This post provides the text of the post-trial opinion regarding the case between Richard J. Tornetta on behalf of Tesla, Inc. against Elon Musk, decided by the Delaware Court of Chancery on January 30, 2024. This post is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

RICHARD J. TORNETTA, Individually

and on Behalf of All Others Similarly

Situated and Derivatively on Behalf of

Nominal Defendant TESLA, INC.,

Plaintiff,

v.

ELON MUSK, ROBYN M. DENHOLM,

ANTONIO J. GRACIAS, JAMES

MURDOCH, LINDA JOHNSON RICE,

BRAD W. BUSS, and IRA

EHRENPREIS,

Defendants, and

TESLA, INC., a Delaware Corporation,

Nominal Defendant.

POST-TRIAL OPINION

Date Submitted: April 25, 2023

Date Decided: January 30, 2024

Gregory V. Varallo, Glenn R. McGillivray, BERNSTEIN LITOWITZ BERGER & GROSSMANN LLP, Wilmington, Delaware; Jeroen van Kwawegen, Margaret Sanborn-Lowing, BERNSTEIN LITOWITZ BERGER & GROSSMANN LLP, New York, New York; Peter B. Andrews, Craig J. Springer, David M. Sborz, Andrew J. Peach, Jackson E. Warren, ANDREWS & SPRINGER LLC, Wilmington, Delaware; Jeremy S. Friedman, Spencer M. Oster, David F.E. Tejtel, FRIEDMAN OSTER & TEJTEL PLLC; Bedford Hills, New York; Counsel for Plaintiff Richard J. Tornetta.

David E. Ross, Garrett B. Moritz, Thomas C. Mandracchia, ROSS ARONSTAM & MORITZ LLP, Wilmington, Delaware; Evan R. Chesler, Daniel Slifkin, Vanessa A. Lavely, CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP, New York, New York; Counsel for Defendants Elon Musk, Robyn M. Denholm, Antonio J. Gracias, James Murdoch, Linda Johnson Rice, Brad W. Buss, and Ira Ehrenpreis.

Catherine A. Gaul, Randall J. Teti, ASHBY & GEDDES, P.A., Wilmington, Delaware; Counsel for Nominal Defendant Tesla, Inc.

McCORMICK, C.

Was the richest person in the world overpaid? The stockholder plaintiff in this derivative lawsuit says so. He claims that Tesla, Inc.’s directors breached their fiduciary duties by awarding Elon Musk a performance-based equity-compensation plan. The plan offers Musk the opportunity to secure 12 total tranches of options, each representing 1% of Tesla’s total outstanding shares as of January 21, 2018. For a tranche to vest, Tesla’s market capitalization must increase by $50 billion and Tesla must achieve either an adjusted EBITDA target or a revenue target in four consecutive fiscal quarters. With a $55.8 billion maximum value and $2.6 billion grant date fair value, the plan is the largest potential compensation opportunity ever observed in public markets by multiple orders of magnitude—250 times larger than the contemporaneous median peer compensation plan and over 33 times larger than the plan’s closest comparison, which was Musk’s prior compensation plan. This post-trial decision enters judgment for the plaintiff, finding that the compensation plan is subject to review under the entire fairness standard, the defendants bore the burden of proving that the compensation plan was fair, and they failed to meet their burden.

A board of director’s decision on how much to pay a company’s chief executive officer is the quintessential business determination subject to great judicial deference. But Delaware law recognizes unique risks inherent in a corporation’s transactions with its controlling stockholder. Given those risks, under Delaware law, the presumptive standard of review for conflicted-controller transactions is entire fairness. To invoke the entire fairness standard, the plaintiff argues that Musk’s compensation plan was a conflicted-controller transaction. The plaintiff thus forces the question: Does Musk control Tesla?

Delaware courts have been presented with this question thrice before, when more adroit judges found ways to avoid definitively resolving it. This decision dares to “boldly go where no man has gone before,” or at least where no Delaware court has tread. The collection of features characterizing Musk’s relationship with Tesla and its directors gave him enormous influence over Tesla. In addition to his 21.9% equity stake, Musk was the paradigmatic “Superstar CEO,” who held some of the most influential corporate positions (CEO, Chair, and founder), enjoyed thick ties with the directors tasked with negotiating on behalf of Tesla, and dominated the process that led to board approval of his compensation plan. At least as to this transaction, Musk controlled Tesla.

The primary consequence of this finding is that the defendants bore the burden of proving at trial that the compensation plan was entirely fair. Delaware law allows defendants to shift the burden of proof under the entire fairness standard where the transaction was approved by a fully informed vote of the majority of the minority stockholders. And here, Tesla conditioned the compensation plan on a majority-of-the-minority vote. But the defendants were unable to prove that the stockholder vote was fully informed because the proxy statement inaccurately described key directors as independent and misleadingly omitted details about the process.

The defendants were thus left with the unenviable task of proving the fairness of the largest potential compensation plan in the history of public markets. If any set of attorneys could have achieved victory in these unlikely circumstances, it was the talented defense attorneys here. But the task proved too tall an order.

The concept of fairness calls for a holistic analysis that takes into consideration two basic issues: process and price. The process leading to the approval of Musk’s compensation plan was deeply flawed. Musk had extensive ties with the persons tasked with negotiating on Tesla’s behalf. He had a 15-year relationship with the compensation committee chair, Ira Ehrenpreis. The other compensation committee member placed on the working group, Antonio Gracias, had business relationships with Musk dating back over 20 years, as well as the sort of personal relationship that had him vacationing with Musk’s family on a regular basis. The working group included management members who were beholden to Musk, such as General Counsel Todd Maron who was Musk’s former divorce attorney and whose admiration for Musk moved him to tears during his deposition. In fact, Maron was a primary go-between Musk and the committee, and it is unclear on whose side Maron viewed himself. Yet many of the documents cited by the defendants as proof of a fair process were drafted by Maron.

Given the collection of people tasked with negotiating on Tesla’s behalf, it is unsurprising that there was no meaningful negotiation over any of the terms of the plan. Ehrenpreis testified that he did not view the negotiation as an adversarial process. He said: “We were not on different sides of things.” Maron explained that he viewed the process as “cooperative” with Musk. Gracias admitted that there was no “positional negotiation.” This testimony came as close to admitting a controlled mindset as it gets. And consistent with this specific-to-Musk approach, the committee avoided using objective benchmarking data that would have revealed the unprecedented nature of the compensation plan.

In credit to these witnesses, their testimony was truthful. They did not take a position “on the other side” of Musk. It was a cooperative venture. There were no positional negotiations. Musk proposed a grant size and structure, and that proposal supplied the terms considered by the compensation committee and the board until Musk unilaterally lowered his ask six months later. Musk did not seem to care much about the other details. They got ironed out.

In this litigation, the defendants touted as concessions certain features of the compensation plan—a five-year holding period, an M&A adjustment, and a 12- tranche structure that required Tesla to increase market capitalization by $100 billion more than Musk had initially proposed to maximize compensation under the plan. But the holding period was adopted in part to increase the discount on the publicly disclosed grant price, the M&A adjustment was industry standard, and the 12-tranche structure was reached in an effort to translate Musk’s fully-diluted-share proposal to the board’s preferred total-outstanding-shares metric. It is not accurate to refer to these terms as concessions.

The defendants also point to the duration of the process (nine months) and the number of board and committee meetings (ten) as evidence that the process was thorough and extensive. The defendants’ statistics, however, elide the lack of substantive work. Time spent only matters when well spent. Plus, most of the work on the compensation plan occurred during small segments of those nine months and under significant time pressure imposed by Musk. Musk dictated the timing of the process, making last-minute changes to the timeline or altering substantive terms immediately prior to six out of the ten board or compensation committee meetings during which the plan was discussed.

And that is just the process. The price was no better. In defense of the historically unprecedented compensation plan, the defendants urged the court to compare what Tesla “gave” against what Tesla “got.” This structure set up the defendants’ argument that the compensation plan was “all upside” for the stockholders. The defendants asserted that the board’s primary objective with the compensation plan was to position Tesla to achieve transformative growth, and that Tesla accomplished this by securing Musk’s continued leadership. The defendants offered Musk an opportunity to increase his Tesla ownership by about 6% (from about 21.9% to at most 28.3%) if, and only if, he increased Tesla’s market capitalization from approximately $50 billion to $650 billion, while also hitting the operational milestones tied to Tesla’s top-line (revenue) or bottom-line (adjusted EBITDA) growth. According to the defendants, the deal was “6% for $600 billion of growth in stockholder value.”

At a high level, the “6% for $600 billion” argument has a lot of appeal. But that appeal quickly fades when one remembers that Musk owned 21.9% of Tesla when the board approved his compensation plan. This ownership stake gave him every incentive to push Tesla to levels of transformative growth—Musk stood to gain over $10 billion for every $50 billion in market capitalization increase. Musk had no intention of leaving Tesla, and he made that clear at the outset of the process and throughout this litigation. Moreover, the compensation plan was not conditioned on Musk devoting any set amount of time to Tesla because the board never proposed such a term. Swept up by the rhetoric of “all upside,” or perhaps starry eyed by Musk’s superstar appeal, the board never asked the $55.8 billion question: Was the plan even necessary for Tesla to retain Musk and achieve its goals?

This question looms large in the price analysis, making each of the defendants’ efforts to prove fair price seem trivial. The defendants proved that Musk was uniquely motivated by ambitious goals and that Tesla desperately needed Musk to succeed in its next stage of development, but these facts do not justify the largest compensation plan in the history of public markets. The defendants argued the milestones that Musk had to meet to receive equity under the package were ambitious and difficult to achieve, but they failed to prove this point. The defendants maintained that the plan is an exceptional deal when compared to private equity compensation plans, but they did not explain why anyone would compare a public company’s compensation plan with a private-equity compensation plan. The defendants insisted that the plan worked in that it delivered to stockholders all that was promised, but they made no effort to prove causation. They also made no effort to explain the rationale behind giving Musk 1% per tranche, as opposed to some lesser portion of the increased value. None of these arguments add up to a fair price.

In the final analysis, Musk launched a self-driving process, recalibrating the speed and direction along the way as he saw fit. The process arrived at an unfair price. And through this litigation, the plaintiff requests a recall.

The plaintiff asks the court to rescind Musk’s compensation plan. The plaintiff’s lead argument is that the court must rescind the compensation plan due to disclosure deficiencies because the plan was conditioned on stockholder approval. This argument, although elegant in its simplicity, is overly rigid and wrong. The plaintiff offers no legal authority for why rescission must automatically follow from an uninformed vote. Generally, a court of equity enjoys broad discretion in fashioning remedies for fiduciary breach, and that general principle applies here.

Although rescission does not automatically result from the disclosure deficiencies, it is nevertheless an available remedy. The Delaware Supreme Court has referred to recission as the “preferrable” (but not the exclusive) remedy for breaches of fiduciary duty when rescission can restore the parties to the position they occupied before the challenged transaction. Rescission can achieve that result in this case, where no third-party interests are implicated, and the entire compensation plan sits unexercised and undisturbed. In these circumstances, the preferred remedy is the best one. The plaintiff is entitled to rescission.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

Trial took place over five days. The record comprises 1,704 trial exhibits, live testimony from nine fact and four expert witnesses, video testimony from three fact witnesses, deposition testimony from 23 fact and five expert witnesses, and 255 stipulations of fact. These are the facts as the court finds them after trial.

A. Tesla And Its Visionary Leader

Tesla is a vertically integrated clean-energy company. Tesla and its employees “design, develop, manufacture, sell and lease high-performance fully electric vehicles and energy generation and storage systems.” As of December 31, 2021, Tesla and its subsidiaries had nearly 100,000 full-time employees worldwide,8 and its market capitalization was over $1 trillion.

Tesla’s success came relatively recently and, by all accounts, was made possible by Musk. In 2004, Musk led Tesla’s Series A financing round, investing $6.5 million. He would invest considerably more before the company went public, take on the role of chairman of Tesla’s Board of Directors (the “Board”) (from April 2004 to November 2018), and, ultimately, become Tesla’s CEO (since October 2008). Musk possesses the ability to “dr[aw] others into his vision of the possible” and “inspir[e] . . . his workers to achieve the improbable.” And although Musk was not at the helm of Tesla at its inception, he became the driving visionary responsible for Tesla’s growth. He earned the title “founder.”

1. The Master Plan

At the time of Musk’s initial investment, Tesla was a small-scale startup producing small quantities of a single vehicle: the Tesla “Roadster,” a high-end, battery-powered sports car. By 2006, however, Tesla had broadened its goals. That year, then-chairman Musk published on Tesla’s blog “The Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan” (a.k.a., the “Master Plan”), which provided a roadmap for Tesla’s future. Distilled, Musk’s vision was to start by building the Roadster sports car, to use “that money to build an affordable car,” to use “that money to build an even more affordable car,” and to “provide zero emission electric power generation options” while accomplishing these production milestones. The plan advanced what Musk described as Tesla’s “overarching purpose”—to move toward a sustainable energy economy, or, as he wrote at the time, to “expedite the move from a mine-and-burn hydrocarbon economy towards a solar electric economy.”

The Master Plan was bold. Although it might seem difficult to believe now, back then, the market for electric vehicles was unproven. Electric-vehicle technology was “described as impossible.” Even traditional automotive startups faced an “incredibly challenging” environment in which many failed. In fact, no new domestic car company since Chrysler in the 1920s had achieved financial success. Given the risks, Musk himself viewed the probability of Tesla completing the Master Plan as “extremely unlikely.”

To even Musk’s surprise, the Master Plan came to fruition. In abbreviated form, the events played out like this: In 2006, Tesla announced that it would begin to sell the Signature 100 Roadster for approximately $100,000. By August 2007, Tesla had pre-sold 570 Roadsters, which became available in 2008, the same year that Musk became Tesla’s CEO. Tesla went public in January 2010, raising $226.1 million. In June 2012, Tesla launched the Model S, delivering 2,650 vehicles by year’s end. Model S sales increased to approximately 22,000 in 2013, 32,000 in 2014, and 50,000 in 2015. Over this period, Tesla developed stationary energy storage products for commercial and residential use, which it began selling in 2013. In 2014, Tesla announced its intent to build its first battery “Gigafactory” and work with suppliers to integrate battery precursor material. The factory went live in 2015. In September 2015, Tesla launched the Model X, a midsize SUV crossover.

2. The Master Plan, Part Deux

By 2016, Tesla had reached the final phase of the Master Plan, and Musk began contemplating the next chapter of Tesla’s development. In July 2016, he published a new strategic document: “Master Plan, Part Deux” (a.k.a., “Part Deux”).

That year, Tesla unveiled a long-range, compact sedan called the “Model 3.” Tesla projected that it would begin mass production of the Model 3 in 2017. That endeavor proved the crucible for Tesla. As the company disclosed on March 1, 2017: “Future business depends in large part on our ability to execute on our plans to develop, manufacture, market and sell the Model 3 vehicle . . . .” Tesla announced another ambitious deadline, stating that its goal was “to achieve volume production and deliveries of this vehicle in the second half of 2017.”

No one thought Tesla could mass produce the Model 3. Musk stated in Part Deux that, “[a]s of 2016, the number of American car companies that haven’t gone bankrupt is a grand total of two: Ford and Tesla.” Tesla had come close to bankruptcy in its early years. And as of March 2017, approximately 20% of Tesla’s total outstanding shares were sold short, making it the most shorted company in U.S. capital markets at that time. Everyone was betting against Tesla and the man at its helm.

3. Musk’s Backstory And Motivations

Musk is no stranger to a challenge, having led the life of a serial entrepreneur. He and his brother, Kimbal Musk, launched Musk’s first start-up in 1995. Musk later co-founded an electronic payment system called X.com, which would be acquired and renamed PayPal. He also founded: in 2002, a rocket development and launch company, Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (“SpaceX”); in 2015, an artificial intelligence research organization, OpenAI Inc.; in 2016, a neurotechnology company, Neuralink Corp.; and, in 2017, a private tunnel-boring company, The Boring Company.

In 2017 through 2018, in addition to his positions at Tesla, Musk was the CEO, CTO, and board chairman of SpaceX and the board co-chair of OpenAI. Musk divided most of his time between SpaceX and Tesla as of June 2017, but he increased the amount of time he spent at Tesla by the end of 2017.

Musk is motivated by ambitious goals, the loftiest of which is to save humanity. Musk fears that artificial intelligence could either reduce humanity to “the equivalent of a house cat” or wipe out the human race entirely. Musk views space colonization as a means to save humanity from this existential threat. Musk seeks to make life “multiplanetary” by colonizing Mars. Reasonable minds can debate the virtues and consequences of longtermist beliefs like those held by Musk, but they are not on trial. What is relevant here is that Musk genuinely holds those beliefs.

Colonizing Mars is an expensive endeavor. Musk believes he has a moral obligation to direct his wealth toward that goal, and Musk views his compensation from Tesla as a means of bankrolling that mission. Musk sees working at Tesla as worthy of his time only if that work generates “additional economic resources . . . that could . . . be applied to making life multi-planetary.”

B. Musk’s Prior Compensation Plans

Prior to the challenged transaction, Musk received two compensation plans from Tesla—one in 2009 and one in 2012. Both were equity linked. The first included a performance-based component. The second was entirely performance based.

1. The 2009 Grant

On December 4, 2009, the Board approved Musk’s first compensation plan (the “2009 Grant”). The 2009 Grant comprised two parts, each of which offered Musk stock options to purchase 4% of Tesla’s fully diluted shares as measured at the grant date.

The first part of the 2009 Grant vested automatically in tranches, with 1/4th vesting immediately and 1/48th vesting each month over the following three years, assuming that Musk continued to work at Tesla.

The second part of the 2009 Grant was performance based, offering Musk an additional 4% of Tesla’s fully diluted shares prior to the grant date for achieving each of the following: “successful completion of the Model S Engineering Prototype”; “successful completion of the Model S Vehicle Prototype”; “completion of the first Model S Production Vehicle”; and “completion of the 10,000th Model S Production Vehicle.” The 2009 Grant required that Musk meet these milestones within four years; otherwise, he forfeited his right to the unvested portions.

Tesla began delivering its next electric car model, the Model S, in June 2012 and Musk achieved all the 2009 Grant’s performance milestones by December 31, 2013.

2. The 2012 Grant

Before the 2009 Grant milestones had been achieved, on August 1, 2012, the Board approved a second compensation plan for Musk (the “2012 Grant”). The 2012 Grant involved ten tranches, each offering options representing 0.5% of Tesla’s outstanding common stock as of August 2012. For a tranche to vest, Tesla would have to achieve both a market capitalization milestone and an operational milestone. Each tranche required Musk to increase Tesla’s market capitalization by $4 billion—an increment greater than Tesla’s $3.2 billion market capitalization 18 trading days before the Board approved the 2012 Grant. The operational milestones required Tesla to accomplish specified product-related goals, such as developing and launching the Model X and the Model 3, and reaching aggregate production of 300,000 vehicles. The milestones worked in tandem. For example, one tranche would vest if Tesla achieved one of the operational milestones and a market capitalization increase of $4 billion, while two tranches would vest if Tesla achieved two of its operational milestones and a market capitalization increase of $8 billion. The 2012 Grant had a ten-year term.

By the end of 2016, Tesla had achieved seven of the market capitalization milestones and five of the operational milestones of the 2012 Grant, with another four operational milestones “considered probable of achievement.” By March 2017, seven of the 2012 Grant’s ten tranches had vested.

From the Board’s perspective, the 2012 Grant was successful. In only five years, Tesla’s market capitalization grew by over 15x from $3.2 billion to $53 billion. Tesla saw significant operational growth as well, designing and launching the Model S, Model X, and Model 3, and increasing its total annual vehicle production from approximately 3,000 total vehicles in 2012 to more than 250,000 vehicles in 2017. Musk worked hard toward these goals. And he was paid extremely well. In the end, the value of Musk’s holdings increased from approximately $981 million to $13 billion, meaning that Musk ultimately received approximately 52x the 2012 Grant’s grant date fair value.

C. The Compensation Process Takes Off.

In 2017, Tesla was already nearing completion of the 2012 Grant milestones, even though the 2012 Grant had a ten-year term. This prompted a discussion that led to the compensation plan at issue in this litigation (the “2018 Grant” or the “Grant”). By this time, Musk had accumulated beneficial ownership of 21.9% of the outstanding shares of Tesla common stock through his early investments and the two prior grants.

1. Meet The Decision Makers.

At all relevant times, Tesla had a nine-person Board comprising Musk, Kimbal, Brad W. Buss, Robyn M. Denholm, Ira Ehrenpreis, Antonio J. Gracias, Steve Jurvetson, James Murdoch, and Linda Johnson Rice. The Board had a standing compensation committee (the “Compensation Committee”), which was responsible for negotiating Musk’s compensation plan. Ehrenpreis, Buss, Denholm, and Gracias served on the Compensation Committee, with Ehrenpreis as chair. Musk and Kimbal recused themselves from most of the meetings and all of the votes on the 2018 Grant, and Jurvetson had prolonged leaves of absence during the relevant period. The fiduciaries responsible for Tesla in connection with the 2018 Grant, therefore, were the Compensation Committee members plus Murdoch and Johnson Rice.

a. The Compensation Committee Members

i. Ehrenpreis

Ehrenpreis is a founder and managing partner of DBL Partners, an impact-investing venture-capital firm that focuses on driving environmental change through investments. Ehrenpreis and DBL have invested tens of millions of dollars in Musk-controlled companies.

Ehrenpreis had been a member of the Board since 2007 and chair of both the Compensation Committee and the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee since 2009. Between 2011 and 2015, Ehrenpreis was granted 865,790 Tesla options. He exercised less than a quarter of those options in 2021, netting over $200 million. Being a Tesla director had “been a real benefit in fundraising” for Ehrenpreis’s funds.

Ehrenpreis and the Musk brothers have known each other for over 15 years. As Ehrenpreis acknowledged, his personal and professional relationship with the Musk brothers has had a “significant influence on his professional career[.]”

To argue that Ehrenpreis’s relationship with Musk was weighty in other ways, the plaintiff points to a July 2017 tweet in which Ehrenpreis professed his love for Musk. But the exchange does not reveal the deep relationship that the plaintiff described. It was an irrelevant joke.

Ehrenpreis is a close friend to Kimbal. They had known each other since at least 1999, and Ehrenpreis attended Kimbal’s wedding in Spain. Ehrenpreis also invested in Kimbal’s company, The Kitchen Group—a family of restaurants based in Colorado and Chicago.

ii. Buss

Buss joined the Board and the Compensation Committee in 2009. He worked as an accountant and in the semiconductor field until his retirement in 2014, and then served as CFO of SolarCity Corp. until February 2016. Buss had no personal relationship with Musk or other members of the Board and has never invested in any of Musk’s other businesses.

From 2014 through 2016, Buss’s held assets valued at between $30 and $60 million, not including his Tesla and SolarCity holdings. He earned about $2 million in total compensation from his work with SolarCity. Between 2011 and 2018, Buss reported that compensation as a Tesla director was approximately $17 million. He realized about $24 million for sales of Tesla shares that he received as compensation prior to January 21, 2018.

Buss owed roughly 44% of his net worth to Musk entities. Buss lacked any other personal or business connections to Tesla and left the Board soon after the Board approved the 2018 Grant.

iii. Denholm

Denholm joined the Board and the Compensation Committee in 2014. Her background is in accounting and telecommunications. She was recruited to the Board by Buss, who she knew professionally. Musk asked Denholm to be Board chair in 2018 following a settlement with the SEC (the “SEC Settlement”) that required Musk to relinquish his chairmanship.

Denholm does not appear to have had any personal relationship with Musk outside of her service on the Board. Denholm derived the vast majority of her wealth from her compensation as a Tesla director. Denholm’s compensation from Tesla between 2014 and 2017 was valued at about $17 million when it was issued, an amount she acknowledged was material to her at the time. Denholm ultimately received $280 million through sales in 2021 and 2022 of just some of the Tesla options he received as part of her director compensation. She described this transaction as “life-changing.” Denholm testified that between 2017 and 2019, she received approximately $3 million per year in her non-Tesla position. Even assuming Denholm valued her Tesla compensation at a fraction of its Black-Scholes value, her Tesla compensation far exceeded the compensation she received from other sources.

iv. Gracias

Gracias joined the Board in 2007 and the Compensation Committee in 2009. He founded and continues to manage Valor Equity Partners (“Valor”), a private-equity firm with approximately $16 billion under management. For years, Valor has also been “deeply operationally engaged in” Tesla. Valor actively assisted management in trying to drive sales for and lower the cost of production of Tesla’s Roadster model.

Gracias has amassed “dynastic or generational wealth” from investing in Musk’s companies. Gracias invested in PayPal in the 1990s, returning “roughly 3x to 4x.” Valor began investing in Tesla at Musk’s invitation in 2005. By 2007, Valor had invested $15 million. Valor ultimately distributed some of its Tesla shares to its investors, including Gracias. As of 2017, Gracias was the third-largest individual investor in Tesla, with virtually all of his Tesla shares held in trust for his children. As of 2021, that Tesla stock was worth approximately $1 billion. Valor and Gracias have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in SpaceX, SolarCity, The Boring Company, and Neuralink, all of which significantly increased in value.

All told, Gracias and his fund have netted billions of dollars by investing in Musk’s companies, many of which were made only with Musk’s personal invitation. Gracias has touted endorsements from Musk in marketing his own fund.

Musk and Kimbal have invested in Gracias’s ventures. At Gracias’s request, Musk invested $2 million in Valor no later than 2003 and an additional $2 million in 2007. Musk planned to invest in another Valor fund in 2013, but he ultimately did not because Gracias was concerned about conflicting fiduciary duties. Kimbal also invested $1 million to $2 million in Valor, and Valor invested a total of between $15 million and $20 million in two of Kimbal’s ventures. Gracias personally donated up to $500,000 to Kimbal’s charity and served on its board.

Gracias and Musk are “close friends.” Gracias once personally loaned $1 million to Musk and could not recall if he charged Musk interest. They meet outside of work as frequently as once a month. They have spent the night at each other’s homes. They have vacationed together with their respective families, including a trip to illusionist David Copperfield’s Bahamian island, a trip to Africa, and a ski trip. They have spent Christmas together. They have a long-standing tradition of spending Presidents’ Day weekend together with their families at Gracias’s home in Jackson Hole. Gracias attended Musk’s second wedding and was a groomsman at Kimbal’s wedding in 2018. Gracias has attended birthday parties for both Musk brothers and their children. Gracias is friends with two of Musk’s cousins and has taken numerous vacations with them. Gracias is also friendly with Musk’s mother and sister.

b. The Other Directors

i. Murdoch

Murdoch’s professional background is in media and entertainment. At the time he joined the Tesla Board, he was the CEO of 21st Century Fox. Murdoch met Musk in the late 1990s, but they lost touch until Murdoch purchased a Tesla Roadster in 2006 or 2007. The two became friends thereafter, meeting when they happened to be in the same city. Before he joined the Board, Murdoch, and Musk took family vacations together to Israel, Mexico, and the Bahamas. During one of these trips, which Gracias and Kimbal also attended, Musk asked Kimbal to help him decide whether to add Murdoch to the Board. After the trip, Gracias and Musk invited Murdoch to join the Board, and he agreed. Murdoch and Kimbal are also friendly, and Murdoch attended Kimbal’s wedding in 2018. As of December 31, 2017, Murdoch owned 10,485 Tesla shares through a family trust. He bought these shares on the market before anyone approached him to become a director. Murdoch now runs a private-investment company, which invested approximately $50 million in SpaceX in 2019 and 2020. Murdoch also personally invested approximately $20 million in SpaceX in 2019.

Murdoch received total compensation of approximately $35,000 in cash for his service as a Tesla director in 2017 and 2018.

ii. Johnson Rice

Johnson Rice joined the Board on Gracias’s recommendation. She and Gracias were friends and ran in the same social circle in Chicago. Johnson Rice’s sole employer before and during her time at Tesla was a family business, Johnson Publishing Company, which published the magazines Ebony and Jet. She has also served on a number of other boards. Johnson Rice declined to stand for re-election in 2019. Although she received Tesla options as compensation for her work as a director, they expired without being exercised.

2. Musk Proposes Terms Of A Compensation Plan.

The first mention in the record of what would become the 2018 Grant is a text from Ehrenpreis to Musk sent on April 8, 2017—one day after Tesla’s Compensation Committee certified vesting of the 2012 Grant’s sixth tranche. Ehrenpreis asked Musk to discuss “a few comp related issues.” They spoke by phone on April 9. Ehrenpreis testified that he had reached out to Musk to see if he was “ready to recommit” and “to figure out . . . was his head in a place that he wanted to recommit over a longer duration to Tesla[?]”

Musk put forward terms of a new compensation plan during the April 9 call. He envisioned a purely performance-based compensation plan, structured like the 2012 Grant but with more challenging market capitalization milestones and proposed 15 milestones of $50 billion in market capitalization—a total possible award of 15% of Tesla’s outstanding shares.

To put Musk’s proposal in perspective, each market capitalization milestone increase of $50 billion required Tesla to grow in size roughly equal to the market capitalizations of each of Tesla, Ford, and GM as of early 2018. So, Tesla would have to grow an amount in market capitalization equal to that of the most significant domestic car manufacturers for Musk to earn a single tranche of compensation. Musk viewed this proposal as “really crazy.”

Musk’s initial proposal is reflected in a draft of the proxy statement issued in connection with the 2018 Grant. The draft states:

On April 9, 2017, . . . Ira Ehrenpreis, the Chairman of the Compensation Committee, and Mr. Musk discussed the possibility of a new performance award that would have an incentive structure similar to the 2012 Performance Award but with even more challenging performance hurdles.

Mr. Musk expressed interest in such an arrangement and suggested a compensation structure that would incentivize management to grow Tesla into one of the most valuable companies in the world.

During this meeting, Mr. Musk suggesting performance milestones that would trigger stock option awards of 1 % of the Company’s current total outstanding shares based on incremental $50 billion increases in market capitalization, such that if Tesla grew by $750 billion, a maximum possible award would amount to 15% of the Company’s current total outstanding shares.

Mr. Musk indicated that such an award structure would align his incentives with those of stockholders and incentivize him to continue leading the management of the Company over the long-term.

Mr. Ehrenpreis indicated that the Compensation Committee would consider Mr. Musk’s perspectives as part of its analysis.

Language like the above appears in other drafts but not in the final proxy statement.

The draft proxy statement is the most reliable (indeed, the only) evidence of the substance of the April 9 discussion. Neither Musk nor Ehrenpreis took contemporaneous notes or otherwise memorialized their April 9 discussion. By the time of discovery and then trial in this action, Musk had only vague memories of the discussion, and Ehrenpreis had no memory of it at all.

It is unclear who prepared the draft proxy statement, but Maron, Tesla’s General Counsel, was responsible for it. Maron testified he spoke to Ehrenpreis within hours of the April 9 call and reviewed the draft.

Maron was totally beholden to Musk, lending credibility to the accuracy of the draft proxy statement. But his relationship with Musk raises concerns as to other aspects of the process during which Maron advised the Board and Compensation Committee. Maron joined Tesla as Deputy General Counsel in September 2013, and was promoted to General Counsel in September 2014, reporting directly to Musk. Before joining Tesla, Maron was Musk’s divorce attorney. Maron neither socialized with Musk nor considered himself a friend of Musk when he worked at Tesla, but he owed his career to and had genuine affection for Musk. Both in his deposition and at trial, Maron held back tears when asked about his departure from Tesla in January 2019, describing it as “the most difficult decision[]” he had made to date.

After speaking to Ehrenpreis on April 9, Maron enlisted other Tesla employees to help him model Musk’s proposal. All told, 13 in-house Tesla executives worked on the 2018 Grant. The key executive in addition to Maron was Ahuja, Tesla’s CFO.

At the outset of his involvement, Ahuja recommended one substantive change to the structure—pairing the market capitalization milestones with operational milestones. He recommended this change for accounting purposes. Maron relayed the change to Ehrenpreis, who questioned whether operational milestones were necessary. Maron explained that “there’s an important account[ing] reason” for having operational milestones.

Maron’s team began analyzing Musk’s initial proposal on April 10, roping in Tesla’s legal counsel at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati (“Wilson Sonsini”)and lining up compensation consultants. Maron proposed retaining Compensia, Inc., a compensation consulting firm that Tesla had engaged in connection with the 2009 and 2012 Grants, but he also provided four other options for Ehrenpreis to consider.

3. Musk States That He Is Committed To Tesla For Life.

Little progress was made on Musk’s new compensation plan through May 2017. During a May 3 earnings call, an analyst asked about Musk’s “view of staying actively in place with Tesla longer into the future[.]” Musk responded that he should not be “CEO forever.” He further indicated that he was going to reevaluate his position after Tesla achieved volume production of the Model 3.

The plaintiff argues that Musk’s statement about not being “CEO forever” was intended to pressure Tesla in negotiations over Musk’s compensation plan, but the record does not support that conclusion. Musk clarified his statement later in the May 3 earnings call, saying:

Well, maybe I wasn’t clear. I intend to be actively involved with Tesla for the rest of my life. Hopefully, stopping before I get too old—or too crazy, I don’t know. But essentially for as long as I can positively contribute to Tesla, I intend to be—to have a significant involvement with Tesla.

In other words, Musk had every intention of remaining “significant[ly] involved” in some leadership role at Tesla, even though he did not envision himself being “CEO forever.” Musk repeated this assertion at trial, stating unequivocally that he would have remained at Tesla even if stockholders had rejected a new compensation plan because he was “heavily invested in Tesla, both financially and emotionally, and viewed Tesla as part of his family. ”Trial witnesses similarly testified that they never heard Musk say he had any plans to quit Tesla. And even though Musk did not intend to stay CEO forever, he had no immediate plans to resign from that position. Corroborating that fact is lack of any succession plans during the relevant period. That is, before 2021, neither Musk nor Tesla had identified a potential successor for the role of Tesla CEO.

4. The First (And Forgettable) Board Discussion

By June 5, 2017, Tesla had met all ten CEO market capitalization milestones for the 2012 Grant and had only three tranches of operational milestones left to achieve. The Board first discussed the prospect of a new compensation plan for Musk during a June 6, 2017 Board meeting. Musk chaired the meeting.

The Board’s conversation during the June 6 meeting concerning Musk’s compensation was brief and, apparently, forgettable. During that meeting, Ehrenpreis updated the Board on the near fulfillment of the 2012 Grant milestones and stated that “plans were underway to design the next compensation program” for Musk. The minutes of that meeting are three pages long, and the discussion of a new compensation plan was limited to a sentence. At least one director who served on the Compensation Committee, Denholm, did not recall the June 6 Board discussion at all. She testified at trial that any discussion of a new compensation plan during the June 6 Board meeting must not have been substantive.

5. Musk Accelerates The Process.

On June 18, 2017, Maron emailed the Compensation Committee stating: “We would like to . . . discuss Elon’s next stock grant.” This sort of outreach from Maron was common during the process. Although he was counsel to Tesla, he would reach out and prompt action by the Compensation Committee to benefit Musk (the “we” in the prior quote).

A few days prior, on June 15, 2017, Maron’s team had prepared an aggressive timeline for approving a compensation plan. The timeline scheduled the Compensation Committee and Board to approve the plan by July 17 or by July 24 at the latest. The initial June 15 plan contemplated only two Compensation Committee meetings prior to final approval and allotted the committee just over a month to do its job. A later June 26 version of the timeline was even more rushed, proposing only one Compensation Committee meeting (with an additional meeting if necessary) and giving the committee less than three weeks to complete its task. That timeline envisioned that on July 7, the Compensation Committee would “[g]ain agreement on proposed approach, award size and metrics/goals” and “[g]ain preliminary approval of grant agreement[.]”

The timeline reflected a reckless approach to a fiduciary process, given that the Compensation Committee had not yet discussed any substantive terms nor met concerning the Grant. Despite the break-neck speed contemplated by the timeline, Maron reported to counsel on June 18 that Ehrenpreis was “aligned on the plan and timing.”

After Musk asked to discuss his compensation plan, the Maron-led team was supercharged. They conducted initial calls with five potential compensation consultants and selected three for Maron and Ehrenpreis to interview. During the initial calls, the consultants were informed of Musk’s initial proposal and the aggressive timeline leading to a late-July approval. Maron and Ehrenpreis updated Musk about the process on June 20, 2017.

6. The First Compensation Committee Discussion

The Compensation Committee discussed Musk’s compensation plan for the first time on June 23, 2017. The committee formally resolved to retain Wilson Sonsini and Compensia as legal advisor and compensation consultant, respectively. A few days later, Tesla retained Jon Burg at Aon Hewitt Radford (“Radford”) to value the 2018 Grant in light of the market-based milestones and to advise on the accounting treatment of the 2018 Grant in light of the performance-based milestones. During the meeting, Ehrenpreis stated that the Compensation Committee’s aim was to create a new compensation plan similar to the 2012 Grant. The committee then set out the goals for the compensation plan in broad strokes. The minutes of the meeting describe that discussion as follows:

The Committee discussed how Mr. Musk had been and would likely remain a key drive of the Company success and its prospects for growth, and that, accordingly, it would be in Tesla’s interest, and in the interest of its stockholders, to structure a compensation package that would keep Mr. Musk as the Company’s fully engaged CEO. The Committee also discussed the fact that unlike most other Chief Executive Officers Mr. Musk manages multiple successful large companies. The Committee discussed the importance of keeping Mr. Musk focused and deeply involved in the Company’s business, and the corresponding need to formulate a compensation package that would best ensure that Mr. Musk focuses his innovation, strategy and leadership on the Company and its mission.

The minutes do not reflect any discussion by the committee concerning the effect of Musk’s pre-existing 21.9% equity stake on these goals.

The committee was not presented with any proposed terms for a compensation plan, and it did not consider any. This was the case even though, behind the scenes, Ehrenpreis and Musk had discussed Musk’s initial proposal, which Musk’s team had already modeled.

Although the committee had no idea what the terms of the plan might be, they were told to be prepared to approve it in July. Brown thought the timeline was unwise. Brown called Ehrenpreis to ask for more time to work on the matter, but Ehrenpreis responded that “this is the timeline we are working with.” A member of Maron’s team would later repeat that message, telling both Brown and Burg that “we are running up against a short deadline and we have to make sure this keep [sic] moving.” The message was clear—move at full tilt. Other than Brown, there is no evidence that anyone questioned the timeline.

7. The First Working Group Meeting

After the June 23 Compensation Committee meeting, Ehrenpreis formed a “Working Group.” The group consisted of Maron and at least two in-house attorneys who reported to him (Phillip Chang and Phuong Phillips), Ahuja, Brown, Burg, and attorneys from Wilson Sonsini. Ehrenpreis and Gracias were in the Working Group, but the Compensation Committee decided that the two members with less extensive ties to Musk—Denholm and Buss—were “optional” attendees.

The Working Group first met on June 30. Phillips proposed the agenda, and Brown prepared a slide deck with a high-level overview of the suggested terms of Musk’s new equity plan. In relevant part, the presentation included: a few slides summarizing the 2012 Grant; a slide titled “Preliminary Concept,” reflecting the 15-tranche combined market and operational goals structure; and three slides titled “Key Program Terms: Alternatives and Considerations,” which identified terms of the compensation plan under the title “Preliminary Alternatives” and considerations relevant to each term under the title “Considerations/Decision Points.”

The presentation identified the following question for discussion: “Will both operational and company valuation goals be used?” By framing the structure as a question, the presentation suggests that it was an open issue. Brown’s notes on a June 26 draft version of this presentation, however, reflect that the issue had in fact been resolved. He wrote that: “there will be 15 goals of each type[,]” referring to both market capitalization and operational goals, and “the market cap goals are increments of $50B, for a total of $750B of incremental market cap growth for all 15 tranches (yes, there [sic] numbers are what they are thinking!)[.]” In part, therefore, the presentation was a vehicle for getting the Compensation Committee members up to speed on the work done behind the scenes prior to that time.

After the June 30 meeting, the Working Group stood poised to move forward. Chang emailed members of the group about developing operational milestones, including a structure in which each market capitalization milestone would also require an increase of $15 billion in GAAP revenue. Chang stated that Tesla should “expect to achieve a milestone roughly once every 12 to 15 months over the next 3 years.”

8. Musk Decelerates The Process.

The Working Group met again on July 6, the day before the next Compensation Committee meeting. After this meeting, Maron informed Chang, Ahuja, and others that “we’re now going on a slower track with the CEO grant. We’re now looking to issue it in August or September instead of within the next couple of weeks.”

Maron professed ignorance as to why the timeline decelerated. Chang and Phillips too lacked any recollection. Ehrenpreis testified that “it was way too complex to do under what was originally described as a preliminary timeline” but did not recall additional details. Brown testified that he received pushback when he asked to extend the timeline, so he was not the impetus for the delay. Maron would not have made the determination to extend the timeline to August or September unilaterally. The reality is that Maron answered to and spoke for Musk in this context. It was Musk who either asked to slow things down or stopped pushing to get them done so quickly.

Phillips circulated “the proposed new timeline for Elon’s equity grant” to the Working Group on the evening of July 6. The initial timeline contemplated preliminary approval by the Compensation Committee on July 7 and final approval by the committee and Board approval by July 24. The revised timeline pushed final approval by the committee and Board out to September 8 and September 19, respectively.

9. The First Compensation Committee Discussion Of The Substantive Terms

The July 7 Compensation Committee went forward as scheduled, but the agenda was revised given the new timeline. The revised agenda included “a short presentation re the CEO grant” from Brown. This was the first meeting where the committee would be presented with terms of a compensation plan.

In addition to the $50 billion market capitalization milestones that Musk had proposed, Brown’s presentation covered alternatives—a flat $25 billion increase or graduated milestones beginning at $10 billion and increasing to $50 billion. These different market capitalization approaches corresponded to different award sizes, ranging from 7.5% of total outstanding shares to Musk’s proposed 15%.

Although the presentation identified alternatives to Musk’s proposal, the presentation included a valuation only for Musk’s proposal. The presentation was therefore biased toward Musk’s proposal, although this was the first meeting at which the committee had considered any terms.

In addition to the market capitalization and operational milestones, the presentation identified other potential grant features, including the following:

- A “Clawback Provision.” Around April 2015, the Board adopted new Corporate Governance Guidelines (the “Guidelines”) providing that Tesla’s “executive officers [are] subject to a clawback policy relating to the repayment of certain incentives if there is a restatement of our financial statements.’” The presentation contained the following question: “Is the current clawback provision sufficient protection for the Company?” There is no evidence that the committee discussed this question or ever demanded a more protective Clawback Provision. The final version of the Grant included a Clawback Provision based on the Guidelines.

- An “M&A Adjustment,” which is a provision that accounts for the impact of financing or acquisitions on the market capitalization milestones (“M&A Adjustment”). These provisions are standard.

- A “Hold Period,” which was a period post-exercise during which Musk would be prohibited from selling his stock. The presentation noted that “post-exercise hold periods decrease the grant/accounting value” of the stock as follows: “2 year = -15%; 3 years = -18%; and 5 years = -22%.”

Benchmarking analyses were on the advisors’ minds. Prior to the first Working Group meeting, Phuong suggested an agenda item addressing “[b]enchmark companies – risks associated with such grant.” And Brown’s presentation for the July 7 Compensation Committee meeting contained an appendix listing the “Largest CEO Pay Packages in 2016”; summaries of other executive compensation plans at SolarCity, Nike, Avago Technologies, and Apple; Radford’s $3.1 billion valuation of a grant featuring $50 billion market capitalization milestones and awarding 15% of total outstanding shares; and Radford’s additional preliminary models based on different market capitalization approaches. But the appendix data does not constitute a traditional benchmarking study, and it is unclear whether the committee discussed this information or the “risks associated with such grant” in any event.

10. Stockholder Outreach

During the July 7 meeting, the Compensation Committee tasked Ehrenpreis and Maron with contacting Tesla’s largest institutional stockholders to discuss Musk’s new compensation plan. Maron’s team worked with outside counsel to prepare talking points to use during the calls. They ultimately spoke to 15 stockholders between July 7, 2017, and August 1, 2017. Maron’s subordinates joined these calls and took notes.

As scripted, Ehrenpreis was to: introduce himself and Maron and identify his objectives as Compensation Committee chair (to “keep executives engaged and performing their best”); sing Musk’s praises (“I think we can all agree that he’s an extraordinary leader and continues to accomplish incredible things for Tesla and its stockholders”); remind the stockholders of the “[i]ncredible success of the 2012 Grant”; and explain that they are considering a new compensation structure for Musk and that “[o]bviously, the goals of the new program will be similar to the 2012 grant[.]”

In this litigation, the defendants report that the stockholders to whom Ehrenpreis and Maron spoke “were pleased with the 2012 Plan’s results and supported a similar approach for a new compensation plan,”and that stockholders also provided suggestions for the new compensation plan that the Board ultimately adopted. It is difficult to credit the defendants’ narrative for two reasons. First, the script reads like a loaded questionnaire intended to solicit positive stockholder feedback and not a method for gaining objective stockholder perspectives on a potential new plan. There is nothing inherently wrong with the script; it simply undermines the evidentiary weight of the resulting communications. Second, what the stockholders said in response to these inquiries is hearsay and untested by the adversarial process, including cross examination.

11. The Working Group Develops Operational Milestones.

The Working Group next met on July 17.One of the objectives for the meeting was to establish a metric for operational milestones. Brown prepared a presentation for the meeting that listed the following potential operational metrics: “EBITDA; operating income; free cash flow; gross margin; strategic/execution goals” (such as introducing a new model or producing a certain number of units, as in the 2012 Grant); and “Return Metrics (ROA, ROIC, ROE),” with each option paired with a handful of “advantages” and “disadvantages.”

Ahuja had developed the strategic milestones for the 2012 Grant, and he took responsibility for developing the operational milestones for the 2018 Grant. On July 19, Burg sent Ahuja and other members of the Working Group an analysis of the historical market capitalization-to-revenue ratio of large U.S. companies. Ahuja used this data to propose starting with a 6.5x revenue-to-market-capitalization-milestone ratio, which could be used to determine the initial revenue milestones— $7.5 billion additional revenue for each $50 billion in market capitalization. The revenue milestones then declined to 4x for the final tranches at increments of $12.5 billion for each $50 billion market capitalization increment.

On July 23, Ahuja suggested four EBITDA milestones in addition to the 15 revenue-based milestones: $4 billion, $8 billion, $12 billion, and $16 billion. Ahuja projected that Tesla “should be able to get to $12B EBITDA in the next 4–5 years depending on volumes . . . and margin assumptions[.]”

The agenda for the July 17 Working Group Meeting included discussion of an M&A Adjustment and a Hold Period. Brown prepared a detailed slide on the M&A Adjustment, but there are no contemporaneous communications reflecting discussion of the adjustment beyond that slide.

As to the Hold Period, the presentation noted that the Guidelines required a six-month post-vesting Hold Period. The next day, Phillips emailed Burg and Brown a question from Ehrenpreis about “creative options” they could employ to “solve for getting a bigger discount” on the publicly reported grant date fair value, such as extending the Hold Period to five years (the “Five-Year Hold Period”). Burg provided holding periods ranging from one to ten years and types of options with corresponding discounts.

After the July 17 meeting, the Working Group began planning for an August 1, 2017 Compensation Committee meeting. The agenda for the meeting included an update for the full Board (excluding Musk and Kimbal) on the structure under discussion for the compensation plan and on stockholder feedback on the structure. Maron sent an email to the full Board on July 27, summarizing the process to date and asking everyone to attend upcoming Compensation Committee meetings.

12. Musk Hits The Brakes.

Late July 2017 proved a busy time for Tesla, which delivered the first Model 3 on July 29. This triggered the eighth milestone in Musk’s 2012 Grant. It also prompted Musk to, once again, reset the Compensation Committee’s timeline. In Maron’s view, given the struggles with the Model 3 launch, Musk’s desired to extend the timeline either because he was unsure whether to commit to Tesla (which Musk denied) or simply did not want to focus on compensation during a busy time.

Whatever the reason, Musk hit the brakes on the process. On June 30, two days before the planned Compensation Committee meeting, Musk sent Maron a brief email asking to put the discussion of his compensation “on hold for a few weeks[.]” Maron replied that he would “rather keep cranking on it . . . because there’s a fair amount to it that we’ve been working on with the board and there’s lead time involved.” Musk agreed to let Maron proceed, stating that he “[j]ust want[ed] to make sure Tesla interests come first.” Musk reminded Maron that “[t]he added comp is just so that I can put as much as possible towards minimizing existential risk by putting the money towards Mars if I am successful in leading Tesla to be one of the world’s most valuable companies. This is kinda crazy, but it is true.”

D. The Process Goes Off Course.

By August 2017, Musk remained hyper-focused on Model 3 production, which was proving slow and painful. As Musk described at trial, “[t]he sheer amount of pain required to achieve that goal, there are no words to express.” This aspect of Musk’s testimony was totally credible.

Although Musk agreed to allow Maron to “keep cranking,” progress on Musk’s compensation plan had slowed to a halt. From August through September, there was some discussion of Musk’s compensation plan but no action, and there were no meaningful discussions of the 2018 Grant in October. The highlights of this interregnum are discussed in brief below.

The Compensation Committee held a telephonic meeting on August 1, and Compensia made a presentation during that meeting that summarized the committee’s progress to date. The most notable aspect of this meeting concerned the following “key question” that went undiscussed: “Is additional compensation for the CEO required given his current ownership and its potential appreciation with Company performance?” Musk had made his initial proposal in April 2017, and the original timeline had the process wrapping up by July 2017, but this was the first time that this “key question” had been posed—did Musk require additional compensation? The most curious thing about this question is that there is no evidence that any director deliberated over it, and it did not appear in any other Board or committee materials.

The next event of interest occurred on September 8, when Ehrenpreis and Denholm spoke to Musk to discuss his compensation plan. Once again, the most notable aspect of this conversation concerns a question that went undiscussed. The agenda for the September 8 call identified the following topic for discussion: “Should some type of commitment be included as part of comp structure?” Trial testimony revealed that no one raised this issue with Musk. Ehrenpreis recalled discussing Musk’s dedication to Tesla generally. And Maron’s summary of the call reflects that the participants discussed the “opportunity costs” of Musk devoting time to Tesla. Although Musk didn’t “have a good recollection of [the September 8] call,” he was confident that they did not discuss a time or attention commitment “vis-à-vis [Musk’s] other interests.” Musk said “that would be silly.”

The Board met on September 19, but the meeting was not terribly interesting. Ehrenpreis reported on the committee’s progress and the September 8 conversation with Musk. Brown gave a presentation covering much of the same ground as the August 1 presentation. Brown valued the 15% market capitalization option at a $2–3 billion grant date fair value. According to the meeting minutes, “[t]he Board expressed its general support for the overall structure of” the Grant, meaning the 15-tranche structure.The Board favored “a long-term stock option grant . . . with performance-based vesting, primarily keyed to the market capitalization of the Company[.]” The Board noted that “Musk was driven by large goals[,]” and “viewed the discussed targets as achievable given the potential of the Company and believed that Mr. Musk would as well.”

Before this period of inactivity, the only milestones that had been discussed were the $50 billion market capitalization milestones. Operational milestones remained “TBD,” but Ahuja gave some thought to them in August and September. There was a Working Group meeting on August 3, and after that time, discussions focused on adjusted EBITDA. It is unclear who made the decision to focus on that metric.

On August 17, Ahuja asked one of his employees for “operational metrics [that] will line up with 15 increments of $50B in market cap.” Ahuja envisioned 15 adjusted EBITDA milestones “ranging from $2B to $25B” and requested comparisons to historic EBITDA/market capitalization correlations for Apple, Amazon, and Google. After pulling the data, members of Ahuja’s team responded that they “didn’t see immediate parallels to where we are.” Ahuja requested more information on the data they gathered concerning “% Adjusted EBITDA/Revenue and Market Cap to Adjusted EBITDA multiple.”

The day after the September 19 Board meeting, Ahuja reached out to his team for help developing “10 Adjusted EBITDA based metrics that end at a revenue of about $150B and market cap of about $800B using % and multiples which start high and progressively become lower.” He explained that “[t]he thinking is that we will develop EBITDA based operational metrics rather than [r]evenue based.” It is unclear who dictated that “thinking” at the time. A Tesla employee responded to Ahuja’s request on September 21, providing ten potential EBITDA milestones (going from $2 billion to $20 billion in even increments of $2 billion, similar to Ahuja’s range). The data reflected adjusted EBITDA/revenue ratios of Tesla and its peers (e.g., Apple (34%) and Google (42%)). The employee found that Ahuja’s proposed EBITDA milestones range would necessitate an EBITDA-to-market-capitalization multiple well above that of Amazon, Apple, or Google.

E. The Process Restarts.

By the end of October, Tesla’s production difficulties seemed to be easing. A “Quarterly Update Letter” signed by Musk and Ahuja for the Board’s audit committee (the “Audit Committee”) at its October 31, 2017 meeting was generally optimistic. It stated that the “production rate will soon enter the steep portion of the manufacturing S-curve,” which would create “non-linear production growth” in the following weeks. With Tesla’s production stabilizing, Musk turned his attention back to his compensation plan.

1. Musk Lowers His Ask.

In the early hours of November 9, Musk sent Maron an email stating that he wanted to “move forward with [his compensation plan] now, but in a reduced manner from before.” Musk testified that by “reduced,” he meant something less than 15% of total outstanding shares. It is unclear why Musk decided to lower his ask. It is possible that he was just trying to single-handedly calibrate the compensation package to terms that were more reasonable. Later that morning, Musk told Maron that he would “like to take board action as soon as possible if they feel comfortable and then it would go to shareholders.”Musk stated:

I think the amount should be reduced to a 10% increment in my Tesla ownership if I can get us to a $550B valuation, but that should be a fully diluted 10%, factoring in that it dilutes me too. So if it hypothetical [sic] was awarded to me now and I own (probably) ~20% fully diluted, then I would have ~30%. Of course there will be future dilution due to employee grants and equity raises, so probably this is more like 25% or so in 10 years when it has some chance of being fully awarded.

The implication of Musk’s proposal to use a 10% fully diluted figure at 1% per tranche is that he now sought a ten-tranche structure.

Moments later, Musk sent Maron another email stating:

Given that this will all go to causes that at least aspirationally maximize the probability of a good future for humanity, plus all Tesla shareholders will be super happy, I think this will be received well. It should come across as an ultra bullish view of the future, given that this comp package is worth nothing if ‘all’ I do is almost double Tesla’s market cap.

Ehrenpreis relayed Musk’s revised proposal to the Board at a special meeting on November 16, 2017. In advance of that meeting, Chang sent Ehrenpreis a list of talking points, stating the “[n]umbers we are talking about are now lower than before . . . 10 tranches to $550 billion; 1% per tranche[.]”

2. Some Turbulence

Meanwhile, on November 13, Jurvetson began a leave of absence. At the time, Jurvetson had been a managing director of Draper Fisher Jurvetson (“DFJ”), a venture capital firm with investments in Tesla and other Musk-related businesses. Following a scandal, Jurvetson was removed from DFJ. This became a “PR problem” for Tesla. Jurvetson returned to the Board in April 2019 but left again in September 2020. On November 14, Musk emailed Maron again, asking to “pause for a week or two” on his compensation plan as it would be “terrible timing.” At trial, Musk did not recall the nature of the problem. He is a smart person, though, and it is possible that he thought it was better to avoid releasing controversial news on the heels of controversial news.

3. Musk Further “Negotiates Against Himself.”

Musk’s November 9 proposal had the unintended consequence of raising Musk’s demand. According to Chang, Musk’s demand to increase his current percentage of fully diluted shares (approximately 18.9%) by ten percentage points (to approximately 28.9%) would require an award of 28,959,496 shares, which equaled approximately 17.23% of total outstanding shares as of November Musk’s November 9 request, therefore, turned out to be larger than his initial proposal, contrary to Musk’s desire for a “reduced” amount.

Maron sent Chang’s calculations to Musk on November 29. Maron presented to Musk both (i) the total amount of shares Musk would receive based on his November 9 request for an additional 10% on a fully diluted basis (28,959,456 shares); and (ii) the total amount of shares Musk would receive based on his March 2017 request for an award of 15% of total outstanding, non-diluted shares (25,217,325 shares).

Musk responded on December 1 telling Maron: “That is more than intended. Let’s go with 10% of the current FDS number, so 20.915M.” Musk arrived at this number by multiplying Tesla’s FDS (fully diluted share) total as of November 2017 by 10%, or by factoring in dilution on a pre-grant basis.

When asked about his December 1 proposal, Musk volunteered an answer that the plaintiff’s counsel has gleefully emphasized at every opportunity. He said that the December 1 proposal “was, I guess, me negotiating against myself.”

4. A Surge Of Activity

The parties crammed a lot of work into a few days in December. During a five-day period that month, the Compensation Committee met twice (on December 8 and 10), and the Board met once (December 12). There was a renewed sense of urgency after the December 8 meeting, as reflected by email chatter on December 10 and 11 among high-ranking Tesla employees enlisted to work on the Grant.

During the December 10 meeting, the Compensation Committee approved a 12-tranche Grant structure and a set of operational milestones. Ehrenpreis reported that Musk “appeared prepared to accept” the structure, which the minutes described at the “lower end of the previously contemplated range of 12% of the total outstanding shares.” The December 12 meeting minutes also identify other terms under consideration.

a. The 12%/12-Tranche Structure

All pre-November 9 discussions had assumed 15 tranches, in line with Musk’s proposals. And on November 9, Musk proposed ten tranches measured by fully diluted shares. On December 10, however, the Compensation Committee approved a 12-tranche structure, which was presented to the Board two days later. The parties dispute the evolution of the 12-tranche structure.

According to Ehrenpreis, the 12-tranche structure was intended to counter Musk’s offer for a fully diluted 10% and its corollary ten-tranche structure. This may appear counterintuitive, because 12% of total outstanding shares equals approximately 10% fully diluted—thus, making it seem like there was no real upside to using the 12% figure. The difference, however, is that adding two more tranches on top of Musk’s suggested ten tranches required Tesla to hit the $50 billion market capitalization target two more times to generate an additional $100 billion in market capitalization. So, the 12-tranche structure made it harder for Musk to achieve the maximum payout of the Grant. Musk testified that the shift from fully diluted to total outstanding shares was one of “two areas . . . where the board pushed significantly, which I conceded[.]”

This testimony, however, finds no support in the contemporaneous record. Although there are benefits of a 12-tranche structure to minority stockholders, the move to 12% and 12 tranches was driven by the Board’s preference to base the Grant on total outstanding shares rather than fully diluted shares.

The issue first arose during the November 16 Board meeting. There, the Board discussed a move from Musk’s proposed fully diluted shares to the Board’s preferred total outstanding shares. The Board viewed total outstanding shares as a simpler metric and had used it when issuing the 2012 Grant.

On December 10, the Compensation Committee held a special meeting to discuss the Grant. There are no minutes for the December 10 meeting. Chang attended and took notes, which he circulated by email later that evening. His notes state:

Todd Introduction/led discussion re review of terms

o We seem to be at the right place as far as size: 10% of

FDS (~12% of TOS)

o #of tranches?

Simplicity of 10

10 means that the end goal is smaller

Agreed to 12 tranches of 1% each.

Translating the above, the Board agreed to the size demanded by Musk but preferred to base it on total outstanding shares, consistent with their discussion during the November 16 meeting. With his meeting notes, Chang indicated that he would “send another email shortly with the grant size numbers.” A few minutes later, he sent an email to the same people attaching a spreadsheet and stating the following:

Contemplated size of grant is here. Details attached.

This is based on 12% of total outstanding shares (TOS as of 11/8, should update to close to grant, but this should still get us very close).

Grant size would be 20,173,860 shares.

• 12% of TOS

• 9.8% of FDS

On December 11, Ahuja emailed Chang and Tesla’s corporate controller to confirm that the 2018 Grant would award 20,173,860 shares (12% of total outstanding or 9.8% of fully diluted) over 12 tranches.

On December 12, Ehrenpreis told the Board that Musk was prepared to accept this Grant size.

There is no discussion in any of the minutes or notes of the November 16, or December 8, 10, or 12 meetings indicating that the Board desired 12 tranches because it was better for the minority stockholders. To the contrary, the only explanation in the record for the 12-tranche structure is that the Board preferred to measure the Grant by total outstanding shares for simplicity’s sake.

There is also no evidence that the Board pushed for the 12%/12-tranche structure. Maron did not recall the Board pushing or Musk conceding anything. He testified that although “the size of the overall plan” was one of the features that was “different than I think were initially thought of by Elon . . . I don’t want to say that it was necessarily over his objection.” Reinforcing the similarity between Musk’s 10% fully diluted ask and the Board’s 12% total outstanding offer, Musk confused the two at trial, mistakenly testifying that the Grant awarded “10 percent.”

b. The Operational Milestones

During the November 16 Board meeting, the Board “discussed the structure of the operational milestones,” came to a consensus to use both sales and profits metrics, and “directed the Compensation Committee and management to develop operational milestones” using revenue and EBITDA.

Ahuja and his team took up the mantle. On December 7 and 8, Ahuja developed a number of alternatives using a comparatively low 10% EBITDA/revenue margin. By December 10, Ahuja had refined the model to three options for six, eight, or 12 of each of revenue and adjusted EBITDA milestones, all at a 10% EBITDA/revenue margin.

Recall that, in September 2017, Tesla sought to develop achievable operational milestones and analyzed information regarding the adjusted EBITDA/revenue ratios certain peers (e.g., Amazon (8%), Apple (34%), and Google (42%)). The 10% EBITDA/revenue ratio modeled by Ahuja, therefore, was comparatively low and thus easier to achieve. Tesla ultimately based the Grant’s EBITDA milestones on an 8% EBITDA/revenue margin, making them even easier to achieve.

Ahuja explained his methodology at trial. He “started with” the $50 billion market capitalization milestones and backed into the revenue and EBITDA targets. Chang similarly explained that the operational and market capitalization milestones “have to be somewhat aligned. It has to make sense to be able to be achieved around the same time or what you think is the same time.” So to establish the operational milestones, the Working Group asked: “at this valuation what would . . . revenue and EBITDA look like . . . ?”

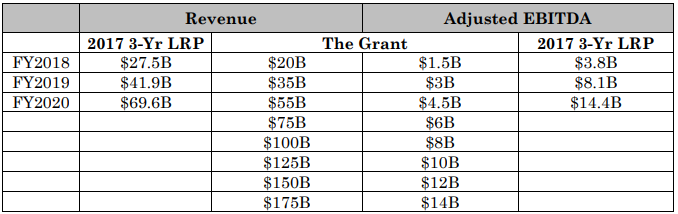

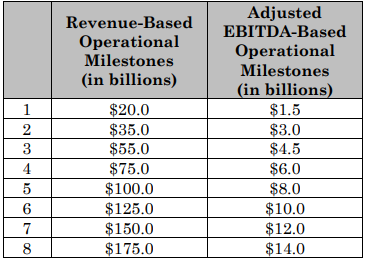

During the December 12 meeting, the Board also reviewed Tesla’s then-current operating plan and projections. Ahuja developed, and Musk approved, the projections in December prior to the meeting (the “December 2017 Projections”). The one-year projections underlying the operating plan forecasted $27.4B in total revenue and $4.3B in adjusted EBITDA by late 2018, and thus predicted achievement of three milestones in 2018 alone. The three-year long-run projections (“LRP”) underlying that plan reflected that, by 2019 and 2020, Tesla would achieve seven and eleven operational milestones, respectively. The following chart reflects the corollaries:

F. The Last Leg

The day after the December 12 Board meeting, Chang provided Burg and Brown the “near final” term sheet (the “December 13 Term Sheet”), stating that Musk was “well aligned” on the terms and that he expected Board approval in early January 2018. The key terms concerning structure and milestones had been finalized, which allowed Burg to complete the grant date fair value. Other terms, such as a Leadership Requirement (defined below), the Hold Period, and the M&A Adjustment would fall into place in the weeks ahead.

1. The Leadership Requirement

The December 13 Term Sheet reflected agreement on a “Leadership Requirement,” conditioning vesting under the Grant on Musk being “CEO or Executive Chairman and Chief Product Officer[.]”

The 2012 Grant contained a stricter Leadership Requirement, which conditioned vesting on Musk remaining CEO. The Board materials for the September 19 meeting reflect that the Board considered a Leadership Requirement similar to that in the 2012 Grant. At some point between September 19 and December 13, the Board relaxed its request to allow vesting if Musk was not CEO but was Executive Chairman and Chief Product Officer. There is no indication how or when the decision was made, whether it was raised with Musk, or when the term was finalized, but it appears in the final Grant.

At trial, Gracias explained that the more lenient Leadership Requirement reflected the Board’s belief that Musk’s “most valuable function[]” was as the “chief product officer,” not as the CEO. There is no evidence that the Board ever discussed or negotiated this with Musk.

2. The M&A Adjustment

The December 13 Term Sheet reflected the Board’s intent to include an M&A Adjustment in the Grant. The 2018 Grant included an M&A Adjustment, which had been under discussion since at least the June 23 Compensation Committee meeting. In its final form, the M&A Adjustment excluded from the market capitalization milestone acquisitions with a purchase price over $1 billion, and the revenue and adjusted EBITDA milestones excluded amounts attributable to acquisitions providing more than $500 million or $100 million of each, respectively.