial investment in the SPAC at the time of a merger. For instance, suppose a sponsor will receive 4 million promote shares all of which are subject to an earnout that will reduce their value to $5.00 each in the event the sponsor proposes a merger worth $7.50 per share. If the sponsor proceeds with a merger worth $7.50 per share, the promote it receives will thus be worth $20 million, as shown above. Now, suppose the sponsor also makes a large PIPE investment at $10 per share. If the sponsor were to lose $20 million on that PIPE investment in a merger worth $7.50 per share, that loss would wipe out the $20 million profit from the sponsor’s promote. In this case, the sponsor would no longer have an incentive to propose a merger it expects to be worth only $7.50 or less per share.

In Figure 3, below, we systematize this analysis. The x-axis of Figure 3 measures a sponsor’s investment at the time of a merger. We measure the investment as a percentage of the face value of the sponsor’s promote—as though the shares are worth $10 each. So, for example, if the face value of the sponsor’s promote is $40 million, the 100% point on the x-axis would reflect a $40 million investment by the sponsor. The y-axis measures the per-share value of a merger that a sponsor would require in order to favor a merger over liquidation. So, for example, with an earnout having a $12.50 threshold and an investment the same size as the face value of the promote (that is, 100% of the promote), a sponsor would liquidate rather than proceed with a merger if the merger is worth less than $6.25 per share. With a warrant, the sponsor would reject a merger unless it is worth $6.50 per share or more.

Figure 3: Sponsor Incentives to Reject Bad Mergers

As we have said, it is not possible to bring a sponsor’s interest fully into alignment with shareholder interests, but a positive interpretation of these findings is that a restructured earnout, coupled with a sponsor’s pre-commitment to make a large investment in any merger it proposes, can materially improve the alignment of sponsor and shareholder interests compared to the status quo. Many past SPAC mergers have lost SPAC shareholders a lot of money. If an improved earnout coupled with a large, pre-committed investment by a sponsor induces sponsors to liquidate rather than proceed with the worst of deals, this would be a positive development.

Disclosure of Earnouts and Sponsor Economics

We have shown that there is far less than meets the eye in earnouts. As currently structured, they have little impact on the alignment of sponsor and shareholder interests. Some SPACs have nonetheless described their earnouts as creating such an alignment. This is a clear misstatement. Other SPACs provide just a bland description of an earnout’s mechanics with no such commentary. Even this sort of description is deceptive in that the terms of an earnout appear to align interests. Why else would the earnout have been adopted? As we have shown, some analysis is necessary in order to reveal whether an earnout is or is not what it appears to be – and therefore to comply with the SEC’s mandate that SPACs “clearly describe the conflicts of interest” created by SPAC sponsors’ compensation arrangements.

At the time of a merger, a SPAC should disclose quantitatively the extent to which sponsors’ interests align with the interests of shareholders. This must go beyond the typical boilerplate in SPAC proxy statements reciting the fact that the sponsor and the SPAC’s management have interests that are different from the interests of shareholders. At a minimum, SPACs should be required to disclose how far a SPAC’s post-merger share price must fall below $10 for the sponsor to prefer liquidation over a merger. This is the analysis we present above in connection with Figure 3. It should put shareholders on notice regarding how much credence to put into a SPAC board’s recommendation of a merger. For a sponsor with no investment concurrent with a merger, the sponsor would favor a merger over liquidation so long as the merger is worth something above zero. But for a sponsor with a sizeable investment and a well-structured earnout, the breakeven price may be substantially higher.

It is unrealistic to expect SPACs to disclose this information voluntarily. The SEC has already indicated that it is concerned about disclosure of sponsor incentives and dilution, and that it is considering regulations that would address these concerns. We propose that the SEC incorporate disclosure of earnouts into those regulations.

Conclusion

We have shown that, as currently structured, earnouts have a minimal impact on the misalignment of sponsor and shareholder interests in a SPAC. Although an earnout cannot fully create aligned interests, SPACs can improve their misalignment with a combination of a restructured earnout and a precommitment by a sponsor to make a large investment in the merger it ultimately proposes. Whether SPACs choose to improve earnout structures or not, their disclosure must be improved. Current disclosures of earnouts are misleading. Those disclosure practices have been standardized and are unlikely to change without SEC intervention. We therefore propose that the SEC address earnout disclosure in its current effort to propose regulations regarding SPACs.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print