Rex Wang Renjie is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Tinbergen Institute; and Shuo Xia is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Halle Institute for Economic Research and Leipzig University. This post is based on their paper. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Why Firms Adopt Antitakeover Arrangements by Lucian A. Bebchuk; Toward a Constitutional Review of the Poison Pill (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk and Robert J. Jackson, Jr.; and What Matters in Corporate Governance? (discussed on the Forum here) by Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Allen Ferrell.

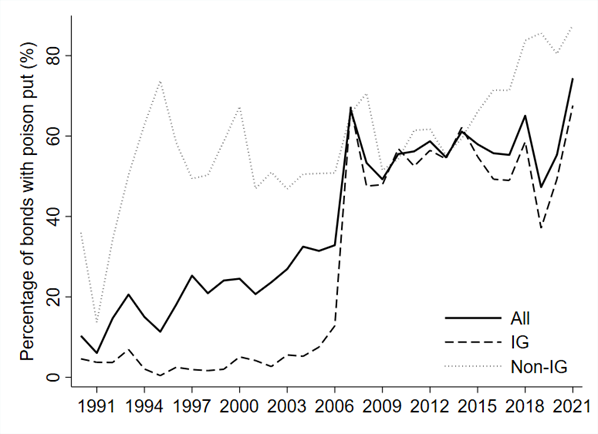

Corporate bonds with a poison put covenant, which we refer to as “poison bonds”, first appeared during the hostile takeover wave in the 1980s. A poison put covenant grants bondholders the right to demand immediate repayment of the bond in a change-of-control event. Originally designed to protect bondholders from potential wealth transfer following leveraged buyouts, this covenant soon became an effective takeover defense strategy, primarily used by high-yield issuers in the 80’s and 90’s (Billett, Jiang, and Lie, 2010). However, a significant shift has occurred in this market since the mid-2000s. As shown in Figure 1, the fraction of poison bonds among new issues increased substantially around 2005, predominantly driven by investment-grade (IG) issues. Before 2005, poison bonds accounted for less than 10% of IG issues, but after 2005, they represented over 60% of all new IG issues. In our paper, we investigate the cause behind this trend and examine its impact on shareholder value.

Figure 1

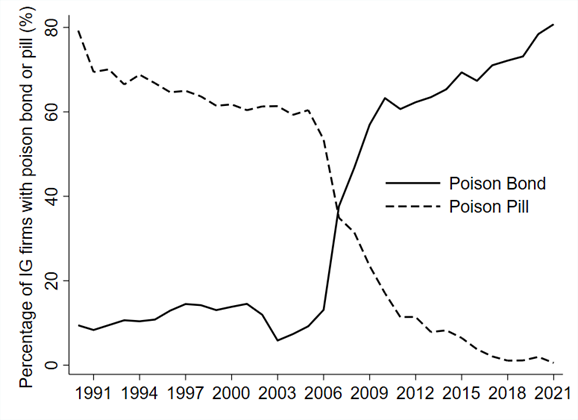

We show that this recent surge in poison bonds has been driven by the persistent pressure to eliminate poison pills over the past two decades. As one of the most effective anti-takeover provisions, poison pills have been criticized for entrenching managers and destroying shareholder value (e.g., Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell, 2008). This view has fueled an increasing pressure on public companies to rescind poison pills. In December 2004, the Institutional Investor Service (ISS) even announced a recommendation to oppose boards adopting or renewing poison pills without shareholder approval. As a result of such governance reform efforts, poison pill usage among large firms dropped significantly from 55% in 2004 to just 2% in 2021 (Karpoff and Wittry, 2023).

We find a compelling inverse relationship between poison pills and poison bonds, as illustrated in Figure 2. In particular, between 2004 and 2010, when the prevalence of poison pills among IG firms declined the most, from 59% to 17%, the percentage of IG firms with an outstanding poison bond rose sharply, from 7% to 63%. This trend is also observable, though less pronounced, among non-IG firms. Our formal empirical analysis ensures that this relationship is not driven by any observable firm characteristics, macroeconomic or industry-wide shocks, or firm-specific time-invariant unobserved factors that might influence poison bond issuance decisions.

Figure 2

To be clear, we are not claiming that firms with poison bonds would never use poison pills again. Firms might still adopt poison pills when facing a hostile takeover, as evidenced recently by Twitter’s reaction to Elon Musk’s unsolicited bid. However, our point is that the prevailing aversion of shareholders towards poison pills has led firms to explore alternatives, and consequently, poison bonds have gained a surge in popularity.

To further sharpen the causal interpretation of the link between poison bonds and poison pills, we employ a regression discontinuity design that exploits voting outcomes in the narrow interval around the majority threshold, which generates a plausibly exogenous variation in poison pill adoption and removal. Using hundreds of proposals related to poison pills, we find that passing a proposal against poison pills at the majority threshold significantly increases the firm’s likelihood of issuing a poison bond in the subsequent year, from 0% to 12.5%.

Having established the causal link between poison pills and poison bonds, we proceed to investigate who demands poison put covenants. Specifically, we test whether it is bondholders seeking protection through poison puts or if it is managers issuing poison bonds for entrenchment purposes. Our findings strongly support the latter hypothesis. Among other things, we find that firms actually incur a higher financing cost when they issue poison bonds to replace poison pills. This is consistent with the notion that entrenched managers use poison bonds to protect themselves and need to compensate for the increased managerial agency costs borne by bondholders.

How does this practice impact shareholder value? During the 7-day window around the issuance date, poison bonds are associated with 26 basis points (bps) lower stock returns than other bonds. If the issuing firm has recently removed a poison pill, shareholders lose an additional 62 bps. Notably, this negative shareholder reaction only shows up for issues after mid-2000s. Furthermore, a portfolio strategy that holds firms issuing poison bonds after removing poison pills earns negative abnormal returns ranging from −5.1% to −7.3% per year, suggesting a significant destruction of shareholder value.

Finally, we provide evidence that poison bonds allow managers to engage in empire building. We show an increased likelihood that firms announce large and diversified takeovers following the issuance of poison bonds. These takeovers are more likely to yield negative announcement returns, implying that they may serve the self-interests of managers rather than being optimal investment decisions for shareholders. This relationship is again more pronounced if we focus on firms that replace poison pills with poison bonds.

In sum, we show that the pressure to eliminate poison pills has led firms to issue poison bonds as an alternative strategy since the mid-2000s. This practice entrenches managers and thereby destroys shareholder value. These findings have important implications for the agency theory of debt. On the one hand, the potential agency benefits of debt in addressing the free cash flow problem may be limited when managers exploit debt covenants for entrenchment. On the other hand, the managerial entrenchment facilitated by bond covenants can lead to shareholder-creditor agency conflicts, even in the absence of financial distress. Thus, our study sheds new light on the three-way agency conflicts among shareholders, managers, and creditors.

Print

Print