Gregory V. Gooding and Maeve O’Connor are Partners and Caitlin Gibson is a Counsel at Debevoise & Plimpton LLP. This post is based on a Debevoise memorandum by Mr. Gooding, Ms. O’Connor, Ms. Gibson, Andrew Bab, Bill Regner, and Matthew Ryan, and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

This post surveys corporate transactions announced during the first half of 2023 that used special committees to manage conflicts and key Delaware judicial decisions during this period ruling on issues relating to the use of special committees.

Who Controls and When?

Delaware courts have held that transactions between a controlled company and its controller are subject to the test of entire fairness—Delaware’s most exacting standard of review—due to the inherent risk of minority stockholder abuse presented by such transactions. In structuring a transaction between a Delaware company and a significant stockholder—or a transaction in which a significant stockholder has interests that differ from those of other stockholders—the first step is to determine whether that significant stockholder controls the company, either generally or with respect to the specific transaction being considered.

In some cases, the answer is clear. A stockholder owning more than 50% of a company’s voting power controls that company. In the case of a public company, ownership of somewhat less than 50% can result in control given the practical reality that less than 100% of the shares will be present at any stockholder meeting, with the result that the near majority stockholder will be able to elect the entire board. But the controller status of a stockholder owning a significant, but meaningfully less than majority, equity interest occupies a more uncertain status. While Delaware courts have found control potentially to exist at levels well below 50% ownership, proving control in those circumstances requires the plaintiff to demonstrate that the alleged controller has actually dominated the company’s conduct, either generally or with respect to the particular transaction being challenged. The existence of such control is a “highly contextualized” question, depending not only on share ownership but also on a variety of other factors, [1] none of which alone may be sufficient to prove control. Rather, “[a] finding of control . . . typically results when a confluence of multiple sources combines in a fact-specific manner to produce a particular result,” [2] as illustrated by the examples below.

The Delaware Court of Chancery’s decision in In re Zhongpin Inc. Shareholders Litigation [3] involved the take-private of Zhongpin by Xianfu Zhu, a 17.3% stockholder who was the company’s CEO and founder. In submitting his initial acquisition proposal, Zhu made it clear to the company’s board that he was only interested in acting as a buyer and had no interest in selling his shares to a third party. An independent special committee was formed to consider his proposal and to conduct a pre-signing market check. Only one competing offer was received, which, although higher than Zhu’s proposal ($15 per share compared to $13.50 per share), was conditioned on Zhu’s continuing as the company’s CEO, which he refused to do. The special committee ultimately accepted Zhu’s original offer of $13.50 per share, subject to a 60-day post signing go-shop during which no alternative proposals were received. The transaction was negotiated by the special committee and approved by a vote of the disinterested stockholders but that vote was not required at the outset of the deal and thus was not sufficient to shift the standard of review for a controller transaction from entire fairness to business judgment. Accordingly, the controller question was critical. In denying a motion to dismiss breach of fiduciary duty claims against Zhu, the Court of Chancery found it reasonably conceivable that Zhu exercised general control over the company’s day-to-day operations, noting, in particular, that the company’s Form 10-K explicitly stated that Zhu “has significant influence over our management and affairs and could exercise this influence against your best interests.” The court also found that Zhu could—and conceivably did—exercise control over the challenged transaction, evidenced by his unwillingness to sell his own shares and his refusal to continue as CEO.

Similarly, in In re Tesla Motors, Inc. Shareholders Litigation, [4] the Court of Chancery found it reasonably conceivable, at the motion to dismiss stage, that Elon Musk controlled Tesla despite owning only 22.1% of Tesla’s common stock. The challenged transaction involved Tesla’s 2016 acquisition of SolarCity Corporation. At the time of the acquisition, Musk was SolarCity’s largest stockholder and the chairman of its board. In denying a motion to dismiss breach of fiduciary duty claims against Musk, the court noted that while a “close call,” it was “reasonably conceivable that Musk controlled the Tesla Board in connection with the [challenged transaction].” Several well-pled facts factored into the court’s decision, including statements in the company’s SEC filings that Tesla is “highly dependent on the services of Elon Musk,” Musk’s public comments about the company’s need for his management and Musk’s demonstrated willingness to oust members of management who displeased him. Perhaps most importantly, in the court’s view, was the fact that “there were practically no steps taken to separate Musk from the Board’s consideration of the [challenged transaction]” and the failure of the Tesla board to consider forming a special committee notwithstanding the number of directors who were clearly conflicted with respect to the transaction. After trial, the Court of Chancery ultimately decided—without making a definitive determination as to Musk’s status as a controller—that the transaction was entirely fair, a decision which was recently affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court. [5]

In contrast, the Court of Chancery recently found, after trial, that Larry Ellison did not control Oracle, despite his status as the company’s “visionary founder” and his ownership of 28% of Oracle’s common stock. The challenged transaction, described in more detail later in this post, involved Oracle’s 2017 acquisition of NetSuite, a company in which Ellison owned an approximate 40% interest. In failing to find that Ellison had general control over Oracle’s day-to-day operations, the court relied on several specific examples in which either the board or Oracle’s management acted in opposition to Ellison. As to the NetSuite transaction, the court noted that while Ellison “had the potential to influence the transaction,” he did not do so in actuality, evidenced by, among other things, his complete lack of contact with the special committee and recusal from any discussions regarding the transaction. According to the court, “[t]he concept that an individual—without voting control of an entity, who does not generally control the entity, and who absents himself from a conflicted transaction—is subject to entire fairness review as a fiduciary solely because he is a respected figure with a potential to assert influence over directors, is not Delaware law.” Despite the court’s conclusion, it is worth bearing in mind that the claim that Ellison controlled Oracle survived a motion to dismiss, and the court’s ultimate determination that the transaction was not subject to entire fairness review was reached only after a lengthy and undoubtedly expensive trial.

Delaware courts have also conferred controller status on minority stockholders deemed to be working together as a group. To establish a control group, the stockholders must be connected in a “legally significant way—such as by contract, common ownership, agreement or other arrangement—to work together toward a shared goal,” and there must be “more than a mere concurrence of self-interest” among the alleged group members. [6] A legally significant connection can be established through historical or transaction-specific ties between stockholders. For example, in Garfield v. BlackRock Mortgage Ventures, LLC [7], which involved a reorganization of PennyMac, the Court of Chancery found it reasonably conceivable, at the pleading stage, that two significant stockholders who collectively owned 46.1% of the company’s common stock constituted a control group. Historical ties were evidenced by the stockholders’ ten-year history of joint investment in the company, their status as founding partners of the company and their interchangeable reference in transaction documents as “Sponsor Members.” Examining transaction-specific ties, the court noted that management met with the two stockholders together to discuss the reorganization prior to talking to the board, while failing to discuss the reorganization with any other stockholders; that management presentations referred to the two stockholders as a group; and that the reorganization could not be terminated without the consent of both stockholders. In contrast, the Delaware Supreme Court, in Sheldon v. Pinto, declined to find that three venture capital funds constituted a control group despite their participation in a financing that significantly diluted other stockholders. In upholding a motion to dismiss in that case, the court noted that the three VC funds were not the only participants in the financing, that there was no history of coordination among the funds and that each of the three funds retained the right to vote in its discretion on all corporate matters outside of director elections.

Delaware Supreme Court Takes up “MFW Creep”

The Delaware Supreme Court held in Kahn v. M & F Worldwide Corp., 88 A.3d 635 (Del. 2014) (“MFW”) that a controller squeeze-out transaction could be entitled to business judgment review if certain conditions were met—in particular, that the transaction was conditioned ab initio on the approval of a special committee of independent directors and the favorable vote of a majority of unaffiliated stockholders. Since then, transaction planners and lower courts have applied the MFW formula to obtain business judgment rule protection for a wide range of conflicted transactions with controllers, including, for example, decisions related to executive compensation, related party transactions that result in a non-ratable benefit to the controller and agreements with the controller in the context of a third-party merger.

In recent years, some observers have argued that requiring the MFW dual protections to obtain business judgment rule protection in contexts other than a controller squeeze-out—so-called “MFW creep”—is unnecessary, inefficient and inconsistent with Delaware precedent. Instead, the argument goes, any one of three cleansing mechanisms should be sufficient to obtain business judgment review of a conflicted transaction other than a controller squeeze-out: approval by a majority independent board; by an independent special committee; or by a majority of shares held by unaffiliated stockholders.

In May, the Delaware Supreme Court took up the issue of MFW creep in the context of In re Match Group, Inc. Derivative Litigation. The case involves a challenge to Match Group’s 2020 separation from its controlling stockholder, IAC/InterActiveCorp, by means of a reverse spinoff— a transaction that is arguably the opposite of a controller squeeze-out. The transactions effectuating the reverse spin-off were negotiated by a special committee and subject to the MFW conditions. The Court of Chancery dismissed the lawsuit under MFW, finding that the MFW conditions were satisfied, despite a pleading-stage inference that one of three special committee members lacked independence, because the committee had an independent majority, and a majority-of-the-minority vote was obtained. The plaintiffs appealed. After oral argument, the Delaware Supreme Court requested supplemental briefing on the question “whether the Court of Chancery judgment should be affirmed because the Transactions were approved by either of (a) the Separation Committee or (b) a majority of the minority stockholder vote”—in other words, whether satisfaction of only one of the MFW conditions would suffice to invoke the business judgment rule. Although this argument had not been raised below, the Supreme Court stated that resolving the issue “is in the interests of justice to provide certainty to boards and their advisors who look to Delaware law to manage their business affairs” and “will provide certainty to the Court of Chancery, which has continued to address MFW outside the context of controlling stockholder freeze out transactions in a manner that has evaded appellate review.” While the Delaware Supreme Court has not yet ruled on the matter, a decision that provides an easier path to business judgment rule protection would likely to lead to a greater number of related party transactions and, as a result, increased use of special committees.

Recent Special Committee Decisions

A casual sharing of interests between neighbors—including frequent cycling—does not

impair independence.

Orbit/FR was acquired by its controlling stockholder, Microwave Vision, in a transaction approved by a special committee of Orbit independent directors. Following closing, former Orbit stockholders challenged the transaction alleging, among other things, that one member of the special committee (Merrill) lacked independence from Microwave on the basis of his personal relationship with another member of the Orbit board (Iverson). Iverson was a senior executive of both Orbit and Microwave. Merrill and Iverson were friends, neighbors and frequent cycling companions. Iverson was also responsible for Merrill becoming a director of Orbit. The Delaware Court of Chancery held these allegations—“a rather casual sharing of interests between neighbors”—insufficient to call Merrill’s loyalty to Orbit into question. In re Orbit/FR, Inc. Stockholders Litigation, C.A. No. 2018-0340-SG, memo op. (Del. Ch. Jan. 24, 2023).

Business judgment rule applies notwithstanding the ability of a conflicted fiduciary to control the board’s decision, where such control is forborne, and the transaction is negotiated and approved by a well-functioning special committee.

Oracle acquired NetSuite, which was approximately 40% owned by Larry Ellison, the Chairman, founder and 28% stockholder of Oracle, in a transaction approved by a special committee of independent directors of Oracle. Following closing, stockholders of Oracle brought fiduciary duty claims against the directors and certain officers of Oracle, claiming that NetSuite was acquired at an excessive price for the benefit of Ellison. Plaintiffs alleged that Ellison controlled Oracle and its board and that the officer defendants committed a fraud on the board by providing misleading information and failing to disclose certain discussions with NetSuite in connection with the negotiation of the transaction. After trial, the court ruled in favor of the defendants, finding that (i) Ellison did not have voting or operational control of Oracle, (ii) while his position as Oracle’s founder, largest stockholder and “visionary leader” likely would have allowed Ellison to exert control over Oracle’s decision to acquire NetSuite if he so wished, Ellison recused himself from the board’s consideration of the transaction and did not otherwise attempt to exercise control over the board’s decisions relating to the transaction; (iii) the officers of Oracle did not defraud the board, and (iv) as a result, the transaction was subject to business judgment rather than entire fairness review. In so holding, the court noted the robust special committee process, the quality of the committee’s advisors and evidence that the committee vigorously bargained over the terms of the transaction and was willing to walk away from the transaction. In re Oracle Corp. Derivative Litigation, C.A. No. 2017-0337-SG, memo. op. (Del. Ch. May 12, 2023).

In a going-private transaction, the failure to conduct a market check where controller states it is unwilling to sell and relationships of the controller and the advisors to the special committee of the target do not defeat the applicability of MFW.

Brookfield Renewable Partners, the majority stockholder of TerraForm Power, took TerraForm private in a transaction subject to the MFW conditions: namely, the approval of a special committee of independent TerraForm directors and the vote of a majority of the TerraForm shares not owned by Brookfield. Following closing, former stockholders of TerraForm brought breach of fiduciary duty claims against Brookfield and TerraForm’s former directors and officers. Defendants moved to dismiss, asserting that compliance with the MFW conditions rendered the transaction subject to the business judgment rule. The court rejected plaintiffs’ various assertions as to why MFW did not apply, including the failure of the committee to conduct a market check and its hiring of conflicted advisors. In particular, the court held that the decision not to conduct a market check was reasonable in light of Brookfield’s statement that it was not interested in selling its shares or in a third-party sale transaction. As to the advisor conflicts, the court held that, while the financial ties between Brookfield and the special committee’s financial advisor (including investments in other Brookfield entities and the advisor’s concurrent representation of Brookfield in an unrelated transaction) and the conflicts of the committee’s legal counsel (including their previous and concurrent unrelated work for various Brookfield affiliates) were “suboptimal,” those relationships were insufficient to demonstrate a breach of the committee’s duty of care. City of Dearborn Police & Fire Revised Retirement System (Chapter 23), et al. v. Brookfield Asset Management Inc., et al., C.A. No. 2022- 0097-KSJM, tr. ruling (Del. Ch. June 9, 2023).

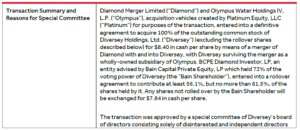

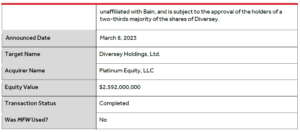

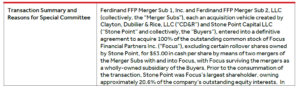

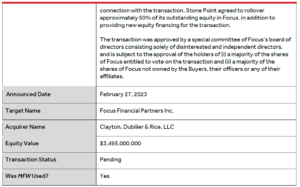

Special Committee Transaction Overview [8]

Endnotes

1In addition to significant stock ownership (but less than a majority), possible indicia of control include: relationships between the alleged controller and particular directors, managers or advisors; the ability to exercise contractual rights to create a particular outcome; the existence of commercial relationships that give the alleged controller leverage over the company (e.g., status as key supplier or customer); and the ability to exercise influence on the board through a high-status position (such as a founder or CEO)—among others. Basho Techs. Holdco B, LLC v. Georgetown Basho Inv’rs, LLC, 2018 WL 3326693 (Del. Ch. July 6, 2018).(go back)

2Basho.(go back)

3C.A. No. 7393-VCN (Del. Ch. Nov. 26, 2014).(go back)

4In re Tesla Motors, Inc. S’holder Litig., 2018 WL 1560293 (Del. Ch. Mar. 28, 2018).(go back)

5In re Tesla Motors, Inc. S’holder Litig., No. 181, 2022 (Del. June 6, 2023).(go back)

6Sheldon v. Pinto, A.3d, 2019 WL 2892348 (Del. Oct. 4, 2019) (collecting cases interpreting

Dubroff v. Wren Hldgs., LLC, 2009 WL 1478697 (Del. Ch. May 22, 2009)).(go back)

7C.A. No. 2018-0917-KSJM (Del. Ch. Dec. 20, 2019).(go back)

8This Special Committee Transaction Overview does not include certain transactions with

an equity value of less than $500 million.(go back)

Print

Print