Since 2021, Ropes & Gray has been actively tracking the various approaches states have taken on how or whether environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors should be applied to the investment decisions for public retirement systems. States have used legislative, administrative and enforcement mechanisms to address this area, which has been complemented by Congressional Republicans’ various attempts to shine a spotlight on ESG in recent months. Judging by the significant uptick in activity this year at both the state and federal levels, the fight over ESG in public investments is far from over and may even be just beginning.

This white paper seeks to provide context for understanding what has happened in the states in 2023 along with considerations that asset managers should be mindful of when engaging with public retirement plans. In the first part of this paper, we provide an overview of current trends in state ESG legislation and regulation along with background for how we got to this point. In the second part, we provide a recap of what has transpired in each state along with an assessment of the state’s policymaking regarding ESG and public pension investments.

Part I: Overview of How We Got Here and Current State ESG Trends

Early State ESG Actions

As a result of the ongoing debate over what role ESG considerations should play in investment decision-making, there has been a growing substantive divergence between how public pensions and private sector retirement plans subject to ERISA are regulated. While those who manage the assets of governmental plans are subject to the fiduciary and other legal requirements of applicable state law, most states’ standards have historically mirrored the fiduciary responsibilities and requirements under ERISA, often using the same terminology and principles, such as the duties of prudence and loyalty. Moreover, for many years, in the absence of guidance at the state level, investment professionals have construed the rules that govern public plans by applying the same interpretations that the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) had issued under ERISA.

We now find ourselves in a new world where many state governments have started articulating their own standards of what it means to be a fiduciary overseeing public pension money, especially when it comes to ESG matters. Initially, this effort to flesh out state pension fiduciary duties in terms of ESG considerations came from a few blue states in the late 2010s.

For example:

- Connecticut – In January 2015, a bill was introduced in the Connecticut General Assembly (HB 5733) that directed the Treasurer to encourage fossil fuel companies in which state funds were invested to take actions to reduce environmental harm and preserve the sustainability of such companies and to divest (or to decide not to further invest state funds or enter into any future investment in any fossil fuel company) if the Treasurer had determined that such action was necessary and warranted. Additionally, in December 2019, after numerous attempts to engage with civilian firearms manufacturers around reforms that could be made in the wake of the Sandy Hook school massacre, the Connecticut Treasurer at that time announced his decision to divest from these companies as part of a first-of-its-kind comprehensive policy framework known as the “Responsible Gun Policy”, which was designed to mitigate the risks associated with gun violence.

- Illinois – Also in 2019, spearheaded by the Illinois Treasurer, the legislature passed the landmark law, “The Sustainable Investing Act” (PA 101-473), which provides that all state and local government entities Since 2021, Ropes & Gray has been actively tracking the various approaches states have taken on how or whether environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors should be applied to the investment decisions for public retirement systems. States have used legislative, administrative and enforcement mechanisms to address this area, which has been complemented by Congressional Republicans’ various attempts to shine a spotlight on ESG in recent months. Judging by the significant uptick in activity this year at both the state and federal levels, the fight over ESG in public investments is far from over and may even be just beginning. This white paper seeks to provide context for understanding what has happened in the states in 2023 along with considerations that asset managers should be mindful of when engaging with public retirement plans. In the first part of this paper, we provide an overview of current trends in state ESG legislation and regulation along with background for how we got to this point. In the second part, we provide a recap of what has transpired in each state along with an assessment of the state’s policymaking regarding ESG and public pension investments. AS OF NOVEMBER 3, 2023 2 LAST UPDATED – 9/13/22 136809818_13 ROPESGRAY.COM that hold and manage public funds should integrate materially relevant sustainability factors into their policies, processes and investment decision-making. According to the Treasurer, sustainability factors can have a material impact on business performance and long-term shareholder value, and investors have an interest in integrating these factors into investment decision-making processes.

- Maine – In June 2021, Maine became the first state in the U.S. to enact legislation that requires the board overseeing the state public retirement system to divest the plan’s holdings of the 200 largest publicly traded fossil fuel companies in the world, which must be complete by January 1, 2026.

In the last two years, we have seen a shift—the number of actions from the red states addressing ESG in the public pension context has significantly increased. The recent surge can be attributed in part to both blue state activity and the backlash the Biden administration generated from its May 2021 directive to the DOL to identify steps the agency could take to protect the life savings and pensions of U.S. workers and their families from the threats of climate-related financial risk. President Biden’s executive order culminated in the 2022 socalled “ESG rule”, which revisited fiduciary standards under ERISA regarding investment selection as well as exercises of shareholder rights, and the role that ESG factors can play in those processes. The DOL’s 2022 ESG rule clarifies that climate change and other ESG factors may be relevant to the risk and return analysis of a potential investment, and when they are relevant, they may be weighted and factored into investment decisions alongside other relevant factors as deemed appropriate by fiduciaries. The DOL’s 2022 ESG rule does not require or suggest that plan fiduciaries must or should consider ESG factors when investing plan assets.

The Red States’ Backlash

The core of the DOL’s 2022 ESG rule—the neutrality of approach to ESG factors and the need to focus on relevant riskreturn factors and not subordinate the interests of participants and beneficiaries to objectives unrelated to the provision of benefits under the plan—are in line with established DOL principles. However, elected officials in many red states have described this rule as a mandate that ESG factors must be part of a plan fiduciary’s investment process. Consequently, politicians in these red states have aggressively pursued through legislation and administrative fiat (i) prohibitions on the ability to consider ESG factors to the extent they are found to be “non-pecuniary” (as described below) as well as (ii) restrictions on the ability to invest with financial institutions that allegedly boycott certain industries such as fossil fuel and firearms.

Anti-ESG Laws Imposing Limits on Investment Considerations and Fiduciary Discretion

With anti-ESG initiatives, lawmakers seek to impose new requirements and conditions on the ability to act as a fiduciary to state pension plans by requiring them to commit to making investment decisions based solely on material financial factors, which are commonly referred to as “pecuniary factors” (as derived from the now-superseded Trump administration’s investment duties regulation that was adopted in 2020). The phrase, “pecuniary factors” is a loaded one since it has been broadly understood (dating back to when the terminology first appeared in the Trump administration’s notice of proposed rulemaking) to engender extreme skepticism that ESG characteristics can ever qualify as pecuniary or material financial factors. Moreover, in many of the bills that have been introduced over the last year, there is often an express presumption that “pecuniary factors” do not include the consideration of the furtherance of social, political, or ideological interests.

Florida’s HB-3, which took effect on July 1, is a leading example of this kind of anti-ESG legislation, but many other states have taken this approach as well, as shown in the table that follows in the next sub-section. To a manager seeking to do business with a state that has either enacted or is considering such restrictions, there is concern that if the manager uses ESG factors in any way in its investment process, it will be prohibited from managing the state’s retirement assets, regardless of whether the manager is seeking to promote an ESG goal or other related impact goal or focus. This concern stems from the interpretive uncertainties these laws raise such as (i) what does it mean for something to be a pecuniary factor, (ii) when can a financial factor or characteristic be considered material, and (iii) when does one cross the line from using ESG factors as part of an integration strategy to using them for other purposes (such as a fund that has an impact strategy or social mandate)?

These challenges reflect the fact that anti-ESG laws are highly subjective, and their interpretations can vary among different state officials, which may shift over time in light of the changing political climate in states. For example, despite forceful messaging from state political leaders that managers who consider ESG are practicing “woke capitalism” that goes against the best interests of plan participants and beneficiaries, state pension plan fiduciaries may construe these new requirements narrowly in order to avoid having to remove their investment managers on the basis of ESG. Furthermore, the concern that a 3 LAST UPDATED – 9/13/22 136809818_13 ROPESGRAY.COM manager has crossed the line from using ESG factors as part of an integration strategy to using them for other purposes is exacerbated by the fact that neither the states nor the DOL has defined the different types of ESG investment strategies that exist (in contrast to the three-part framework that was included in the SEC’s 2022 proposed rule on enhanced disclosures by certain investment advisers about ESG investment practices as well as the analogous spectrum of funds with ESG features that appears in the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)). Given the lack of precise categories and definitions, it can be difficult for managers to know what exactly these laws were intended to prohibit.

As far as we are aware, only North Dakota has adopted legislation (SB2291)—which was one of the first anti-ESG laws in the U.S. to address investment aims and objectives with respect to handling state funds (retirement assets or otherwise) when it was enacted in 2021—specifically aimed at prohibiting the state investment board from investing funds for the purpose of “social investment” unless the board can demonstrate that the investment will perform at least as well as a similar non-social investment. Based on the current version of the statute as last amended earlier this year, the law provides that “social investment” refers to the “consideration of socially responsible criteria and environmental, social, and governance impact criteria in the investment or commitment of public funds for the purpose of obtaining an effect other than a maximized return at a prudent level of risk to the state.” In other words, the North Dakota statute is focused on preventing the state investment board from selecting impact funds that are specifically pursuing ESG or collateral social goals to the detriment of returns, as opposed to funds that use ESG as part of good faith financial risk analysis.

Despite the increased prevalence of these anti-ESG bills (and enacted laws) in 2023, we have not observed major changes with respect to either the investments the state plans are making or the managers the plan investment boards are selecting. Instead, we have started seeing a re-allocation of risk. In states where these laws are now on the books, plan investment boards are required to ensure that they are investing based on pecuniary factors; however, the boards are turning to their managers and asking them to certify that the managers are not using state assets for advancing social or other types of collateral benefits. By taking that tactic, state plan investment boards are shifting the risk of noncompliance (at least in part) to their managers.

Anti-Boycott Laws and Restricted Lists

Many red states opposed to ESG investing have also created restricted lists, which target financial institutions that allegedly boycott industries like fossil fuel and firearms. Several states such as Kentucky, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia have enacted these anti-boycott laws in the last two years, which authorize the state comptroller or treasurer to maintain a list of restricted financial institutions that will be barred from contracting with or doing business with the state (including, being selected to manage state pension assets).

The implementing statutes establish a process for adding a financial institution to a restricted list, which typically involves the comptroller or treasurer’s office looking at public statements by senior executives of a targeted financial institution, checking the signatories of the various climate coalitions like Climate Action 100, the Net Zero Banking Alliance and the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, reviewing index data compiled by third-party vendors such as MSCI’s ESG Ratings service, and sending out questionnaires to financial institutions soliciting information on their investment processes and strategies. Once all of the information is compiled, the comptroller or treasurer’s office will generate a list, which gets periodically updated.

While it is not always clear how a financial institution ends up on one of these restricted lists (in total, 30 institutions appear on one or more of the four state lists that have been made publicly available), once an institution is added, there is a sense of clarity as to what the consequences are—namely, the institution will be barred from transacting with the state unless it ceases to engage in the alleged boycotting activity. Additionally, since the process for getting removed from the list is typically laid out in the statute or other guidance from the state, an institution that ends up on one or more of these lists can devise a plan for responding to this designation. Nonetheless, the fear of being added to these lists can have dramatic and real consequences in terms of financial institutions changing their investment practices and/or withdrawing from global climate coalitions to avoid the outcome of getting placed on a restricted list.

When the initial lists were being compiled last year, it was suspected that they would be quite extensive based on the fact that the Texas State Comptroller sent out its questionnaire to over 130 asset managers. However, these lists have ended up being considerably shorter. Furthermore, these lists have been more nuanced and fine-tuned than initially anticipated, with states delineating between restricted institutions and restricted funds. For example, in Texas, where the Comptroller has published three iterations of its list (Oklahoma’s Treasurer also came out with a revised list in August 2023), there are currently 4 LAST UPDATED – 9/13/22 136809818_13 ROPESGRAY.COM 11 banks and financial institutions included, but over 350 impact or dual-mandate funds included—many of which are managed by institutions that have not been included on the restricted list.

Fiduciaries of the public plans have also pushed back on the use of these restricted lists, as evidenced by the ongoing dispute between the Oklahoma Treasurer’s office and the board of trustees overseeing the Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System (OPERS). Back in August, the OPERS board voted in favor of a move that would exempt the pension fund from having to terminate contracts with blacklisted firms based on an exemption for plans that determine that such requirement would be inconsistent with fiduciary responsibility with respect to the investment of entity assets. Since then, members of the OPERS board and the Treasurer’s office have gone back and forth, disagreeing over the applicability of this exemption. Furthermore, the Treasurer (who has the lone dissenting vote in the OPERS vote to invoke the exemption) has been lobbying members of the legislature to clarify or walk back the fiduciary exemption.

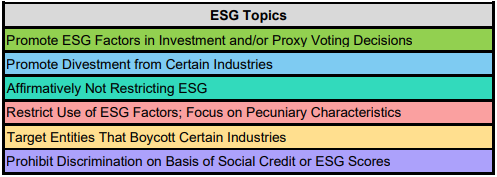

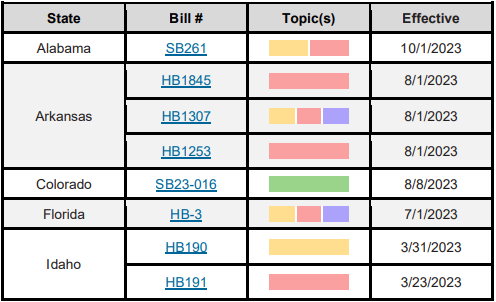

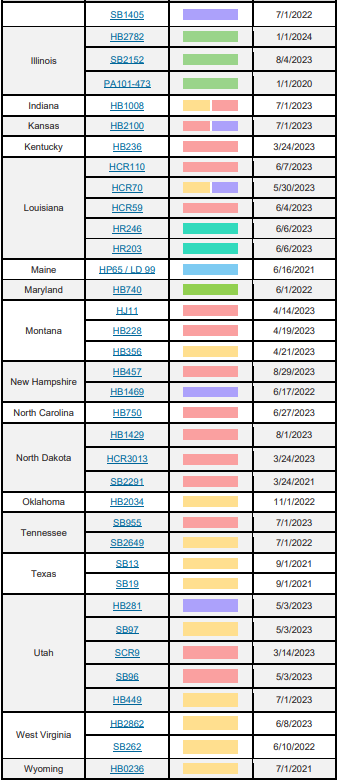

Laws In Effect or Expected to Take Effect in 2023

In Part II of this paper, we provide high-level summaries of the legislation and pronouncements that each state has recently adopted or considered regarding the role of ESG factors in public pension investing. As for the bills that have been adopted, we have identified the following items and have assessed the ESG topic(s) that each encompasses:

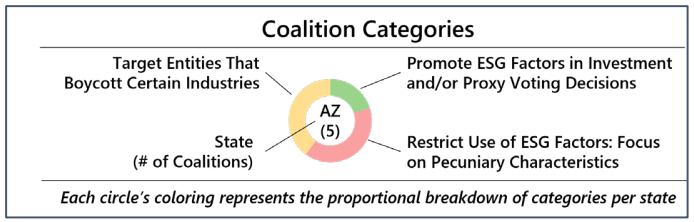

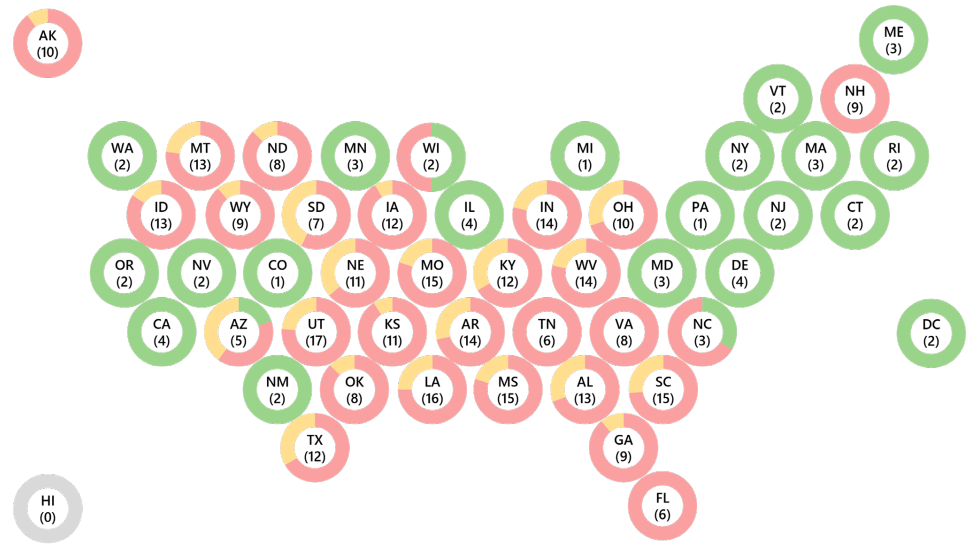

Map of Coalition Activities Among the States

As of October 31, 2023

Multi-State Coalitions

Besides legislation and regulation, elected officials in many states have engaged in collective action to demonstrate their support for or against the use of ESG factors in public pension investments. Coalitions enable state officials to articulate their ESG positions in a more efficient manner and amplify their voice. One of the most prominent examples of coalition activity this year has been the litigation initiated by the State Attorneys General of Utah and Texas, along with 24 of their counterparts against the DOL seeking to vacate the 2022 ESG rule on the basis that the rule undermines key protections for retirement plan participants, oversteps the DOL’s authority under ERISA and is arbitrary and capricious in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act. On September 22, 2023, Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk of the Northern District of Texas granted the DOL’s motion for summary judgment, in an opinion that was largely deferential to the agency pursuant to the Supreme Court’s longstanding Chevron doctrine. The opinion noted how the 2022 ESG rule “changed little in substance from the [Trump administration’s 2020 rule] and other rulemakings,” and it affirmed the rule’s neutrality regarding ESG, citing an amicus brief for the proposition that the “[2022 ESG rule] provides that where a fiduciary reasonably determines that an investment strategy will maximize risk-adjusted returns, a fiduciary may pursue the strategy, whether pro-ESG, anti-ESG, or entirely unrelated to ESG.” However, this story is not over yet—on October 26, 2023, the states filed a notice of appeal with the Fifth Circuit, so it is possible the states’ lawsuit could be revived.

Considerations for Asset Managers

For asset managers who may already be subject to ERISA’s requirements when it comes to investing money on behalf of public retirement plans, the labyrinth of state laws and guidance in this area adds a new layer of complexity. When reviewing their investment policies and marketing materials for funds and managed accounts they oversee, now they must take these requirements into consideration, to the extent they already accept or plan to accept state retirement plan money. While these state laws may seem contradictory, we believe it is generally still possible for managers to thread the needle and continue to retain both red and blue state mandates by keeping in mind the following considerations:

- Be measured and careful in communications – It is critically important for managers to be very measured and careful when speaking with state officials. All communications—whether written or oral—must be accurate, precise and consistent with statements being made to other investors. For instance, if a manager takes into account ESG considerations as part of an integration strategy, it is important that the manager not overstate that detail and make it the focus of its communications with the plan fiduciaries or other state officials. At the same time however, the manager should not understate the role ESG factors play in its investment process. Caution, care and moderation are the order of the day to best ensure that the manager can continue to work with a diverse array of investors.

- Be thoughtful when responding to state inquiries – Even if they seem innocuous, communications between managers and state officials could be used as the basis for a determination or allegation that a manager is not acting consistently with its fiduciary duties. Communications also could be viewed as a basis for inclusion on that or another state’s restricted list. It is important to remember that when dealing with state governments, open public records laws (similar to FOIA in the federal context) are always at play. Managers can never assume that anything being communicated to state officials or employees (whether it is oral or written) will remain confidential. Put another way, managers need to align their private and public messaging and ensure that whatever is said to one state would be okay for the entire LP base to hear as well.

- Know what your contracts require – As discussed at the beginning of this white paper, state laws regulating the fiduciaries of the public retirement systems have historically tracked ERISA and the DOL’s interpretations thereunder. As a result, a fund’s investment documentation with a state pension plan would often refer to ERISA and just say that the state plan would be treated as an ERISA partner in order to ensure that it would be getting the highest level of fiduciary protection under U.S. law. However, in light of the divergence in state and federal retirement laws recently due to the ESG issue, managers need to make sure that they understand what contractual promises mean and that they can actually comply, and are complying, with the various state laws. For some states where these anti-ESG laws have been adopted, contractually agreeing to treat the public retirement plan as an ERISA investor could run afoul of state law.

Read the full whitepaper here.

Print

Print