Meghan McGovern is a Business Analyst, Tracy Branding and Lois D’Costa are Directors, and James Bamford is a Managing Director at Water Street Partners LLC. This post is based on their Water Street memorandum.

MANY JOINT VENTURE BOARD DIRECTORS find themselves in a perceived state of conflicted interest: deference to their nominating shareholder versus loyalty to the joint venture company. The dilemma is a difficult one, as directors often receive conflicting guidance as to whether they should vote based on what is best for the venture in their own independent, professional judgment, which may limit their nominating shareholder’s interests outside the venture, versus simply voting what is in their shareholder’s interests, which may undercut venture performance and expose them to legal liabilities.

Directors on joint venture boards likely owe certain fiduciary duties to the company, most notably a duty of care and duty of loyalty. The duty of loyalty is especially tricky in joint ventures, as board directors who are employees of one shareholder are simultaneously a fiduciary to their employer and to all other shareholders. This issue of mutual agency introduces three types of conflicts: business opportunity conflicts (i.e., situations where a director needs to decide whether a new opportunity is best pursued through the venture or by their shareholder outside the venture); self-dealing conflicts (i.e., situations where the director needs to vote on whether the venture will buy, sell, or otherwise transact with their shareholder for products, services, technology, or other assistance, and the terms associated with such arrangements); and information disclosure conflicts (i.e., situations where a director must decide what potentially-valuable information can and cannot be shared between the venture and their shareholder).

Balancing such conflicts is a regular occurrence on joint venture boards. For instance, the board directors of an Asian media joint venture was asked to grant permission to negotiate a minority investment in a technology company which, unbeknownst to management and other directors, was being separately evaluated by one shareholder. In another instance, the board of a joint venture was asked to approve an investment in an adjacent highly-attractive market, but the directors from one owner as non-core to their own business, which needed the capital to grow elsewhere.

While the law does not treat joint ventures differently from entities with other ownership structures, the notion that a director’s loyalty is “undivided and supreme” [1] as the courts have held in other ownership structures, does not reflect the reality on the ground with joint ventures. After all, joint venture shareholders likely have direct board representation and the opportunity to negotiate specific contractual rights to protect their interests. This creates at least an implied understanding that directors will advance their own shareholder’s interests over those of other shareholders whose directors also serve on the board. Indeed, when freed to do so, such as in Delaware LLCs, co-venturers will often “contract out” of the duty of loyalty, sidestepping default rules which establish such duty. In our experience, joint venture counterparties rarely undertake—and courts are generally not sympathetic to—direct legal action against one partner or its directors for a breach of the fiduciary duty of loyalty [2].

Nonetheless, directors serving on joint venture boards could be exposed to liabilities—and are often gravely warned by legal counsel about such exposures. In the very least, most JV Directors are understandably confused.

Four Contractual Approaches

Today, companies routinely enter into joint ventures to access capabilities and markets, gain scale, and share costs and risks. Many companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, Samsung, Dow Chemical, Siemens, General Motors, Softbank, Starbucks, and Wal-Mart hold interests in a dozen or more joint ventures and depend on these structures for a material share of their overall revenues or income.

To better understand how board directors should approach duty of loyalty in joint ventures, we conducted an analysis of 50 equity joint venture legal agreements [3]—drawn from across industries, geographies, and formation years—to see how the contracts address the matter. We found four basic approaches:

1. Explicit Affirmation: Some venture agreements are drafted to explicitly establish a director’s duty of loyalty to the joint venture and, directly or indirectly, not to the shareholder. The JV agreement of a large oil and gas joint venture corporation makes this singular duty of loyalty clear: “The duty of a director is that of a fiduciary and accordingly the directors on the Board must act and vote in the interests of Corporation and not in the interest of the Shareholders.”

2. Implicit Affirmation: Other agreements make no mention of director fiduciary duties. In most situations, silence implicitly means that directors remain subject to fiduciary duties as most jurisdictions impose fiduciary duties on directors by default.

3. Qualified Waiver: Qualified waivers are present when the agreements provide for blended loyalties or subject a director’s duty of loyalty to specified limitations. Three potential types of qualified waivers are loyalty carve-outs, dual loyalties, and legal waiver with policy caveat. In loyalty carve-outs, the agreements stipulate that for certain matters a director may solely reflect the interests of his or her nominating shareholder, while in other matters the director must vote based on the venture’s interests, even at the expense of the director’s nominating shareholder. Under the dual loyalties structure, the agreements affirm a director’s loyalty to both the venture and the nominating shareholder. Under the legal waiver with policy caveat, the legal agreements waive the duty of loyalty, thus exculpating directors from legal liability for a breach of the duty of loyalty, while the venture’s governance policies (e.g., governance framework, director role descriptions) state that the directors should balance the interests of the venture and a shareholder, with the intent of promoting a cohesive board culture.

4. Complete Waiver: Full waiver refers to agreements that completely waive all JV director fiduciary duties of loyalty. For example, in one healthcare Delaware LLC, the joint venture agreement provides: “Each Member irrevocably and unconditionally waives, and acknowledges that the other Members irrevocably and unconditionally waive. . . any fiduciary duty that could be deemed to be owed to any Member or to the Company by it, any Member or any director” [4]. The effectiveness of this drafting approach ultimately depends on whether the applicable jurisdiction permits parties to waive such duties.

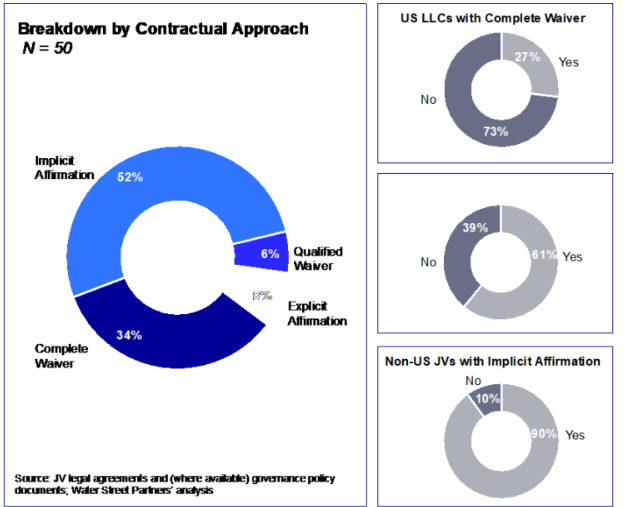

Our analysis found that Implicit Affirmation is the most common (52% of agreements analyzed) and Complete Waiver is second most common (34% of agreements) approach to defining director duties of loyalty (Exhibit 1). Notably, some two-thirds of JVs structured as LLCs include a Complete Waiver. This suggests that limited liability companies may provide greater flexibility and potential protections for parties concerned about liabilities arising from director conflicts of interest. Outside of LLCs, 81% of ventures structured as corporations and 86% of those with other corporate forms remain silent (i.e., Implicit Affirmation) on this matter.

Beyond corporate form, jurisdiction appears to play a role in what approach parties take to fiduciary duties. Some 57% of all U.S. JVs surveyed included a Complete Waiver, while no JVs outside the U.S. included such a waiver. Thus it appears that U.S. companies are much more likely to waive fiduciary duties.

Exhibit 1: Legal Agreement Analysis—Key Data

Practical Guidance

In our experience, joint venture partners should take three steps to address the conflicts JV directors face regarding the duty of loyalty:

Step 1: Structurally Reduce Director Conflicts of Interest

Those negotiating and structuring joint venture agreements should consider various methods to reduce “the zone of conflict” between the partners and within the JV board, including:

1. Non-Compete Provisions.

Covenants to not compete delineate the authorized scope of the venture from that of the shareholder companies, thereby reducing the potential zone of conflict and relieving pressure on directors to balance dual loyalties. For instance, conflicts are less likely if the JV is the exclusive vehicle for a shareholder to compete in the venture’s particular product, customer, or geographic scope, and when the venture is contractually restricted from operating in areas where the shareholder currently operates or has the potential to operate. [5]

2. Reserved Shareholder Matters.

Certain foundational decisions related to the shareholders or the JV are reserved for the shareholders of the JV to decide as opposed to the board, such as amending the JV agreement, selling the company, or bringing in new owners. Unlike directors on a board, shareholders do not have fiduciary duties. Thus expanding the list of reserved shareholder matters to include approvals of more business matters (e.g., dividend policies, five-year business plan, affiliated party transactions) [6] can take potentially conflict-ridden decisions outside the board, reducing any potential duties of loyalty to the venture. [7]

3. Independent Directors.

Roughly 22% of joint ventures have at least one independent director—i.e., individuals who are not employees of any shareholder [8]. The presence of independents can implicitly or explicitly reduce conflicts by allowing these non-partisan directors to drive the discussion (and, in some cases, the voting) on decisions where a shareholder has a conflicted position.

4. Non-Board Decision Forums.

The governance system of joint ventures can be structured to include non-board governance forums to handle certain shareholder or high-conflict decisions. Various JVs establish a Shareholders Committee, often composed of the senior business sponsors from the owners (who may or may not be board directors), to decide major decisions pertaining to strategy and investments. [9] Alternatively, the governance system might include a Commercial Committee composed of non-board directors to handle terms related to supply and purchase agreements with the shareholders.

5. Existence of Shareholder Representatives at Board Meetings.

Shareholder representatives can reduce board conflicts by solely representing shareholder interests. Specifically, shareholder representatives serve as outside observers specifically designated to voice shareholder interests, therefore alleviating pressure on board directors to represent both shareholder and the JV interests.

6. Delegations to Management.

Shareholders and the board can reduce board conflicts by putting more decision power in the hands of the JV CEO and management team. Practically, this is likely to mean increasing overall fiscal sign-off authority and/or allowing management to enter into affiliated party contracts up to a certain financial threshold. [10]

Even if dealmakers use one or more of these methods, in almost all cases, there will still be some potential conflicts with which a director will be confronted. Furthermore, parties may determine that some or all of these methods are not appropriate given the venture’s specific purposes or circumstances. Therefore, dealmakers must then determine how fiduciary duties should apply to directors who may be conflicted—albeit with a reduced number of conflicts.

Step 2: Determine which Contractual Approach to Apply to Director Duties

Next, joint venture partners should determine which contractual approach to codify in the JV agreement regarding the duty of loyalty—Explicit Affirmation, Qualified Waiver, or Complete Waiver. Implicit Affirmation is not recommended as an approach as it leaves directors without guidance about how to behave if they do not know the default law in the applicable jurisdiction.

A suggested way to determine the preferred approach is to work through four questions:

1. Does the jurisdiction impose a fiduciary duty of loyalty on the directors of the JV in its likely corporate form? Whether or not fiduciary duties apply to a specific joint venture will depend upon the JV’s jurisdiction of organization and type of entity (e.g. corporation, LLC etc.). Most jurisdictions impose fiduciary duties on directors. For example, all U.S. states impose such duties on the directors of corporations. Whether a jurisdiction imposes such duties may depend on what type of entity is involved, such as whether the entity is a corporation, LLC or partnership.

2. Can the parties contract out of these default fiduciary duties? Although most jurisdictions impose fiduciary duties, jurisdictions vary in the extent to which parties can contract out of these duties. Some jurisdictions, such as Arkansas, historically have not allowed parties to opt out of fiduciary duties. On the other hand, Delaware allows parties to waive specified fiduciary duties, specifically the duty of loyalty with respect to corporate opportunities. Whether or not parties can waive fiduciary duties may vary by the JV’s jurisdiction of organization and the JV’s corporate form.

3. Is one company more or less likely to be conflicted than its partners in the JV? The shareholders of a joint venture often have asymmetric potential for their directors to have conflicts of interest, typically when one shareholder has a higher degree of interdependence with the venture than the other. A shareholders’ level of interaction with the JV—and thus potential likelihood for director conflicts of interest—stems from a multitude of factors, such as the extent to which the parent company provides services to the JV, the JV’s role in the parent’s supply chain, the amount of shared assets and infrastructure, the prevalence of secondees and synergies in the JV, and the shareholder’s level of ownership and control.

The asymmetric potential for director conflicts is important in determining whether or not to waive the duty of loyalty. A shareholder with a higher degree of interdependence with the JV whose director is likely to be more conflicted would typically want that director to be able to vote however is best for the shareholder, not the JV, and thus should consider a Complete Waiver. By contrast, the less interdependent shareholder whose director is likely to be less-conflicted should consider the opposite—Explicit Affirmation—to emphasize the counter party’s obligation to venture.

4. Do other factors, including growth, funding, and risk considerations favor a particular approach? If the shareholders are equally interdependent, a shareholder should look to other factors to determine whether to waive or affirm duties fiduciary duties. Some of these factors relate to JV growth and funding considerations such as the JV’s potential to IPO, the need for third-party financial investors, and the JV threat to entrenched internal shareholder interests. If such potential, need, or threat is high, shareholders should consider affirming the duty of loyalty. Other factors relate to risk considerations, such as the natural likelihood of conflicts at the board level, the materiality of such conflicts, and the potential legal risk to directors. If these scenarios are likely, material, or of high impact, the JV partner should consider waiving the duty of loyalty. A final factor to consider is the impact that waiving the duty would have on board culture. If the waiver would undercut a cohesive board culture, parties may opt to affirm the duty of loyalty.

Parties should review all of these factors. However, the relative weight of each factor should be determined based on the judgment of the applicable shareholder, with guidance from counsel.

Step 3: Establish Practices to Support Understanding and Implementation

Once shareholders have narrowed the scope of director conflicts and determined a contractual approach to the duty of loyalty, shareholders should establish practices to support director understanding of their rights and obligations in order to facilitate implementation of the selected approach. [11] Some practices to develop this understanding are:

1. Director Training and Development. Director training and development educates directors about whether or not they have fiduciary duties and any limitations on these duties. Directors should receive such training when onboarding onto a JV board and periodically thereafter. Engaging in this training with the board as a group as opposed to individually can help to drive a common understanding and develop board culture.

2. Conflict of Interest Protocols. A second practice to drive understanding is the development of Conflict of Interest Protocols. Conflict of Interest Protocols establish procedures to follow in the event of a conflict of interest. Such Protocols are intended to enable individuals to recognize situations that may involve a conflict of interest and to provide guidance on how to resolve the situation.[12]

3. Director Indemnification. Shareholders may also wish to indemnify JV directors for breach of fiduciary duties in the JV agreement. Such indemnification entitles the director to be reimbursed by the JV for attorneys’ losses incurred as a result of the director’s service to the JV, subject to limitations such as if the director acted in bad faith. Many JVs or their shareholders purchase director and officer insurance to insure against this potential loss. Such indemnification lessens the personal risks to directors as only egregious breaches of their duties will result in personal financial liability.

Although joint venture directors will always be in a game of tug-of-war with the shareholder and joint venture’s interests, the tension on the rope can be eased. Structurally reducing the number of conflicts, incorporating appropriate fiduciary duty contractual language and introducing proactive company practices all serve as viable means to reduce the zone of conflict and give directors tools to appropriately address conflicts that arise. In short, these tactics can turn a weighty tug-of-war battle into a manageable game.

Endnotes

1See Meinhard v Salmon, 164 N.E. 548 (NY, 1928). (go back)

2When suits have been brought citing a breach of a joint venture director’s duty of loyalty, as was the case of TNK-BP, Danone-Wahaha, Pacific National, and other instances, such challenges have been part of much broader partner disputes. Relatedly, there are a number of instances, including the Tiffany’s-Swatch joint venture and Unisuper-News Corp, where partners were sued for breach of the venture agreements including failure to make agreement contributions and fulfill fiduciary duties to the venture and the partners. For additional examples and information, please see: Lois D’Costa and James Bamford, “JV Directors and Conflicts of Interest”, The Joint Venture Exchange, August 2009; James Bamford and Lois D’Costa, “Soothing Directors’ Tortured Souls”. The Joint Venture Exchange, March 2013; and Reginald Goeke, “Three Areas of Litigation Risk in Joint Ventures,” Corporate Counsel, October 31, 2014. (go back)

3This analysis excludes unincorporated and other contractual joint ventures where no separate corporate entity was established. The primary legal document governing the relationship among shareholders of the applicable JV was reviewed for this analysis. Where available, related organizational or governance documents were additionally reviewed. However, shareholders may have addressed the duty of loyalty in other documents not reviewed such as board resolutions, governance policies or other governing documents, which provisions would not be addressed in this analysis(go back)

5For a discussion on covenants to not compete in JVs, please see Sarath Sanga, “A Theory of Corporate Joint Ventures”, California Law Review, October 2018.(go back)

6An extreme example of this approach is the creation of a purely owner-managed entity, where all voting is done by the owners directly, with no formal decision authority delegated to a board, committee, or officers of the venture. To the extent that a board or committees are created, they are solely for purposes other than decision making, including the exchange of information and monitoring management or the operator.(go back)

7Such steps should be taken with caution, as doing so carries negative consequences, including creating a two-tiered governance structure and disempowering the board.(go back)

8Based on Water Street Partners’ proprietary database of joint ventures.(go back)

9An Annual General Meeting is conceptually similar to a Shareholders Committee although, as a practical matter, tends to be more procedural and less substantive in nature.(go back)

10Another means by which decisions are made by JV management as opposed to the JV board is if earnings are retained in the JV as opposed to distributed because JV management then has the discretion to determine how to reinvest the funds, subject to required board and shareholder approvals. This approach also reduces the number of capital calls that need to be approved by the board or shareholders.(go back)

11Partners in existing joint ventures where it is not possible to include an explicit provision in the JV agreement addressing fiduciary duties should still seek to drive understanding among directors of the JV, particularly if such an Implied Affirmation is in the shareholder’s favor.(go back)

Print

Print