Steve Newman is a Contributing Author at The Conference Board ESG Center in New York. This post relates to a Conference Board research report authored by Mr. Newman and based on Corporate Environmental Practices in the Russell 3000, S&P 500, and S&P MidCap 400: Live Dashboard, a live online dashboard published by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; Will Corporations Deliver Value to All Stakeholders? (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita; How Twitter Pushed Stakeholders Under The Bus (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel and Anna Toniolo; Restoration: The Role Stakeholder Governance Must Play in Recreating a Fair and Sustainable American Economy – A Reply to Professor Rock (discussed on the Forum here) by Leo E. Strine, Jr.; and Stakeholder Capitalism in the Time of COVID (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Kobi Kastiel, and Roberto Tallarita.

Biodiversity Loss is an Interconnected and Existential Business Risk

Biodiversity is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem, and healthy ecosystems offer value and resilience through the goods and services they provide that underpin society and businesses. Declining biodiversity could impede wealth creation: according to a 2020 report from the World Economic Forum (WEF), more than half of the global GDP, or about $44 trillion, relies to some extent on nature and biodiversity.![]() [1]

[1]

The loss of biodiversity is both a distinct risk and intertwined with other business risks such as climate change, water scarcity, and human rights. Biodiversity loss is among the top global risks to society;[2] in 2022, WEF forecast it to be among the top-three most severe risks over the next decade.[3] The UN reported in 2022 that up to 40% of the world’s land and 66% of the marine environment has been degraded or altered by human damage.[4] This damage threatens almost 1 million species[5] in what is becoming widely reported as the sixth mass extinction.[6] Moreover, according to the World Wildlife Fund, the world’s wildlife population recorded an average population decline of 69% between 1970 and 2022.[7] The destruction, degradation, overexploitation, and overdevelopment of the natural world have driven these losses to the extent that the UN has defined the loss of biodiversity as an existential threat.[8]

In our report on biodiversity and business published in 2021,[9] we highlighted not only the importance of biodiversity to humans but also how biodiversity loss can affect companies across sectors—by leading to resource scarcity, increased operational costs, liability risk, or reduced access to critical materials. Based on public disclosures, a relatively small percentage of companies understand or proactively manage their impact on biodiversity. The business case for biodiversity action has never been clearer, however, with biodiversity-related risks the new frontier of environmental, social & governance (ESG) strategies.

Biodiversity Policy Disclosures Are Low but Rapidly Increasing

The impact of biodiversity loss on a value chain is not always immediately felt, and, as such, biodiversity loss remains a blind spot for many companies around the world.[10] Establishing and disclosing a biodiversity policy is the first step in addressing the topic, after which companies can begin to measure impact and implement specific mitigation or regeneration strategies.

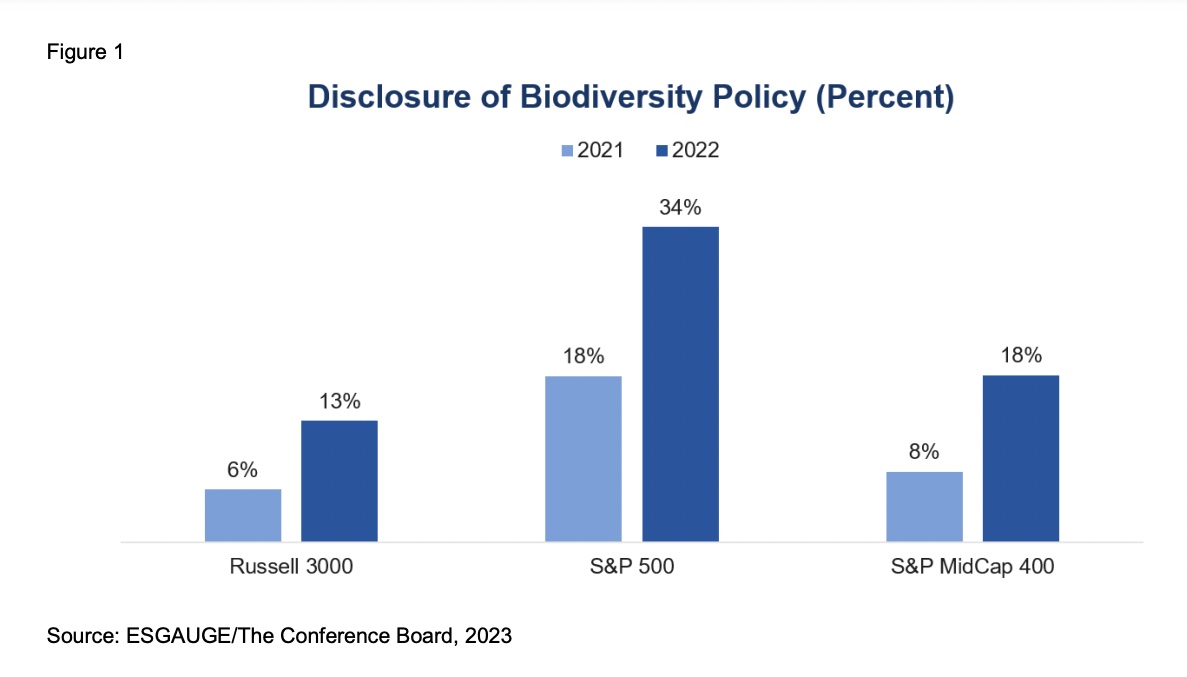

Around one-third (34%) of companies in the S&P 500 disclosed a biodiversity policy in 2022, while only 13% of Russell 3000 companies made such disclosures. The rate of disclosure nearly doubled from 2021 to 2022 in the S&P 500 and Russell 3000, indicating increased corporate attention to this topic alongside growing investor interest.

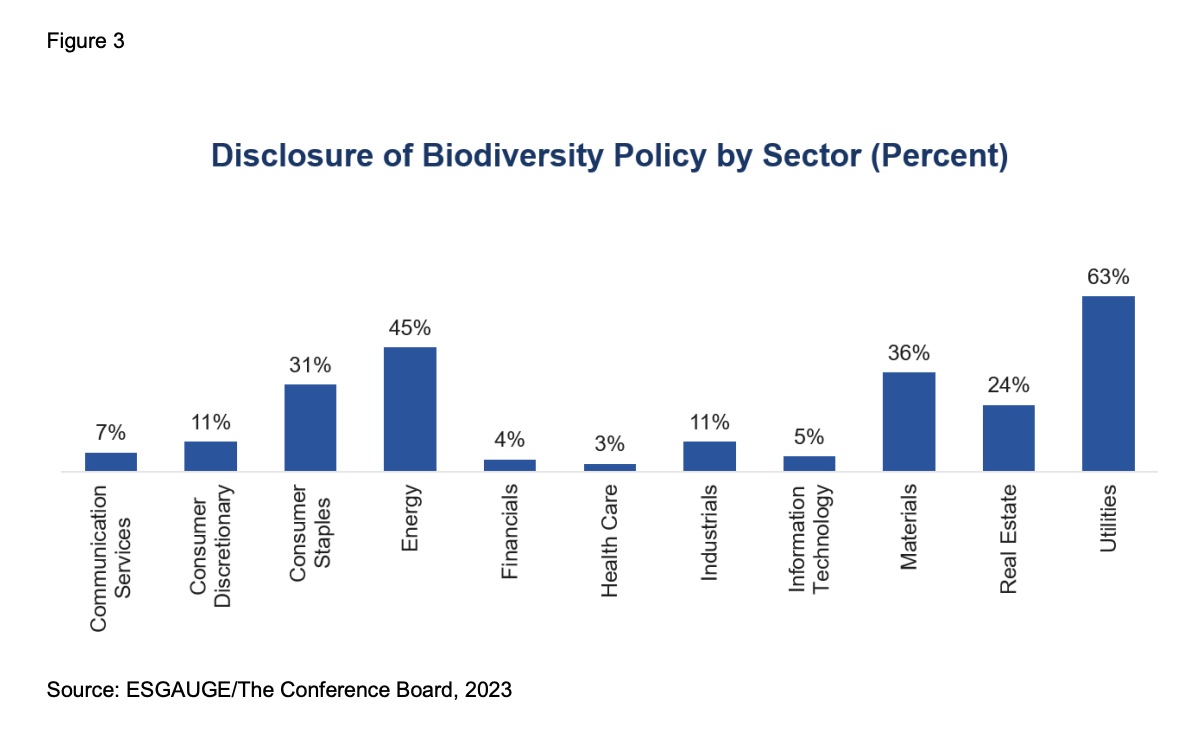

The highest disclosure rate of a biodiversity policy was in the utilities, energy, materials, and real estate sectors. This supports the findings of the 2022 S&P Global Corporate Sustainability Assessment that found utilities led on biodiversity commitments from a review of 3,753 companies.

Biodiversity impact on direct operations and via value and supply chains remains a nascent topic and voluntarily addressed in the US. Very few companies (12 out of 2,969; 0.4%), disclosed their impact on species and the number of species affected. Scarce reporting means that the numbers may not accurately reflect each sector’s impact; however, they serve as an indicator of the scale of business impact on species. It is important to note that not all species are equal in their biological value, nor in their risk to or resilience from impact, change, or extinction. Therefore, the number of species provides a small insight into biodiversity impact. Understanding which species are affected, and how, is necessary to develop appropriate mitigation and remediation action.

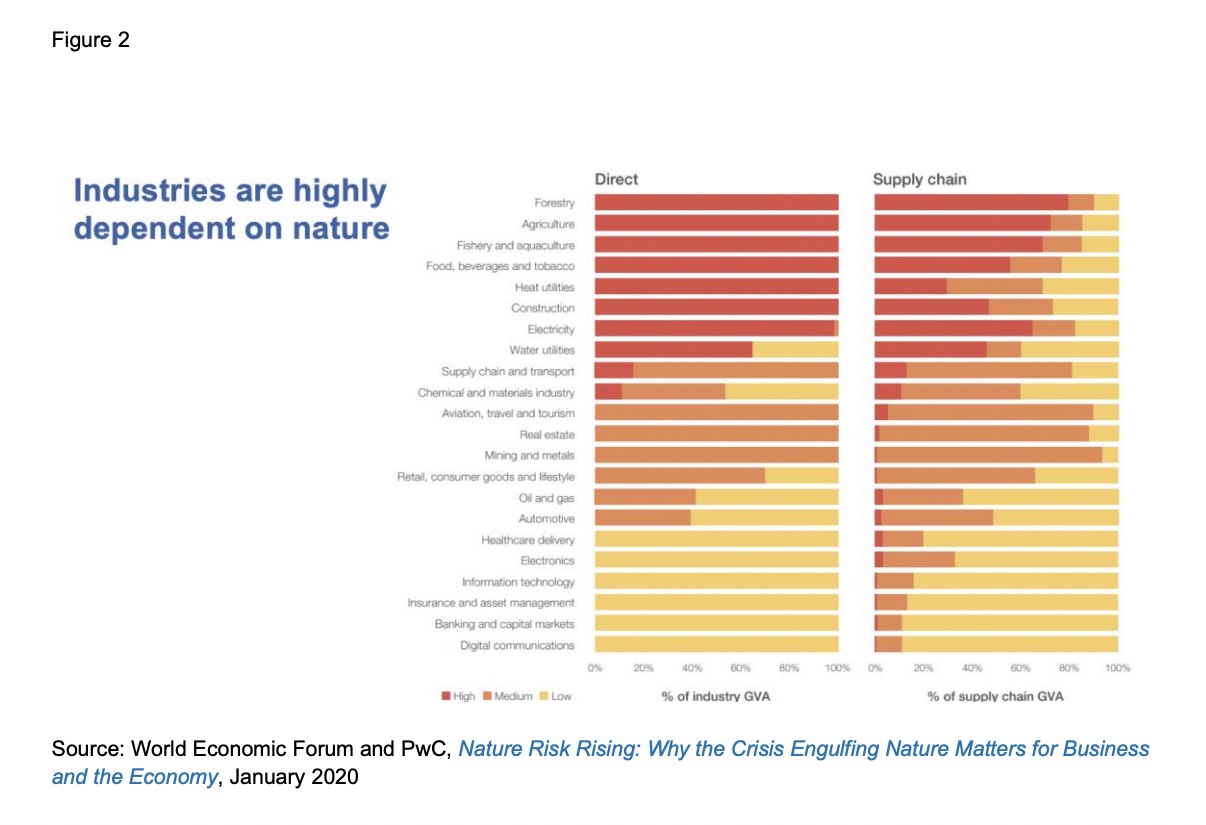

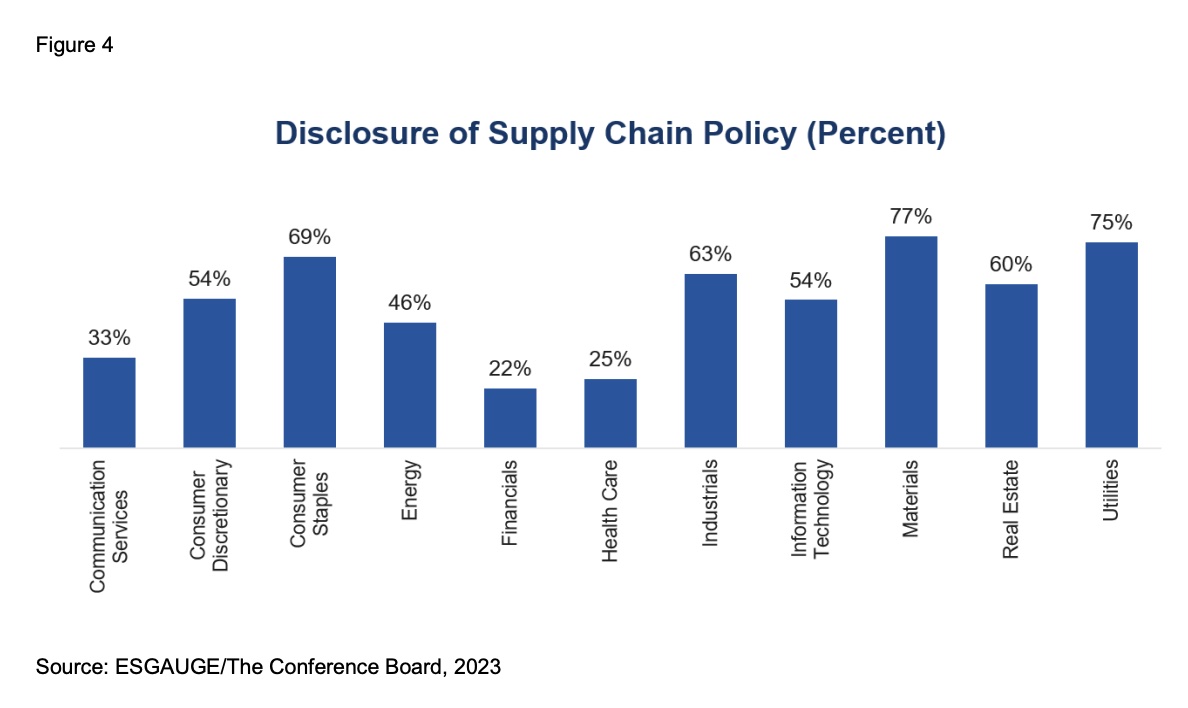

The most significant impact on biodiversity for most industries occurs in supply chains. This is why some organizations may choose to address biodiversity-related issues in other corporate policies, such as those governing their environmental supply chains. According to ESGAUGE data, in 2023 as much as 91.7% of S&P 500 companies and 75% of Russell 3000 companies adopted an environmental supply chain policy. The charts below illustrate the sector breakdown of biodiversity and supply chain disclosure.

The disclosure of biodiversity targets is also expected to increase. In 2010, 190 countries, under the UN Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD), established the Aichi Biodiversity Targets,[11] 20 goals to be achieved by 2020. However, no single target was met at a global level, and only six were partially achieved by the end of that time frame, a failure attributed in part to the lack of specific metrics and targets. Unlike climate-change commitments,[12] no target data were available for biodiversity. However, the lack of data availability does not mean US companies were not setting biodiversity targets. The 2022 S&P Global Corporate Sustainability Assessment reported just over 6% of S&P 500 companies set a biodiversity target.[13] However, there was a rapid rise in biodiversity disclosures and targets, indicating opportunities for companies to disclose more information on biodiversity including their policies, targets, and number and species of organisms affected.

Voluntary Frameworks and Regulatory Standards Regarding Biodiversity DisclosureUS companies should be aware of several emerging and updated regulatory standards and voluntary frameworks meant to increase business accountability regarding impact on biodiversity. These developments include: EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD): Applying to all companies with more than 250 employees, more than €40 million in net turnover or more than €20 million in total assets, and non-EU companies with a turnover above €150 million operating in the EU, CSRD requires companies to report their policies, due diligence processes, and principal risks related to environmental matters including biodiversity starting in their 2024 financial year. The draft European Sustainability Reporting Standard E4 specifically addresses biodiversity and ecosystems. In line with the goal of full restoration of all global ecosystems by 2050, companies must provide plans to ensure their business models and strategies are compatible with the transition to no net biodiversity loss by 2030 and net gain by 2050. Measurable biodiversity and ecosystem targets, biodiversity action plans, financial impact, risks, and opportunities must also be disclosed. EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD): CSDDD will require certain large EU and non-EU companies to set up mandatory due diligence practices to identify, prevent, or mitigate and ultimately end adverse impacts on human rights and the environment, fostering corporate accountability for environmental harm including biodiversity loss. CSDDD obliges companies to conduct due diligence not just on their own operations, but also entities in their value chain. It presents a critical opportunity to protect biodiversity, endangered species, and the environment. Voluntary frameworks are broadening their scope beyond environmental or climate disclosures to incorporate biodiversity and water in response to the following emerging disclosure requirements: Taskforce for Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is a science-based risk management and disclosure road map founded on the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) framework. TNFD captures areas not covered by TCFD such as biodiversity, soil erosion, and ocean plastics, and is based similarly on “scopes” that are categorized as direct operations, upstream, downstream, and financing. This voluntary initiative has received international political support, such as a June 2021 endorsement by the G7 finance ministers.[14] International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) framework provides a standardized reporting framework, with guidance currently released on general and climate-related disclosures. Over the next two years, ISSB will develop standards including biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecosystem services, considering the work of TNFD and other emerging rules. ISSB aims to form a global baseline for investors to compare companies’ performance in a range of topics including climate, water, land use, pollution, and invasive species. It is currently seeking feedback on its next two-year work plan that covers biodiversity, ecosystems, and ecosystem services. It remains to be seen how widely adopted the ISSB standards will be; despite some concerns, it is expected to replace many existing frameworks.[15] Science-Based Targets for Nature (SBTN)[16] provides a framework for assessing, prioritizing, target setting, acting on, and tracking nature similar to the Science-Based Targets Initiative for Climate Change. Launched in May 2023, the first release forms part of a multiyear plan to provide science-based targets for nature for companies of all sizes. Validation processes are being piloted in 2023 with a group of 17 companies, with expected rollout in early 2024. Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) conducted a stakeholder consultation in early 2023 to update and revise its Biodiversity Standard (304) to broaden reporting throughout the supply chain and incorporate new disclosures that connect direct drivers of biodiversity loss such as climate change, and biodiversity-related human rights impact. Global Biodiversity Framework will require large and transnational companies and financial institutions to disclose their risks, dependencies, and impact on biodiversity in their operations, supply and value chains, and portfolios by 2030. Known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), this landmark international agreement aims to safeguard and sustainably manage natural resources and deliver what the Aichi Biodiversity Targets failed to accomplish. Adoption of the GBF will establish targets to address overexploitation, pollution, fragmentation, and unsustainable agricultural practices to be more in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Even though the US did not endorse the GBF due to concerns over regulation of practices, intellectual property rights, and wealth redistribution,[17] it played an important role in shaping the CBD and pushing for the COP15 deal as a member of the 116 country–strong voluntary High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People. In December 2022 at COP15, the biodiversity counterpart of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27), 196 countries committed to increased biodiversity regulation. COP15 is a landmark agreement because it goes beyond climate change support to secure nature-based ecosystem services (e.g., water, pollination, etc.). As a result of these standardization processes and stakeholder pressure, large and multinational businesses including those based in the US should be prepared for nature and biodiversity disclosures to become the new norm. |

Carbon Credit Use Is Increasing but Biodiversity Benefit May Be Limited

Carbon credits and offsets are mechanisms that support emission reductions while system changes take place or innovative new practices are developed that allow organizations to decarbonize. This is typically achieved through afforestation projects that may support other sustainable objectives, such as biodiversity restoration or poverty reduction.

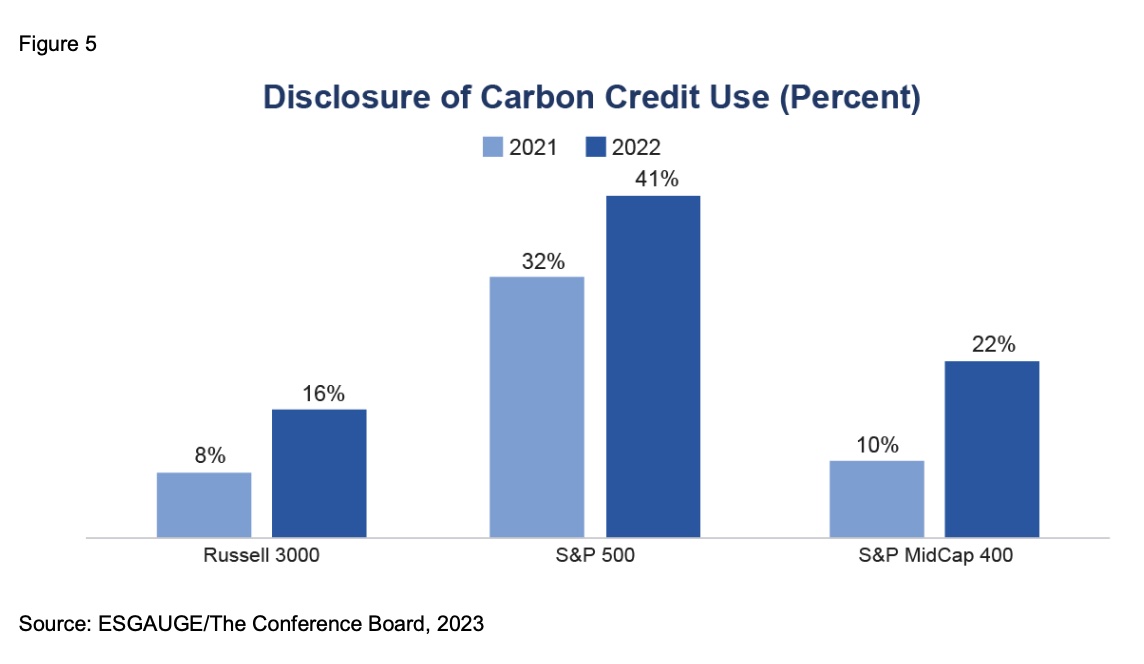

Disclosure of carbon credit use increased in 2022 and was greatest in S&P 500 companies. The use of carbon credits was relatively uniform across sectors in 2022, with no single industry exceeding 25% of companies disclosing carbon credit use. Internal carbon pricing remains a rarely used tool, with 39 companies out of the 2,969 analyzed by ESGUAGE reporting its use.

Biodiversity credits follow a similar approach as carbon credits, but with the goal of compensating for harm to natural habitats and species by funding or implementing conservation actions elsewhere. However, biodiversity is difficult to substitute and may require a significant time investment and location-specific approaches, making it more complex than emissions offsetting afforestation projects. Therefore, the specific types of biodiversity credits available can vary based on regional regulations, policies, and the nature of the development.[18]

Because carbon and biodiversity credits have different objectives, carbon projects may not benefit biodiversity unless diversity is built into the project. For example, monospecific afforestation projects (i.e., planting a single species of tree) have limited biodiversity benefits due to their inherent lack of diversity. Biodiversity credits are slowly emerging[19] but are unlikely to gain the scale of carbon credits due to their complexity. Combined with the current skepticism about a credit-based approach and the difficulties of verifying scope and scale,[20] companies should prioritize avoiding and reducing biodiversity loss.

Utilities Companies Use and Recycle More Water Than All Sectors Combined

Water and biodiversity as closely interrelated. To thrive, the environment needs clean and reliable sources of water, while water pollution is directly linked to biodiversity loss and the endangering of species.[21] According to the WEF’s Global Risks Report 2022, water scarcity is one of three global systemic risks of highest concern.[22] Increased withdrawal combined with more variability in rainfall means groundwater withdrawal exceeds replenishment rates in over half of the world’s aquifers.[23] For example, in 2022 Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the US, recorded its lowest level since it was filled in 1937.[24] To help address this, in January 2021 President Biden issued an executive order on addressing climate change both at home and abroad, and specifically to conserve, connect, and restore 30% of the country’s lands and water by 2030.[25]

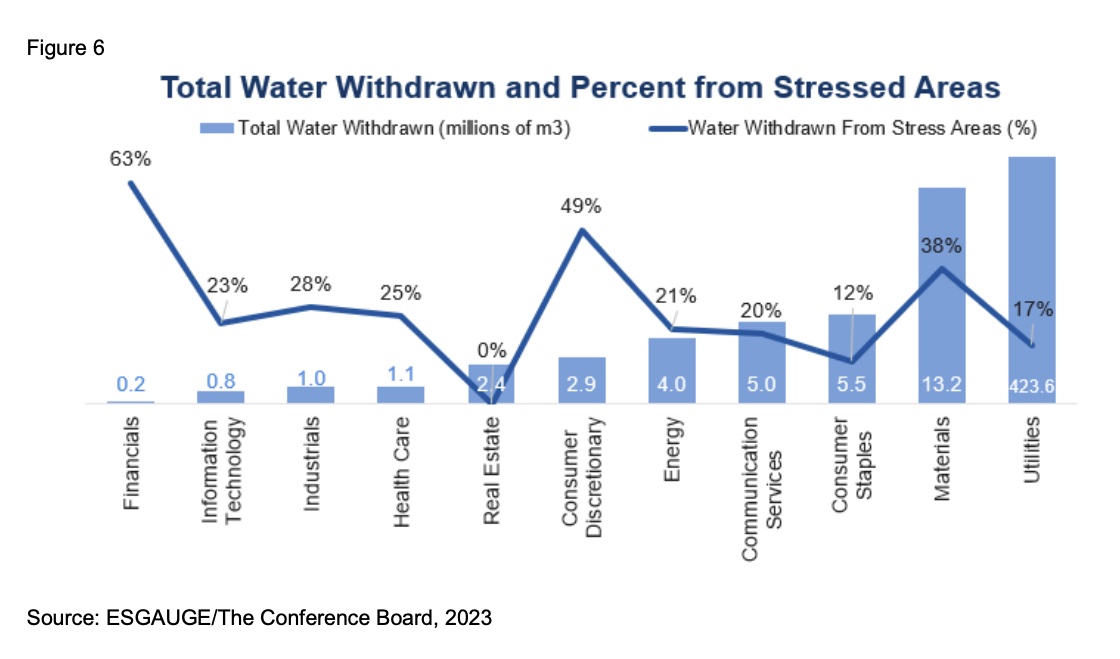

Companies that withdrew the most water in 2022 were in the utilities, materials, consumer staples, and consumer services sectors, according to the ESGAUGE survey. Indeed, the median volume of water withdrawn by companies in the utilities sector was more than 11 times that of all other sectors combined. Companies in the financial, consumer discretionary, and materials sectors withdrew the highest percentage from water-stressed areas. (Water stress areas are defined as those where the demand for water exceeds the available water supply, either because of natural scarcity or human factors such as population growth, economic development, and climate change. This includes areas with high or extremely high-water stress.) However, in absolute terms, utilities still withdrew more water from stressed areas than all other sectors from total water sources combined.

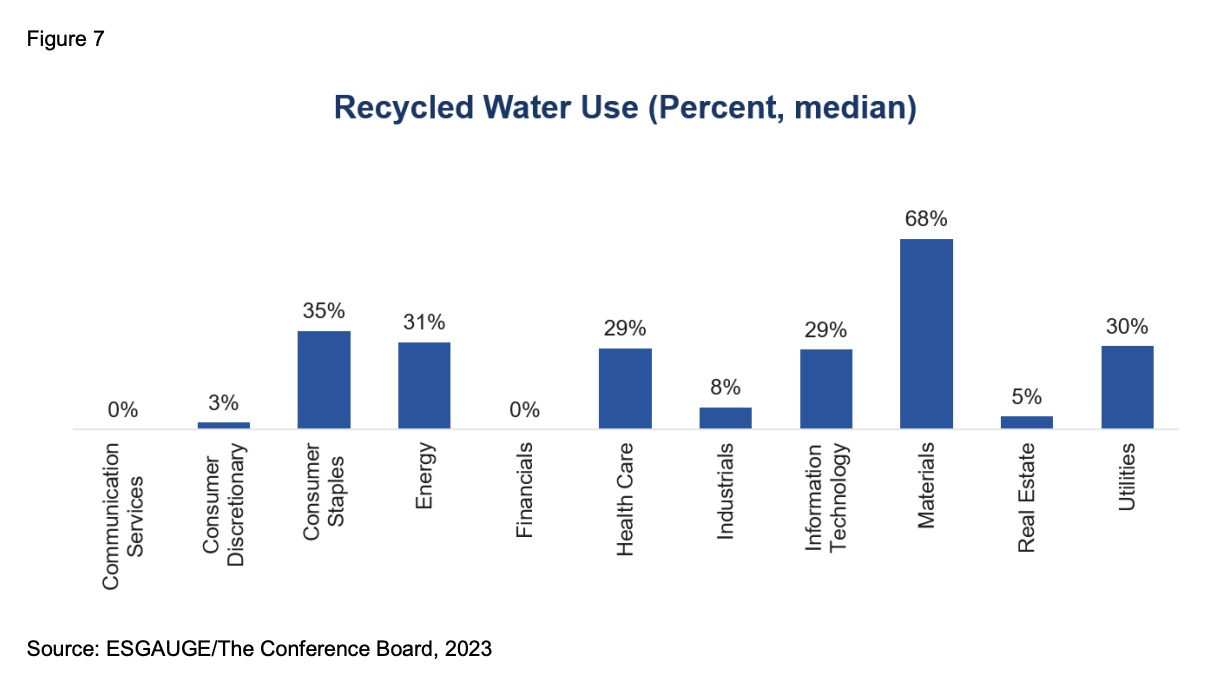

While the utilities sector did not have the highest percentage of recycled water use, in absolute terms it recycled four and a half times more water than all water withdrawn by the other sectors combined. While there is likely some cause and effect on water stress, location appears a key consideration, with relatively low water withdrawals but a high percentage withdrawn from stressed areas by companies in the financial, information technology, industrials, health care, and consumer discretionary sectors.

Water continues to be underpriced and undervalued.[26] Access to water will become an increasingly critical factor for businesses, and as water becomes scarcer, its true value will be realized, increasing costs, and driving water conservation and recycling efforts.[27] Companies should understand not just how much water they use, but where it comes from, and what recycling options are available to mitigate present and future costs. Water scarcity represents a significant cost to business, but environmental nonprofit CDP estimated the cost of inaction to be six and a half times greater—at $92 billion—than that of water scarcity ($14 billion).[28] The SBTN included freshwater quantity and/or quality for direct operations and upstream scope in each basin in its gold-standard methodologies.

The annual survey of C-Suite executives from The Conference Board suggests widespread awareness of the need for businesses to prioritize water as an environmental issue: in 2023, survey participants ranked it fourth among pressing environmental concerns.[29] Research shows that incentivization may be underutilized: the CDP reported 38% of C-Suites are incentivized on water management issues, with 8% of C-Suite incentives related to water management in the supply chain, and 3% of chief procurement officers incentivized on water-related issues.[30] Opportunity therefore exists to implement incentivization programs similar to ESG performance remuneration[31] to drive engagement and effect change throughout a company’s value chain.

A Circular Economy Will Reduce Biodiversity Loss

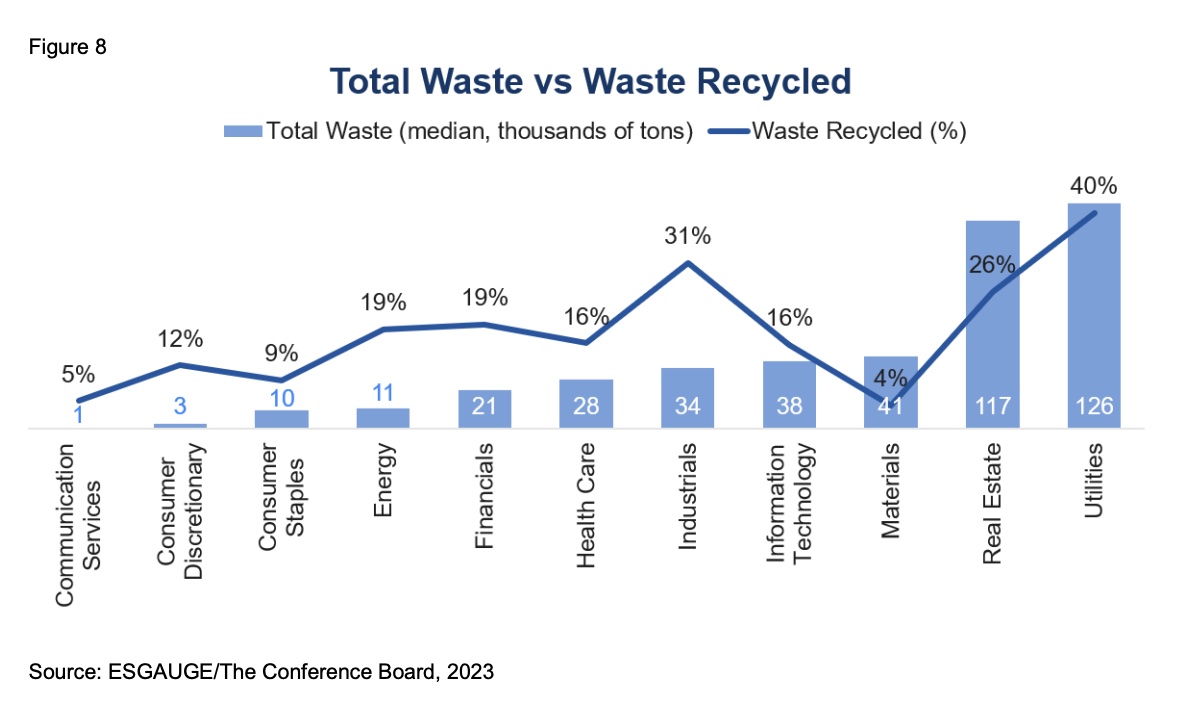

Over 2 billion tons of waste are produced globally each year, a figure that is forecast to grow by 70% by 2050.[32] Electronic waste is the fastest-growing type, and less than 20% of waste is recycled.[33] Generally in 2022, the percentage of waste recycled across sectors increased with the amount of waste produced, except for the information technology and materials sectors, which had proportionally lower recycling rates. The highest recycling rates were by companies in utilities, industrials, and real estate, and the lowest in communication services and consumer staples.

The type of waste produced is as important as the amount, with communication services and materials producing the most hazardous forms of waste. Materials-use disclosures and amounts were generally low, so no trends were seen. This does, however, highlight the need for greater disclosure of materials used to better understand their impact on the environment and biodiversity.

The UN’s International Resource Panel estimated in 2019 that the extraction and processing of natural resources, especially agriculture, accounted for 90% of biodiversity loss. Recycling reduces the need to extract and process more raw materials by keeping materials in use for longer, reducing the demand for primary resources, preventing pollution, and promoting regenerative practices[34] that benefit biodiversity. For example, the practice of recycling metals like copper, steel, and aluminum reduces the need for logging and mining, which have devastating effects on the biodiversity of natural environments. Recycling paper, plastic, and glass has significant energy-saving benefits if one considers how resource intensive the production and disposal of these materials is, and the fact that a reduction in energy consumption translates to lower greenhouse gas emissions and climate change impacts on biodiversity.[35] Ultimately, companies should embrace the circular economy as necessary to reduce biodiversity loss.

Conclusion: What Can Businesses Do Now?

Companies across the economy face risks from the loss of biodiversity but may not be fully aware of this fact. While new regulations will prompt multinational firms to increase attention to this area, there is a powerful incentive for companies to view biodiversity as a key business issue on par with climate change.

- Companies should appreciate the strong business case for biodiversity (which can be at least as strong as the one for addressing climate change). A decrease in biodiversity can expose them to direct risks, including resource scarcity, supply chain disruptions, rising operational costs, liability issues, and the irreversible loss of vital resources or services. Industries from agriculture to travel and tourism depend directly on preserving species, and even more sectors rely on it for their supply chains. Boards and executives should address biodiversity not as an isolated topic, but as part of a suite of related environmental issues.

- Disclosures on biodiversity are growing rapidly, and companies should track what their peers are saying in this area. Some 34% of S&P 500 firms disclosed a biodiversity policy in 2023, up from 18% in 2022. With new EU reporting requirements, companies should prepare to disclose not just their biodiversity policies, but also risks to the company, and the impact of the company and its supply chain on biodiversity.

- Leveraging biodiversity might be an effective way to get boards of directors to focus on climate, especially if they are dependent on naturally produced goods in their supply chain. If the board is overlooking climate issues, highlighting the connection between climate impact and their upstream supply chain via biodiversity may help capture their attention.

- Biodiversity credits are emerging as a strategy to reduce a company’s impact but face even greater challenges than carbon credits. It can be difficult to substitute the loss of a species in one location with growth in another. Companies would be well advised to primarily focus on avoiding the loss of species, rather than finding other ways to compensate for such losses.

- Companies should be prepared to respond to growing pressure from investors and nongovernmental organizations for a comprehensive approach toward environmental impact. In this regard, companies should examine their value chains to identify critical intersections with biodiversity, focusing on areas crucial for their operations.

- Companies should invest in a circular economy business model, which will reduce biodiversity loss. Utilities and real estate, two sectors that face significant risks from biodiversity, are leaders in recycling. More industries should increase recycling to keep materials in use longer, reduce pollution and waste, and promote regenerative practices that benefit biodiversity.

- Companies should seek to use collaboration with stakeholders, including from the upstream and downstream supply chain, as a way of tying their biodiversity objectives to broader societal goals. Companies should begin to set their biodiversity goals as part of their own strategic planning process and reach out to peers and those in their upstream and downstream value chains to see what can be done collectively.

- Companies should prepare for increased water scarcity. Water usage may differ greatly across business sectors. Companies using the most water were in the utilities sector—with the median water withdrawn over 11 times that of all other sectors combined. Companies can begin by understanding how much water they and their value chain use, as well as the sources of that water. This will enable them to implement programs to preserve water and aquatic diversity throughout their value chains.

Methodology and Access to DataThe report discusses the risk of biodiversity loss to businesses, and the current state of reporting on biodiversity. We look at related environmental risks such as water, waste, and legal compliance in the context of recent and upcoming regulatory changes. We also explore the challenges and opportunities that businesses face when addressing environmental risk and scale action for biodiversity. The report is based on an analysis of sustainability reporting metrics by 2,969 companies in the Russell 3000 Index conducted by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE. Data comprising 23 core metrics within biodiversity, waste and recycling, water and effluents were obtained by ESGAUGE from companies’ publicly reported sustainability information—including annual reports, proxy statements, sustainability/CSR reports, and company websites. Comparisons are made with companies in the S&P 500 Index and the S&P MidCap 400. Within the Russell 3000 index, the data analysis is extended to 11 GICS business sectors and 14 company size groups (measured by annual revenue and asset value). Data analysis is complemented with insights from a series of roundtables and focus groups held by The Conference Board on the topic of sustainability disclosure in the course of 2023. The full dataset for this report can be accessed and visualized through an interactive online dashboard available at https://conferenceboard.esgauge.org/environmental |

Endnotes

1World Economic Forum, Nature Risk Taking: Why the Crisis Engulfing Nature Matters for Business and the Economy, January 19, 2020.(go back)

3World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2022, January 2022.(go back)

4UN Convention to Combat Desertification, Global Land Outlook, Second Edition, 2022.(go back)

5World Wildlife Fund, What Is the Sixth Mass Extinction and What Can We Do About It?, 2020.(go back)

6Richard Gray, Sixth Mass Extinction Could Destroy Life as We Know It: Biodiversity Expert, Horizon: the EU Research and Innovation Magazine, European Commission, March 4, 2019.(go back)

7World Wildlife Fund, Living Planet Report 2022, October 2022.(go back)

8United Nations, Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’: Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’, May 2019.(go back)

9Anuj Saush and Ioannis Siskos, Biodiversity Loss: What Does It Mean For Your Business?, The Conference Board, June 2021.(go back)

10Joerg Rueedi and Esther Whieldon, Biodiversity Is Still a Blind Spot for Most Companies Around the World, S&P Global, December 2022.(go back)

11Convention on Biological Diversity, Aichi Biodiversity Targets 2011-2020, 2010.(go back)

12Thomas Singer, Sustainability Reporting Practices 2022: Climate-Risk Disclosures, The Conference Board, January 2022.(go back)

13European Commission, Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, 2020.(go back)

14Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, G7 Backs New Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, June 5, 2021.(go back)

15Anuj Saush and Ioannis Siskos, Biodiversity Loss: What Does It Mean for Your Business?, The Conference Board, June 2021.(go back)

16Science Based Targets Network, The First Corporate Science-Based Targets for Nature, 2023.(go back)

17Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield, The US Touts Support for Biodiversity – But at Cop15, It Remains on the Sidelines, The Guardian, December 17, 2022.(go back)

18Cherie Gray and Akanksha Khatri, How Biodiversity Credits Can Deliver Benefits for Business, Nature, and Local Communities, World Economic Forum, December 9, 2022.(go back)

19Zach St. George, Pricing Nature: Can ‘Biodiversity Credits’ Propel Global Conservation?, Yale Environment 360, April 6, 2023.(go back)

20Ben Elgin et al., Faulty Credits Tarnish Billion-Dollar Carbon Offset Seller, Bloomberg, March 24, 2023; S&P Global, Carbon Capture Removal and Credits Pose Challenges for Companies, Sustainability Insights Research, June 8, 2023.(go back)

21Saush and Siskos, Biodiversity Loss.(go back)

22World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2022, January 11, 2022.(go back)

23Jay Famiglietti and José Iganacio Gallindo, Water Shortages Must Be Placed on the Climate-Change Agenda. This Is Why, World Economic Forum, August 24, 2022.(go back)

24Marvin Clemons, Latest Projection Shows Lake Mead Down About 30 Feet in 2 Years, Las Vegas Journal Review, November 17, 2022.(go back)

25US Department of the Interior, America the Beautiful.(go back)

26UNESCO, Water—One of the Most Undervalued Resources on Earth, April 20, 2023.(go back)

27Alexander Heil, Is Water Running Out?, The Conference Board, May 2023.(go back)

28CDP, Scoping Out: Tracking Nature Across the Supply Chain, March 2023.(go back)

29Chuck Mitchell et al., C-Suite Outlook 2023: On the Edge, The Conference Board, January 2023.(go back)

30CDP, Scoping Out, Id.(go back)

31Steve Newman, Large US Firms Make Meaningful Progress on GHG Emissions, The Conference Board, October 2023.(go back)

32The World Bank, Global Waste to Grow by 70 Percent by 2050 Unless Urgent Action is Taken: World Bank Report, Press Release, September 20, 2018.(go back)

33Bruna Alves, Global Waste Generation—Statistics and Facts, Statistica, August 31, 2023.(go back)

34European Environment Agency, The Benefits to Biodiversity of a Strong Circular Economy, August 15, 2023.(go back)

35US Environmental Protection Agency, Recycling Economic Information Report, 2020.(go back)

Print

Print