David Woodcock, Shamoil T. Shipchandler, and Joan E. McKown are partners at Jones Day. This post is based on a Jones Day memorandum by Mr. Woodcock, Mr. Shipchandler, Ms. McKown, Henry Klehm III, and Jules Cantor.

In May 2019, the SEC completed its second full year under the stewardship of Chairman Jay Clayton. Unlike the “broken windows” philosophy of Chair Mary Jo White that left little room for interpretation, Chairman Clayton has steadfastly adhered to his focus on “Main Street investors,” which has proven to be a concept that is straightforward in its delivery but difficult to predict in its application. As we have discussed in our previous White Papers, the ideological orientation of the Commission as a whole has been a challenge to ascertain based on several factors, including limitations on its ability to collect disgorgement, constitutional challenges to its administrative procedures, the federal government’s repeated budgetary issues, and the explosive growth of digital asset-based offerings, to name a few.

More specifically, when we try to understand where the Enforcement Division is heading, we examine the nature of cases that it has filed, the remedies that it has obtained and forgone, and the public statements of its Commissioners and Senior Officers, among other factors. But during Chairman Clayton’s tenure, these internally driven factors have been significantly affected, and in many ways overtaken, by outside factors that have never been present before or that have become more pronounced than ever before. For example:

- The average time for the Enforcement Division to open, investigate, and file a case is approximately 24 months, and closer to 36 months for financial reporting and issuer disclosure cases. Given that the statute of limitations begins when conduct leading to a violation begins and not when that conduct is discovered, Kokesh has likely forced the SEC to close cases based solely on an inability to obtain a meaningful remedy.

- According to the SEC’s 2018 Division of Enforcement Annual Report, the Lucia decision “required the Division to divert substantial trial and other resources to older matters, many of which had been substantially resolved prior to the decision.” Diverting those resources to resolve older cases has likely forced the SEC to make resource-based decisions to close other

- According to Chairman Clayton, due to the federal budgetary issues, “Commission staffing is down more than 400 authorized positions compared to fiscal year 2016,” with the Enforcement Division itself reduced by 10 percent. While the hiring freeze has now been lifted, it will take the Commission time to hire and train new employees.

- In his 2015 confirmation hearing, Chairman Clayton was neither asked about nor opined on digital assets and blockchain technology. ICO activity then spiked in late 2017, doubled again in 2018, and forced an allocation of resources and immediate response from the SEC’s policymaking arms and Enforcement Division, including the creation of a dedicated Cyber Unit for these and other issues.

While these issues are not specific to financial reporting and issuer disclosure matters, they certainly affect the Commission’s ability to allocate resources to investigate and file such cases.

Nevertheless, while these issues continue to affect the Enforcement Division, there do appear to be certain commonalities in the cases that we see the Commission choose to file. For example:

- Enforcement Division decision-making continues to become more centralized, with more operational oversight coming from headquarters at each stage of an investigation’s life cycle, including the opening of a matter. While the specialized units continue to separately investigate and file their cases, they are now significantly more involved in cases that originate from the regions, particularly with respect to FCPA and cyber cases.

- There are fewer cases involving public companies, and those that are filed generally do not focus on technical accounting and disclosure issues.

- There remain instances of significant corporate penalties, but those that are imposed are often accompanied by explanations in accompanying press releases that highlight why the penalties were appropriate.

- There remains a clear emphasis on individual accountability and a de facto presumption that recommendations will involve charges against the individuals involved.

- Company compliance structure and commitment to compliance continues to increase in importance, especially in light of the Department of Justice’s April 2019 guidance on the Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs.

We discuss our view of Enforcement’s activity in greater detail below.

Two additional developments that bear watching are the July 8, 2019, confirmation of Allison H. Lee and the tenor and frequency of Commissioner Hester M. Peirce’s speeches. According to her SEC biography, Commissioner Lee served for more than 10 years at the SEC, including as counsel to her predecessor, Commissioner Kara Stein. Much about Commissioner Lee’s specific views are unknown at this time. Conceptually, however, her approach may significantly affect the Enforcement Division.

With a full allotment of Commissioners, Enforcement recommendations need three of five votes to be approved. Because Commissioner Peirce’s “no” rate is higher than the rate at which any other Commissioner votes against recommendations from the Enforcement Division, the Enforcement Division typically looks to build a three-vote coalition from the center with Chairman Clayton and Commissioners Robert J. Jackson, Jr. and Elad L. Roisman. However, if that coalition becomes Chairman Clayton and Commissioners Jackson and Lee, we would expect to see a more aggressive Commission with more receptiveness to corporate penalties, for example.

Commissioner Peirce has become the most prolific speaker of all of the Commissioners, with 10 speeches in 2019 compared to five for Chairman Clayton and two each for Commissioners Jackson and Roisman. Commissioner Peirce was the only Commissioner to make a speech in May, during which she gave five speeches. Thematically, her speeches embrace the concept of lightened regulation but incorporate topics as wide-ranging as digital assets (where she has embraced the moniker “CryptoMom”), and environmental, social, and governance (“ESG”) disclosures. Her individual views on digital assets do not appear to be shared by the Commission; however, her individual views regarding ESG disclosure appear consistent with how the Commission has approached this issue recently.

2019 Enforcement Actions

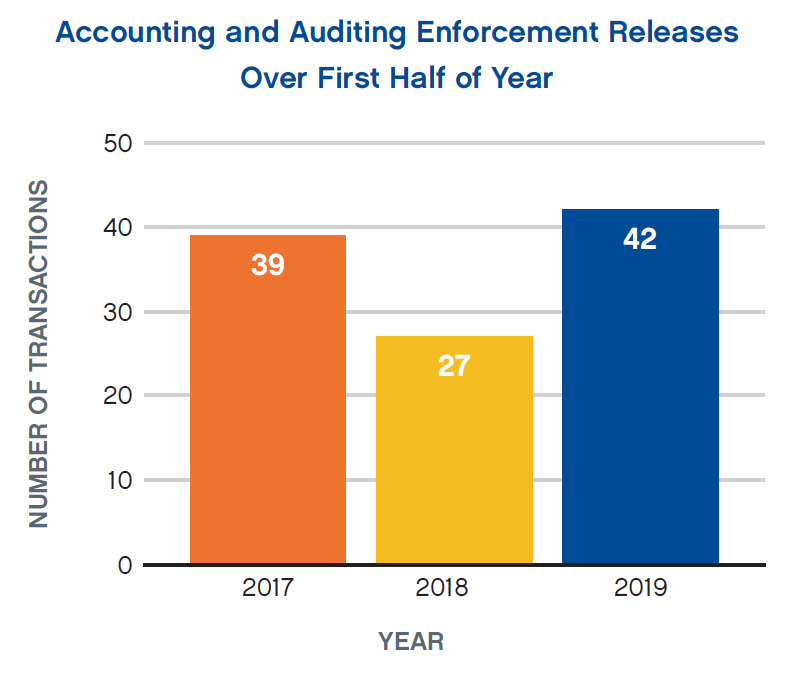

Consistent with Chairman Clayton’s touchstone, the SEC continues to characterize the Enforcement cases it files as relative to protection of “The Retail Investor.” We group the cases filed in the first half of 2019 in the following imperfect categories: (i) material weaknesses in internal controls; (ii) private companies; (iii) accounting fraud; (iv) individual accountability; (v) insider trading; and (vi) auditor independence. The overall numbers are far from complete for 2019, but they appear to be tracking prior years’ results for the same period.

Material Weakness in Internal Controls

In January 2019, the SEC brought coordinated actions against four public company issuers for failure to maintain internal controls over financial reporting (“ICFR”). The SEC mandates that certain issuers establish and maintain ICFR to ensure that financial reporting is reliable because “[a]dequate internal controls are the first line of defense in detecting and preventing material errors or fraud in financial reporting.” According to the SEC, where a company’s ICFR is inadequate, the issuer must disclose the inadequacy and promptly remediate: “Companies cannot hide behind disclosures as a way to meet their ICFR obligations. Disclosure of material weaknesses is not enough without meaningful remediation. We are committed to holding corporations accountable for failing to timely remediate material weaknesses.”

According to the SEC’s orders, the four issuers allegedly disclosed material weaknesses in ICFR from approximately seven to 10 years but did not undertake or undertook ineffective measures to remediate. In some instances, the issuers took months or years to remediate even after being contacted by the SEC.

Enforcement Actions Against Private Companies

The SEC continued enforcement actions against private companies for violating Section 17(a)(2) of the Securities Act, which makes it illegal to engage in any fraudulent practice in the offer and sale of securities, regardless of whether those securities must be registered. In April 2019, the SEC announced a $3 million penalty against a fintech company that offers and sells securities linked to the performance of its consumer credit loans for allegedly miscalculating and materially overstating annualized net returns to retail and other investors. According to the SEC, the company excluded certain nonperforming, charged-off loans from its calculation of annualized net returns that it reported to investors, which led to the company to overstate its annualized net returns.

Accounting and Disclosure Fraud

The SEC brought a settled action against a truckload freight company alleging an accounting fraud by which the company significantly overstated its pre-tax and net income and earnings per share in its public filings. The company arranged to sell more than 1,000 used trucks at inflated prices to a third party, and in exchange bought trucks from the same party at similarly inflated prices. The company then put the trucks on its books at the inflated values it paid—avoiding recognition of least $20 million in losses that it would have recognized had the trucks been sold on the open market. As a result, the SEC alleged that the company overstated its pre-tax income, net income, and earnings per share in its annual report and subsequent public filings. As part of the settlement, the company agreed to a permanent injunction, remedial action to address the material weaknesses in the company’s internal control over financial reporting, and a payment of $7 million in disgorgement.

This is the latest in a growing line of actions brought by the SEC against companies or their executives for committing accounting fraud by entering into sham agreements with third parties. In 2017 and 2018, the SEC brought charges in four different instances against companies that overstated revenue through at least one of the following unlawful accounting practices: (i) issuing false invoices to customers or suppliers; (ii) recognizing revenue for services that had not been performed; (iii) entering into undisclosed side agreements that relieved customers of payment obligations; (iv) inflating prices of products with the agreement to repay the inflated amounts to customers; (v) overstating assets and revenues and understating its liabilities to lessen the impact of executives stealing company money; and (vi) using fraudulent bank statements to show that executives controlled certain entities owned by the company.

The SEC recently charged an automotive manufacturer, two of its subsidiaries, and its former CEO for defrauding investors by making “a series of deceptive claims about the environmental impact of the company’s ‘clean diesel fleet.’” Specifically, the SEC alleged that the automaker “issued more than $13 billion in bonds and asset-backed securities in the U.S. markets at a time when senior executives knew that more than 500,000 vehicles in the United States grossly exceeded legal vehicle emissions limits, exposing the company to massive financial and reputational harm.” According to the SEC, the automaker “made false and misleading statements to investors and underwriters about vehicle quality, environmental compliance, and [its] financial standing,” and thereby “reaped hundreds of millions of dollars in benefit by issuing the securities at more attractive rates for the company.” The SEC complaint seeks permanent injunctions, disgorgement, and civil penalties as remedies. The automaker is challenging the SEC’s claims and has said in prior court filings that the SEC’s lawsuit was “driven by hindsight bias and is an unfortunate example of ‘piling on.’”

Individual Accountability

Regardless of the Commission or political party in power, SEC Enforcement will seek to charge senior-level officers and directors where possible, and this is especially the case in financial reporting and disclosure cases. The number of individuals charged in SEC actions has been steady in the first half of 2019, and there is no indication that the trend will change anytime soon.

- The SEC charged four former executives of a now-bankrupt energy company alleging their participation in disclosure and accounting fraud. The complaint alleged that the defendants allegedly misrepresented the company’s prospects with respect to construction, ownership, and operation of seven combined-heat-and-power plants by falsely valuing a $44 million “Construction in Progress” asset, which constituted more than a 400% inflation and comprised approximately 51% of the energy company’s reported total assets as of March 2014. The complaint, filed in a federal district court in Nevada, charged the defendants with a combination of violations under Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Sections 10(b), 13(a), and 13(b) of the Exchange Act.

- The SEC filed a complaint against a purported online-gaming business and its founder in a federal district court in New York on February 7, 2019, alleging that from at least February 2013 until mid-2017, the founder made misrepresentations to prospective and current investors in the course of raising approximately $9 million from more than 50 investors. The founder allegedly misappropriated at least $1.3 million of these funds to fuel his gambling habit, cover personal expenses, satisfy a prior legal judgment entered against him, and make luxury purchases. The SEC’s complaint charged the defendants with violating Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. It sought permanent injunctions, civil monetary penalties, and disgorgement of ill-gotten monetary gains plus interest. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York initiated parallel criminal proceedings against the founder.

- The SEC filed a complaint in a federal district court in Indiana charging the former CEO and COO of a plastics manufacturer “with concealing from potential buyers [] that their company’s core business model was a sham.” The business model was premised on the company’s ability to use inexpensive recycled and scrap materials to develop high-quality plastics, claiming that it could transform “garbage to gold.” Allegedly, however, the company routinely lied to its customers and falsified test results to suggest that its products complied with important customer specifications. The defendants continued to conceal their fraudulent practice after selling their company to another plastics company, even through the sale of that plastics company to a publicly traded company. The SEC’s complaint charged the defendants with fraud in violation of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, seeking permanent injunctions, disgorgement, civil monetary penalties, and officer-and-director bars.

- The SEC charged the former controller of a New York-based, not-for-profit college with defrauding municipal securities investors by fraudulently misrepresenting the college’s financial condition. When the college came under financial stress, the controller published falsified financial statements that overstated the college’s net assets by almost $34 million. These statements were made available to investors through an online repository and influenced their decisions to invest in bonds. The controller also failed to record unpaid payroll tax liabilities, and he did not assess the collectability of pledged donations that were increasingly unlikely to be received from disgruntled donors. After he was charged with violations of Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, the controller agreed to a partial settlement that would permanently enjoin him from future misconduct, and potential monetary sanctions will be determined at a later date. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York announced parallel criminal charges, to which the controller has pleaded guilty.

- The SEC obtained a final judgment against the former CFO of a publicly traded pharmaceuticals company. The SEC brought suit against the CFO, two other officers, and the company in 2016, alleging that they had defrauded investors by misleading them about the prospect of obtaining FDA approval of the company’s flagship drug. In the final judgment, a federal district court in Massachusetts barred the CFO from serving as an officer or director of a public company for two years, imposed a $120,000 penalty, ordered disgorgement of $5,677 plus prejudgment interest, and enjoined him from further violations of the antifraud provisions of the Securities Act and the Exchange Act.

- The SEC filed a complaint against the founder and former CEO of a mobile payments start-up company in a federal district court in California, alleging that he defrauded investors by grossly overstating the company’s 2013 and 2014 revenues before selling personally owned shares into the private, secondary market. The founder and former CEO allegedly made $14 million from these sales but hid them from the company’s board of directors. After the SEC filed its complaint charging the founder and former CEO with violations of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, he agreed to pay more than $16 million to settle the charges. The SEC also settled a separate proceeding against the company’s former CFO for approximately $420,000. The CFO entered into a cooperation agreement with the SEC after he failed to exercise reasonable care concerning the company’s financial statements and signed transfer agreements that falsely implied that the company’s board of directors had approved the founder and former CEO’s personal sales.

- The SEC filed charges against a now-defunct financial technology firm and two of its executives. The complaint alleged that the CEO/chairman and the executive vice president of sales engaged in a fraudulent accounting scheme that cost investors more than $18 million. Recognizing that the firm was losing money and needed to raise capital to stay in business, the two executives entered into side agreements with the firm’s largest customer. These side agreements gave the customer an unconditional right to cancel in the future, which precludes revenue recognition under GAAP. The two executives ensured that the firm improperly recognized these contracts, thereby inflating its revenue and defrauding investors. The SEC’s complaint, which was filed in a federal district court in Minnesota, alleged violations of Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Sections 10(b), 13(a), and 13(b) of the Exchange Act. The SEC sought permanent injunctions, disgorgement with prejudgment interest, a civil penalty, and a permanent officer-and-director bar against the executives.

- The SEC also filed charges against the former CFO and two other former executives of a publicly traded transportation company. The SEC’s complaint alleged that, over the course of about four years, the executives used a wide variety of deceptive accounting maneuvers to manipulate the company’s net earnings. For example, the executives hid incurred expenses by improperly deferring and spreading them across multiple quarters. They also misled the company’s outside auditor about these misstated accounts, causing the company to misstate its operating income, net income, and earnings per share in its annual, quarterly, and current reports filed with the SEC. The complaint filed in a federal district court in Wisconsin alleged that the defendants violated the antifraud and record-keeping provisions of the federal securities laws. The SEC sought permanent injunctions, disgorgement with prejudgment interest, civil penalties, and officer-and-director bars against all three defendants. It also sought clawback bonuses and other incentive-related compensation paid to the former CFO while the alleged fraud was taking place.

- The SEC charged a technology company and its former CEO with misleading investors about the company’s ability to supply glass meeting certain technical standards to a manufacturer of cell phones. The technology company was unable to manufacture the quality and quantity of glass necessary to repay the large sum of money advanced by the cell phone manufacturer under their debt agreement. After the cell phone manufacturer withheld its fourth installment payment, the former CEO falsely stated in second quarter 2014 earnings calls that the company expected to hit its performance targets and receive the fourth installment payment by October 2014. The former CEO also provided unsupported sales projections for the technology company’s sales of the glass, causing the company to misstate its second quarter liquidity and non-GAAP earnings-per-share projections. The technology company filed for bankruptcy two months later. Both the technology company and the former CEO consented to the entry of SEC orders finding that they had violated Section 17(a) of the Securities Act and Sections 13(a) and 13(b) of the Exchange Act. The former CEO agreed to pay more than $140,000 in monetary relief, and both defendants agreed to cease and desist from future violations.

Insider Trading

The SEC initiated two high-profile insider trading cases against senior in-house counsel that were sure to pique interest in legal departments. Insider trading will always remain a priority for the SEC, but these cases against senior lawyers highlight that these cases cut across functional group, seniority level, and geography.

- The SEC charged a publicly traded technology company’s former global head of corporate law and corporate security for using confidential information to make three illicit trades. According to the SEC, the defendant traded the company’s securities in advance of three earnings announcements, resulting in a profit of approximately $382,000. Because the defendant’s duties involved responsibility for the company’s insider trading policy— including notifying employees of the policy’s requirements—the SEC viewed the defendant’s alleged conduct as “particularly egregious.” The lawsuit, and parallel criminal charges, remain

- The SEC filed insider trading charges against an entertainment company’s former associate general counsel. The SEC alleges that the defendant used confidential information about the company’s financial performance to make approximately $65,000 in an illicit trade. The defendant settled with the SEC, agreeing to a permanent injunction, with the court to determine appropriate amounts of disgorgement and penalties. The defendant further pleaded guilty to the DOJ’s parallel criminal

Auditor Liability and Independence

The SEC brought a settled action against an international accounting firm, charging the firm with altering past audit work after receiving stolen information about inspections of the firm by PCAOB. According to the SEC’s order, senior personnel received confidential lists of PCAOB inspection targets and orchestrated a program to review and revise certain audit work papers after reports were issued that the firm had experienced a high rate of audit deficiency findings in prior inspections. The SEC’s order also found that many of the firm’s audit professionals had cheated on internal training exams by improperly sharing answers and manipulating test results. The firm agreed to pay a $50 million penalty and to allocate resources towards ethics and integrity internal controls and investigation of wrongdoing.

Auditor independence also continues to be of interest to SEC Enforcement. The SEC recently brought a settled action against an international accounting firm and two of the firm’s executives for independence violations. The firm allegedly violated Rule 2-01(c)(1) of Regulation S-X when certain of its executives held bank accounts with their audited client’s subsidiary with balances that exceeded the relevant depository insurance limits. The SEC determined that the firm “knew but failed to adequately disclose that [an executive] maintained bank account balances with the audit client’s subsidiary bank that compromised his independence.” Additionally, the SEC determined that the firm’s system of quality controls “did not provide reasonable assurances that the firm and its auditors were independent from audit clients.” For example, the SEC cited the firm’s decision to make lump-sum deposits into the firm’s partner’s accounts with the audited client as a deficient practice.

Further, the SEC found that the firm did not adequately supervise or staff its Office of Independence because certain personnel in its Office of Independence were uninformed of key provisions of Regulation S-X relating to insurance deposit limits. The SEC also found that the firm and its executive caused their client to violate its reporting obligations and that all respondents to the action engaged in improper conduct under Rule 102(e) of the SEC’s Rules of Practice. Under the settlement, the firm agreed to pay $2 million in fines and be censured, while the directors agreed to be suspended from appearing and practicing before the SEC as accountants.

ESG and Climate-Related Disclosures

The first half of fiscal 2019 has also been marked by developments in the interplay between securities laws and sustainability through statements by senior SEC officials and a Commissioner and guidance on proxy access relating to climate change.

In a recent speech, William Hinman, director of the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance, noted that “[s]ustainability disclosure continues to be of interest to investors and other market participants, and the very breadth of these issues illustrates the importance of a flexible disclosure regime designed to elicit material, decision-useful information on a company-specific basis.” While “cognizant that imposing specific bright-line requirements can increase the costs associated with being a public company and yet not deliver the relevant and material information that market participants are seeking,” Hinman “encourage[d] companies to consider their disclosure on all emerging issues, including risks that may affect their long-term sustainability.”

Emphasizing climate and weather-related risks, and referencing the SEC’s guidance in a 2010 interpretive release, Hinman noted that “companies with businesses that may be vulnerable to severe weather or climate-related events should consider disclosing material risks of, or consequences from, these events.” He added that when it comes to these disclosures, and disclosures of other emerging or uncertain risks, “[t]o the extent a matter presents a material risk to a company’s business, the company’s disclosure should discuss the nature of the board’s role in overseeing the management of that risk.”

Commissioner Peirce has emphasized the degree to which ESG reporting has entered the public’s social conscience in a series of recent speeches. For example, in a speech delivered June 18, 2019, she noted, “[p]opular discourse has fueled the efforts of ESG instigators, which include developers of ESG scorecards, proxy advisors, investment advisers, shareholder proponents, non-investor activists, and governmental organizations.” However, she also noted “the ESG tent seems to house a shifting set of trendy issues of the day, many of which are not material to investors, even if they are the subject of popular discourse.” The issue of materiality with respect to ESG reporting is one the SEC continues to grapple with, as highlighted by the SEC’s decision not to sign on to the International Organization of Securities Commissions’ directive to issuers to consider the extent to which ESG factors should be included in their reporting.

While the focus of ESG reporting is often environmental and climate-change issues, Commissioner Peirce also recently discussed the significant public interest in gender equality with respect to service on corporate boards. Peirce explained that while attention to this issue is a reason for optimism, she is concerned that (i) “much of the rhetoric on this subject overstates or misstates the research on the subject”; (ii) “calls to dictate or encourage particular board formulations from the government improperly override private sector decisions, and involvement of the federal government represents an improper federalization of corporate governance”; (iii) “external micromanagement of board composition adds yet another cost to the already high cost of being a public company”; and (iv) “absent mandates, corporate boards will not recruit women.”

Despite increased attention to ESG issues, the SEC has emphasized that companies’ business interests need not always give way to shareholders’ sustainability interests. For example, the SEC recently issued a no-action letter allowing an energy company to exclude a proposal calling for the specific adoption and disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions targets “aligned with the greenhouse gas reduction goals established by the Paris Climate Agreement” from its annual shareholder meeting proxy materials. The basis for the SEC’s decision was its concern that “the Proposal would micromanage the Company by seeking to impose specific methods for implementing complex policies in place of the ongoing judgments of management as overseen by its board of directors.” This no-action decision was consistent with the SEC’s noaction letter allowing another energy company to exclude a similarly specific sustainability proposal from its proxy materials. However, the SEC also recently decided that a petroleum company could not exclude a more general climate-change-disclosure proposal from its shareholder proxy materials.

Supreme Court and Circuit Review

The first half of fiscal year 2019 has also seen significant developments in securities law before the U.S. Supreme Court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The following summaries outline key takeaways from two recent and significant cases.

Lorenzo v. SEC

On March 27, 2019, the Supreme Court held that someone who disseminates a false or misleading statement with intent to defraud, even when the statement was made by another person, can be primarily liable under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c)’s fraudulent scheme provisions. Lorenzo, a broker-dealer’s representative, sent two emails to potential investors misrepresenting the valuation of a company. Lorenzo sent these emails at the request of his boss and copied his boss’s exact language into the emails. Under the Supreme Court’s 2011 decision in Janus Capital Group, Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, only the “maker” of a statement can be primarily liable for its falsity under Rule 10b-5(b). Although Lorenzo was not the “maker” of the statement drafted by his boss, the Court held that disseminating statements understood to be false in personal emails to investors could make Lorenzo primarily liable under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c).

This ruling arguably expands the scope of securities-fraud claims that can be brought by the SEC and private plaintiffs. In the future, the Court acknowledged there may be “borderline cases” where it would be appropriate to narrow the reach of the decision, such as in cases where individuals are only “tangentially involved in dissemination.”

The Robare Group Ltd. v. SEC

On April 30, 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit held that an investment adviser and its principals could not have “willfully” omitted a material fact when the conduct at issue was merely negligent. The SEC alleged that the defendants failed to disclose certain conflicts of interest in their Form ADV registration with the SEC. Upon review of the decision of an administrative law judge, the SEC held that: (i) for purposes of Section 206 of the Investment Advisers Act (“IAA”) antifraud rules governing disclosures to clients, defendants were negligent in failing to disclose conflicts of interests, but did not commit intentional fraud; and (ii) for purposes of disclosure under Section 207 of the IAA, the same conduct constituted a “willful” violation—interpreting “willfulness” to mean intentionally committing an act, regardless of whether one was aware they were violating the law. The D.C. Circuit reversed the SEC’s holding, finding that the language of “willfulness” in Section 207 means that one must intend to omit material information in Form ADV to commit intentional fraud.

The court’s finding is significant because statutes allowing the SEC to sanction regulated entities or associated persons generally require “willfulness,” and the SEC has historically sought sanctions in matters based on merely negligent conduct. It remains to be seen whether this ruling will be limited to the language in Section 207 of the IAA, or whether it will be applied to other securities-law provisions requiring “willful” conduct.

Other Developments of Note

New (Old) Policy on Commission’s Consideration of Settlement Offers with Waiver Requests

On July 3, 2019, Chairman Clayton issued a statement discussing his views on the Commission’s approach to settlement offers that are accompanied by contemporaneous requests for Commission waivers from automatic statutory disqualifications and other collateral consequences. The issue can arise when negotiating a settlement that would, absent further action, trigger an automatic statutory disqualification. Historically, the normal course had been to request a waiver from that disqualification. The authority to decide waivers had been delegated to the policy divisions. Under the last Commission, as part of an overall more aggressive “enforcement” program, that delegated authority had been revoked, which effectively required a settling party to make an unconditional offer of settlement without the guarantee that the Commission would grant a waiver from disqualification. This created challenging settlement considerations and increased the collateral risk of settling, to put it mildly. Under Chairman Clayton’s policy, a settling entity will not face such a choice:

I believe it is appropriate to make it clear that a settling entity can request that the Commission consider an offer of settlement that simultaneously addresses both the underlying enforcement action and any related collateral disqualifications. To be more specific and to discuss the issue in context, an offer of settlement that includes a simultaneous waiver request negotiated with all relevant divisions (e.g., Enforcement, Corporation Finance, Investment Management) will be presented to, and considered by, the Commission as a single recommendation from the staff. This approach will honor substance over form and enable the Commission to consider the proposed settlement and waiver request contemporaneously, along with the relevant facts and conduct, and the analysis and advice of the relevant Commission divisions to assess whether the proposed resolution of the matter in its entirety best serves investors and the Commission’s mission more generally.

* * *

I generally expect that, in a matter where a simultaneous settlement offer and waiver request are made and the settlement offer is accepted but the waiver request is not approved in whole or in part, the prospective defendant would need to promptly notify the staff (typically within a matter of five business days) of its agreement to move forward with that portion of the settlement offer that the Commission accepted. In the event a prospective defendant does not promptly notify the staff that it agrees to move forward with that portion of the settlement offer that was accepted (or the defendant otherwise withdraws its offer of settlement), the negotiated settlement terms that would have resolved the underlying enforcement action may no longer be available and a litigated proceeding may follow.

EDGAR Hacking Case

The SEC brought charges against nine defendants for participating in a scheme to hack into the SEC’s Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval System (“EDGAR”) and use nonpublic information for illegal trading. The SEC alleges that one of the defendants, a Ukrainian hacker, unlawfully gained access to EDGAR in 2016 and extracted test files containing nonpublic earning results. The Ukrainian hacker then allegedly passed the files to eight traders who used the information to trade before the information was publicly released, generating more than $4 million in illegal profits. The SEC seeks a judgment ordering the defendants to pay penalties and return their illegal profits with prejudgment interest, and enjoining them from committing future SEC violations. Notably, seven of the nine defendants were previously charged by the SEC for hacking nonpublic information from draft press releases held in the SEC’s newswire services in two prior cases that remain pending.

Proposed Improvements to M&A Disclosures

On May 3, 2019, the SEC voted to propose amendments to Rules 3-05, 3-14, and Article 11 of Regulation S-X. These proposed amendments are “intended to facilitate more timely access to capital and to reduce complexity and compliance costs of these financial disclosures.”

At present, Rule 3-05 of Regulation S-X typically requires registrants, including investment companies and business development companies, to produce separate annual and unaudited interim pre-acquisition financial statements. Rule 3-14 of Regulation S-X makes it necessary for a registrant that has purchased a significant real estate operation to file financial statements that pertain to that operation. Article 11 of Regulation S-X requires registrants to file unaudited pro forma financial information in regard to an acquisition or disposition.

According to the SEC, the proposed rule amendments will have, among others, the following impacts: (i) updating significance tests under these rules; (ii) requiring the financial statements of acquired businesses to cover up to the two most recent fiscal years, as opposed to the three most recent years; (iii) permitting disclosure of financial statements that omit certain expenses for certain acquisitions of a component of an entity; (iv) clarifying when financial statements and pro forma financial information are required; and (v) no longer requiring separate acquired business financial statements once the business is included in financial statements after the acquisition for more than one year.

In addition, the proposal includes the introduction of new Rule 6-11 and amendments to Form N-14, which pertain to financial reporting of acquisitions involving investment companies. The proposed amendments and additions are subject to a 60-day public comment period.

Emphasis on Small Businesses

In an effort to promote the success of small business, Congress created the SEC’s Office of the Advocate for Small Business Capital Formation (“OASB”) in January 2019. OASB is responsible for supporting the spectrum of small businesses ranging from emerging, privately held companies to publicly traded companies with less than $250 million in public market capitalization. OASB “bolsters the [capital formation prong] of [the SEC’s tripartite mission] by advocating for solutions that facilitate better capital formation for small businesses and their investors.”

In a recent speech at the SEC Speaks conference, Martha Miller, the newly appointed Small Business Advocate, explained that OASB acts as “an amplifier for the regulatory issues [small businesses] face to be better heard in DC,” and that OASB is “fostering accessibility by engaging with the small business community across a variety of channels, geographic regions, and marketplace participants.”

Specifically, Miller noted that Congress tasked OASB with a number of objectives, including: (i) assistance with the resolution of problems with the SEC and self-regulatory organizations (“SRO”); (ii) identification of areas in which small businesses and their investors would benefit from changes in SEC regulations or SRO rules; (iii) identification of problems that small businesses have securing access to capital; (iv) analysis of the potential impact on small businesses and their investors of proposed SEC regulations and SRO rules; (v) outreach to small businesses and their investors; (vi) proposal of regulatory and legislative changes to mitigate the difficulties small businesses face with respect to capital formation and to promote the interests of small businesses and their investors; and (vii) identification of challenges faced by minority-owned small businesses, women-owned small businesses, and small businesses affected by natural disasters.

The SEC also took steps to reduce audit costs for small U.S. listed companies. On May 9, 2019, the SEC announced proposed amendments to the definitions of “accelerated filer” and “large accelerated filer” under Exchange Act Rule 12b-2. The proposed amendments would: (i) exclude reporting companies with less than $100 million in revenues from the requirement that such companies obtain an independent attestation of their ICFR; (ii) increase the transition thresholds for accelerated and large accelerated filers becoming a non-accelerated filer from $50 million to $60 million and for exiting large accelerated filer status from $500 million to $560 million; and

(iii) add a revenue test to the transition thresholds for exiting both accelerated and large accelerated filer status. With respect to these proposed amendments to Rule 12b-2, SEC Chairman Clayton explained that “[t]he proposed rules build on the JOBS Act of 2012 and are aimed at a subset of smaller companies where the additional requirement of an ICFR auditor attestation may not be an efficient way of benefiting and protecting investors.”

The complete publication, including footnotes, is available here.

Print

Print