Eric Ohrn is an Associate Professor of Economics at Grinell College. This post is based on his recent paper, forthcoming in the American Economic Journal. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Pay Without Performance: The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation and Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem both by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Jesse M. Fried.

Corporate Tax Breaks Increase Executive Compensation

Over the past 40 years, the value of compensation packages awarded to corporate executives in the US has risen dramatically. At the same time, a less well-known trend has shaped the US economy: in the presence of increased pretax corporate profits, effective corporate income tax rates have decreased significantly.

These trends motivate an obvious, but empirically unaddressed question: Do corporate tax breaks increase executive compensation? There is, of course, mechanical reason to believe this relationship exists. Corporate tax breaks increase after-tax income that can be used to increase executive compensation via either a competitive market for managerial talent or rent capture by the executives.

Understanding whether and to what extent tax breaks are used to increase executive compensation is important as policymakers, ostensibly, design corporate tax breaks to incentivize desired behaviors such as job creation, capital investment, or the adoption of clean energy sources, rather than to pad the pockets of corporate executives. Answers to these questions are also timely as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) has accelerated the decline in effective corporate tax rates in the US and placed additional downward pressure on corporate tax rates worldwide.

In a new study, I address this question by measuring the effect of two recent US federal corporate tax expenditures (or “breaks”) on the value of compensation awarded to executives at large publicly traded corporations. I find both corporate tax breaks significantly increase executive compensation. I estimate that for every dollar generated by the tax breaks, compensation of the top five highest paid executives at publicly traded US firms increased by 17 to 25 cents.

The Tax Breaks

The first tax break I study, bonus depreciation, allows firms to deduct an additional percentage of the purchase price of new capital assets from their taxable income in the year they are purchased. This decreases the after-tax present value cost of new assets and dramatically decreases the current tax bill of firms that purchase large amounts of capital. I find that a one percentage point decrease in the cost of new investments due to bonus depreciation increases executive pay by 6.2%. Comparing the cash benefits of bonus depreciation to the compensation response at the average firm suggests that for every dollar generated by bonus depreciation, compensation of top executives increases by 25 cents.

The second policy I study, the Domestic Production Activities Deduction (hereafter DPAD), allows firms to deduct a percentage of the income derived from domestic manufacturing activities from their taxable income. The DPAD decreases taxes paid by up to 3.15 percentage points, increasing after-tax cash flows substantially for domestic manufacturing firms. My preferred estimates suggest a one percentage point reduction in effective corporate income tax rates generated by the DPAD increases executive compensation by 4.2% or by 17 cents for every dollar of tax break.

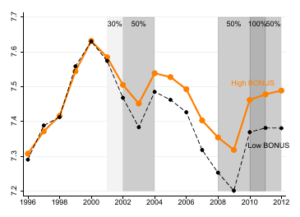

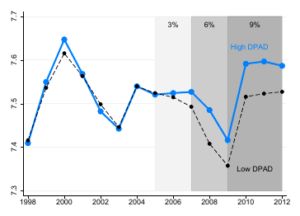

To estimate these effects, I rely on detailed compensation data from the Execucomp database, well-established quasi-experimental variation in each tax break, and a modified difference-in-differences empirical framework. To identify the effect of bonus depreciation, I compare executives in industries that, on average, invest in long-lived assets to executives at firms in industries that invest in short-lived assets. As long-lived assets are typically deducted from taxable income more slowly, bonus depreciation decreases the after-tax present value cost of these assets more than short-lived assets that are deducted more quickly. To identify the effect of the DPAD, I compare executives in industries where a large portion of income is derived from domestic manufacturing — and therefore eligible for the DPAD — to executives in industries where only a small amount is classified as such. Comparing executives and their compensation packages across these dimensions as the policies are implemented and scaled yields difference-in-differences estimates of the effect of each policy.

The graphs below display a visual representation of the research design. In each figure, I plot the log of total compensation for executives in the industries that benefit most from the tax breaks against compensation for executives in industries that benefit less as the policies are implemented and scaled.

Figure 1: Effect of Tax Breaks on Log Compensation

(a) Bonus Depreciation

(b) DPAD

Mechanisms

To better understand whether and by how much the tax breaks affect executive compensation, I design a number of tests to explore the mechanisms at play. One possibility is that the effect is purely due to performance-linked pay in the sense that the tax breaks increase stock prices or measures of firm performance and that compensation contracts are based on these measures. I find that directly controlling for the most common performance measures used in compensation contracts—earnings per share, total sales, total operating income, and sales growth relative to the industry average has little effect on either estimate, suggesting this performance-linked mechanism is not driving the estimated effects.

Next, I explore whether the increase in pay is due to a highly competitive market for scare managerial talent. A number of results suggest this is not the case. First, I show that the effects of the tax breaks are not concentrated among newly hired executives, where the effects of extra resources to bid for talent are most likely to be observed. Second, the effects are also not concentrated in industries with large firms where executive talent is most valuable. Finally, compensation effects are larger in industries that make more hires from inside the firm. These are exactly the type of industries where a highly competitive market is unlikely to develop because executive talent is firm-specific and executives cannot be hired from other firms.

The third possible mechanism I consider is rent extraction by high powered executives. In support of this mechanism, I find the effects of the tax breaks are concentrated among firms with weaker governance structures. More precisely, I test whether the effects of the tax breaks are larger among firms (1) with charters and bylaws that better protect managers from shareholder discipline, (2) with a smaller percentage of shares held by the single largest institutional investor, and (3) with higher average executive tenure. For firms with strong governance scores in at least two of these three metrics, I estimate a null effect of the tax breaks on executive pay, suggesting strong corporate governance can fully mitigate the compensation effects of the tax breaks.

Finally, I investigate whether the pay increases are designed to incentivize value-maximizing responses to the tax breaks on the part of the executives. While the tax breaks seem to result in some increased pay-performance sensitivity which may constitute evidence of this mechanism, I also find that increased firm performance in response to the tax breaks is not concentrated among firms that saw the largest pay increases. Overall, the results across all of these tests point toward rent extraction as the primary mechanism by which the tax breaks precipitate increases in executive pay.

Conclusion

Overall, my results lead to two important conclusions. First, corporate tax breaks lead to large increases in pay for top executives at publicly traded US corporations. Second, rent extraction on the part of high-powered executives plays an important role in the determination of executive compensation.

The complete paper is available for download here.

Print

Print