Eli Kasargod-Staub is Executive Director and Kimberly Gladman is a Senior Sustainability Fellow at Majority Action. This post is based on their Majority Action report. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes Socially Responsible Firms by Alan Ferrell, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog (discussed on the Forum here) and Social Responsibility Resolutions by Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here).

In recent years, institutional investors worldwide have won substantial advances in corporate disclosures and engagement on climate change. Companies across a range of industries have set emissions reductions targets, undertaken scenario planning, and made meaningful disclosures of climate-related risks. Moreover, despite the Trump Administration’s announced plan to withdraw from the 2015 Paris Agreement, investors joined with mayors, governors, and business leaders across the United States in the “We Are Still In” coalition, re-doubling their commitment to meeting the agreement’s goals of keeping warming to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C.

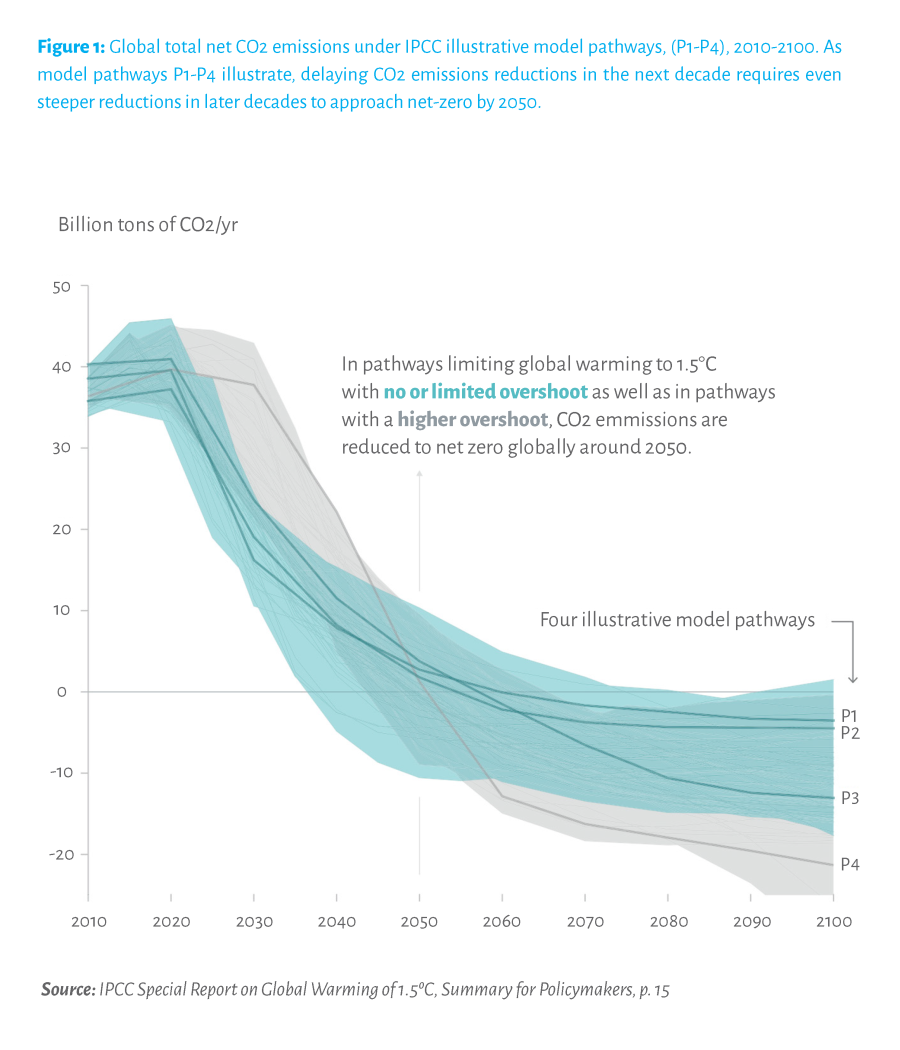

Unfortunately, current global commitments and actions still put us on track for potentially catastrophic temperature rise. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the world’s most authoritative global body on climate science, and in October 2018 it published a landmark report (Global Warming of 1.5°C) in response to an invitation from the parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement. The report demonstrates that global carbon emissions must decline by nearly half to 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050 to have at least a 50% chance of limiting warming to 1.5°C and avoiding the worst effects of climate change. If we fail to do so, humanity will face extreme changes to weather patterns and ecosystems, massive economic damage, and unprecedented social and political upheaval. For long-term investors, these risks are large, quantifiable, and cannot be diversified away.

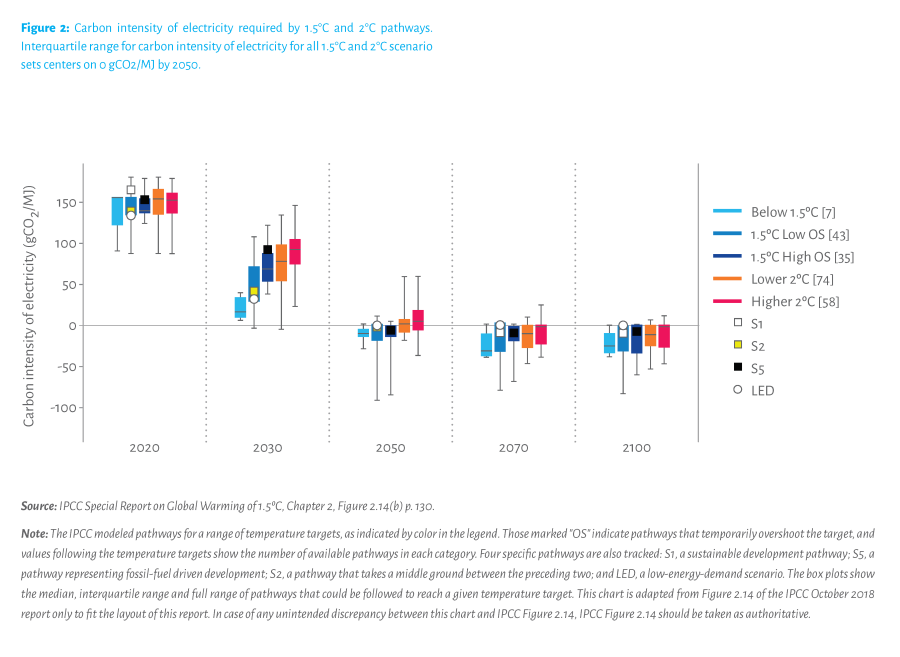

According to the IPCC, global decarbonization of electricity generation is central to achieving net-zero carbon emissions economy-wide by 2050, and is a robust feature of both 1.5°C and 2°C pathways. Electricity decarbonization delivers double benefit, both by eliminating the sector’s own substantial emissions and by unlocking the benefits of electrifying other sectors, such as transportation. Failure to decarbonize poses material risks for electric utility investors. Fortunately, as this report outlines, decarbonization can also create significant new opportunities for the electric power sector, as electrification of the economy can drive substantial demand growth just as the costs of renewable energy generation and battery storage are plummeting. Investors therefore have both a fiduciary interest and obligation to ensure that the electric utility industry is on track to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest.

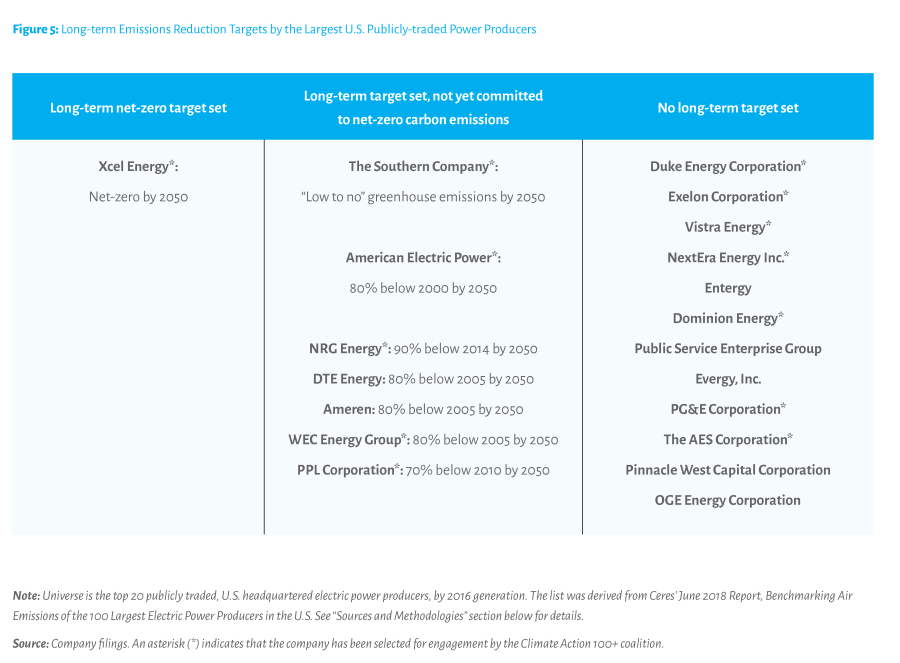

With these imperatives, risks, and opportunities in mind, this report surveys the decarbonization commitments and corporate governance of the twenty largest U.S. publicly traded power generators, which collectively account for nearly 50% of the electric power sector’s CO2 emissions. Of these twenty, only one (Xcel Energy) has committed to a net-zero by 2050 target. Seven others have set long-term targets that are not yet in line with the IPCC’s recommendations, and the remaining twelve have not set any long-term target at all. None of the companies can yet demonstrate that their capital expenditures are in line with achieving a net-zero target, and many have invested heavily in policy-related activity opposing efforts to mitigate climate change.

As a result, this report recommends that investors call upon companies in the power sector to commit to a target of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest, and making that commitment within the next six months. Consistent with the framework of the Climate Action 100+, a $33 trillion global investor network promoting corporate action on climate change, we further recommend a set of governance mechanisms that utilities should adopt over the next year to ensure that this target will be met. These include board-level oversight of the net-zero carbon transition, detailed transition planning disclosures, tying executive compensation to decarbonization benchmarks, and the alignment of policy influence toward achieving the net-zero target. Finally, this report recommends that investors consider aligning their proxy voting to ensure that utility industry directors and executives are exercising responsibility and leadership in this transition.

Investor Risks and Opportunities in the Context of Deep Decarbonization of Electricity Generation

The October 2018 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could not be clearer: we are on track to climate disaster, and we have just a decade to avert the worst of it. Climate change will impose immense costs on all parts of society and poses specific risks to long-term investors worldwide. These include extreme weather events, rising pollution-related risks to human health, and biodiversity collapse, with severe political instability, famine, disease, and mass migration posing material risks to investors and ultimately, the habitability of the planet. These risks are large, quantifiable, and undiversifiable, with estimates of economic cost of only limiting warming to 3°C reaching 15-25% of per capita output. Seemingly small changes in warming can have drastic effects; limiting warming to 1.5°C is estimated to accrue over $20 trillion in benefit by the end of the century compared to allowing warming of 2°C.

According to the IPCC, achieving at minimum a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires cutting carbon emissions nearly in half across the entire global economy by 2030, and then reaching net-zero emissions worldwide by 2050 (see Figure 1). Achieving this will require immediate action. Unfortunately, even after a more than a decade of efforts to reduce carbon emissions in the U.S., preliminary data shows a 3.4% increase in overall carbon emissions for 2018. Carbon emissions from electricity generation increased 1.9%, demonstrating the limitations of relying on a transition to natural gas generation to deliver the carbon reductions required. The IPCC’s report makes clear that decarbonization of electricity must be the centerpiece of any plan to avert climate catastrophe. It explores scenarios and pathways for the transformation of our energy system that are consistent with a 1.5°C temperature rise. As the IPCC report states, “A robust feature of 1.5°C-consistent pathways […] is a virtually full decarbonization of the power sector around mid-century, a feature shared with 2°C-consistent pathways. The additional emissions reductions in 1.5°C-consistent compared to 2°C-consistent pathways come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors.” (See Figure 2.)

The power sector is the second largest greenhouse gas emitting sector in the U.S., contributing 28.4% of the country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. Just 20 publicly-traded companies account for 47%—nearly half—of the sector’s carbon emissions. Despite advances in renewable energy technology and deployment, approximately 68% of electricity in the U.S. is still generated from fossil fuels, mostly coal and gas. Eliminating emissions in the electricity sector is also crucial to decarbonizing other sectors such as transportation, which is currently the largest source (28.5%) of carbon emissions in the U.S. According to the IPCC, transportation will need to be run substantially on zero-carbon emissions electricity in order to achieve sufficient carbon reductions in that sector, even with significant electrification and efficiency gains.

Decarbonization of the economy and electrification of other sectors create unprecedented opportunities and challenges for utilities and their investors. Utilities are facing stagnant demand, with increases in usage from economic growth offset by increased efficiencies and development of distributed generation. Economy-wide decarbonization has the potential to drive a dramatic expansion of electricity usage as transportation, heating, and industrial activities are electrified. According to the IPCC, as these sectors shift away from fossil fuels, the projected share of electricity in 2050 energy consumption could more than double from 2010 levels (see Figure 3). Globally, electric vehicles could add around 2,000 TWh of new electricity demand by 2040, and nearly 3,500 TWh by 2050.

The transition to capital intensive, low operating cost, renewable generation can potentially support higher earnings growth, particularly for regulated utilities. While regulated utilities can earn a rate of return on eligible and approved capital investments, in most cases they earn no profit margin on fuel and other operating costs. In describing its recently announced net-zero commitment, Xcel Energy calls its replacement of fossil generation with wind and solar installations a “steel for fuel” trade and sees it as a win-win for the utility and consumers. Consumers benefit from lower rates from renewables with low operating costs. At the same time, the new generation is more capital intensive than the assets it replaces, creating greater potential for earnings growth.

While the scale and speed of the transformation required to decarbonize the electric power sector are unprecedented, there are many potential pathways available to pursue that target. While the IPCC report describes a “strong upscaling of renewables,” achieving net-zero carbon emissions does not require that 100% of electricity will come from renewable sources. Though not without controversy, there may remain a significant role for hydropower and nuclear, and potentially fossil fuel generation with carbon capture and storage as well, if such technologies can be proven and commercialized. Different utilities will have different opportunities based on their regional renewable resources, existing generation portfolio, integration with interstate electricity markets, and consumer needs.

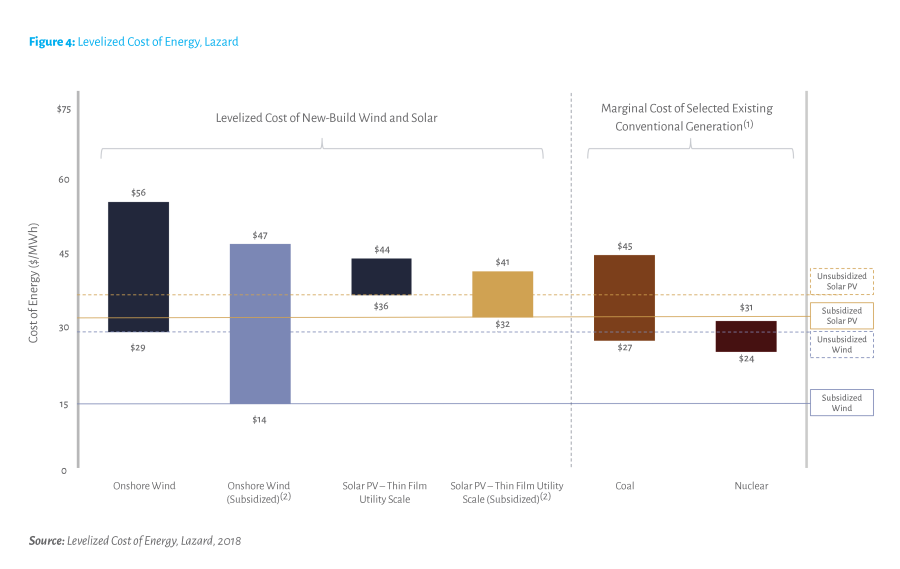

Fortunately, never before have the economics of a transition to net-zero emissions been so favorable.Across the board, existing commercial renewable technologies have fallen radically in cost in recent years. Since 2009, the levelized costs of utility-scale wind and solar have dropped 69% and 88% respectively, placing them at or below the marginal cost of coal and gas generation. According to research from Lazard, in some circumstances, it is already cheaper to build new wind generation than to continue to operate fully depreciated coal-fired generation (see Figure 4). New onshore wind generation is also now cost-competitive with natural gas, costing $29-56 per MWh, compared with $41-74 per MWh for new combined cycle gas generation. A 2016 MIT study noted that many analysts expect the installed cost of utility-scale solar PV to fall below $1 per watt by 2020, and foresee a further 24% to 30% reduction in wind energy costs by 2030.

Technology to support grid flexibility and to manage the variability of renewable generation is also expanding in scope and falling in cost. Deployed battery storage in the U.S. is already expected to grow from 774 MWh to 11,700 MWh by 2023. By 2030, the installed costs of battery storage systems could fall by 50-66%, and as a consequence, battery storage in stationary applications is poised to grow at least 17-fold by 2030. Bloomberg New Energy Finance already expects $620 billion will be invested in the global energy storage market by 2040, to provide more than 900 GW of capacity to support the integration of variable wind and solar generation.

While decarbonization is more feasible than ever, planning backwards from a net-zero target is critical, as pursuing partial or step-wise targets could lead a utility to make substantially different near-term investment decisions and capital expenditure allocations than they would if pursuing deep decarbonization. As researchers with the Energy Innovation Reform Project noted, “there is a strong consensus in the literature that reaching near-zero emissions is much more challenging—and may require a very different mix of resources—than comparatively modest emissions reductions (50-70% or less).” Planning and policy measures should therefore focus on long-term objectives (near-zero emissions) in order to avoid costly lock-in of suboptimal resources.” In particular, this incremental approach may result in overbuilding unabated natural gas infrastructure that is incompatible with a net-zero future.

Unfortunately, U.S. publicly traded utilities are not on track to decarbonization. This report surveys the decarbonization commitments of each of the twenty largest publicly traded U.S. power producers by generation (see Figure 5). Only one, Xcel Energy, has made a commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Of the remaining nineteen, just seven have set some form of long-term partial decarbonization commitment, with significant variability among them on targets, base years, and specificity. Twelve have made no long-term commitments at all. In addition, many utilities have actively engaged in political and lobbying activity to oppose policy initiatives intended to combat climate change.

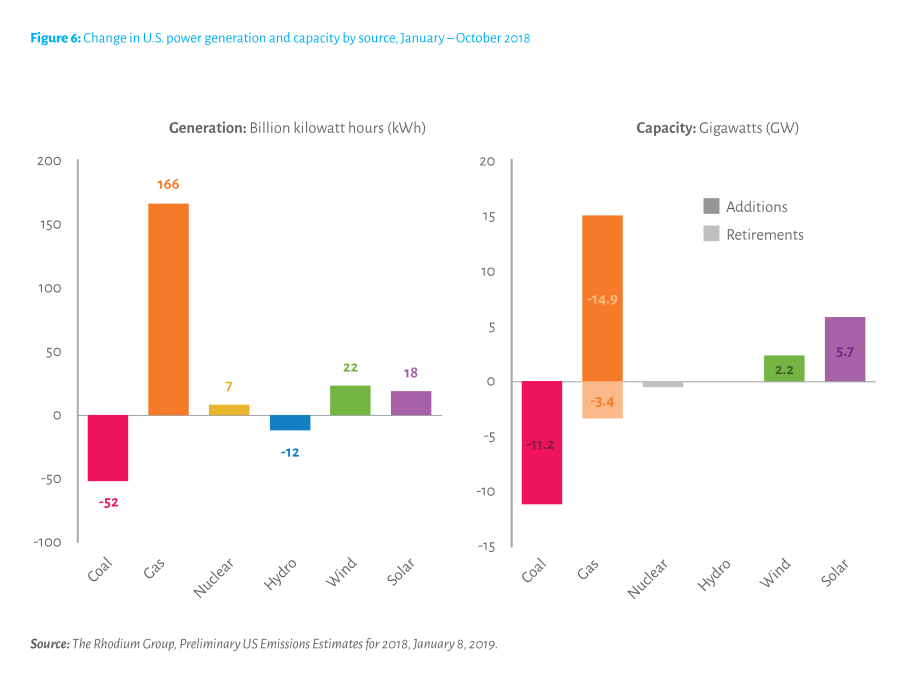

Moreover, emissions reductions progress that has come from replacing coal with natural gas has left the electricity system dependent on fossil fuel generation whose emissions we will still need to reduce. According to data from the Rhodium Group, though power generators have been retiring coal plants, natural gas generation increased four times the combined growth in wind and solar in 2018 (see Figure 6).

An October 2018 report by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), an industry group, may illustrate a divergence in assumptions and orientation to the climate crisis between the industry and many informed observers outside it. The EPRI report, which does not incorporate the IPCC’s October 2018 findings, appears to critique the 2015 Paris Agreement targets of limiting warming to 1.5°C – 2°C as not “scientifically-derived,” despite substantial scientific research illustrating the potentially catastrophic harm and cost of exceeding such thresholds. As the report states: “Given the challenges of limiting warming to 2°C— the increasing cost of emissions reductions, global coordination, and rapid significant technology deployments—as well as 2°C not being a scientific threshold, it is [sic] pragmatic to begin asking about the implications of limiting warming to 2.1°C, 2.2°C, or 2.5°C versus 2°C, 1.9°C, 1.8°C, or 1.5°C?”

In addition to portfolio-wide risks from climate change, investors face a set of sector and company-specific risks if utilities fail to commit to decarbonization. These include:

Policy and Regulatory Risks: In response to mounting pressure at the state level to respond to climate change, governors representing nearly a third of the population of the U.S. have established or declared intentions to achieve ambitious electricity decarbonization targets, often even sooner than 2050. For example, California has legislated fully carbon-free electricity by 2045, and Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York has pledged to bring the state 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040. Failure to proactively embrace net-zero targets therefore leaves utilities vulnerable to the consequences of potentially dramatic policy shifts. Even for utilities operating in states without such targets, utilities may miss out on opportunities to participate in markets that have stricter targets than their home states.

Financial Risks: Without a strong commitment to reaching net-zero emissions, utilities risk overbuilding long-lived fossil fuel generation capacity that will be impossible to keep operating if a company is going to decarbonize by 2050, either in pursuit of its own net-zero target or if forced to by policy changes. Flawed capital expenditure plans in the coming years—including those arising from capital expenditures in pursuit of partial or stepwise decarbonization commitments—could lead to costly retrofits and asset write-downs to achieve net-zero emissions, particularly if regulators and elected officials prevent such unnecessary costs from being pushed onto consumers. Even if utilities are successfully able to pass these costs onto customers, doing so risks customer backlash and subsequent deterioration of regulatory relationships.

Competitive Risks: Local governments may act to separate their local electric system from a utility’s network and to create a municipal utility, as is now happening in cities like Boulder, Colorado, while retail customers may increasingly choose local, carbon-free, or distributed generation.

Physical Risks: Climate change is exacerbating the risks of natural disasters that can cause many billions of dollars in damage to electricity infrastructure, with utilities in the southeast of the U.S. facing billions in recovery costs after historic hurricane damage. Though decarbonization by individual companies cannot eliminate climate change-driven physical risks, investors in the electric power sector are highly exposed to harmful events driven or exacerbated by climate change, as exemplified by PG&E declaring bankruptcy following the 2018 wildfires in California.

While the pathway to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 at the latest will likely look different for each utility, every company will require significant realignment of corporate strategies, capital expenditures, regulatory engagement, and political and lobbying activity. Unfortunately, U.S. publicly traded utilities do not have governance structures in place to catalyze and oversee the transition to net-zero emissions (see Appendix B of the complete publication for greater detail). Moreover, as far as can be discerned from the biographies of corporate directors printed in proxy statements, few directors on utility boards have expertise in climate change issues or renewable energy, or experience in overseeing complex, long-range transformations of business models. In general, boards in this group of companies have less independent leadership than is typical for S&P 500 firms: only 30% of the group (6 of 20) separate the chair and CEO roles, compared to 50% of the index. Incentives for management must also be aligned with strategies to transition to a net-zero carbon emissions future. While many companies incorporate safety and other operational metrics into their executive compensation plans, as of this writing, only one—Xcel Energy—incentivizes executives to pursue emissions reduction targets.

In order to ensure investor confidence in commitments made to reduce carbon emissions, boards must explicitly take responsibility for the net-zero transition, and management must be appropriately incentivized to reach milestones set by working backwards from that target. In addition, for those electric utilities that also own gas distribution and midstream assets, rigorous net-zero scenario planning will be needed to ensure these assets are not stranded as gas generation and use is phased out to reach net-zero emissions. Integrated electric and gas utilities should also play a leadership role in promoting and implementing the electrification of certain gas end uses, such as heating.

Recommendations for Utilities:

A Framework for Responsible Governance of the Net-Zero Transition

Given both the urgency and complexity of the electricity decarbonization transition, it is crucial for electric utilities to commit to a goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 at the latest (See Appendix B). Only by working backwards from this goal will companies in the power sector mitigate the risks and capitalize on the opportunities of decarbonization. Once that baseline commitment is made, every utility board of directors must ensure that this commitment is fully integrated into its corporate decision-making. Consistent with the principles of the Climate Action 100+ (See Appendix C of the complete publication), we recommend that utilities:

- Formally establish that the board of directors is responsible for overseeing execution of the This could occur by forming a decarbonization transition committee of the board. Accordingly, the company must demonstrate how it will access the necessary climate change, decarbonization, and corporate transformation expertise. These responsibilities should cover oversight of the operational and strategic aspects of the transition, compensation practices, and corporate affairs policies, including political spending.

- Develop and publish a detailed transition plan toward achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, with clear near-term benchmarks and plans for 2025 and 2030. The specific transition plan will certainly look different for different utilities, but it must work backward from the net-zero target, detail specific steps in the proposed transition, and incorporate measurable benchmarks.

- Meaningfully incorporate transition milestones into executive compensation A substantial portion of executive compensation must be tied to meeting targets set by the decarbonization transition plan in order to appropriately align incentives.

- Disclose how a utility’s political, lobbying and trade association activities will be brought into alignment with this net-zero Utilities should identify the policy and regulatory reforms needed to achieve the decarbonization transition and disclose how they will align their policy-related activities accordingly. This should include a clear breakdown of how each element of such activity supports the decarbonization strategy.

Recommendations for Investors: The Case for Accountability

For institutional investors with a long time horizon, a key aspect of fiduciary duty is ensuring that the boards of investee companies are competent, independent, and diverse. Investors have an important role to play in ensuring that boards implement structures and processes that will allow them to appropriately oversee the full range of risks facing their businesses, and nominating committees in particular must be held to account for ensuring that boards have the right mix of perspectives and skills to do so. Particularly in times of business model transformation, regular refreshment of the board is important to ensure that the current balance of director experiences and abilities matches the company’s current needs. Institutional investors have an obligation to their beneficiaries to carry out this oversight of corporate boards through monitoring, engagement, and proxy voting.

Indeed, for long-term investors with broad market exposure, voting on the election of corporate directors is the single most direct and important action they can take to convey their views on how a company is being managed to the leaders involved. Increasingly, leading asset owners and asset managers are using their director votes to express concern regarding key aspects of corporate governance. For example, State Street Global Advisors votes against boards with insufficient gender diversity; in 2018 CalPERS voted against 438 directors at 131 companies for such failures as well. The State of Rhode Island opposed directors at over 200 companies in 2018 due to a lack of either gender or racial diversity on the board. An important part of Legal and General Asset Management’s Climate Impact Pledge, moreover, is a commitment to vote against directors at companies that have shown “persistent inaction to address climate risk.”

Commitments of this nature reflect the reality that risks to investors from climate change are material, and both portfolio-wide and company-specific. Consistent with their fiduciary duties, institutional investors can act to ensure that the utilities in which they are invested are planning adequately for a net-zero carbon future, mitigating these risks to investors, and taking full advantage of the opportunities economy-wide decarbonization presents. Achieving net-zero emissions will require company-wide transformation for utilities, for which utility boards of directors bear direct and specific responsibility.

The risks associated with climate change have been well understood for over two decades, and companies have had ample time to evaluate how to bring their operations in line with decarbonization targets. In 2017, investors associated with the Climate Action 100+ coalition sent letters to the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters, calling on them to adopt targets consistent with the Paris Agreement goals of limiting warming to “well below 2 degrees Celsius,” implement a strong governance framework, and provide robust disclosures. The Climate Action 100+ engagement effort covers a majority of the companies analyzed in this report; of those, all but Xcel have thus far failed to adopt such a target.

The Climate Majority Project urges investors to evaluate utility company responses to the climate crisis and the risks their actions or inactions pose to investors, assess whether these companies’ directors are responding responsibly, and express their conclusions through their proxy voting.

Specifically, we recommend that investors consider adopting the following approach to their proxy voting in the electric utility sector:

- Companies should be encouraged to make the net-zero by 2050 commitment within the next six months, and undertake the reforms recommended above within the next year.

- If a utility has failed to make a net-zero commitment and undertake the four core board-level actions and reforms listed above by the time of the 2020 proxy statement, then asset owners and managers should consider voting against the chair of its board of directors (and lead independent director, if applicable) in 2020.

The complete publication, including footnotes and appendix, is available here.

Print

Print