Merel Spierings is Senior Researcher at The Conference Board ESG Center in New York. This post relates to a report authored by Ms. Spierings and based on disclosure data from Corporate Board Practices in the Russell 3000, S&P 500, and S&P MidCap 400: Live Dashboard, a live online dashboard published by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with Debevoise & Plimpton, the KPMG Board Leadership Center, Russell Reynolds Associates, and The John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware.

This report completes a series on Corporate Board Practices in the Russell 3000 and S&P 500 and discusses areas of board governance that often receive less investor and public attention than topics such as board diversity but are nonetheless critical for board excellence. They include director orientation and continuing education, performance evaluations, committee member rotation, and overboarding.

Director Orientation and Ongoing Education

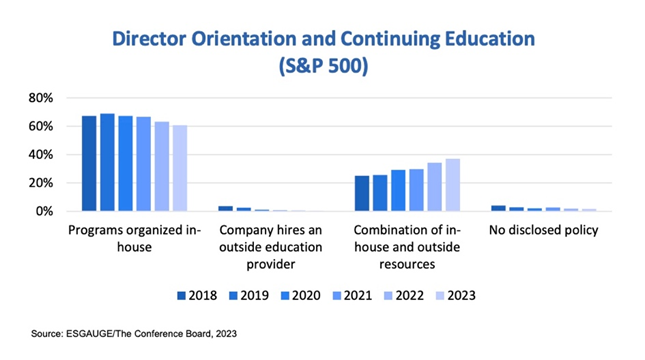

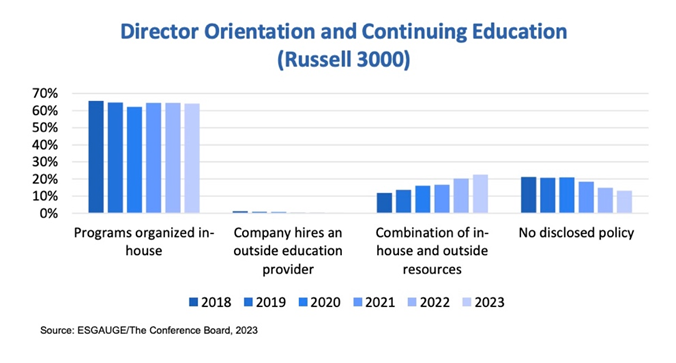

While most US public companies rely exclusively on in-house board education programs, the share of companies complementing internal programs with external resources is increasing. As of November 2023, 37% of S&P 500 companies disclosed relying on a combination of in-house and outside programs to educate new and sitting directors, up from 25% in 2018. During that time frame, the share of S&P 500 companies organizing educational programs exclusively in-house declined (from 67% in 2018 to 61% in 2023). The Russell 3000 has seen a similar pattern, with a rise of companies using internal and external resources (from 12% in 2018 to 23% in 2023) and a decline in companies relying solely on internal programs (from 66% in 2018 to 64% in 2023).

Management bears much of the responsibility for ensuring that the board is fluent in areas that are relevant to the company’s business and business strategy. Currently, however, management itself sees significant gaps in board knowledge.[1] As boards are addressing an array of topics—ranging from AI to climate change to supply chain resilience—companies should consider enlisting the assistance of outside expertise in providing relevant educational programs for the board to complement management’s knowledge of the company. At the same time, the board can ask for presentations on areas where it wants additional information. Exposing the board to diversity of thought, whether from within or outside the organization, can enhance its ability to make informed decisions, adapt to changing circumstances, and avoid institutional groupthink.

As part of this process, management will want to ensure it has sufficient informal interactions with the board and individual directors, so it can identify and address any gaps between what the board knows (which might be more than management realizes) and what it should know.

Board and Director Performance Evaluations

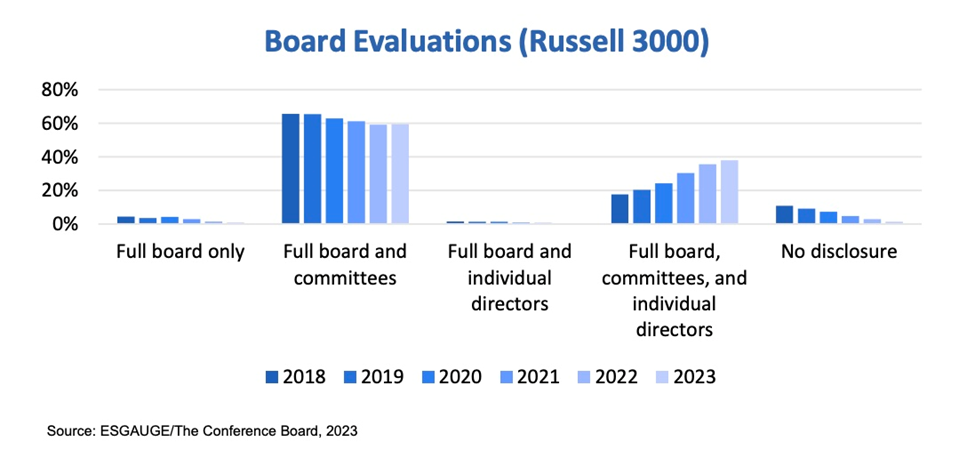

Incorporating individual director evaluations into the annual board self-assessment is now a common practice among larger companies. As of November 2023, a majority (56%) of S&P 500 disclosed conducting a combination of full board, committee, and individual director evaluations (including both peer assessments and self-assessments), up from 37% in 2018. In that index, the practice of conducting only board and committee evaluations has declined from 58% in 2018 to 48% in 2023. The Russell 3000 has also seen a rise in full board, committee, and individual evaluations (from 18% in 2018 to 38% in 2023), but 50% of companies continue to conduct only full board and committee evaluations (down from 65% in 2018).

Board and committee evaluations can benefit from a multifaceted approach that incorporates both surveys and the nuanced insights gathered through interviews with individual directors. Collective discussions during board and committee meetings can further enrich the evaluation process by addressing the results of the self-assessments and creating action plans for the issues raised.

Furthermore, conducting individual director evaluations (every two or three years) along with traditional annual board and committee evaluations can be helpful, as it provides detailed insights into individual performance; identifies strengths, opportunities, and skill gaps; and enables the formulation of targeted development plans. This approach strengthens accountability and can lead to changes in board composition, resulting in a well-rounded board that has critical competencies for long-term performance and the ability to navigate the complexities of the current business environment.[2] In between formal evaluation cycles, management should take note of which directors are engaged, ask probing questions, and effectively challenge management—and which ones don’t. Management should bring this to the attention of board leadership, so issues around individual director performance can be addressed informally on an ongoing basis. These are sensitive discussions and require a strong level of trust between management and board leadership.

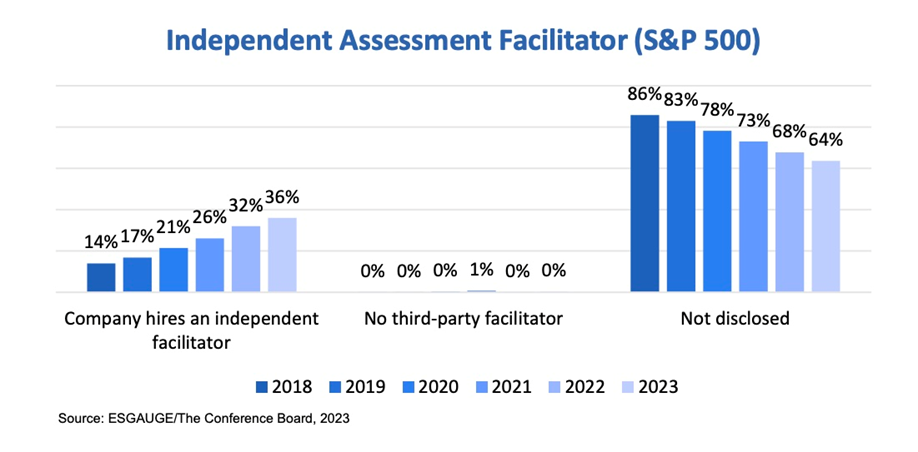

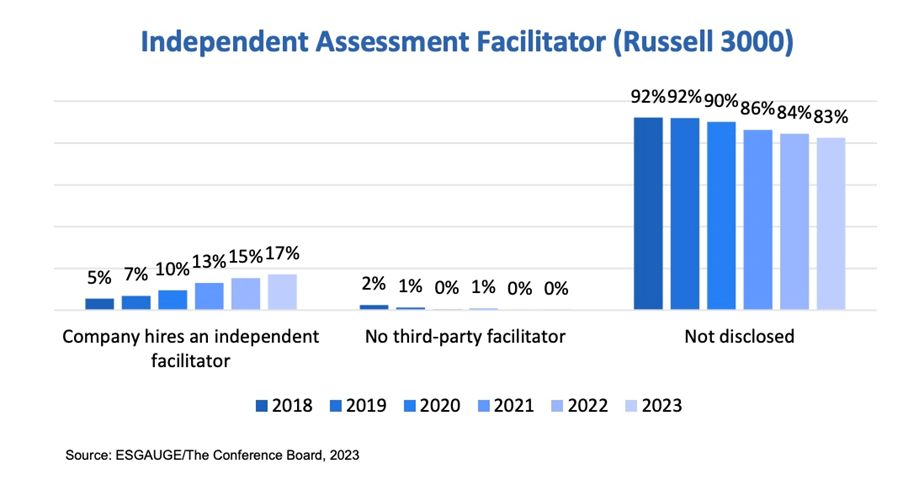

Companies increasingly disclose hiring an independent facilitator for board evaluations, with larger companies being more inclined to disclose their use of an independent facilitator compared to their smaller counterparts. As of November 2023, 36% of S&P 500 companies and 17% of Russell 3000 firms disclosed using an independent facilitator for board evaluations versus 14% of S&P 500 and 5% of Russell 3000 companies in 2018.![]()

Hiring an independent facilitator for board evaluations can be beneficial. Directors may feel more comfortable providing candid feedback, and an independent facilitator may also be better equipped to benchmark the board’s performance against external standards and best practices, as well as identify areas for improvement. However, as our discussions with leading governance professionals revealed, companies don’t need to hire outside facilitators every year. Engaging them every few years not only prevents the erosion of trust among directors but can also balance the benefits of external expertise with practical considerations (e.g., resource efficiency and meaningful implementation of changes based on the evaluation results). Importantly, when engaging an independent facilitator, the company ultimately bears the responsibility for safeguarding legal privilege and ensuring an environment conducive to open and honest feedback.

Director Overboarding Policies

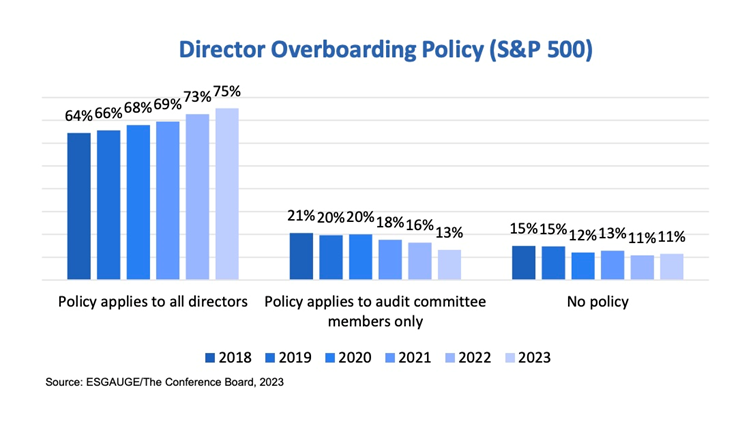

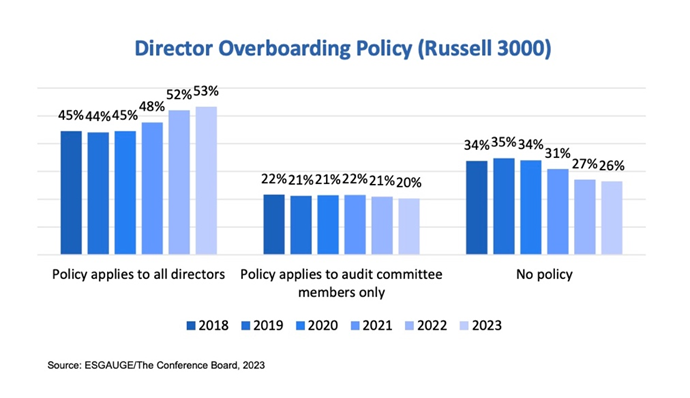

A majority of US public companies now have director overboarding policies. In the S&P 500, the share of companies with an overboarding policy applicable to all directors grew from 64% in 2018 to 75% as of November 2023, and from 45% to 53% in the Russell 3000.

Director overboarding policies help ensure that directors can devote sufficient time and attention to the growing array of board responsibilities, which in turn can enhance board performance and engagement. Such policies can also promote board refreshment by prompting a dialogue with board members as to whether the director should resign from a particular board.

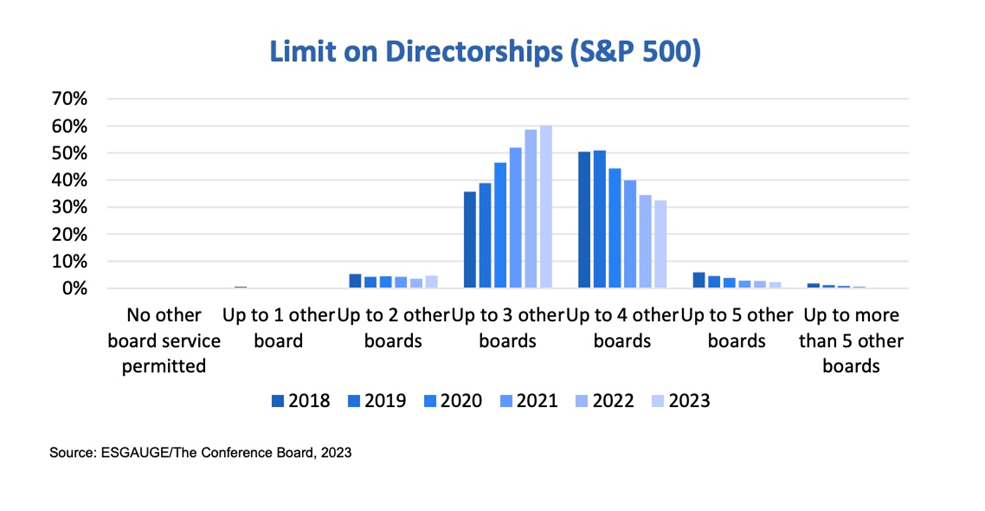

When an overboarding policy for all directors exists, it typically sets a limit of three additional board seats. As of November 2023, 60% of S&P 500 companies and 49% of Russell 3000 firms with an overboarding policy for all directors restricted additional board services to three seats. That is a notable increase from five years ago, when 36% of the S&P 500 and 33% of the Russell 3000 with such policies set the limit at three other directorships.

In this context, “all directors” refers to independent, nonexecutive directors. More stringent limits (i.e., a limit of one additional board seat) generally apply to directors who are also a public company CEO or executive officer.

Meanwhile, 33% of S&P 500 and 38% of Russell 3000 companies with director overboarding policies set the limit even higher, at four seats. However, those percentages have declined in the past five years, by 17 percentage points from 50% in the S&P 500 and 7 percentage points from 45% in the Russell 3000.

While companies are moving in the direction of setting a policy limit of three additional board seats, in practice that can still result in overboarding, depending on the circumstances at the companies at which the directors serve. Moreover, while adopting an overboarding policy can be useful, it is more important for boards to have candid conversations about their evolving time requirements and the ability of directors to devote the time necessary to the role. For example, in its Summary of Material Changes to State Street Global Advisors’ 2023 Proxy Voting and Engagement Guidelines, State Street indicates that starting in 2024 for companies in the S&P 500, it will no longer use numerical limits to identify overcommitted directors and instead “require that companies themselves address this issue in their internal policy on director time commitments and that the policy be publicly disclosed.” By doing so, State Street expects to see increased transparency over how nominating committees assess their directors’ time commitments and what factors are included in this discussion.

Board Committee Member Rotations

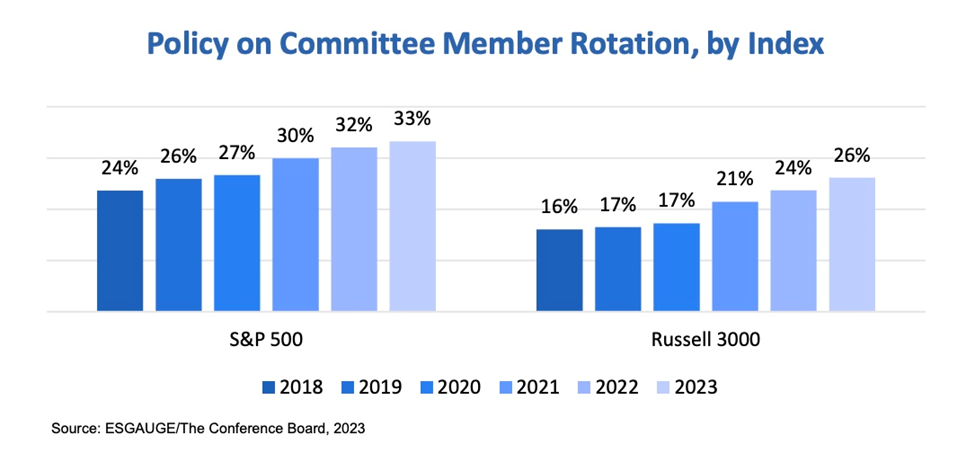

There has been an increase in companies adopting policies on committee member rotation. Thirty-three percent of S&P 500 and 26% of Russell 3000 companies now have such a policy, which may include elements such as term limits, rotation criteria, the reappointment process, and exceptions compared to 24% and 16%, respectively in 2018. Additionally, of those companies that disclose having term limits for committee members (9% of S&P 500 and 6% of Russell 3000 companies in 2023), most are currently set to five terms.

Companies can use committee member rotation and committee term limits as part of board education. Serving on different committees allows directors to gain a more comprehensive view of the company. Additionally, committee member rotation brings new individuals with fresh and diverse perspectives to committee roles. It can also facilitate the sharing of knowledge and expertise across the board and contribute to positive board dynamics by promoting a sense of equal opportunity to serve on committees and in leadership positions.

Conclusion

- Boards should consider increasing their use of external resources for board education programs. The number of S&P 500 boards relying to some extent on external educational resources has increased significantly in the past five years. Enlisting third-party experts, especially when their presentations are tailored to address a company’s particular circumstances, can be an efficient and objective way to increase board fluency in key areas where the board may not have deep experience, such as the digital and sustainability transformations of the business, and other areas as needed.

- As part of the evaluation process, boards should consider including, at least on a periodic basis, evaluating the performance of individual directors and retaining an external facilitator. Over half of S&P 500 companies now conduct individual director assessments, up from approximately one-third five years ago. As boards move beyond a traditional independent oversight role to become more engaged, strategic thought partners for management, board evaluations should be thoughtful, thorough, and nuanced.

- In light of expanding workloads, boards should take a fresh look at the time commitments expected of directors and, if they haven’t already done so, consider adopting policies that address the number of boards on which directors can serve. Overboarding policies are now a predominant practice, embraced by three-quarters of the S&P 500 and over half the Russell 3000 and supported by the proxy advisory firms. But policies alone are insufficient. As part of the annual evaluation process, directors should assess their ability, both on an individual and collective level, to dedicate the necessary time to fulfill their responsibilities effectively and make informed decisions.

- Boards should consider adopting a policy on rotating committee memberships as a way to support board education and excellence. A growing minority of companies have adopted guidelines on rotating committee leadership and/or membership positions. A measured pace of turnover on committees can deepen directors’ understanding of the company, support cross-committee collaboration, and bring fresh perspectives to committee discussions.

Methodology and Access to Live DataThis report documents current practices adopted by US publicly traded companies to promote board excellence—including director orientation and continuing education, performance evaluations, committee member rotation, and overboarding. The analysis is based on recently filed proxy statements and complemented by the review of organizational documents (including articles of incorporation, bylaws, corporate governance principles, board committee charters, and other corporate policies made available in the Investor Relations section of companies’ websites). The data for 2023 are as of November 10, 2023, and are based on disclosures made by 2699 companies in the Russell 3000 and 457 in the S&P 500. The report also presents key insights gained during a Focus Group discussion with in-house governance leaders. The project is conducted by The Conference Board and ESG data analytics firm ESGAUGE, in collaboration with Debevoise & Plimpton, the KPMG Board Leadership Center, Russell Reynolds Associates, and the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. Data discussed in this report can be accessed and visualized through an interactive online dashboard at http://conferenceboard.esgauge.org/boardpractices |

Endnotes

1See the findings of a survey of more than 600 C-Suite executives at US publicly traded companies discussed in Board Effectiveness: A Survey of the C-Suite, The Conference Board-PwC, Research Report, May 18, 2023.(go back)

2Merel Spierings, Taking a Long-Term Approach to Board Composition, The Conference Board, Research Report, September 25, 2023.(go back)

Print

Print