Ian A. Nussbaum is a partner, Bill Roegge and Meredith Klionsky are associates at Cooley LLP. This post is based on a memorandum by Mr. Nussbaum, Mr. Roegge, Ms. Klionsky, and Mr. Nimetz. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Untenable Case for Perpetual Dual-Class Stock (discussed on the forum here) and The Perils of Small-Minority Controllers (discussed on the Forum here) both by Lucian Bebchuk and Kobi Kastiel.

The rise of founder-led, venture capital-backed companies in recent years has coincided with a surge of companies implementing dual-class share structures in connection with their initial public offerings. A dual-class structure typically entitles the holders of one class of the company’s common stock (often designated as Class B common stock) to multiple votes per share and the class of common stock offered to the public (often designated as Class A common stock) to a single vote per share. In a small number of cases, a class of common stock is offered to the public that has no voting rights at all. Allocating high-vote shares to a class of stockholders – typically the founders, a combination of founders and pre-IPO investors, or all pre-IPO stockholders (including holders of equity granted under employee equity plans and warrantholders) – allows those stockholders to maintain majority voting control after completion of the company’s IPO, while, over time, a majority of the company’s economic ownership becomes widely dispersed among new public stockholders. Prominent dual-class companies include Alphabet, Meta Platforms, Snap and Lyft.

There are compelling rationales for adopting a dual-class structure, but even proponents of the structure generally acknowledge that these benefits are significantly mitigated once the dual-class shares are out of the hands of the founders and/or pre-IPO stockholders. Accordingly, the charters of companies with dual-class structures often provide that any “transfer” (broadly defined) by the original high-vote stockholders will result in automatic conversion of the transferred shares into the company’s ordinary, low-vote shares. [1] Unfortunately, these broadly worded transfer provisions can have significant unintended impacts on M&A transactions involving these companies by making it unclear whether a high-vote stockholder could enter into a voting agreement [2] in support of the transaction without triggering an automatic conversion of that holder’s high-vote shares to low-vote shares. [3]

A review of charters adopted by dual-class tech companies that went public in 2020 and 2021 suggests that companies (and their legal counsel) have become cognizant of this issue, as the vast majority of those charters contain an explicit carve out to the transfer restrictions, permitting high-vote stockholders to enter into voting agreements in connection with an M&A transaction approved by the company’s board. [4] However, such exceptions were not universal and, as will be discussed below, the vast majority of dual-class charters adopted before 2016 that contained transfer restrictions did not include M&A voting agreement carve outs.

This post is intended to convey the importance of allowing founders and other high-vote stockholders in dual-class companies to contractually support an M&A transaction requiring a stockholder vote that has been approved by the company’s board without triggering an automatic conversion of their high-vote shares to low-vote shares under the transfer provisions of the company’s charter. We explain how transfer provisions have evolved in recent years – particularly in light of litigation – and provide recommendations for dual-class companies to consider to avoid unintended consequences that may unnecessarily hinder a potential M&A transaction. We also offer potential alternatives for dual-class companies considering M&A transactions when amending the company’s charter is not a viable option.

We recommend that all pre-IPO dual-class companies include voting agreement carve outs in their charters effective upon the consummation of their IPOs. While the specific language should be tailored to each issuer, this sample language could be included in dual-class charters:

“… the following shall not be considered a “Transfer” […]: […] entering into, amending, modifying, or reaching an agreement, arrangement or understanding regarding, a support or similar voting or tender agreement (with or without granting a proxy) in connection with a direct or indirect merger, consolidation, asset transfer, asset acquisition, share transfer, liquidation, dissolution or similar transaction involving the Company that has been approved by the Company’s Board of Directors (regardless of whether the Board of Directors later changes its recommendation with respect to such transaction).”

In addition, currently public dual-class companies with transfer provisions that do not contain clear carve outs for the delivery of voting agreements in the M&A context should discuss with their advisers the possibility of adopting “clear day” amendments to their charters to include these carve outs.

Voting agreements in public M&A transactions

The sale of a publicly traded company in the US will generally require the approval of the holders of a majority of the voting power of the company’s outstanding shares as a precondition to the sale’s completion. [5] Accordingly, definitive agreements for public company acquisitions almost universally contain a condition to the closing of the transaction that such stockholder approval has been obtained. In most cases, obtaining stockholder approval will take at least two months after the announcement of the transaction, during which time the risk of an interloping bidder submitting a topping bid to acquire the company can be significant. [6]

As a result, it is customary for the target company in public company sale transactions to agree to a series of “deal protection” covenants in favor of the acquirer intended to reduce the likelihood that stockholder approval will not be obtained, including requirements that, subject to certain fiduciary exceptions:

- The target company’s board of directors recommend that its stockholders approve the transaction.

- The target company’s board of directors will not adversely change that recommendation, subject to limited exceptions.

- The target company refrains from soliciting, or engaging in discussions with respect to, third-party proposals for the target company.

- Afford the acquirer certain notice and match rights if a topping bid does emerge.

In addition to these customary deal protection provisions, if the target company has directors, officers or other significant stockholders [7] that hold securities representing a meaningful percentage of its outstanding voting power, the acquirer will typically require those stockholders to deliver voting and support agreements concurrently with the execution of the definitive agreement for the transaction. These voting agreements typically commit the signatories to vote in favor of the transaction and against any alternative transaction, and restrict the signatories from transferring their shares prior to the stockholder meeting to approve the transaction, but otherwise permit the signatories to vote their shares on other matters coming before the stockholders of the company as each signatory sees fit. Voting agreements typically terminate upon the termination of the definitive agreement for the transaction, if the definitive agreement is modified in a manner adverse to the signatory and, in most (but not all) cases, if the target company’s board of directors changes its recommendation in support of the transaction in accordance with the definitive agreement. [8] Given these provisions, the transfer of voting control embodied in a customary voting agreement is limited in duration and scope.

In circumstances where voting agreements are appropriate, acquirers typically view them as among the most critical deal protection devices. If an individual or group of insider stockholders holds a majority or near majority of the company’s voting power, the acquirer may refuse to enter into the transaction without such voting agreements in place, as doing so would be tantamount to granting the insider stockholder(s) an option on whether to proceed with the transaction or vote it down (for example, to accept a superior proposal), even if the board of directors of the target company continues to support the transaction. [9]

Given their significant – often controlling – voting power and insider status, the high-voting stockholders of dual-class companies are a prototypical example of the stockholders typically required to deliver voting agreements in public company M&A transactions. However, dual-class companies are often surprised to discover an unexpected barrier to their founders or other high-vote stockholders delivering a voting agreement: the anti-transfer provisions of the charter.

Evolution of voting agreement carve outs in dual-class charters

Base transfer restriction

A typical dual-class charter provides that, subject to specified exemptions, any “transfer” (broadly defined) of the high-vote shares will trigger an automatic conversion of the transferred shares into low-vote shares, including “the transfer of, or entering into a binding agreement with respect to, [the power (whether exclusive or shared) to vote or direct the voting of such share by proxy, voting agreement or otherwise]” (emphasis added). The entry into a voting agreement would therefore, on the face of the provision, appear to constitute a “transfer” that would trigger auto-conversion to low-vote shares. While the intent of the anti-transfer provisions is to prevent permanent transfers of voting power over the high-vote shares (in keeping with the overall theory that the high-voting power is primarily justifiable while in the hands of the founder and other early stockholders), absent an applicable carve out, advisers to a holder of high-voting shares of a dual-class company with such a charter would be unable to assure the holder that this argument would prevail over the plain language of the charter if entry into an M&A voting agreement were to be litigated, even though the “transfer” of voting power in a voting agreement is limited in scope and duration.

We now turn to the exceptions in dual-class charter transfer provisions that may be available to eliminate this risk.

Potential carve outs for M&A voting agreements

During the first wave of venture-capital backed dual-class company IPOs, roughly starting with Google’s IPO in 2004, the exceptions to the anti-transfer provisions generally fell into three categories:

- Transfers to trusts and other legal entities (generally in connection with the holder’s tax or estate planning) that do not result in the holder losing control over the disposition or voting of the shares.

- Pledges of the shares as collateral for a loan obtained by the holder (but not foreclosure on the collateral).

- Limited transfers of voting rights for ministerial or nonrecurring purposes, including the grant of a proxy by the dual-class stockholder to the company’s directors or officers in connection with actions to be taken at a stockholder meeting.

Other permitted exceptions were possible but less common, including, controversially, transfers to the holder’s family members. [10]

Modern dual-class charters retain these base carve outs, but over time have also added additional carve outs to address issues and ambiguities that arose from the earlier dual-class charters, including the issues that are the subject of this post.

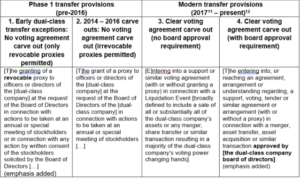

The table below sets forth the most applicable carve out to permit the delivery of a voting agreement from four different dual-class charters, each of which contains a base transfer restriction substantively consistent with the base transfer restriction described above.

M&A voting agreement carve outs in dual-class company charters

We refer to transfer provisions of the type shown in columns 1 and 2 above, which do not expressly carve out the delivery of voting agreements in connection with M&A transactions, as “phase 1 transfer provisions.” The phase 1 transfer provision in column 1 is the least favorable, as most acquirers would not accept a revocable proxy as a form of voting support because by definition the proxy could be unilaterally revoked before the stockholder vote. The potential for the use of an irrevocable proxy as a support arrangement to take advantage of the exception in column 2 is discussed later in this post.

As seen in the table above, beginning with 2016-vintage IPOs (including Snap, one of the most high-profile dual-class IPOs of the year), dual-class companies began addressing the ambiguities in phase 1 transfer provisions by expressly permitting voting agreements in the context of M&A transactions. The primary distinction between modern voting agreement carve outs (columns 3 and 4) is whether the board of directors of the dual-class company is expressly required to have approved the transaction in respect of which the voting agreement is being delivered. Including such an approval requirement is intended to effectively preclude the high-voting stockholder from committing to support a hostile bidder for the dual-class company until such time as the board of directors has approved the transaction.

Stockholder litigation

As always, ambiguity begets litigation. Take, for example, the acquisition of Inovalon Holdings, a dual-class company that completed its IPO in 2015, by a consortium of private equity investors. In connection with the execution of the merger agreement in August 2021, Inovalon’s founder – and holder of high-vote shares – entered into a customary voting agreement with the acquirer, including the requirement to vote in favor of the transaction and against any alternative transaction and not to transfer any shares until the termination of the voting agreement (including upon the termination of the definitive agreement for the transaction). Not surprisingly, given when Inovalon completed its IPO, its charter contained a phase 1 transfer provision with a voting agreement carve out consistent with the carve out set forth in column 2 of the table above. However, that carve out did not address the delivery of a customary M&A voting agreement of the type entered into by the Inovalon founder – to use the carve out, the founder would have had to deliver an irrevocable proxy in support of the transaction to one of Inovalon’s directors or officers.

In October 2021, stockholders of Inovalon brought suit in the Delaware Court of Chancery claiming that, by executing the voting agreement, the founder’s high-vote shares automatically converted to low-vote shares, an event that was not described in the company’s proxy statement. The plaintiffs sought a declaration that the shares had been converted and an injunction enjoining the stockholder vote until an accurate proxy statement could be issued. In order to avoid having to delay Inovalon’s special meeting to approve the transaction to litigate the plaintiffs’ claims, the parties agreed with the plaintiffs that, unless the transaction was approved by holders of Inovalon shares sufficient to approve the transaction – assuming that the auto-conversion had in fact occurred – Inovalon would not close the transaction until the Delaware Court of Chancery had ruled on the plaintiffs’ complaint. In other words, Inovalon and the acquirer were forced to agree to act as though the voting agreement had not been entered into. While Inovalon’s stockholders ultimately approved the transaction in sufficient numbers to satisfy this requirement, if they had not, the consummation of the transaction would have been subject to the resolution of the plaintiffs’ claims in the merits, which could have significantly delayed, or even prevented, closing. Ultimately, the plaintiffs’ firms were awarded $1.9 million in fees and expenses in connection with the disposition of the action, meaningfully in excess of the typical “mootness” fee for public M&A transactions, which one paper estimated as usually in the range of $50,000 to $300,000.

We also have seen plaintiffs’ firms use voting agreements delivered by high-vote stockholders as a basis for Delaware General Corporation Law (DGCL) 220 books and records demands, which enables the plaintiffs to review the books and records of the subject company in an effort to uncover bases for additional, unrelated claims.

These strategies adopted by plaintiffs’ firms underscore the importance for practitioners to include a specific carve out in the transfer provisions allowing high-voting stockholders to contractually support change-of-control transactions.

Best practice: Include a carve out in your transfer provisions

To avoid potential litigation that may attempt to enjoin a merger or, at a minimum, entail significant costs and the injection of uncertainty into the transaction, we propose incorporating a bright-line exception into dual-class charters permitting high-vote stockholders to enter into voting agreements in connection with change-of-control transactions to eliminate the risk of claims that delivery of the voting agreement resulted in an automatic conversion of the underlying high-voting shares. Such an exception should not be objectionable, particularly because it does not turn the tide in favor of the “investor” or “founder” in any way and, in fact, promotes the alienability of these shares when there is alignment around the table.

We propose that the following language be included in dual-class charters:

“… the following shall not be considered a “Transfer” […]: […] entering into, amending, modifying, or reaching an agreement, arrangement or understanding regarding, a support or similar voting or tender agreement (with or without granting a proxy) in connection with a direct or indirect merger, consolidation, asset transfer, asset acquisition, share transfer, liquidation, dissolution or similar transaction involving the Company that has been approved by the Board of Directors (regardless of whether the Board of Directors later changes its recommendation with respect to such transaction).”

As a best practice, this language should be included in the charter when the dual-class company goes public. Companies with phase 1 transfer provisions also should evaluate with their counsel whether it may be appropriate to seek stockholder approval for an amendment to the company’s charter to update the transfer provisions on a “clear day” when no change-of-control transaction is contemplated. [13] In cases where the dual-class company is otherwise seeking stockholder approval for an amendment to the charter (for example, for companies pursuing charter amendments to expressly provide for the exculpation of officers under DGCL 102(b)(7), as discussed in this Cooley PubCo blog post), this may be advisable, although dual-class companies should carefully weigh the pros and cons of this approach with their advisers in light of the scrutiny that the proxy advisers and other market participants afford dual-class companies.

Practice pointers for dual-class companies with phase 1 transfer provisions

So what should a dual-class company with a phase 1 transfer provision do if it is considering entering into a business combination transaction that requires the approval of its stockholders and the counterparty seeks a voting agreement? There is no one-size-fits-all approach: Each dual-class company will need to, in close consultation with its advisers, design the best solution available under the circumstances. We’ve outlined here some considerations for dual-class companies when designing this solution.

The percentage of voting power controlled by the high-vote stockholders

The higher the percentage of the voting power controlled by the high-vote stockholders, the more likely it is that the counterparty to the transaction will require a strong commitment from the high-vote stockholders as a condition to transacting.

Whether the dual-class company is the seller or acquirer in the transaction

If the dual-class company is the seller in the transaction, arguably the risks to the high-vote stockholder are lower because as long as the transaction closes, the high-vote stockholders will exchange their shares for the transaction consideration. As seen in the Inovalon litigation, however, the risk of a deemed automatic conversion still presents significant risks to the dual-class company and the certainty of closing the transaction, even on the sell side. On the other hand, if the dual-class company is the acquirer and an acquirer stockholder vote is required in connection with the transaction, its high-voting stockholders will expect to continue to hold their high-voting shares after the closing of the transaction and so will likely be less willing to accept the risk of an inadvertent automatic transfer than in a sale transaction.

The dual-class company’s overall leverage in the transaction

As with any other deal term, the greater the dual-class company’s leverage, the more likely that it will be able to dictate a favorable resolution. Accordingly, the dual-class company will have greater latitude if it is running an auction process or if the acquisition is fundamental to the acquirer’s go-forward strategy than if the dual-class company is engaged in a bilateral negotiation.

The risk tolerance of the high-vote stockholder and the dual-class company’s board

As noted above, Delaware courts have yet to rule on how phase 1 transfer provisions should be interpreted in the context of a voting agreement or other support commitment delivered in connection with a business combination transaction. While we and other commentators believe that the delivery of an irrevocable proxy or other, “softer” forms of support should not trigger automatic conversion under phase 1 transfer provisions, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that Delaware courts will adopt a plaintiff-friendly interpretation of these provisions. Furthermore, given the success of the plaintiffs in the Inovalon litigation at creating holdup value, we expect that plaintiffs’ firms will continue to seek ways to assert that automatic conversions have occurred, particularly for dual-class companies with phase 1 transfer provisions, until Delaware courts give definitive guidance on the subject.

The underlying reasons why voting agreements are required in the first place

Remember, counterparties require voting agreements to prevent significant stockholders of the other party from unilaterally determining (or significantly influencing) the outcome of a required stockholder approval for a transaction. Voting agreements are not intended to guarantee that stockholder approval will be obtained, as demonstrated by many voting agreements falling away if the board makes an adverse recommendation change in accordance with the transaction agreement. Accordingly, if a binding voting commitment is not on the table, dual-class companies should think about other “soft” ways to incentivize the dual-class stockholders not to change their votes that fall short of a voting commitment and accordingly pose a lower risk of an inadvertent auto-conversion.

Bearing the above considerations in mind, below are examples of possible approaches a dual-class company with phase 1 transfer provisions could adopt, ranging from most protective of the counterparty and presenting the highest risk of a deemed automatic conversion to least protective of the counterparty and lowest risk of a deemed automatic conversion. In many cases, it may be appropriate for the dual-class company to adopt more than one of these approaches.

Contractual voting commitments

Customary voting agreement

The high-vote stockholders enter into customary voting agreements with the counterparty, including voting commitments and transfer restrictions. This was the approach taken in the Inovalon transaction in spite of Inovalon having a phase 1 transfer provision (with the most favorable carve out of the type set forth in column 2 of the table above).

Irrevocable proxy

The high-vote stockholders deliver an irrevocable proxy to members of the dual-class company’s board to vote in accordance with the recommendation of the company’s board at the stockholder meeting, but the high-vote stockholders do not enter into any binding agreement directly with the counterparty. This would allow the dual-class company to argue that the irrevocable proxy arrangement is carved out from the base transfer restriction by the exemption set forth in column 2 of the table above, although we would note that this interpretation has been challenged in deal litigation.

Other contractual commitments

Conditional conversion or abstention agreement

The high-vote stockholders enter into an agreement with the counterparty whereby, if (a) the stockholder approval would be obtained but for the vote of the high-vote shares against the approval (assuming for this purpose the high-vote shares have been converted into publicly traded shares and voted against the transaction) and (b) the dual-class company’s board has not made an adverse recommendation change in accordance with the transaction agreement, then the high-vote stockholders will either each convert their shares into the publicly traded shares of the dual-class company immediately prior to the stockholder meeting or not attend or vote at the stockholder meeting so long as a quorum will still be established in their absence. [14] The effect of this agreement is that the high-voting stockholders will either be forced to convert their shares or abstain from voting instead of voting against the transaction. A plaintiffs’ firm may still argue that entering into this type of agreement is tantamount to a prohibited “transfer” because the agreement effectively prohibits the high-voting stockholders from voting their high-voting shares against the transaction, but the argument is less compelling because the high-voting stockholder retains flexibility to vote against the transaction with publicly traded shares or abstain.

Vote-down termination fee (i.e., a ’naked no-vote fee’)

The dual-class company agrees in the transaction agreement to pay a termination fee to the counterparty if the approval of the dual-class company’s stockholders is not obtained and the dual-class company’s board has not made an adverse recommendation change in accordance with the transaction agreement.

For dual-class companies on the sell side, this structure is not without risk because, although relevant case law is sparse, M&A practitioners have historically viewed the use of such “naked no-vote” fees in a sale context as potentially constituting impermissible deal protection provisions under Unocal/Unitrin, as they are inherently coercive to the company’s stockholders. As a result, when included in transaction agreements, these fees are typically fashioned as “expense reimbursements” limited to 0.5% to 1.0% of the transaction’s equity value. [15]

On the other hand, there is market precedent in transactions where the dual-class company was the acquirer and an acquirer stockholder vote was required for the acquirer to agree to a significant naked vote-down fee more in line with typical regulatory reverse termination fees, i.e., more than 5% of transaction equity value. [16] This is not surprising, as relevant Delaware case law evaluates the permissibility of reverse termination fees tied to an acquirer stockholder vote based on the fee’s percentage of the acquirer’s equity value, which is higher than the transaction equity value.

One could argue that, regardless of whether the dual-class company is the buyer or seller, if the high-vote stockholders control a majority of the voting power, a significant no-vote termination fee that is only triggered if the transaction is voted down by the high-vote stockholders in circumstances where the company’s board continues to recommend the transaction is not coercive in manner that would run afoul of Unocal/Unitrin, because:

- The company’s public stockholders cannot actually influence the outcome of the vote regardless of whether there is a reverse termination fee.

- The high-vote stockholders are capable of evaluating the merits of the transaction prior to signing the transaction agreement.

- Whether or not the fee is triggered is entirely within the control of the high-vote stockholders.

- The board would remain free to change its recommendation and terminate the transaction agreement to accept a superior proposal if one were to arise.

Nonbinding approaches

Public nonbinding commitment

The high-vote stockholders publicly state in the transaction announcement press release and Form 8-K that they will vote their shares in accordance with the recommendation of the dual-class company’s board. [17]

Private nonbinding commitment

The high-vote stockholders privately assure the counterparty that they intend to vote their shares in accordance with the recommendation of the dual-class company’s board but make no public statement to that effect.

Conclusions

More and more dual-class companies are including explicit carve outs in their charters to permit high-vote stockholders to deliver voting agreements in connection with M&A transactions. We recommend that all pre-IPO dual-class companies include voting agreement carve outs in their charters upon consummation of their IPOs, and that dual-class companies with phase 1 transfer provisions consider adopting “clear day” amendments to their charters to include these carve outs.

Endnotes

1This post mainly focuses on venture capital-backed dual-class companies. Dual-class companies that emerged in other contexts (e.g., portfolio companies of private equity firms that go public with the private equity firm retaining a significant stake or spinoffs from legacy conglomerates) often do not have comparable transfer restrictions in their charters.(go back)

2When we refer to “voting agreement(s)” in this post, we refer broadly to voting and support agreements, support agreements, tender agreements and similar definitive agreements entered into in connection with M&A transactions between a stockholder of the company subject to the stockholder vote and the counterparty to the transaction.(go back)

3 Any M&A transaction involving the stockholder vote of a public company can trigger the issues discussed in this post, including M&A transactions involving an acquirer stockholder vote (which arises most commonly in a parent-to-parent merger or stock transaction involving the issuance of more than 20% of the acquirer’s pre-transaction total shares outstanding).(go back)

4Our review consisted of priced IPOs of Delaware-incorporated companies in the technology sector that were initially filed between January 1, 2020, and January 1, 2022, excluding special purpose acquisition companies, as reported by Deal Point Data.(go back)

5See, e.g., DGCL 251 (setting forth stockholder approval requirements for the merger of a Delaware corporation) and 271 (setting forth stockholder approval requirements for the sale of all or substantially all of the assets of a Delaware corporation). In transactions effectuated by tender offer, holders of the requisite majority tendering their shares into the offer generally will satisfy the stockholder approval requirement under applicable law.(go back)

6Subject to the parameters imposed by the deal protection provisions of the transaction agreement, the fiduciary duties of the selling company’s board of directors require the board to consider bona fide topping bids to an announced transaction and, in certain circumstances, seek to terminate the existing transaction and enter into a transaction with the interloping bidder.(go back)

7These stockholders are almost always limited to active stockholders who report their shareholdings on Schedule 13D (or would so report if they met the relevant ownership thresholds). Passive stockholders who report their shareholdings on Schedule 13G, such as the major index providers Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street, do not provide voting agreements.(go back)

8One of the most contested points of negotiation in a voting agreement is whether the signatories will be required to vote their shares in favor of the transaction even if the board changes its recommendation. While a discussion of these fallaway provisions is outside the scope of this post, boards of directors of target companies must carefully consider whether agreeing to permit the voting agreements to remain in effect even following a change in recommendation constitutes an impermissible deal protection device under Unitrin/Omnicare, taking into account the totality of the other deal protection devices in the transaction.(go back)

9In circumstances where an acquirer stockholder vote is required (e.g., a parent-to-parent merger or a stock transaction where a vote is required under stock exchange rules because the acquirer is issuing more than 20% of its outstanding shares), the transaction agreement likewise will contain a closing condition for obtaining the requisite approval and deal protection provisions in favor of the target company. If the acquirer has significant insider stockholders, the target company will typically require voting agreements from those stockholders as well.(go back)

10See, e.g., Clara Hochleitner, “The Non-Transferability of Super Voting Power: Analyzing the ‘Conversion Feature’ in Dual-Class Technology Firms,” 2018 Drexel Law Review, Vol. 11, 101-147, available at https://drexel.edu/~/media/Files/law/law%20review/v11-1/Hochleitner%20101%20147.ashx.(go back)

11For dual-class companies that completed their IPOs in 2016, practice varied on whether an express voting agreement carve out was included.(go back)

12These charters typically also include a carve out similar to the one in column 2.(go back)

13Charter amendments typically require the approval of the holders of a majority of the voting power of the company’s outstanding stock (although some companies have supermajority voting standards for charter amendments), and amendments involving the terms of the high-voting shares may require separate class votes. Companies should consider the likely reaction of the proxy advisers and their stockholder base before submitting a charter amendment to a stockholder vote.(go back)

14A similar structure was used in Salesforce’s acquisition of Tableau Software, which was announced on June 10, 2019.(go back)

15For example, Alphabet’s acquisition of Fitbit, a dual-class company where the Class B stockholders held more than 50% of the voting power, provided for a termination fee payable by Fitbit equal to 1% of transaction equity value in the event of a vote down by Fitbit’s stockholders. The proxy statement for the transaction also noted that “although they are not obligated to do so,” Fitbit’s high-vote stockholders had informed Fitbit of their intent to vote all of their shares in favor of the proposals presented at the stockholder meeting to approve the transaction.(go back)

16For example, Zillow’s acquisition of Trulia, which was announced on July 28, 2014, provided for a naked no-vote fee payable by Zillow equal to 5.8% of transaction equity value, and Twilio’s acquisition of SendGrid, announced October 15, 2018, provided for a vote-down fee of 7.0% of transaction equity value if Twilio’s Class B stockholders voted against the transaction and the Twilio stockholder approval was not obtained.(go back)

17This approach was used by LinkedIn, a dual-class company, in its acquisition by Microsoft (announced on June 13, 2016). Reid Hoffman, LinkedIn’s founder and controlling stockholder, was quoted in the announcement press release as stating that “I fully support this transaction and the [LinkedIn] Board’s decision to pursue it, and will vote my shares in accordance with their recommendation on it.” Fitbit used a watered-down version of this approach in its acquisition by Alphabet: The proxy statement for the transaction noted that “although they are not obligated to do so,” Fitbit’s high-vote stockholders had informed Fitbit of their intent to vote all of their shares in favor of the proposals presented at the stockholder meeting to approve the transaction.(go back)

Print

Print