Ali Saribas is a Partner, Marianne Mitchell, and Anais Sachiko Gaiffe are Analysts at SquareWell Partners. This post is based on their SquareWell memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes How Much Do Investors Care about Social Responsibility? (discussed on the Forum here) by Scott Hirst, Kobi Kastiel, and Tamar Kricheli-Katz; The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, and Roberto Tallarita; Does Enlightened Shareholder Value add Value (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita; Companies Should Maximize Shareholder Welfare Not Market Value (discussed on the Forum here) by Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales; and Exit vs. Voice (discussed on the Forum here) by Eleonora Broccardo, Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales.

The Playing Field

Each year, SquareWell Partners (“SquareWell”) publishes a study – The Playing Field – reviewing how 50 of the world’s largest asset managers (“Top 50”) are factoring governance and sustainability considerations within their investment decision-making processes and their approach to stewarding portfolio companies. This year’s study demonstrates that investors may have reached the saturation point of visible governance and sustainability integration (becoming a signatory to UN PRI, and establishing a responsible investment team, for example), giving the foundation for practical considerations on these topics for stewardship activities, and progress on how investors think about integration.

I. The Foundations Have Been Laid

Global asset managers have sought out many ways of establishing themselves as responsible investors, becoming signatories to the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investing (“UN PRI”, as well as other initiatives), and establishing the internal structures needed to manage the requirements of being modern stewards of capital. As of July 2022, unchanged from our 2021 study, all but one of the world’s Top 50 asset managers were signatories to the UN PRI. 48 have also now formed a dedicated responsible investment team (up from 46 the previous year, Figure 1), and 49 have established dedicated stewardship teams (up from 45 the previous year) to oversee engagement with portfolio companies’ governance and sustainability activities and instruct proxy voting decisions (Figure 2).

Asset managers have also adapted their offerings to include products such as thematic investments. These investments, offering clients focus on specific sustainability issues, have been adopted by 48 of the 50 top asset managers surveyed. Notably, we see that certain aspects of investors’ approaches to responsible investment, such as developing internal capability and offering innovative products, have become an expectation of large asset managers, rather than a differentiator.

II. Seeking Differentiation

With these new expectations in mind, asset managers are now seeking opportunities for differentiation through other means. Our study of the Top 50 Asset Managers, has shown that three areas of differentiation have emerged:

- How to Leverage External Inputs

- Whether to Vocalize Discontent and Support

- How to Communicate their Agenda

II.a. Leveraging External Inputs

ESG Ratings & Data: One aspect that we see considerable divergence of approaches from asset managers is on the use of ESG ratings and data. The quality and availability of these inputs has never been more important, and the ways in which investors use such ratings, and the underlying data, has become increasingly complex, whether it be in the integration into investment decision-making processes, thematic investing, negative screening, or informing engagement.

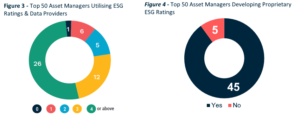

Of the Top 50 asset managers, over half of managers use at least four ESG ratings and data providers, with only one manager not disclosing whether they use one (Figure 3). Asset managers are also reducing their reliance on third party providers by designing proprietary ratings and tools, leveraging multiple sources of external data and research (Figure 4). This personalization shows willingness from asset managers to move away from a standardized industry approach.

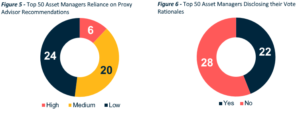

Proxy Advisors: While most asset managers receive recommendations from the two global Proxy Advisors – Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) and Glass, Lewis & Co. (“Glass Lewis”) – most of the Top 50 asset managers have their own internal voting policies. SquareWell’s review finds that a significant number (24) of the Top 50 asset managers now exhibit a “Low” reliance on proxy advisor recommendations (Figure 5). As evidence to the “Low” reliance on the recommendations of proxy advisors, in a 2018 letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), ISS’s CEO stated that 85 percent of ISS’s top 100 clients used a custom proxy voting policy – meaning that they did not rely on ISS’s standard research recommendations but have ISS’s custom research team apply investors’ own voting policies.

22 of the Top 50 asset managers publicly disclose their vote rationales (Figure 6) which now provides a “window” into investors’ evaluation key items coming to a vote. For example, in May 2022, Aviva Investors expressed their concern that Lloyds Banking Group’s emissions reductions targets were not validated by the Science Based Targets Initiative by voting against its Chair, Robin Budenberg, despite both Proxy Advisors recommending in favor of his re-election. Vanguard and BlackRock also publish detailed insights into their voting and engagement in high profile situations – BlackRock, through Vote Bulletins.

II.b. Vocalizing Discontent and Support

Across a number of markets, SquareWell is seeing the definition of “activist” being blurred. “Active Stewards”, a group including both active and passive investors who are more engaged in stewardship, are seeing tactics typically employed by activists to be a useful method achieving change.

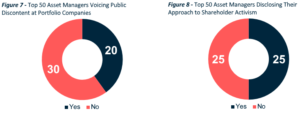

As of 2022, 20 of the Top 50 asset managers had registered public discontent against portfolio companies (Figure 7), demonstrating an increased comfort level by traditional asset managers to vocalize their concerns with portfolio companies. In May 2021, for example, Amundi Asset Management and Nordea Asset Management publicly requested Deutsche Bank to expand its coal policy. Further to this, M&A situations, notably across Europe, have lured asset managers to becoming more vocal, expressing their oppositon to offers that undervalue a portfolio company.

More broadly speaking, supporting activism has become increasingly more accepted by asset managers and perceived as a useful market force. To this end, 25 of the top 50 asset managers include their approach to evaluating contested situations within their public documents, with contested board elections being the most common area they clarify their position (Figure 8). Whilst engaged investors continue to be vocal on issues aligned to long-term shareholder interests, asset managers being open to these rationale and demands will help them to progress their sustainable investment agendas, and provide differentiation compared to those that are less receptive.

Besides situation-related instances of becoming vocal, the number of asset managers that name the companies that they engage with is 32, up from 13 in 2019 (Figure 9). With asset managers increasing both in engagement disclosure and naming companies engaged, there is an ebbing tide on companies that think they can hide from the limelight of unfavorable engagements.

II.c. Communicating the Agenda on Governance and Sustainability

Investors are increasingly vocalizing their expectations on governance and sustainability issues through dedicated position papers. 35 of the top 50 asset managers have published position papers on environmental and social topics, up from 24 in 2019. On governance, while position papers are common, asset managers have taken to publishing regional guidelines. The Vanguard Group, for example, publishes seven regional voting guidelines.

SquareWell has selected below a snapshot of the different topics investors publish on to give an idea of what’s available to companies in terms of guidance from asset managers on key environmental and social topics.

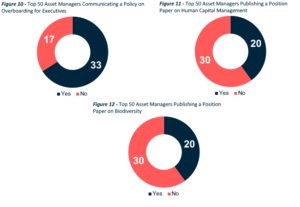

- Governance: Asset managers are increasingly interested in ensuring that directors dedicate sufficient time to their board duties. In addition to having limits on the number of seats non-executive directors should have on public boards, asset managers are increasingly applying stricter policies on the external commitments of company executives. To this end, SquareWell notes that 33 of the Top 50 asset managers outline their expectations of the number of mandates an executive may hold, half of those notably allowing only one outside directorship (Figure 10).

- Social: 20 of the Top 50 asset managers have written about human capital management, up from 16 in 2020 (Figure 11). This increase is likely due to the importance of human capital management through the pandemic, alongside continued social tensions and increased awareness of inequalities within the workplace and society as a whole.

- Environment: Biodiversity has become a growing concern for investors evidenced by 20 of the Top 50 asset managers publishing a position paper on the topic (Figure 12). This interest in the topic has also paved the way to the launch of the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), with 19 of the Top 50 asset managers supporting such initiative. The TNFD aims to develop and deliver a risk management and disclosure framework for organizations to report and act on evolving nature-related risks, and support a shift in global financial flows towards nature-positive outcomes.

III. Concluding Thoughts

In its 2022 client memo published earlier this year – “Reframing ESG” – SquareWell looked to re-frame the term Environmental, Social, and Governance (“ESG”). The term “ESG” has unintentionally led market players to treat “Environmental”, “Social” and “Governance” issues on an equal footing and the current organization of the acronym often leads to the two megatrend “Environmental” and “Social” topics overshadowing “Governance”. As the market matures to evaluating companies based on how “Environmental” and “Social” factors are integrated into corporate strategy, we view a similar maturity developing in the separation of “Governance” from the “ESG” acronym.

“Governance” is a structural property of a company, and the foundation to set a company’s purpose, strategic direction, ability to perform, and most importantly, uphold its ultimate responsibility, to be accountable. Strong governance, creating accountability of companies not only for financial returns but other broader impacts, should act as an enabler for stakeholder considerations in the pursuit of value creation. “Governance” should be viewed as the means of facing environmental and social risks and opportunities, not as an isolated element from this effort. One should not forget that the first recommendation of the Task Force for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”) requests that companies disclose their governance structure around climate-related risks and opportunities.

It is investors responsibility, as active stewards, to monitor boards effectively and encourage the proliferation of features of good governance. One effective mechanism with which this can be engineered, yet is not being used to its full advantage, is holding board members accountable. Year-over-year average investor support for directors remain statistically unchanged, meaning there is significant scope for investors to register their discontent and concern relating to management of “Environmental” and “Social” factors and value creation by choosing who should represent their interests on the boards of their portfolio companies.

Fundamentally, if investors encourage the advancement of good governance principles within portfolio companies, whether through meaningful engagement or voting activities, “Environmental” and “Social” expectations are more likely to be met, and subsequently there will be less room for scrutiny on asset managers regarding these issues. In that sense, if the term “ESG” is to be understood literally, it should perhaps be organized vertically, with the “G” forming the foundation with which the “E&S” lay upon.

Print

Print