Colleen Honigsberg is an Assistant Professor at Stanford Law School; and Shivaram Rajgopal is the Roy Bernard Kester and T.W. Byrnes Professor of Accounting and Auditing at Columbia Business School. This post is based on a rulemaking petition submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission by The Working Group on Human Capital Accounting Disclosure.

This post is based on a petition submitted by The Working Group on Human Capital Accounting Disclosure, pursuant to Rule 192(a). The Working Group on Human Capital Accounting Disclosure respectfully submits this petition pursuant to Rule 192(a) of the Securities Exchange Commission Rules of Practice. We ask that the Commission develop rules to require public companies to disclose sufficient information to allow investors to assess the extent to which firms invest in their workforce.

Our Working Group is composed of leading academics, former Commission officials, and market participants who focus on the law and economics of human capital management:

- Ralph Richard Banks, Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor of Law at Stanford Law School;

- Paul Brest, Former Dean and Professor Emeritus at Stanford Law School;

- John Coates IV, John F. Cogan, Jr. Professor of Law and Economics at Harvard Law School and former General Counsel and Acting Director of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance;

- Gerald Davis, Gilbert and Ruth Whitaker Professor of Business Administration at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business;

- Joseph A. Grundfest, William A. Franke Professor of Law and Business at Stanford Law School and former SEC Commissioner;

- Colleen Honigsberg, Associate Professor of Law at Stanford Law School;

- Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Pierrepont Family Professor of Law at New York University School of Law and former SEC Commissioner;

- Shivaram Rajgopal, Roy Bernard Kester and T.W. Byrnes Professor of Accounting and Auditing, Columbia Business School;

- Ethan Rouen, Assistant Professor of Business Administration and Faculty Co-Chair, Impact- Weighted Accounts Project at Harvard Business School; and

- Daniel Taylor, Arthur Andersen Professor of Accounting at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and Director of the Wharton Forensic Analytics Lab.

Professors Honigsberg and Rajgopal serve as co-Chairs of our Working Group. We act in our individual capacities; our institutional affiliations are noted for identification purposes only.

We differ in our views about the regulation of firms’ relationships with their employees generally. But we all share the view that investors need additional information to examine whether and how public companies invest in their workforce—and that the Commission’s rules should therefore require that information to be disclosed. Here, we focus on key elements of that information that we all agree are important.

Our post proceeds in three parts. First, we explain why prompt SEC action on this subject is necessary. Second, we draw on accounting principles to describe three straightforward recommendations for reform. Third, we consider potential costs and benefits of those reforms. We conclude that the SEC should promptly develop rules requiring firms to disclose information that will allow shareholders to assess public companies’ investments in their people—just as SEC rules have long facilitated analysis of public companies’ investments in their physical operations.

The Need for Prompt SEC Action on Human-Capital Accounting

Two recent changes in the public-company landscape demand prompt SEC action in this area. [1] First, an increasing proportion of public companies derive much of their value from intangible assets, including human capital—yet roughly only fifteen percent of those firms even disclose their labor costs. [2] Second, an increasing number of public companies report a loss for accounting purposes, making analysis of firms’ operational costs—the most significant of which is likely to be labor—more important than ever to understanding firm value.

1. The Rise of the Human Capital Firm. The twenty-first century has seen the growth of the human capital firm. When the first accounting standard-setter came into existence in the 1930s, [3] the bulk of industries were made up of firms that built, moved, and sold tangible products using tangible assets. [4] Accordingly, the standard setter designed rules that made sense for those firms at that time.

We see the legacy of these rules in accounting today, as different forms of investment are treated differently. Compare the different accounting treatment for a firm’s spending on capital expenditures (i.e., physical property), research, or its people. Should a firm invest in capital expenditures, that property’s value is included as an asset on the firm’s balance sheet and depreciated over time. By contrast, spending on research and labor are typically treated as expenses: they reduce net income in the current period, and they do not appear as assets on the balance sheet. [5]

These legacy rules do not reflect the current reality that the largest firms add value through internally developed intangible assets such as human capital. And while accounting rules have been sporadically updated over time, they have not been sufficiently reimagined to address the changes in the characteristics of today’s public companies. Consider, for example, the increased importance of intangible assets to the value of U.S. public companies. In 1975, two years after the SEC adopted disclosure rules in Regulation S-K requiring companies to report on the total number of employees, intangibles represented 17% of the value of the S&P 500. [6] By 2020, when the SEC adopted reforms to modernize Regulation S-K and require disclosure of human capital resources, intangibles represented 90% of the S&P 500 market value. [7]

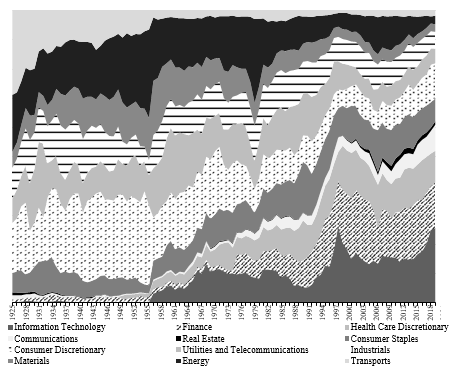

This trend is reflected in Figure 1, which shows that the nature of publicly-traded firms—and the ways they create value—has changed significantly since the creation of the first accounting standard-setter. Two of today’s largest industries, healthcare and information technology (industries which rely heavily on human capital), jointly account for more than 33% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500 despite the fact that they are relatively new industries. [8] Accounting rules, however, have not kept pace, leaving investors without information necessary to accurately value the firms that they own.

Figure 1. The Rise of the Human-Capital Firm.

2. The Increasing Prominence of Lossmaking Public Companies. Moreover, an increasing number of public companies now record a net loss, complicating analysis of their value. [9] Commonly used valuation techniques, such as price-to-earnings ratios, cannot be used to value these firms. Instead, investors must project future earnings—an analysis that requires reliable information on costs, margins, and scalability that is commonly obfuscated under current accounting principles. Accordingly, as we describe below, the Commission should require firms to provide investors with the information necessary to value lossmaking public companies.

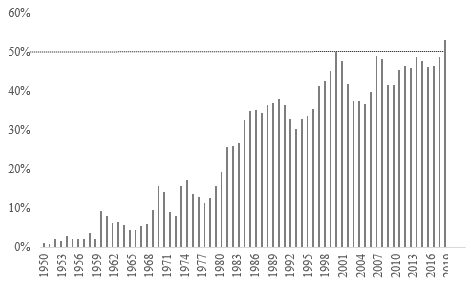

In 2020, more than half of U.S. public companies reported negative earnings. A leading explanation for the growing number of net loss companies is that many of these companies are relatively young, technology-heavy firms, and investors are betting on their future profitability. [10] Figure 2 below shows the increasing prevalence of lossmaking firms among U.S. public companies:

Figure 2. The Increasing Proportion of Loss-Making Firms Among Public Companies. [11]

To best value lossmaking firms, investors need a sufficiently detailed breakdown of the firm’s cost structure to identify contribution margins. That requires distinguishing whether cash outflows should be considered investments or maintenance expenses. [12] For example, the purchase of new equipment that improves the firm’s operational efficiency and contributes to revenue growth can be considered an investment, as that equipment will be used going forward and will create future value. By contrast, the replacement of existing equipment to maintain current levels of revenue can be considered a maintenance expense, as that expenditure allows the firm to maintain its current productivity, but does not increase its productivity.

Existing accounting rules allow investors to estimate, albeit imperfectly, the portion of capital expenditures that can be considered investment and the portion that can be considered maintenance expense, and it is clear that sophisticated investors consider that breakout to be important. For example, skilled investors such as Warren Buffet have long incorporated this information in valuation. [13]

By contrast, when it comes to workforce, investors typically cannot even determine total workforce costs—much less identify the distinction between investments and maintenance workforce expenses. [14] To improve pricing accuracy, investors need the information that will allow them to draw that same distinction for labor costs. As explained below, three straightforward reforms to SEC rules in this area would give investors that information, while aligning with existing accounting frameworks.

Proposed Reforms

As explained above, to accurately value a company, investors must be able to distinguish investments from maintenance expenses. Three straightforward disclosure rules in this area would allow investors to draw that distinction. First, managers should be required to disclose, in the Management’s Discussion & Analysis section of Form 10-K, what portion of workforce costs should be considered an investment in the firm’s future growth. Second, workforce costs should be treated pari passu with research and development costs, meaning that workforce costs should be expensed for accounting purposes but disclosed, allowing investors to capitalize workforce costs in valuation models as appropriate. Finally, the SEC should require greater disaggregation of the income statement to give investors more insight into workforce costs.

1. MD&A Discussion. As noted above, given the importance of labor to the value of today’s public companies and the unique valuation challenges posed by lossmaking firms, SEC rules must give investors the ability to distinguish between labor expenses and an investment in labor. As we have seen with the treatment of capital expenditures, where current rules allow investors to make this distinction, investors find this information valuable.

To allow investors to take this same approach for human capital, managers should discuss in the MD&A what portion of labor costs they view as an investment and why. This would allow investors better insight as to what portion of labor costs should be capitalized in their own models—and incentivize management to consider employees as a source of value creation.

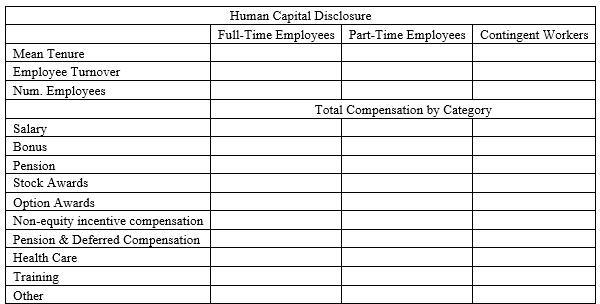

2. Standardized Grid Disclosure. Although management’s view is always helpful, the limits of qualitative disclosures are well-documented. [15] This is particularly true with respect to labor costs. Therefore, we propose that the Commission mandate detailed tabular disclosure to provide investors with significant insight on the types of compensation.

This type of disclosure is necessary because different labor-related expenditures are more likely to reflect investments than others. For example, employee training costs seem likely to be considered an investment. Equity compensation, too, seems more likely to be classified as an investment, given the evidence that providing employees with equity compensation significantly improves retention. [16]

Policymakers have increasingly realized that investors need more granular information in this area. As Senator Mark Warner wrote to the Commission in 2018:

Unlike significant physical investments, which are often capitalized, investments in human capital (and R&D investments) are expensed, as if increased worker capability were less useful to a company in successive quarters than a new building. At least R&D is disclosed on its own expenditure line—investors can assess company expenditures on R&D separately from other firm costs. Because human capital is included in administrative expenses, not as a stand-alone item, it is plausible that capital markets punish companies that invest in their workers as if those companies had excessive energy bills. [17]

We agree. Thus, we suggest that the Commission mandate detailed, quantitative disclosure similar to the grid described in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3. Proposed Grid Disclosure for Workforce Investments. [18]

This approach is consistent with the SEC’s and GAAP’s treatment of research and development. Although R&D is expensed under GAAP rules, it is disclosed, allowing investors to assess R&D investments, and it is sufficiently common for investors to capitalize R&D that this process is taught in basic investing and accounting courses.

While we understand some observers’ reluctance to mandate detailed disclosure of this kind, the SEC has long used the combination of qualitative and quantitative disclosure proposed here in the design of its disclosure rules. For example, since 1992 the Commission’s executive-pay disclosure rules have required firms to disclose detailed quantitative information in a summary compensation table. [19] Those rules have sometimes required issuers to generate information solely for the purpose of producing the data in that table. By contrast, issuers must already produce much of the information that would populate our proposed grid for purposes of tax reporting.

Another benefit of the grid proposed above is that it would permit investors, as appropriate, to amortize a firm’s investments in labor. For example, if a firm has investments in labor of $100,000 and employees typically remain at the firm for five years, investors might amortize that $100,000 at $20,000 per year for five years. Therefore, we include turnover and tenure here both to allow for calculation of amortization and because these metrics may well be sufficiently important to warrant disclosure on their own. [20]

3. Income Statement Disaggregation. As noted above, investors in lossmaking firms need information on product margins to estimate future profitability. To do that, investors need detailed information on operating costs, the most important of which is labor, to predict future margins and to determine what portion of cash outflows reflect investment. Without this information, it is difficult, if not impossible, to reliably value these firms, or to stress-test the market’s valuations of a firm using fundamental analysis.

Building off a recent agenda item at U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Council (“FASAC”), [21] and consistent with reporting under International Financial Reporting Standards, [22] the SEC should require labor costs to be disaggregated in public companies’ income statements. This would allow investors to determine what portion of disclosed income statement accounts, such as Cost of Goods Sold, Research & Development, and Selling, General & Administrative, are attributable to labor costs. Disaggregating labor costs in this manner would allow investors to better understand the job function of employees, their expected value creation, and the firm’s reliance on those employees. [23]

Potential Costs and Benefits of Our Proposal

Disclosures are never costless, and we take seriously the Commission’s obligation to consider the costs of a proposal like ours. [24] However, we believe our proposal represents the simplest approach to integrating key components of human capital management in financial reporting, and that the resulting improved price efficiency would outweigh the initial costs of compliance. [25]

- Fit within Existing Frameworks. Our proposal is drawn from, and fits within, current accounting frameworks. Like the accounting treatment of R&D, our proposal leaves to market participants the complex task of assessing and valuing human capital. The proposal does not change accounting for intangibles more generally, and is consistent with the accounting convention of conservatism, which permits companies to capitalize costs (meaning to recognize an asset) only when those costs can be directly linked to future cash inflows. In other words, there is precedent for our approach, and it would not require a reframing of accounting rules more broadly.

- Improved Price Efficiency. Empirical research in finance and accounting provides evidence that the disclosure of labor costs would be beneficial—although, like U.S. investors, that research must rely on a patchwork of small sample and non-U.S. data. [26] A subset of psychology research has also found that investing in employees leads to higher profitability. [27] Thus, standardized disclosure of this information should improve market pricing for today’s publicly traded companies.

- Costs of Disclosure. We have designed our proposal to minimize costs, as we focus on disclosure of information that companies already collect for tax reporting. [28] Further, there are costs to not providing the information, such as reduced price efficiency and the direct costs investors incur to purchase or otherwise acquire human resource data. These costs should be included when considering the costs and benefits of any changes to the SEC’s disclosure regime. [29]

* * * *

Over the past few decades, we have seen an explosion of so-called “human capital firms”—that is, firms that generate value due to the knowledge, skills, competencies, and attributes of their workforce. Yet, despite the value generated by employees, U.S. accounting principles provide virtually no information on firm labor. The Commission should address this lack of transparency by requiring firm managers to (a) discuss what portion of their labor costs should be considered an investment in future firm profitability, (b) disclose information that allows investors to assess a firm’s investment in its workforce, and (c) disaggregate the income statement to show what portion of major expenses are attributable to labor costs.

For these reasons, we urge the Commission promptly to initiate a rulemaking project to develop such rules.

Endnotes

1Our analysis and recommendations are drawn from a forthcoming Article by Professors Honigsberg and Rajgopal, Wage Wars: The Battle over Human Capital Accounting, 12 HARV. BUS. L. REV. (2022). Our recommendations are also consistent with the data sought by the Human Capital Management Coalition, a global group of 36 large institutional owners and asset managers representing over $8 trillion in assets. See Human Capital Management Coalition, Foundational Human Capital Reporting: Taking a Balanced Approach, available at https://www.hcmcoalition.org/foundational-reporting (last visited May 5, 2022); see also Letter to SEC Investor Advisory Committee from Dr. Anthony Hesketh, March 21, 2019, available at https://www.sec.gov/comments/265-28/26528-5180428-183533.pdf (last visited May 5, 2022).(go back)

2Shivaram Rajgopal, Labor Costs Are the Most Pressing Human Capital Disclosure the SEC Should Consider Mandating, FORBES (May 17, 2021).(go back)

3Stephen Zeff, Evolution of US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) 3.(go back)

4In 1925, the largest industries in the S&P 500 were transportation (28.75%), energy (19.48%), consumer discretionary (17.08%), and industrials (10.53%). By 2020, the largest industries were information technology (25.10%), finance (14.89%), consumer discretionary (12.77%), and healthcare (11.21%). GFD Indices – Market Capitalization, GLOB. FIN. DATA. See also Honigsberg & Rajgopal, supra note 1.(go back)

5Although the accounting treatment for research and development has been criticized, it is superior to the accounting treatment given to outlays for labor: at least research and development expenses are disclosed to investors. See infra notes 15-17 and surrounding text.(go back)

6Intangible Asset Market Value Study, Ocean Tomo.(go back)

7Id. This study suggests that intangibles are especially important for U.S. firms; among the other indices examined by Ocean Tomo, the S&P Europe 350 had the highest share of intangible market value, coming in at 75%.(go back)

8GLOB. FIN. DATA, supra note 4. See also Honigsberg & Rajgopal, supra note 1.(go back)

9Honigsberg & Rajgopal, supra note 1.(go back)

10As noted in CEO Today Magazine, “[b]ack in the day, investing in a firm that is not making profits would be considered insane, but the status quo is changing.” Richard Rossington, 5 of the World’s Biggest Companies That Are Making Zero Profit, CEO TODAY.(go back)

11Figure 2 includes firms traded on the New York Stock Exchange, American Stock Exchange, OTC Bulletin Board, NASDAQ-NMS Stock Market, NASDAQ OMX Boston, Midwest Exchange (Chicago), NYSE Arca, Philadelphia Exchange, and Other-OTC.(go back)

12The absence of disclosure breaking down costs into fixed, variable, and semivariable is a concern with accounting principles more broadly. Because labor costs are likely to be firms’ largest operating cost, we propose the SEC first address the lack of disclosure in this area, but the Commission would do well to consider the opacity of cost disclosures more generally.(go back)

13See Letter from Warren E. Buffett, Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc., to the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (Feb. 27, 1987). Cf. Venkat Peddireddy (Sept. 2021) Estimating Maintenance CapEx (distinguishing maintenance and investment capital expenditures, but describing the limitations of the current approach).(go back)

14Press Release, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, SEC Adopts Rule Amendments to Modernize Disclosures of Business, Legal Proceedings, and Risk Factors Under Regulation S-K (Aug. 26, 2020).(go back)

15See, e.g., Bo Cowgill & Eric Zitzewitz, Incentive Effects of Equity Compensation: Employee-Level Evidence from Google (working paper 2015) (documenting retention effects of equity-based incentives).(go back)

16See, e.g., Bo Cowgill & Eric Zitzewitz, Incentive Effects of Equity Compensation: Employee-Level Evidence from Google (working paper 2015) (documenting retention effects of equity-based incentives).(go back)

17Letter from Sen. Mark Warner to Hon. Jay Clayton, Chairman, Sec. & Exch. Comm’n 3 (July 19, 2018); see also id. (calling for “quantitative and qualitative” disclosure requirements in this area).(go back)

18The design of such a grid may benefit from the input of the Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”). Indeed, FASB has designed notes to the financial statements that take a similarly standardized format. However, despite the obvious need for this type of disclosure, we are not aware that FASB has taken any action in this area.(go back)

19SEC, Final Rule: Executive Compensation and Related Person Disclosure (2006), at 17 (noting commentators’ complaint that the mandated tables could be “highly formatted” and “rigid,” and the Commission’s conviction that accompanying “narrative disclosure,” combined with tabular information, could “give context to the tabular disclosure”).(go back)

20See, e.g., Ton Zeynep & Robert S. Huckman, Managing the Impact of Employee Turnover on Performance: The Role of Process Conformance, 19 ORG. SCI. 56, 57 (2008) (finding that “turnover is associated with decreased store performance”); James C. McElroy et al., Turnover and Organizational Performance: A Comparative Analysis of the Effects of Voluntary, Involuntary, and Reduction-in-Force Turnover, 86 J. APPLIED PSYCH. 1294, 1297 (2001) (suggesting that “turnover has undesirable consequences for organizational performance”); Michael C. Sturman, Searching for the Inverted U-Shaped Relationship Between Time and Performance: Meta-Analyses of the Experience/Performance, Tenure/Performance, and Age/Performance Relationships, 29 J. MGMT. 609, 626 (2003) (identifying non-linear relationships between tenure and performance across different types of jobs); Aneel Iqbal, Shiva Rajgopal, Anup Srivastava & Rong Zhao, Value of Internally Generated Intangible Capital (January 2022); John R. Graham, Jillian Grennan, Campbell R. Harvey & Shiva Rajgopal, Corporate Culture: Evidence from the Field (April 2022) (suggesting that turnover is the biggest determinant of good and bad corporate culture).(go back)

21Meeting Recap, FIN. ACCT. STANDARDS BD. (Sept. 30, 2021).(go back)

22European accounting standards require that firms disclose personnel expense. See IAS 19 Employee Benefits, IFRS.(go back)

23As an example, consider Microsoft’s reporting from the early 2000s. In the Employee Stock and Savings Plan footnote, Microsoft presented pro forma disclosures showing the effect of expensing stock options on different operating expenses. The 2003 Annual Report showed that, if it were to expense stock options, operating expenses would have been nineteen percent higher in total. The allocation was not spread evenly across different expenses. Cost of revenue would have increased by only seven percent, but research and development would have increased by forty-two percent! Microsoft Corp., Annual Report (Form 10-K), Note 16 to Financial Statements. Unfortunately, Microsoft ceased reporting this information after its fiscal year 2003.(go back)

24We note that examining only the costs of disclosure mandates is generally not the approach the law requires the SEC to undertake when considering whether to pursue such mandates. Instead, the Commission’s task is to examine a proposed rule’s effects on “efficiency, competition and capital formation,” National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-290, § 106, 110 Stat. 3416 (1996), including any offsetting benefits associated with the rule.(go back)

25See, e.g., Hesketh, supra note 1 (“[t]he possible future benefits from greater human capital disclosure far outweigh the costs…Only a very small increase in operating performance (several basis points) is required to cover any additional costs incurred though human capital disclosure. Significantly, the vast majority of firms already undertake significant audits of their payroll systems thereby reducing the need to attract any additional costs for reporting purposes”).(go back)

26See, e.g., Andres Donangelo et al., The Cross-Section of Labor Leverage and Equity Returns, 132 J. FIN. ECON. 497, 499 (2019) (finding that firms that have relatively high labor costs have higher expected returns); Ethan Rouen & Matthias Regier, The Stock Market Value of Human Capital Creation (Harv. Bus. Sch., Working Paper No. 21-047, 2020) (providing evidence that firms that invest in their employees have abnormally high returns going forward); Alex Edmans, Does the Stock Market Fully Value Intangibles? Employee Satisfaction and Equity Prices, 101 J. FIN. ECON. 621, 638 (2011) (finding that “firms with high levels of employee satisfaction generate superior long-horizon returns”); Lynn Rees & David M. Stott, The Value-Relevance of Stock-Based Employee Compensation Disclosures, 17 J. APPLIED BUS. RSCH. 105, 114 (2001) (finding that employee stock option expenses are related to firm value); Eli Amir & Gilad Livne, Accounting for Human Capital When Labor Mobility is Restricted 26-27 (Feb. 25, 2000).(go back)

27See generally Suzanne J. Peterson & Fred Luthans, The Impact of Financial and Nonfinancial Incentives on Business-Unit Outcomes over Time, 91 J. APPLIED PSYCH. 156 (2006) (finding, using an experiment that randomly assigned fast-food franchises to control, “financial incentives” or “non-financial incentives” groups, that the franchises assigned to the financial incentives condition outperformed the control group for gross profit, drive-through times, and employee turnover); Chad H. Van Iddekinge et al., Effects of Selection and Training on Unit-Level Performance Over Time: A Latent Growth Modeling Approach, 94 J. APPLIED PSYCH. 829 (2009) (finding that employee training is positively and significantly related to customers’ experience, and that change in customers’ experience was positively and significantly related to changes in profits).(go back)

28Comment letter from the Human Capital Management Coalition, March 22, 2019 (last visited May 5, 2022) (“Many U.S. companies track basic workforce data like labor costs for administrative purposes such as processing payroll. Human resources analytic tools developed in-house and services like ADP, SAP, Oracle, and Workday are commonly utilized to assist with data collection. Firms could leverage the human resources tools and services they already use to satisfy new human capital reporting requirements”).(go back)

29See, e.g., JUST Capital, Feb. 17, 2022, Investors Are Turning Their Focus to Human Capital. But How Hard Is It to Find and Interpret Data? (reporting that it took a team of two over 130 hours to collect data for 28 human capital metrics at 100 companies).(go back)

Print

Print