Gregory V. Gooding and William D. Regner are Partners, and Jacob Dougherty is an Associate at Debevoise & Plimpton LLP. This post is based on a Debevoise memorandum by Mr. Gooding, Mr. Regner, Mr. Dougherty, Caitlin Gibson, Erik J. Andrén, and Matthew Ryan.

This issue of the Debevoise & Plimpton Special Committee Report surveys corporate transactions announced during the second half of 2023 that used special committees to manage conflicts and reviews key Delaware judicial decisions during that same period ruling on issues relating to the use of special committees. We also discuss certain risk/reward trade-offs to controllers using the MFW playbook to obtain business judgment review of take-private transactions in light of market practice since the MFW decision was issued nearly a decade ago.

The MFW Risk/Reward Trade-off

As discussed in prior issues of this Report, a controller seeking to take its controlled company private can obtain the benefit of business judgment rule review—rather than being subject to the far more onerous test of entire fairness—by adopting the procedural protections set forth in the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Kahn v. M&F Worldwide Corp.[1] To obtain business judgment review, MFW requires that the transaction be subject, from the beginning, to both (i) the approval of a properly functioning special committee of independent directors and (ii) the favorable, informed and uncoerced vote of a majority of the outstanding shares held by persons not affiliated with the controller. Despite the significant protections that MFW provides against stockholder challenges, a meaningful number of take-private transactions announced since that decision have implemented only the first requirement of MFW (special committee approval) but not the second (majority-of-the-minority vote).

The primary reason a controller might decide to subject a take-private transaction to special committee approval, but not to a majority-of-the-minority vote requirement, is that the vote requirement increases completion risk. Perhaps a significant portion of the minority shares are held by retail stockholders, whose votes are generally harder, and more expensive, to obtain than votes of institutional stockholders. Perhaps there is an existing large unaffiliated holder that is hostile to the controller, making a successful majority-of-the-minority vote difficult or impossible to obtain. Or perhaps the controller is wary of the possibility that one or more activist stockholders may seek to acquire a blocking position, creating leverage to demand a price increase.

One might posit that the challenges to obtaining a majority-of-the-minority vote increase if the size of the minority is relatively small, making it easier for an activist to build a potentially blocking stake. If so, one would expect to see a negative correlation between compliance with MFW and the controller’s percentage ownership. One might also expect to see a positive correlation between MFW compliance and the absolute size—in terms of market value—of the public float of the target, for the simple reason that it is more expensive to build a potentially blocking stake in a larger target.

To test these hypotheses, we surveyed controller take-privates announced between March 15, 2014—the day after the Delaware Supreme Court’s MFW decision—and December 31, 2023. Our survey was limited to transactions involving U.S. corporate targets (i) with a deal value of at least $100 million, (ii) in which a Schedule 13E-3 was filed, and (iii) where the acquiring party had a pre-transaction ownership of at least 30% of the target shares. We identified a total of 33 transactions meeting these criteria, of which 26 involved targets incorporated in Delaware.[2]

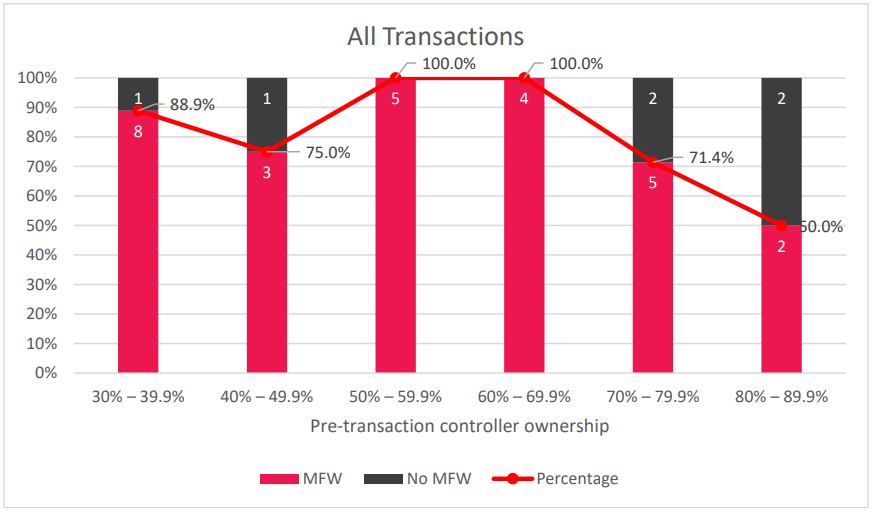

The following chart shows all surveyed transactions and the correlation between compliance with MFW and the size of the controller’s pre-transaction ownership interest, measured in 10% bands from 30% to 90%:

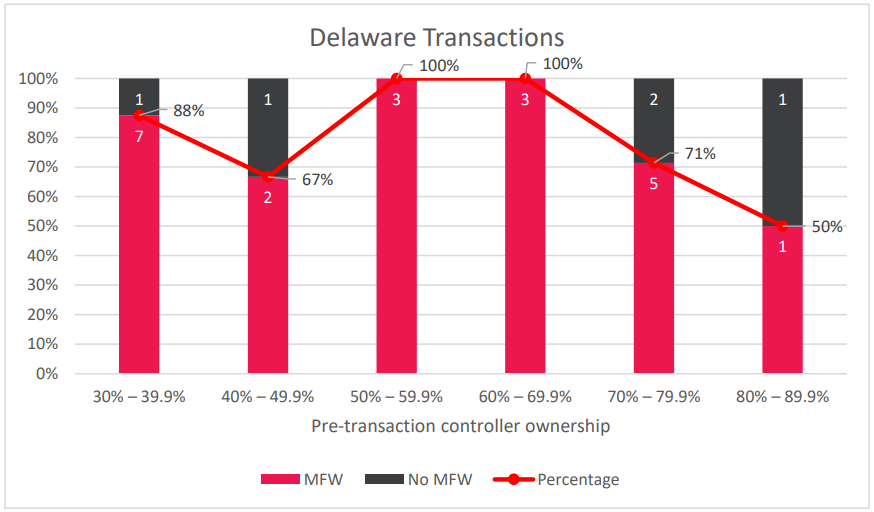

The following chart shows the same data but limited to targets incorporated in Delaware:

Overall, 81.8% of all transactions surveyed (and 80.8% of those involving a Delaware target) were subject to both prongs of MFW: the approval of a special committee of independent directors and the vote of a majority of the unaffiliated shares.[3] As expected, the results showed a meaningful difference in MFW compliance between transactions in which the controller owned less than 70% of the outstanding shares of the target and those in which the controller had a greater interest. Where the controller’s interest was below 70%, the MFW conditions were present in 90.9% of the surveyed transactions (88.2% in the case of Delaware transactions), but where the controller owned more than 70%, both MFW conditions were used in only 63.6% of the surveyed transactions (66.7% of Delaware transactions).

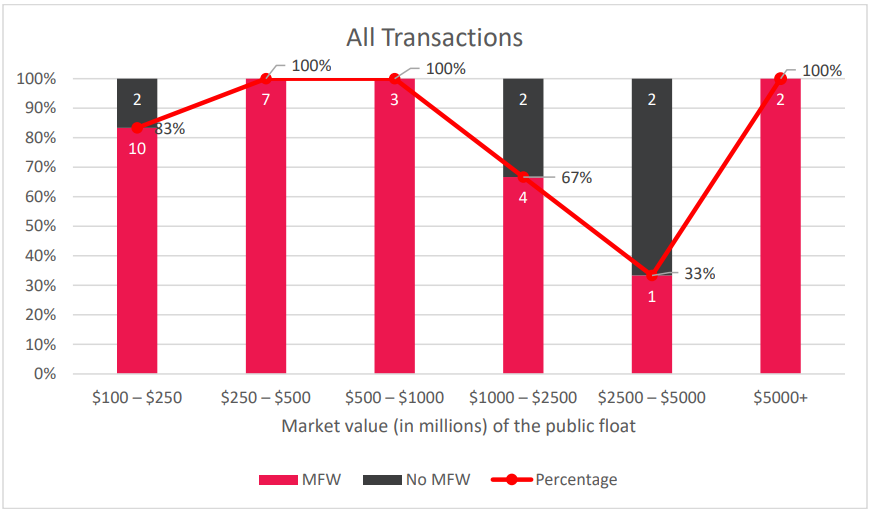

We also looked at the correlation between utilization of MFW and the size of the public float.[4] The following chart shows all surveyed transactions:

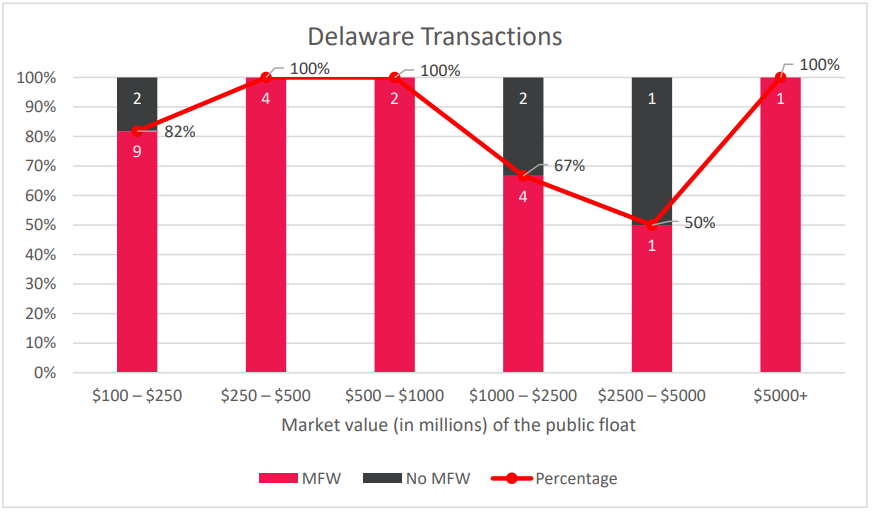

The following chart shows the same data but limited to targets incorporated in Delaware:

While one might have expected that utilization of MFW would be positively correlated with the market value of the public float, that was not borne out in the data. Controller take-private transactions complied with MFW in 90.9% of the surveyed transactions (88.2% in Delaware) in which the value of the public float was less than $1 billion, but in only 63.6% of the cases (66.7% in Delaware) of the surveyed transactions in which the public float had a value of $1 billion or more. This suggests that controllers tend to see greater completion risk arising from a relatively small percentage public float than they do from a relatively small value of public float.

Compliance with MFW’s requirements provides a controller significant benefits against stockholder litigation. However, it also introduces additional completion risk, and potentially greater risk where the minority interest the controller seeks to acquire is relatively small. Relying solely on approval of the transaction by a properly constituted special committee, while not sufficient to avoid entire fairness review, still has significant benefits to the controller: it shifts the burden of proof on the question of entire fairness to the stockholders challenging the transaction and, more importantly, is itself evidence of a fair process. As the data above indicates, for some controllers, the benefit of business judgment rule review may not be deemed worth the additional risk created by a majority-of-the-minority vote.

Compliance with MFW Does Not Result in Deference to Deal Price in a Subsequent Appraisal Action

Former stockholders of Pivotal Software sought appraisal following the acquisition of Pivotal by VMware for $15 per share. Both companies were controlled by Dell Technologies, and Michael Dell sat on the board of both companies. The acquisition of Pivotal by VMware complied with MFW, having been negotiated and approved by a special committee of independent directors of Pivotal and receiving the affirmative vote of a majority of the shares held by Pivotal stockholders not affiliated with Dell. In the appraisal action, Pivotal asserted that as a consequence of the transaction’s compliance with MFW the merger price should act as a cap on the court’s fair value determination. The court rejected this position, finding it inconsistent with prior case law that held that fair price for purposes determining compliance with entire fairness may be less than fair value as determined in an appraisal action. The court stated that “the central justification for basing fair value on deal price under Delaware law is that the process is subject to competitive market forces” and that “no appraisal decision of a Delaware court has given weight to deal price when determining fair value in the context of a controller squeeze-out.” The court also pointed to the Court of Chancery’s original MFW holding, which “identified appraisal as a safety valve to protect minority stockholders from any mischief that might result from applying the business judgment rule to controller squeeze-outs.” Despite rejecting the proposition that the $15 deal price acted as a cap, the court ultimately found—after utilizing traditional appraisal valuation methodologies, including discounted cash flow and comparable companies analyses—that the fair value of Pivotal was $14.83 per share. HBK Master Fund, LP, et al. v. Pivotal Software, Inc., C.A. No. 2020-0165-KSJM, memo. op. at 41- 43 (Del. Ch. Aug. 14, 2023).

Recommendation by Special Committee Did Not Relieve Full Board from Duty to Exercise Due Care in Approving Conflicted Transaction; Failure of Board to “Dig in” Potentially Evidenced Bad Faith as Well as Breach of Duty of Care

The Delaware Court of Chancery denied a motion to dismiss breach of fiduciary duty claims against the directors of GoDaddy, Inc. in connection with their approval of an $850 million “buyout” of a tax receivable liability to certain related parties, which liability was carried on the company’s audited financial statements at $175 million. A special committee had been formed and given the full authority of the board to approve or reject the transaction. The committed hired legal and financial advisors and held at least six meetings. The financial advisor prepared and presented to the committee a valuation report. Ultimately, however, the committee did not exercise its authority to approve the transaction on behalf of the company but rather “lateraled” the decision back to the full board, together with the committee’s recommendation that the board grant such approval.

The court found that plaintiffs adequately alleged that the board failed to “dig in” on the proposed transaction, and instead approved the transaction in a 30-minute meeting, without having received a fairness opinion, without the firm that performed the financial analysis of the buyout being present, and despite its awareness of the discrepancy between the valuation of the liability on the company’s financial statements and the price to be paid to its affiliates to settle the liability. Although the committee recommended that the board approve the transaction, the committee did not review its analysis with the board or otherwise provide information that would help it do an independent analysis. The court found that the cursory nature of the board’s decision to approve the buyout evidenced not only the potential failure of the directors to meet their duty of care but, given the various conflicts that existed at the board level, contributed to an inference of bad faith. IBEW Local Union 481 Defined Contribution Plan & Trust v. Raymond E. Winborne, et al. and GoDaddy, Inc., C.A. No. 2022-0497-JTL, opinion (Del. Ch. Aug. 24, 2023).

Transaction Subject to Entire Fairness Review Held to Be Procedurally Unfair as a Result of “Bullying” Behavior, but Controller Subject to Only Nominal Damages Because Price Was Fair

In 2023, IDT Corporation, controlled by Howard Jonas, spun off its wholly owned subsidiary Straight Path Communications, Inc., following which Jonas controlled both companies. IDT agreed to indemnify Straight Path for losses resulting from actions taken prior to the spin-off. Subsequently, the FCC brought regulatory claims against Straight Path in respect of pre-spin actions taken by IDT, which claims were settled pursuant to an agreement that required Straight Path to be sold and 20% of the purchase price to be paid to the FCC. In connection with the contemplated sale, Straight Path initially contemplated setting up a litigation trust to pursue indemnification claims against IDT on behalf of its stockholders. However, Jonas objected to that proposal and the parties ended up agreeing instead to a settlement in which Straight Path released its indemnity claims against IDT in exchange for a payment of $10 million, which release was approved by a special committee of independent directors of Straight Path.

Straight Path was ultimately sold to Verizon for $3.1 billion. After the sale, former Straight Path stockholders brought breach of fiduciary duty claims against Jonas, asserting that the terms of the release of IDT were unfair to Straight Path and its minority stockholders. The Delaware Court of Chancery found that Straight Path’s release of the indemnity claim against IDT was subject to entire fairness review, given that Jonas effectively stood on both sides of the transaction. Notwithstanding the board’s use of a special committee, the court found that the Straight Path process was unfair to the minority stockholders on the ground that Jonas “bullied” the special committee members into submission. However, despite the lack of procedural fairness, the court found the price paid to IDT for the release to be fair. The court held that Straight Path’s claim against IDT in fact had no value because Straight Path had failed timely to provide IDT with proper notice of its intention to seek indemnification. While IDT had constructive knowledge of the FCC settlement and that it was exposed to an indemnity claim by Straight Path as a result of that settlement, its knowledge did not result from having received a notice that complied with the terms of the indemnification agreement. Because the price was found to be fair, the court held Jonas liable for only nominal damages. In re Straight Path Communications, Inc. Consolidated Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 2017-0486-SG (consol.), memo. op. (Del. Ch. Oct. 3, 2023).

Endnotes

188 A. 3d 365 (Del. 2014).(go back)

2The non-Delaware transactions included in the survey involved target companies incorporated in jurisdictions where the corporate law relating to controller and director liability appears largely similar to Delaware. However, we excluded from the survey two transactions involving target companies incorporated in Nevada given that the underlying corporate law is sufficiently different from Delaware’s to make compliance with the MFW procedures less relevant to a fiduciary duty claim. Those transactions involved a 41% controller and an 83% controller, respectively, and were both subject to approval by a special committee but not to a majority-of-the-minority vote.(go back)

3MFW compliance for purposes of this survey was not adjusted to account for transactions in which the MFW protections were nominally present but where their implementation was subsequently found by a court to be flawed (e.g., because of issues as to committee independence or proper functioning, or whether the conditions were present ab initio).(go back)

4Public float is determined on the basis of the deal price and the total number of the shares not held by the controller.(go back)

Print

Print