Steve Newman is a Contributing Author at The Conference Board ESG Center in New York. This post relates to a Conference Board research report authored by Mr. Newman and is based on Corporate Environmental Practices in the Russell 3000, S&P 500, and S&P MidCap 400: Live Dashboard, a live online dashboard published by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; Does Enlightened Shareholder Value add Value (discussed on the Forum here); and Stakeholder Capitalism in the Time of COVID (discussed on the Forum here) both by Lucian Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita; How Twitter Pushed Stakeholders Under The Bus (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Anna Toniolo; and Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy – A Reply to Professor Rock (discussed on the Forum here) by Leo E. Strine, Jr.

Climate Risk Disclosure Are on the Rise but Remain the Domain of Large Companies and Regulated Industries

Climate risk disclosures increased in 2022 from the previous year, with S&P 500 companies still the most likely to disclose; specifically, 60% of companies in the Russell 3000 Index still did not report climate risk in 2022, compared to only 26% of companies in the S&P 500.

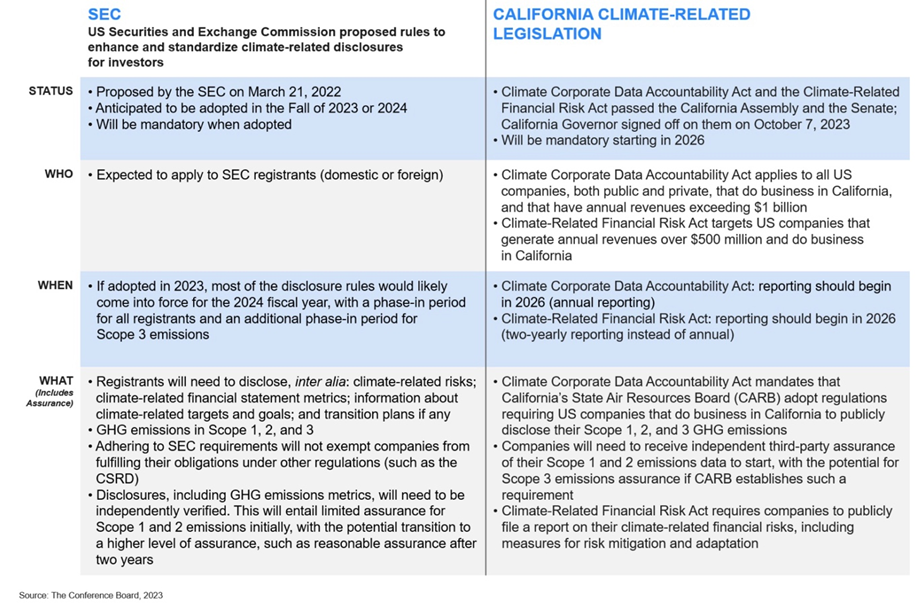

Climate risk disclosure was most prevalent in sectors with existing regulatory and reputational risks related to climate change, including utilities (93%), real estate (77%), and energy (75%). The lowest rates of climate risk disclosure were in health care (15%), communication services (23%), and IT (24%).

![]()

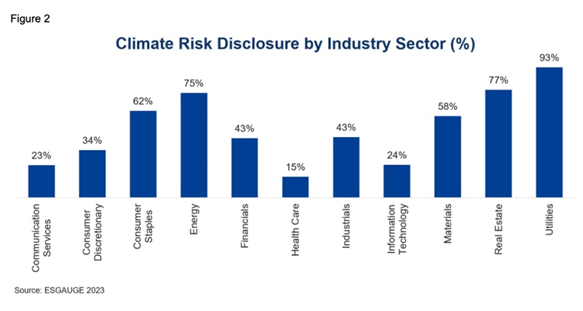

Industries with the highest rate of climate risk disclosure typically had climate target years furthest in the future; for example, in utilities it was 2045, while in energy it was 2040. Those with the lowest disclosure had a target year closest to the present date (health care and IT in 2034, with communication services having the target year farthest in the future relative to the sector’s average climate risk disclosure rate). Companies with regulatory and reputation risks associated with climate change are likely to have established governance structures and knowledge related to climate risks. They also tend to have a better understanding of what is needed to meet sustainability targets.

Board Accountability on Climate Will Increase

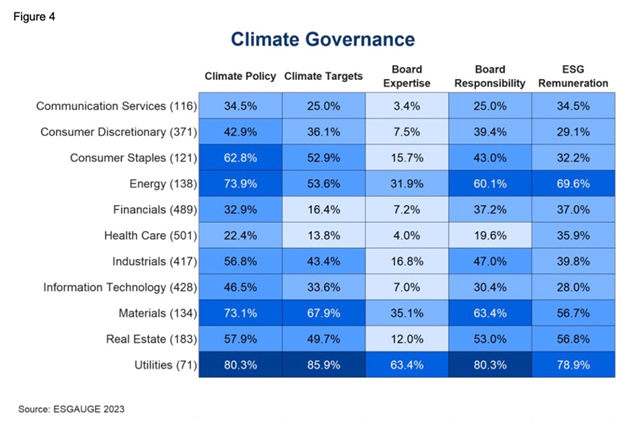

Among the Russell 3000, it was more common to disclose climate risk policies and targets than to:

- Assign board responsibility for climate (39%, or 1,160 companies).

- Disclose board climate expertise (12%, 364 companies); or

- Link ESG performance to compensation (39%, or 1,169 companies).

This will change. The disclosure requirements in the SEC draft rule on climate-related disclosures, the California climate-related legislation, the CSRD, and CSDDD4 will all increase boards’ responsibilities relating to climate (see box “Regulatory and Self-Regulatory Efforts to Standardize Climate Risk Disclosures”).

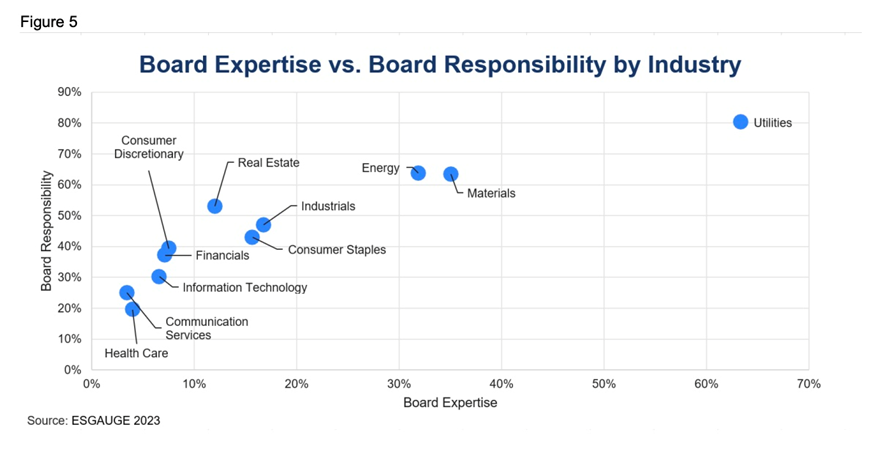

The sectors with the current highest rates of policy and target disclosures—utilities, materials, energy, and consumer staples—also had the highest rate of board responsibility and expertise, as well as ESG-linked management compensation. There is a strong, although not linear, correlation between board responsibility and board expertise across sectors. In most cases, companies that disclosed in 2022 were more likely to assign board responsibility for climate than to have board expertise in climate. This finding is consistent with those in prior reports by The Conference Board, which discuss the general need for clear board governance relating to environment issues, but the risks associated with recruiting directors with highly specific expertise (especially if that expertise is not accompanied by broader board and business strategy experience). As previously noted, board fluency in relevant ESG topics is likely to be more valuable than expertise.

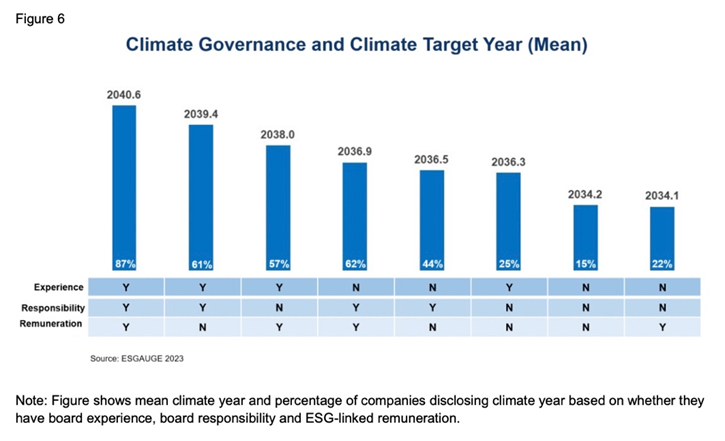

The rate of disclosure of climate target years was higher in organizations that implement ESG-linked compensation structures. Companies with both board climate expertise and responsibility were considerably more likely to incorporate ESG performance metrics into their remuneration strategies.

Notably, in companies lacking any of the three forms of climate-related governance and compensation (15%), the reported target year tended to be the earliest, typically set at 2034. In contrast, organizations that checked all three boxes tended to set their target years further into the future, often around 2040.

This divergence in target years likely reflects both the realities of, and the understanding of the complexities and risks associated with, achieving a net-zero transition. At companies that are responsible for high levels of greenhouse gas (GHG emissions, climate goals are likely to be subject to greater scrutiny (including at the board level) and integrated into a broader strategy aimed at transitioning to and investing in a low-carbon economy. Additionally, industry regulations and sector-specific challenges play a role. Companies outside the utilities, energy, and materials sectors, which may have set GHG targets without the same rigorous internal processes, may wish to revisit those targets. At a minimum, boards should be aware that the increased due diligence required by upcoming SEC and EU regulations may prompt companies to reset their targets.

Climate-related firm performance and executive compensation. According to a review of incentive plan compensation metrics conducted in collaboration with ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in 2023, 40.4% of S&P 500 companies and 22.7% of Russell 3000 companies link their executive compensation to carbon footprint and emission reduction performance metrics. Only two years ago, these percentages were 14.8% and 7.3%, respectively. Considering the new regulation, companies may be even more inclined to link compensation to climate related ESG performance.

However, integrating ESG performance goals into compensation packages presents a greater challenge compared to traditional financial metrics.[1] For this reason, The Conference Board has advised that companies proceed with caution as they redesign their incentive plans to include these new types of metrics. To the extent that the company sets specific, quantitative sustainability targets, these targets should be time bound and rooted in scientific principles, particularly in the case of climate and other environmental objectives. In all cases, companies should articulate why integrating or adjusting ESG goals within compensation programs aligns with their business strategy.

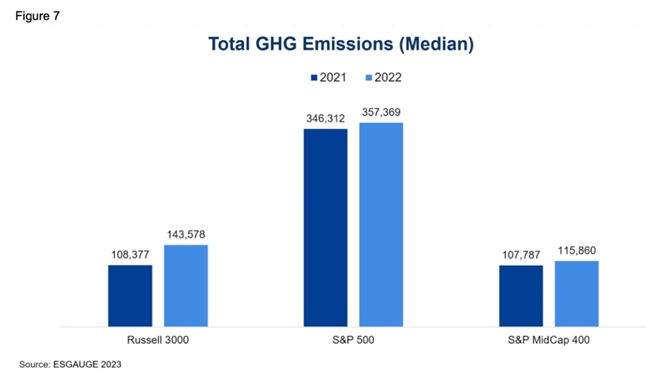

The Biggest Companies Produced the Most Emissions but the Least Annual Relative Increase

In November 2022, officials at COP27 reiterated the need for countries to revisit and strengthen their emission reduction targets for 2030. This call-to-action places significant pressure on the world’s most-emitting countries to formulate robust and ambitious climate plans, as well as to implement stronger policies aimed at curtailing GHG emissions. In 2022, companies in the S&P 500 generated the highest level of GHG emissions ever disclosed but demonstrated the smallest proportional increase in median total GHG emissions (3%), compared to S&P MidCap 400 companies (7%) and companies on the Russell 3000 Index (32%). This relatively lower year-on-year change among the larger companies on the S&P 500 was likely due to greater investment to control or reduce emission production.

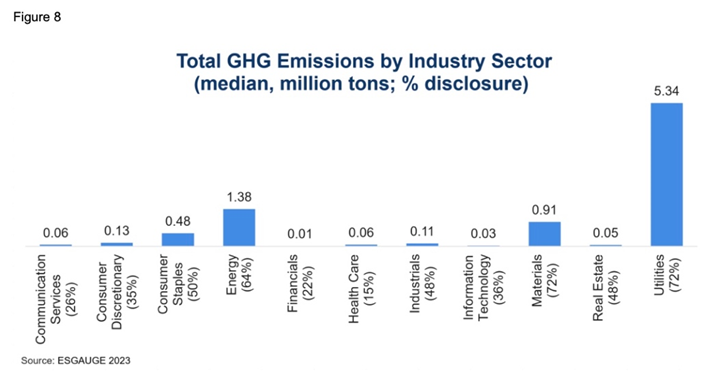

The utilities, energy, and materials sectors had the highest rate of GHG emission disclosure and the highest total median GHG emissions. Energy producers were the highest GHG emitters, followed by companies in the materials sector, which encompasses energy-intensive production to make things such as cement, steel, and aluminum. Reporting in these sectors is typically more regulated due to their environmental impact.

Expanding scope—Scope 3 emission reporting. The proposed SEC ruling and many securities exchanges focus on Scope 1 (direct) and Scope 2 emissions (indirect, i.e., emissions from purchased power), with Scope 3 emissions (indirect, i.e., supply chain) only reported if the company is already doing so or if it is material to the company. However, pressure is mounting to compel companies to extend their reporting to encompass emissions reporting throughout their supply chains. Notably, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act both require Scope 3 emission disclosure, while the proposed SEC ruling would require it if the Scope 3 emissions are material or if the company has set a GHG emissions target or goal that includes Scope 3 emissions. Furthermore, the Science-Based Target Initiative stipulates that companies account for supply chain emissions in their targets and strategies.

The importance of including Scope 3 emissions in reporting was underscored by the fact that such emissions accounted for the largest amount of GHG emissions in all sectors except energy, utilities, and materials. CEOs have identified supply chain disruptions as a top-five high-impact issue in 2023,[2] and supply chains will continue to be a key focus even as ESG concerns mount. The SEC climate disclosure rules, the California climate-related legislation, and the CSRD are expected to place greater scrutiny on companies to gain a more comprehensive understanding of emissions originating from their supply chains, in line with national efforts to reduce GHG emissions.

While most public, investor, and corporate attention is focused on carbon emissions, there are many different types of GHG emissions. Other GHGs are often industry-specific, with no correlation to company size or index but may contribute significantly to climate change:

- Information technology: This sector has emerged as a substantial emitter of ozone-depleting substances, nitrogen trifluoride, and perfluorochemicals (PFCs).

- Health care: This sector produces a considerable amount of volatile organic compounds and PFCs.

- Consumer staples: This sector produces large amounts of methane and hydrofluorocarbons.

Given that the SEC regulations speak to the full range of GHG emissions, it is important for boards and management to familiarize themselves with the full range of relevant GHG emissions at their company and supply chain.

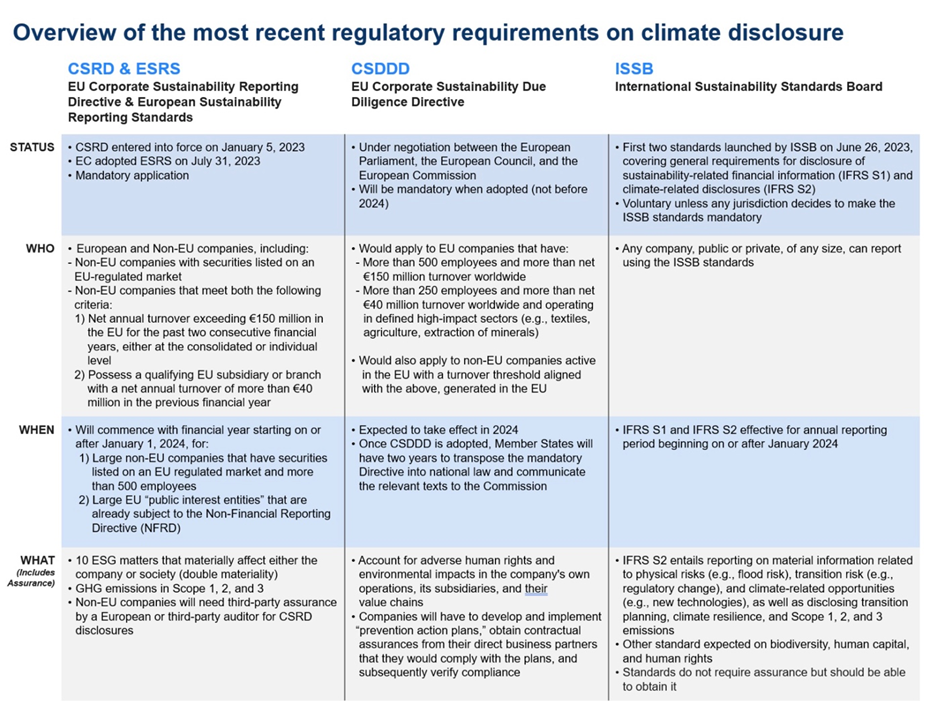

Regulatory and Self-Regulatory Efforts to Standardize Climate Risk DisclosureRecently, we have seen multiple efforts by regulators in the US and Europe to standardize climate-related disclosures. However, because of the lack of effective coordination and consistency among these regulatory regimes, companies are now facing multiple layers of overlapping and inconsistent reporting obligations. Some of the more notable developments include:

The emerging regulatory regime, especially for large US-headquartered multinational companies, is characterized by the following:

Rather than aiming for minimal compliance with each of these distinct regulatory regimes, which can result in a complex hodgepodge of reporting, companies may find it more efficient and effective to aim higher for more consistent reporting around the world. Even though CSRD’s reporting requirements may not come into effect for many US firms for a few years, companies should begin to build the reporting infrastructure now.

|

Renewables Are on the Rise

The proposed SEC climate reporting requirements will compel companies to both disclose emissions and actively work toward reducing them. Renewable energy is emerging as an attractive entry point for smaller enterprises to help meet these goals, thanks to an increasingly favorable return on investment. While concerns about transition costs persist, a substantial portion of global CEOs (49%) and C-Suite executives (59%) surveyed in The Conference Board C-Suite Outlook for 2023 believe that the shift toward renewable energy will yield significant benefits for their organizations. Investing in renewables can not only lead to direct cost savings for businesses, but it also offers a more sustainable approach than relying on offsets, as the latter entails operational costs and can be viewed as a strategy for emission avoidance rather than genuine reduction.

In support of this transition, global renewable energy production is expected to jump by one-third in 2023: by 107 gigawatts (GW)—the equivalent of Germany and Spain’s combined power consumption—to more than 440 GW. Two-thirds of this increase is expected to come from photovoltaics, with global photovoltaics manufacturing potential set to double in 2023–24.[3] Meanwhile, new policy measures are leading to significant increases in renewable production in the US,[4] facilitating accessibility to businesses of all sizes.

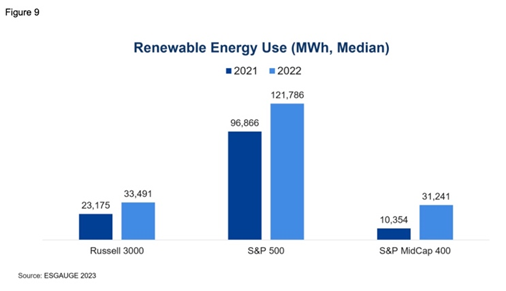

Just like emission reduction programs and other climate change risk mitigation strategies, renewable energy use is on an upward trajectory: in fact, year-on-year increases in renewable energy adoption have outpaced the corresponding growth in median GHG emissions; over 50% of companies in the S&P 500 disclosed renewable use, aligning with the observed trend of lower GHG emissions. However, just like in the emission area, only 26% of S&P MidCap 400 companies reported using renewable energy in 2022, yet they showcased the most significant year-on-year surge in renewables adoption, at 302%.

This marked uptake in renewable energy use among smaller companies could be attributed to a combination of factors, such as:

- The relative attractiveness of self-producing energy.

- Increased return on investment for renewable energy initiatives considering high global energy prices; and

- Greater access for smaller companies to power-purchase agreements (PPAs), including virtual PPAs, which eliminate the need for substantial upfront capital investment for solar installations.

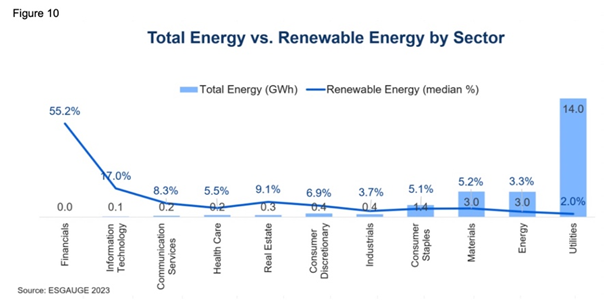

There exists an inverse relationship between overall energy consumption and the percentage of renewable energy different sectors use: the sectors with the highest energy consumption— utilities, materials, and energy—demonstrated a relatively lower proportion of renewable energy adoption. This can be attributed to various factors, including their historical reliance on fossil fuels, infrastructure limitations, and challenges transitioning to renewable sources.

However, when viewed in absolute terms, utilities, materials, and energy reported the greatest renewable use. It is encouraging to note that many companies in the utilities and energy sectors are investing heavily in the transition to renewables, although clearly more substantial investment, infrastructure development, and innovation is required to facilitate the adoption of cleaner energy alternatives.

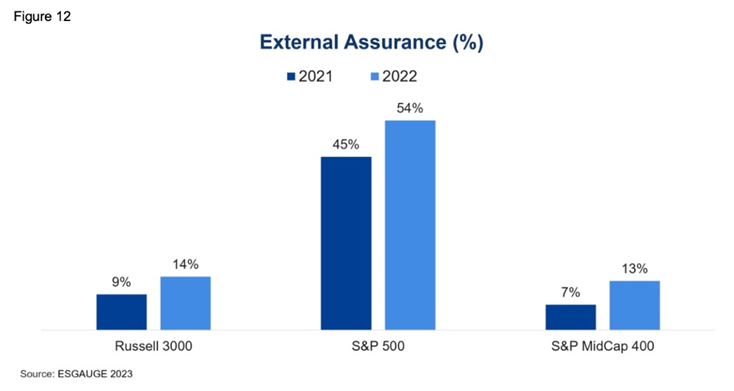

More Robust Climate Reporting Will Require Companies to Increase External Assurance

As noted above (see the box titled “Regulatory Efforts to Standardize Climate Risk Disclosures”), there are several initiatives underway to standardize reporting on climate and other ESG topics, including SEC disclosure regulations, the EU’s CSRD, and the ISSB standards.

While the SEC and EU rules will set the reporting obligations for companies under their jurisdiction, the ISSB standards may well set expectations for firms in the US and Europe, as well as being adopted by regulators to directly apply to companies outside the US and EU.

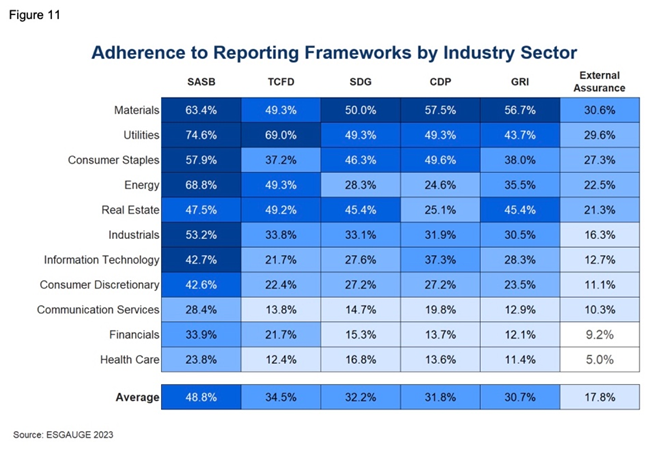

Large multinational companies can therefore expect to need to adhere to the SEC, CSRD, and ISSB standards. But even so, other voluntary reporting frameworks are likely to remain in place, including: the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), with which the SEC draft rule is aligned; the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); and the framework established by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

According to ESGAUGE data, the most common climate risk reporting frameworks to which sustainability disclosures refer are:

Given ISSB’s incorporation of SASB and CDP (which will ultimately transition into IFRS Sustainability Standards using the ISSB Framework), and the SEC’s alignment with TCFD, we may see an increase in adherence to the first two frameworks listed in the table above and a decline with respect to the other three. In any event, we should see an increased use of assurance services with respect to climate disclosures.

For instance, per the CSRD, non-EU companies’ disclosures will need third-party assurance by a European or third-party auditor. The proposed SEC rules and the California climate-related legislation will also require independent verification, at least for Scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions.

Conclusion

Climate change poses a significant but not insurmountable challenge, and history has shown the capacity of humankind to overcome formidable obstacles. Perhaps one of the most striking examples of successful climate protection legislation to date is the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement made in 1987 that effectively banned chlorofluorocarbons in a bid to reverse the damage to the ozone layer.

The trend toward climate-related disclosures is unmistakable, signaling a commitment to more comprehensive reporting and transparency. This will be strengthened by the SEC and CSRD’s climate reporting standards, while the growing emphasis on external assurance will add an extra layer of accountability to climate-related reporting.

The largest corporations are leading the way in terms of climate-related disclosures and minimizing the increase in GHG emissions, despite often being among the biggest contributors to GHG emissions. This underscores their pivotal role in the transition toward renewable energy: over 50% of companies on the S&P 500 now report using renewable energy, showcasing a commitment to more sustainable practices.

Companies with robust climate governance were often found in highly regulated industries associated with significant emissions—utilities, energy, and materials—and tended to set climate goals further into the future, reflecting a realistic assessment of the time required for meaningful change. By comparison, companies with less at stake (or perhaps a more limited understanding of climate issues) tend to set short-term targets.

Substantial opportunity remains to address climate, especially among smaller and less regulated companies. While their efforts will need to be tailored to the company’s specific circumstances and strategy, they can benefit from the experience of their larger counterparts, including in ensuring that their GHG policies and targets are not set in isolation, but as part of the company’s broader board-approved business strategy.

Methodology and Access to DataThis report highlights key findings from an analysis of the disclosure of climate-related and sustainability reporting metrics by 2,969 companies in the Russell 3000 Index conducted by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE. Comparisons are made with companies in the S&P 500 Index and the S&P MidCap 400. Data analysis is complemented with insights from a series of roundtables and focus groups held by The Conference Board on the topic of climate-related disclosure in the course of 2023. Data comprising 86 reported metrics were compiled by ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE from companies’ publicly reported sustainability information, including annual reports, proxy statements, sustainability/CSR reports, and company websites. This report analyzed and presented findings from 52 core metrics, which had additional levels such as rates of disclosure and intensity across each of the three indexes, company size (revenue and asset value), and business sector. The full dataset for this report can be accessed and visualized through an interactive online dashboard available at https://conferenceboard.esgauge.org/environmental. This report presents key findings for climate-related disclosures; greenhouse gas, CO2, CO, and other atmospheric emissions; energy and electricity use; and climate-related reporting and external assurance, with the following key assumptions:

|

Endnotes

1Merel Spierings, Linking Executive Compensation to ESG Performance, The Conference Board, October 2022(go back)

2Chuck Mitchell et al., C-Suite Outlook 2023: On the Edge: Driving Growth and Mitigating Risk Amid Extreme Volatility, The Conference Board, January 2023.(go back)

3Cristen Hemingway Jaynes, 2022 Was a Record-Breaking Year for Renewable Energy in the UK, World Economic Forum, January 6, 2023.(go back)

4International Energy Agency, Renewable Power on Course to Shatter More Records as Countries Around the World Speed up Deployment, IEA press release, June 1, 2023.(go back)

Print

Print