Roni Michaely is a Professor of Finance and Entrepreneurship at The University of Hong Kong, Silvina Rubio is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Bristol, and Irene Yi is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the University of Toronto. This post is based on their recent paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, Scott Hirst; Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance: Theory, Evidence and Policy (discussed on the Forum here) and The Specter of the Giant Three (discussed on the Forum here) both by Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst.

Voting is a central part of corporate governance, giving shareholders the power to shape a company’s future. With institutional investors holding more than 70% of publicly traded companies’ shares in the US, the success of governance hinges on institutional investors responsibly using their voting power. But what drives institutional investors’ voting decisions? While existing literature has shed some light on the factors influencing institutional investors’ voting decisions, the specific reasons behind each vote often remain elusive. Researchers typically infer these reasons from observable information such as voting patterns and the characteristics of companies, sponsors, proposals, or institutional investors. However, without an explicit rationale accompanying each vote, it is challenging to uncover the reasons that guide their voting decisions.

In our study titled Voting Rationales, we study why institutional investors vote the way they vote on director elections and the impact on firm’s actions, by examining a novel dataset containing 611,389 institutional investors’ voting rationales. Voting rationales are vote-specific, voluntarily disclosed, and have the potential to reveal valuable information beyond what is contained in votes alone. Examples include “A vote AGAINST incumbent Nominating Committee member William (Bill) Larsson is warranted for lack of diversity on the board” or “Adopted or renewed poison pill w/o shareholder approval in past year.” While voluntary, disclosing voting rationales is encouraged by the United Nations (UN) Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), and we find that it has become increasingly popular in recent years. During the 2021 proxy season, 5.4% of all votes and 15.3% of votes against directors had a rationale. In our sample, spanning from 2014 to 2021 proxy seasons, 83% of proposals on director elections and 90% of meetings have at least one rationale. Our data cover a broad range of meetings, providing insight into institutional investors’ concerns when casting their shares.

To better understand why institutional investors vote the way they do on director elections, we systematically classify 611,389 voting rationales in our sample into 15 distinct categories using a deep learning-based language model called Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model. Our analyses reveal several important findings, and we highlight several of them here.

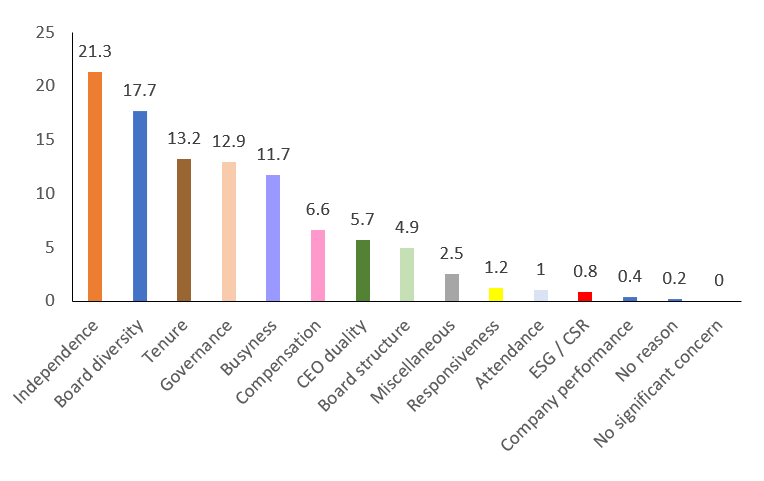

First, we quantify the relative importance of each reason. Our analysis shows that director independence and board diversity are the main reasons for voting against directors. In Figure 1, we present the importance of each rationale on votes against directors, focusing on votes against because rationales for votes in favor are uncommon and typically uninformative. Our analysis reveals that independence is the most important reason, accounting for 21% of rationales and mentioned in 67% of meetings, while board diversity is the second most common reason, constituting 18% of rationales and mentioned in 72% of meetings. This concern was frequently mentioned even before the Big Three institutional investors (i.e., BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street) launched campaigns to promote gender diversity in 2017. We also find that a small, but growing fraction of institutional investors holds director nominees responsible for concerns over ESG/CSR, especially after the 2019 proxy season.

Importantly, we observe that voting rationales do not just mirror those of proxy advisors. For example, some of the most common voting rationales like director tenure and board diversity do not appear to be important considerations for proxy advisors. We also find substantial heterogeneity in voting rationales across institutional investors. For instance, board diversity is more frequently mentioned by US investors compared to European ones, and by UN PRI signatories compared to non-signatories.

Figure 1. Relative importance of each rationale on votes against directors (2014-2021)

Second, in the aggregate, voting rationales provide an accurate picture of a company’s governance weaknesses. We find that companies receiving a higher proportion of rationales related to board diversity have less gender-diverse boards, with the proportion of rationales indicating the relative importance of each issue. We also observe the same pattern for companies with long director tenure and busy directors. Importantly, these results indicate that institutional investors cast informed votes, despite recent concerns about their lack of incentives to exert sufficient governance. While rationale-washing (i.e., the practice of misrepresenting voting rationales to project a particular narrative or image), conflicts of interest, or motivation to pursue a private interest may prevent institutional investors from disclosing the actual reasons behind their votes, we find a strong correlation between board characteristics and rationales, suggesting the dominance of truthful rationales over misleading ones.

Third, our findings show that directors are willing to address concerns that result in high shareholder dissent. Specifically, companies with high dissent voting related to board diversity increase the percentage of female directors in the following year. Likewise, companies with high dissent voting related to director tenure and busyness reduce the average director tenure and busyness, respectively. Importantly, dissent alone cannot explain changes in board gender diversity, tenure, or busyness, but only when rationales refer to these issues. This suggests that voting rationales are effective tools to communicate the source of this dissent. We further show that our results are not driven by companies inferring the source of dissent from their board characteristics. Our findings support the view that companies address concerns investors state in their voting rationales and voting rationales might be an effective tool for institutional investors seeking to influence corporate policies.

Our research adds a new and relevant dimension to the ongoing discussion about the importance of fund voting and accountability in the voting process. Our results show that companies are responsive to institutional investors’ concerns, indicating that the disclosure of voting rationales can be a powerful, yet cost-effective way to engage with companies and change their governance practices. The UN PRI recommends their signatories to publicly disclose voting rationales, particularly for high-profile or controversial votes. Our results suggest that institutional investors can effectively use voting rationales to communicate with companies, bringing transparency to the decision-making process.

We are willing to take our conclusion a (somewhat speculative) step further and suggest that regulatory authorities around the world may want to consider a mandatory disclosure of rationales, at least for contentious votes. This change will make those institutions more accountable to their own investors, and improve corporate governance and decision making within firms they invest in; all with relatively low cost.

Print

Print