Maria Castañón Moats is a Leader, Paul DeNicola is a Principal, and Catie Hall is a Director at the Governance Insights Center, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on their PwC memorandum.

Introduction

A widely accepted notion is that corporate boards function like well-oiled machines. And why shouldn’t they? At their core, boards are more than a group of highly qualified individuals — they are sophisticated teams, assembled to work together smoothly while bringing diversity of thought, expertise and experience to their oversight role.

Boards are largely made up of executives, industry veterans and subject matter experts with decades of business experience, and they have the support of skilled management teams and access to numerous advisors, to assist them in their oversight role. Directors certainly know how to work in high-level teams. They’ve done it their entire careers.

But problematic group dynamics can derail all kinds of teams, and boards are no exception. For example, boards can easily find themselves mired in ruts, following comfortably familiar patterns that can lead to ineffective oversight. Directors brought onto boards for their creativity and independence may find themselves in a boardroom culture that pushes them to be deferential and disinclined to challenge the status quo. Reaching consensus may become the goal more than offering input and solutions; consequently, board members known for rationality and agility can become irrational and obstinate.

The good news: board culture doesn’t have to become dysfunctional. Boards can take proactive steps to resolve problems and maintain effectiveness. But this requires directors to be conscious of the dynamics of group behavior — the psychology of the boardroom. It requires them to consider some key questions:

- How does this board respond when we feel under threat?

- What are we inclined to do when things are not working out as anticipated? Do we double down?

- Do we rationalize our past decisions? Do we permit the company to continue to pursue strategies that are not working — or “throw good money after bad” — because we can’t accept that we made the wrong call?

- Is our board composition driven by finding the “smartest person” or a “good fit”? Do we assume that assembling directors with first-rate résumés will naturally produce an effective board?

- Is our boardroom a place where healthy debate and dissenting views are welcomed? Or is departing from the consensus view a one-way ticket to marginalization?

- Is there appropriate understanding of the oversight role of the board versus the role of management?

Four behavioral factors undermining board effectiveness

In our experience, there are four behavioral factors that routinely undermine effective board culture and performance. Boards may:

Factor 1: Threat rigidity

Fall prey to threat rigidity when faced with a crisis

Factor 2: Escalation of commitment

Become entrapped by escalation of commitment when things don’t go as planned

Factor 3: Underestimating collective intelligence

Fail to build the interpersonal dynamics that enable collective intelligence

Factor 4: Lack of psychological safety in the boardroom

Create psychologically unsafe environments that entrench conformity

Factor 1: Threat rigidity

Boards may become rigid when facing external threats

Corporate directors have been conditioned to take stress in stride. Any executive experienced enough to serve on a board has likely developed techniques to keep their cool and arrive at the next board meeting ready to solve problems.

But increasingly, boards are forced to grapple with unanticipated crises far beyond any director’s personal control: cyberattacks, activist shareholders, #MeToo controversies and more. Making consequential decisions under threat conditions has unfortunately become commonplace. And addressing those challenges and crises — under the scrutiny of investors, customers, employees, regulators, communities and the media — can have a real impact on individual performance and team dynamics. 1 Barry Staw, Lance Sandelands and Jane Dutton, “Threat-Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol 26, No. 4, December 1981.

Decades of research have shown that crisis situations systematically and significantly degrade decision-making processes and functioning. Behavioral psychologists call this tendency threat rigidity. Under pressure, teams tend to adopt more rigid group dynamics: they narrow their focus, become less willing to be flexible in decision-making, and reflexively adopt a command-and-control mindset.[1]

Rigid group dynamics aren’t inherently bad. When addressing familiar problems, a limited focus may keep the process streamlined, saving collaborative energy for areas that would benefit more from experimentation and brainstorming. But most board decision-making in uncertain environments — and nearly all environments are uncertain today — demands creativity and adaptive thinking. And that’s exactly what threat rigidity shuts down.

In practice, high-pressure environments tend to generate one or more of the following:

- Narrow thinking. Boards may overvalue proposals that appear to fit established patterns and practices, with predetermined solution steps.

- Conformity. In stressful times, boards may become more likely to shift from seeking consensus to pushing for unanimity. Dissenting views can feel like threats to the board’s goals.

- Deference to leadership. With directors more hesitant to volunteer new ideas, boards may default to authority — deferring to the CEO, board leadership, long-tenured directors or charismatic directors. External advisors may also have an outsized voice.

Research also shows that anxiety makes people more risk-averse,[2] so it’s no surprise that a board facing pressure may aim to alleviate anxiety by driving toward safe, familiar, tried solutions.

Case study

Shareholder activism and threat rigidity

One situation in which threat rigidity may come into play is if shareholder activists take an ownership position in a company and make demands for change. Some boards may respond by hunkering down and becoming resistant to any efforts at engagement. But a more productive strategy would begin with directors being willing to listen with an open mind — and to revisit their own assumptions — as no one has a monopoly on good ideas. Viewing an activist situation as an opportunity to hear other perspectives, rather than only a threat, may feel counterintuitive but could lead to a better outcome. And that outcome may in fact include making some of the changes activists propose.

Next steps

How to minimize threat rigidity

Threat rigidity may be reflexive, but that doesn’t mean a board needs to be paralyzed. Boards can retain their ability to solve problems with creativity and agility under pressure by implementing practices like:

- Tasking directors who have particularly relevant expertise with taking a leadership role in those discussions, encouraging them to challenge the consensus view.

- Listening to all independent board members’ perspectives and providing them the opportunity to ask questions prior to voting on any significant action.

- Mandating development and discussion of potential alternatives to avoid defaulting to the first, most obvious solution.

- Engaging external advisors or other subject matter experts to participate in discussions, explicitly to help challenge assumptions and broaden discussions.

Factor 2: Escalation of commitment

Boards may not be able to admit they were wrong, so they double down

Sometimes it doesn’t matter whether a course of action is paying off — people may double down regardless. They may invest more time and resources into a failing endeavor, long past the point at which they should move on from it.

Part of the problem is a reluctance to acknowledge, or even see, when a decision, project or action needs a course correction. It’s hard to change lenses and view a situation from an entirely fresh perspective — after all, calling for a new direction suggests that one’s initial decision was faulty. In a boardroom, with directors taking ownership of high-stakes decisions and the results, it should be no surprise that individuals may argue for staying the course, even when that position undermines long-term success.

Behavioral scientists call this tendency escalation of commitment. Boards may be driven to maintain their commitments to losing courses of action out of desire to justify previous investments, maintain a positive self-image or avoid admitting failure.[3]

There are various behavioral factors that may make a director’s initial commitment to a course of action stronger no matter what happens later.

- When our actions lead to an unexpected negative outcome, we will often change our attitude toward it to justify the earlier decision we made. People tend to find that an inconsistency in an action and outcome can be uncomfortable, and to help ease the discomfort we change our initial evaluation.

- We may fall prey to confirmation bias — the tendency to seek out and interpret data to support our existing beliefs. Especially if an outcome is looking unfavorable, we often selectively seek out information that supports our stance while ignoring anything that discredits it. We unconsciously cherry-pick information that makes our decision seem like a good one while minimizing evidence that suggests we made the wrong choice.

- Diminishing returns from a strategy don’t necessarily weaken advocates’ commitment to that strategy. Especially if a decline in rewards — sales, profits, innovation, etc. — has been slow and irregular, one may advocate a continued push forward. Gradual declines with occasional spikes may offer false hope that the trendline will reverse.

- Culturally, we associate and reward persistence (“staying the course,” “weathering the storm”) with strong leadership. If people see tenacity as a sign of leadership and withdrawal as a sign of weakness — and research suggests that leadership is generally viewed in exactly that way — why would they expect board members to change course and acknowledge defeat?

Case study

M&A oversight and escalation of commitment

Consider a company that insists on moving forward with an acquisition even as due diligence raises a series of red flags or as market conditions change. Some directors, having advocated to greenlight the transaction, may stick with that assessment despite the evidence, deferring to management’s sunk-cost argument rather than calling for a pause. After all, that might suggest, uncomfortably, that the original view was made in error. The classic “falling in love with a deal” problem is rife with the problems of commitment escalation.

Next steps

How to avoid escalation of commitment

Every boardroom faces the potential problem of escalation of commitment, as management or directors defend past decisions. But boards don’t need to accept the status quo. Some ways that a board can move beyond the impulse to persist and retain the ability to course-correct are as follows.

- Make explicitly clear that changing course based on new information is not only acceptable but laudable. Understanding, recognizing, and encouraging management and the board to demonstrate flexibility — and to learn from mistakes — can help to avoid future escalation of commitment.

- Work to undercut the assumption that colleagues will inherently think less of someone who reverses course, even if decisions have led to negative outcomes. Notwithstanding views of “strong leadership,” people tend to have more respect for those who candidly admit error.

- Emphasize to management teams that there will be little reputational penalty for advocacy of policies and projects that ultimately require pivoting. Fear of the costs of failure is a primary cause of overcommitment, as champions double down on diminishing returns in hopes of reversal.

Factor 3: Underestimating collective intelligence

The traditional board composition calculus may not account for intangibles

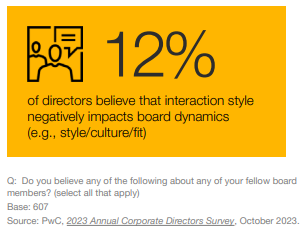

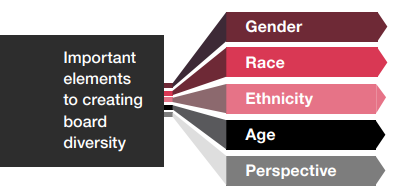

We have found that directors generally recognize the benefits of board diversity. Our research shows that strong majorities agree that gender, race, ethnicity, age and perspective are important to creating diversity of thought in the boardroom.[4]

While achieving the right mix of background and competencies is important for board effectiveness, research also shows that is only part of the equation. There are other, unobservable aspects of board composition.

These hidden aspects were evidenced by researchers who systematically examined characteristics of teams that perform well together; they revealed the crucial role of certain “group norms,” the unwritten rules guiding collaboration, that led to a higher team problem-solving capability — or a higher level of collective intelligence.

What are the norms that matter for team performance? And how can this be applied to the boardroom?

- Conversational turn-taking. Teams with more equal distribution in speaking time at meetings perform better than those in which a few people dominate the conversation. Some boards are naturally equitable, with an open and collaborative culture allowing everyone room to speak; others need board leadership to encourage balanced participation and ensure that valuable voices and viewpoints aren’t silenced.

- Social sensitivity. Teams tend to perform better when members have a greater ability to read each other’s facial expressions, body language and tone of voice. For example, teams with greater sensitivity toward colleagues are able to recognize when someone is feeling upset or left out. Sensitivity to the unspoken social dynamics of the boardroom leads to higher bandwidth collaboration, allowing directors to “read the room” and respond intuitively to changes in their colleagues’ sentiment or focus. Unsurprisingly, this tends to result in better decisions.[5]

It turns out that the right norms can raise a group’s performance regardless of what the goal is, while the wrong norms can derail performance even if all members are exceptionally bright. Said simply, a boardroom with the smartest people doesn’t guarantee a better functioning board or better oversight.

How can boards establish norms and get them to stick? Board leadership should set guidelines that encourage high-bandwidth communication — for example, face-to-face communication that allows for richer exchange of information through body language and facial cues, or synchronous communication that allows for spontaneity and immediate feedback — with plenty of active listening and conversational turn-taking.

These norms can contribute to a board culture characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect. A board with strong social cohesion — an emotional closeness that allows coordination without needing to explicitly communicate — can function more creatively and effectively.

Case study

Collective intelligence

Any veteran of high-stakes board meetings can easily conjure an example of an atmosphere that’s not only unpleasant but counterproductive. Think of a board meeting in which one director dominates, setting the tone and agenda in pushing a particular view, confident in his or her ability to steamroll colleagues and insistent on having the last word in every discussion. Everyone leaves the room less confident than they entered in both the decisions and each other.

Next steps

How to boost collective intelligence

The good news: it’s possible to increase your board’s collective intelligence, both through individual improvement and in the director recruitment process.

- Expand the group of directors involved in the interview process. Typically, the nominating/ governance committee is tasked with recruiting new board members. Bringing in additional perspectives could help identify candidates with greater social sensitivity.

- Make the interview process more focused on behaviors. Don’t just ask questions: present candidates with a real scenario they might face as a director, and observe their problem-solving skills and overall approach.

- Focus on board culture as part of the annual offsite. Offsites are a great way to spend quality time talking as a group about the organization’s strategic priorities and challenges. Carve out time to refine the board’s problem-solving style — through a facilitated exercise, for example. But also leave room for directors to connect without structure or agenda

Of course, team dynamics have always been a factor when considering nominations to any board. But it’s worth paying closer attention to how new directors’ personalities might fit into existing dynamics. The goal should be to strengthen collective intelligence — and boards’ comfort with open discussion of new ideas — by boosting social sensitivity and encouraging conversational turn-taking behavior

Factor 4: Lack of psychological safety in the boardroom

Boardroom culture may discourage dissent, and directors may not be comfortable speaking up

Directors being able to offer considered, constructive input depends on their feeling that the environment is safe and comfortable. A boardroom environment that’s fraught and competitive, in which people feel as though others are hypercritical, hinders the free exchange of ideas, concerns and questions — and consequently, overall effectiveness. Willingness to engage in interpersonal risk-taking is critical to open discussion.

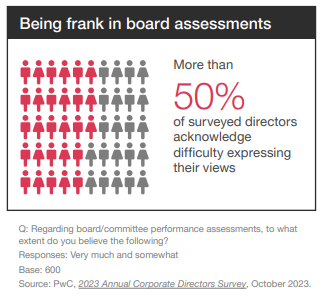

When a boardroom lacks a sense of psychological safety, directors feel uncomfortable speaking up and offering viewpoints that might be unpopular. Other board members’ actions, words and subtle cues can suppress the willingness to share the kind of creative opinions essential to developing comprehensive solutions. A boardroom that is psychologically safe is one with a shared belief that directors can dissent or voice imaginative ideas without facing humiliation.[6] Research suggests that psychological safety is a key differentiator in team performance. One study found that, counterintuitively, higher-performing teams reported more errors than others; the difference was that the high performers openly discussed the errors and how to prevent them in the future. Comfort in engaging in difficult conversations directly drove continuous improvement.[7] In the boardroom today, more than half of surveyed directors acknowledge difficulty frankly expressing their views in board assessments,[8] suggesting reluctance to engage in conversations that could drive improvement and overall communication between directors.

Psychological safety is a prerequisite to a board fulfilling its oversight responsibilities. Directors who feel that they face high levels of interpersonal risk may be far less willing to volunteer new ideas or voice effective challenges, let alone dissent. And that can steer leaders toward making decisions based on incomplete information and the overall board toward approving the safest (but not necessarily the best) solutions.

Psychological safety is also a strong predictor of a board’s ability to learn over time and to self-correct after making choices and decisions that didn’t pan out. Research suggests that a safe environment can help a team solve complex problems by facilitating members’ voluntary contribution of ideas and actions — and can aid the “unfreezing” process required for change.[9]

More broadly, a board that models open communication and decision-making can aid any C-suite’s efforts to create a similar environment across the organization. As many studies have shown, when employees feel as though they can voice their concerns freely, organizations see increased retention and stronger performance. Business units whose employees feel safe offering input tend to have better financial and operational results.

Case study

New directors and psychological safety

New directors quickly gauge the degree of psychological safety in a boardroom. But being the new kid on the block can be intimidating, even for seasoned executives, with fresh arrivals taking a few meetings to assess the existing board’s rhythms and ways of working. Who are the dominant personalities? What is the style of board leadership? How much does this board value diversity of perspective? Boards should be particularly attentive in the first few meetings of a new director’s tenure to model behavior that engenders psychological safety — which will ultimately lead to greater board effectiveness.

Next steps

How to create psychological safety

A board can take concrete steps to boost an individual director’s sense of psychological safety and increase interpersonal risk-taking. But instilling those beliefs and behaviors isn’t necessarily easy.

- Work to build a boardroom environment in which each director feels comfortable and confident in openly sharing ideas and opposing the status quo; this aims to support an increased flow in conversation, raising fresh ideas and views. Protect individuals who challenge the prevailing view.

- Failure can be a learning tool rather than an opportunity for derision and ridicule. Continue to show appreciation for all ideas and views, whether implemented or not. Boards should be open to reversing course or shutting down projects, reinforcing the value of risk-taking and the acceptance of failure.

Action items moving forward

Board assessments

- Make behavioral questions a greater part of assessment surveys. Assessments should provide insights on how directors individually and collectively contribute to the effectiveness of the board. So revisit the questions being asked in assessments. Consider the question style (open-ended versus closed) and the type (practices versus behavioral).

- Provide continuous feedback. Regardless of the approach the board takes to its annual assessment, board leadership should provide continuous feedback to every individual director, and tangible actions should result from the assessment(s). Aggregate results presented at a board meeting are insufficient.

- Conduct individual director assessments. A growing number of boards — 47% of the S&P 500[10] — report doing some sort of assessment of individual director performance. We think this is leading practice because individual assessments provide information about what each director contributes and what value each brings to the boardroom. These insights outweigh fears of a potential negative impact on collegiality.

- Periodically use an outside facilitator for the assessment. The use of a third party to perform a board effectiveness assessment every few years can provide nuanced perspectives that may not be possible with management and board facilitation. Outside facilitators can also assist in formalizing a road map of action items for the board moving forward. Recognizing the additional time and expense involved, a triennial approach may make sense.

Board composition and recruitment

- Move beyond traditional director interviews. Consider behavioral questions and even tabletop exercises to simulate real-life scenarios directors may face in board roles.

- Create a pipeline for board succession planning. Identify three to four potential candidates with whom the board can develop relationships over a longer period of time for consideration as future board members.

- Expand the group of directors that interview new candidates. Don’t default to only the nominating/governance committees or the board chair/independent lead director as interviewers.

- Formalize a mentoring program. Pair each new board member with a more tenured director to help integrate newer directors into the board culture.

- Get feedback on onboarding from newer directors. Ask directors who have joined over the last one or two years how their onboarding helped prepare them to serve on this particular board. What would have helped them prepare for and flourish in the existing culture? Use their insights to adjust existing onboarding programs

Board leadership

- Reconsider the intangibles of the lead director and committee chairs. It’s not just about having the right experience or credentials. Effective board leaders drive the board’s relationship with management, conduct efficient meetings, solicit dissenting views and build consensus. They must be able to facilitate important discussions among board members, listen to all voices and deliver difficult messages.

- Reconsider whether your board leadership structure still works. Our research shows that directors are more likely to have difficulty expressing a dissenting view when there is a combined chair/CEO.[11] Having an independent chair may allow the CEO to focus on that role and could help remove some natural tension.

- Set the right tone at the top. Tone from the top starts with the chair/independent lead director. Make it clear that changing course on decisions is welcomed, mistakes are opportunities and respect is based on a collective set of experiences rather than avoidance of missteps.

Board meeting practices

- Test your response to a crisis. Use tabletop exercises that the board would typically conduct — for example, crisis/breach response — and assess not only for alignment to the company’s response plans and processes but for how directors act under pressure.

- Leverage the strategy offsite. Use strategy offsites to refine and enhance board culture and dynamics through social time as well as behavioral exercises. Don’t focus on only the structured agenda.

- Assign a devil’s advocate. Always present opposing views, even if the board is largely in agreement with a decision to act one way or another. Alternatively, mandate development and discussion of potential alternatives for all critical decisions.

- Pay attention to turn-taking. Discussion of critical topics should involve directors taking turns weighing in and giving everyone the opportunity to air views. Directors with relevant experience on a topic can “own” the agenda topic. This typically requires a strong chair/lead director.

Endnotes

1Barry Staw, Lance Sandelands and Jane Dutton, “Threat-Rigidity Effects in Organizational Behavior: A Multilevel Analysis,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol 26, No. 4, December 1981.(go back)

2Janka Stoker, Harry Garretsen and Dimitrios Soudis, “Tightening the leash after a threat: A multi-level event study on leadership behavior following the financial crisis,” The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 2, April 2019.(go back)

3Barry Staw, “Knee-deep in the big muddy: a study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, Vol. 16, No. 1, June 1976.(go back)

4PwC, 2022 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, October 2022.(go back)

5Anita Woolley, Ishani Aggarwal and Thomas Malone, “Collective Intelligence and Group Performance,” Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 24, No. 6, December 2015.(go back)

6Amy Edmondson and Zhike Lei, “Psychological Safety: The History, Renaissance, and Future of an Interpersonal Construct,” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, Vol. 1, March 2014.(go back)

7Amy Edmondson, “Learning from Mistakes Is Easier Said than Done: Group and Organizational Influences on the Detection and Correction of Human Error,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 32, No. 1, March 1996.(go back)

8PwC, 2023 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, October 2023.(go back)

9Edgar Schein and Warren Bennis, “Personal and organizational change through group methods: The laboratory approach,” New York, NY, 1965.(go back)

10Spencer Stuart, 2023 U.S. Spencer Stuart Board Index, September 2023.(go back)

11PwC, 2023 Annual Corporate Directors Survey, October 2023.(go back)

Print

Print