Tina Shah Paikeday is the Global Head of the Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Practice, and Nisa Qosja is a Knowledge Consultant at Russell Reynolds Associates. This post is based on their Russell Reynolds memorandum. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Politics and Gender in the Executive Suite (discussed on the Forum here) by Alma Cohen, Moshe Hazan, and David Weiss; Will Nasdaq’s Diversity Rules Harm Investors? (discussed on the Forum here) by Jesse M. Fried; and Duty and Diversity (discussed on the Forum here) by Chris Brummer, and Leo E. Strine, Jr.

What is the state of diversity in the C-suite?

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion have been climbing the board and CEO agendas for decades. But while we’ve seen strong commitments and progress in entry-level roles across industries, we’re still a long way off from achieving true equity at the top.

So, what’s holding leaders back? And how can organizations finally make progress for the good of the business, society, and global economies?

To understand the state of C-suite diversity in America, and find ways to create truly representative leadership, we analyzed 1,583 executives at the 100 largest companies in the S&P500—what we call the S&P100.

The headline finding is that organizations still have a lot of work to do to ensure C-suite equity.

- C-suites in Corporate America are still disproportionately white and male. We see severe under-representation of women, Black, and Hispanic/Latino executives in most C-suite positions.

- Asian leaders experience a 25% representation decline from P&L leadership to the CEO role whereas Whites experience a 10% increase from P&L leadership to the CEO role.

- The lack of equity at the top isn’t due to a pipeline problem. The US workforce is diverse. Yet a lack of equity in assessing, developing, and promoting talent is undermining representation at the C-suite level.

- Addressing top team imbalances requires revolution, not evolution. Without concerted effort, diversity imbalances will continue and grow as underrepresented groups don’t see role models they can aspire to be.

In this paper, we explore how succession planning can help plug diversity gaps at the executive level. We share detailed insights into the current C-suite composition, and detail five ways boards and corporate leaders can develop a diverse and sustainable pipeline of C-suite leaders.

Diversity snapshot

SOURCE: RRA Proprietary Analysis, S&P100 Leadership Teams, 2022 (n=100 companies, 1583 executives); Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021 “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity”, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race and therefore are also included in the racial categories.

C-suite equity is a distant goal

The American workforce is diverse, with 37% being Asian, Black, or Hispanic/ Latino, and 47% being women. This creates a melting pot of skills, ideas, and experiences that helps organizations innovate and thrive. Yet that diversity isn’t flowing into executive leadership.

When we looked at the 95 S&P100 C-suites with more than seven executives, we found a considerable proportion lacked meaningful diversity.

Source: RRA Proprietary Analysis, S&P100 Leadership Teams, 2022 (n=100 companies, 1583 executives); Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021 “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity”, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htmhttps://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race and therefore are also included in the racial categories.

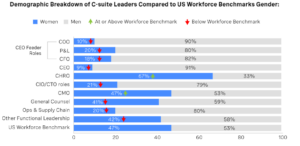

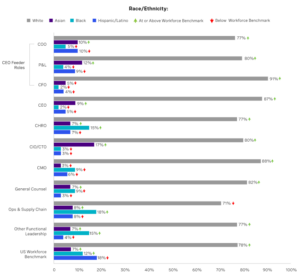

Diversity deep dive across C-suite roles

When we analyzed diversity within individual C-suite roles, we found a serious underrepresentation of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and women executives in the seats that wield the most power and influence on an organization. This includes the COO and CFO roles, as well as P&L leadership positions, which typically have greater exposure to the board and are often go-to targets in CEO succession plans.

Instead, we see underrepresented groups cluster in functional roles that usually aren’t steps on the road to CEO roles. For example, Black executives see the most representation in supply chain roles, while women only see proportionate representation in the CHRO seat. Hispanic/Latino executives fare worst overall, facing severe underrepresentation across every C-suite role.

The case for Asian leaders is particularly interesting and warrants further analysis. Although Asian leaders exceed their workforce benchmark representation in P&L leader roles (12%), this representation drops at the CEO level (9%). In contract, white leaders representation continues to increase beyond workforce benchmarks of 78%, to 80% in P&L roles, and 88% in CEO roles. Part of the explanation for why Asian leaders may experience a drop at CEO, is due to the narrow and limiting biases around ‘good leadership’ which ultimately hinders Asian leader progression.

Source: RRA Proprietary Analysis, S&P100 Leadership Teams, 2022 (n=100 companies, 1583 executives); Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021 “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity”, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race and therefore are also included in the racial categories.

Source: RRA Proprietary Analysis, S&P100 Leadership Teams, 2022 (n=100 companies, 1583 executives); Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021 “Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity”, https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.htm Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of any race and therefore are also included in the racial categories.

Bias is holding back diversity

Our analysis shows the lack of equity at the top of organizations isn’t due to a lack of diverse talent entering the workforce. It’s due to a lack of equity in assessing, developing, and promoting talent.

Source: Divides and Dividends: Leadership actions for a more sustainable future.

It will take large-scale change, not just incremental improvement, to correct the C-suite diversity imbalance in Corporate America. And the consequences of inaction are far-ranging, with the potential to undermine long-term performance and competitiveness.

- A lack of diverse role models who can inspire others creates recruitment and retention challenges. At the same time, bias in the assessment and development of underrepresented groups limits the progression opportunities for high-potential talent.

- With too few Black, Hispanic/Latino, and women leaders in the COO, CFO, and P&L leadership roles—which are often steppingstones to the CEO seat— succession pipelines become homogenous and less robust.

- A lack of diverse leaders’ fuels board recycling rates—where the same people sit on multiple boards—which undermines business differentiation. While this is starting to decline as organizations increasingly look for board members with supply chain, marketing, and tech expertise, it will remain a problem until we see true representation at the top level.

Five ways to diversify leadership pipelines

Simply hiring more diverse talent won’t solve the diversity imbalance at the top. Instead, organizations need to build equitable internal talent pipelines that fuel successive leadership plans at every level.

To do this, the board, CEO, and C-suite should embed five equitable succession practices into their planning:

1. Build a forensic understanding of your internal pipeline

Knowing where to start requires a better understanding of where diverse talent sits within your organization, and at what level they begin to struggle to progress. By tracking demographics such as gender, race, and ethnicity, HR can work with senior leaders to spot and address diversity gaps in leadership pipelines before they become entrenched

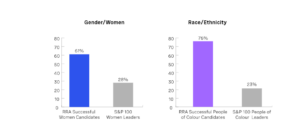

Doing this leads to measurable results on diversity. Data from our executive searches shows that both gender and racial diversity are high when we track the diversity of our candidate pools.

Source: RRA analysis of Successful Candidate data for DEI prioritized search assignments. N= 696. DEI prioritized assignments are identified as assignments where a client has a criteria around diversity, RRA employed equitable search practices in these cases. Data is as of July 2022. People of color includes: Black/African/Caribbean, Hispanic/Latino, Asian and Multiracial.

2. Assess potential, not just experience

Once you know where your diverse talent sits, and at what leadership levels hurdles appear, you can look to take bias out of assessing talent. By using data-backed psychometrics, competency interviews, and 360 feedback to assess potential, you can look beyond experience in select roles to identify the behaviors and capabilities that underpin future success.

This is especially important as our analysis of the S&P100 shows Black, Hispanic/Latino, and women leaders have less opportunity to demonstrate their performance in business-critical areas. And, even when they have time in the right roles, our survey of Black leaders in the technology industry revealed they don’t get the same opportunities. Among Black and non-Black leaders with a similar number of years of experience, only 61% of Black professionals said they had led major company initiatives, compared to 88% of non-black professionals.

While assessing potential is key to overcoming the established imbalance in experience, it is also essential to finding the best leads for our dynamic world. As priorities and requirements are always evolving, you need leaders with the potential to find novel solutions, rather than the ability to use what has worked in the past.

3. Supercharge development for emerging leaders

After identifying high-potential leaders, it’s important to develop them in the right way. HR and L&D teams should create development programs that focus on building business exposure and experience. Marrying early assessment of potential with business-focused development can help level the playing field for underrepresented groups who currently don’t get exposure to the experiences that grant entry to the C-suite and, often, the board.

4. Be intentional about C-suite sponsorship programs

Despite sponsors playing a big part in supporting the career advancement of underrepresented talent, sponsorship isn’t happening at the rate it should. Setting more formal expectations for C-suite sponsors and an intentional pairing process will help.

Education and training for sponsors can help them connect deeply with those who don’t share their background by showing them how to practice courage, vulnerability, and curiosity. And the benefits of inclusive sponsorship go beyond the underrepresented leaders. The sponsors also gain personally and professionally by showing their commitment to investing in their organization’s future leaders.

5. Double down on overcoming unconscious bias

Don’t ignore bias in talent processes. Unconscious bias training in recruitment has become common, and succession planning needs to follow suit.

Educating leaders on common biases in the talent identification and succession process, whilst equipping them with strategies to minimize the impact of bias, can help transform the composition of the pipeline and generate better parity across roles in the short- and long-term.

How we build diverse C-suites

The lack of C-suite diversity in the S&P100 is in no way intentional—we’ve seen strong commitments to equity across industries for more than two decades. The commitment is there, but leaders are struggling to deliver effective results. That’s no surprise when we’re looking to overcome unconscious bias and change talent progression systems that have only slowly evolved over the last 100 years.

Yet, we must accelerate the path to parity. The fundamental rethink of progression processes required to build a sustainable diverse C-suite often takes an independent view. That’s why we work at the individual, team, and organizational levels to shift attitudes, behaviors, practices, and processes. Merging this approach with robust data, we help you optimize effectiveness and show progress over time.

Methodology

We analyzed the 1,585 executives sitting on the leadership teams of the 100 largest companies in the S&P500—what we called the S&P100. We defined the leadership team using data from the people intelligence firm Boardex and the company’s website.

We pulled gender data directly from Boardex and used standard race and ethnicity data from the US census to design a manual mapping process that showed the race and ethnicity of the 1,583 leaders. We employed a set of evidence-based criteria to qualify and map a leader’s identity and made thorough quality checks before analyzing the data.

Due to the complexity and sensitivity of this data, we only report numbers in aggregate and never share individual-level data or specific company data.

Print

Print