The following post comes to us from Jonathan C. Dickey, partner and Co-Chair of the National Securities Litigation Practice Group at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, and is based on portions of a Gibson Dunn publication. The complete publication is available here.

2013 proved to be a watershed year for securities litigation, and 2014 is shaping up to be a “career killing” year for plaintiffs’ lawyers specializing in 10b-5 class actions. In what may turn out to be one of the most important cases in the last three decades, the Supreme Court will address the long debated fraud-on-the-market theory in Halliburton II, and address head on whether the Court’s decades-old ruling in Basic v. Levinson establishing that theory should be overruled. The case for overruling Basic is a strong one, with at least four justices having expressed serious concerns about the fraud-on-the-market theory in the Court’s 2013 decision in Amgen. See “A Shot Across the Basic Bow,” in our 2013 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update. If, as many court observers predict, the Court in fact overturns the fraud-on-the-market theory, securities class actions as we know them may be consigned to the dust heap.

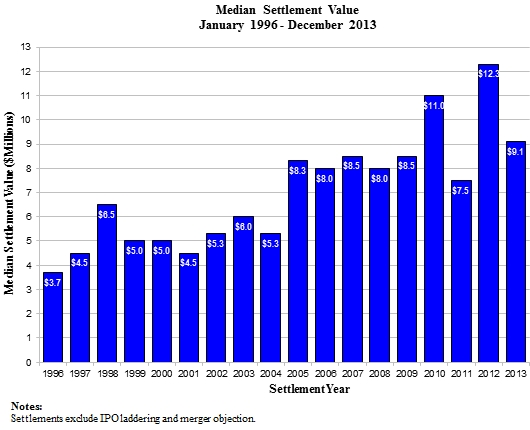

In the meantime, filing and settlement trends indicate a return to pre-credit crisis norms, with median settlement values generally declining to levels much lower than the eye-popping amounts seen in the last two years. Nevertheless, the number of new class actions filed in 2013 is consistent with the “steady state” of over 200 cases per year over the last several years, with the technology sector continuing to be one of the leading industry sectors for new class actions, and M&A litigation in particular being a significant focus of these cases.

We highlight these and other notable developments in shareholder litigation in our 2013 Year-End Securities Litigation Update below.

Filing and Settlement Trends

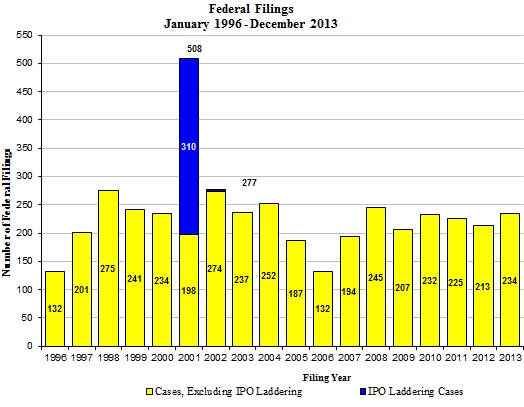

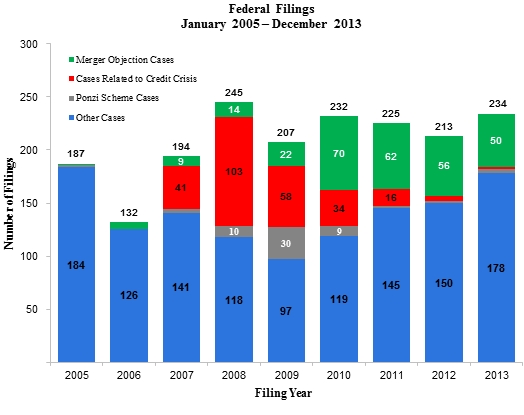

Filing and settlement trends continue to reflect a “steady state” of several hundred cases a year, notwithstanding the steep decline in credit crisis cases in 2013 from their all-time high of over 100 class actions in 2008. According to a recent study by NERA Economic Consulting (“NERA”), the roughly 234 new class actions filed in 2013 are slightly higher than the five-year average of 222 cases, but the mix of those cases has changed. Merger-related cases have held steady in 2013 with the five-year average of 52 cases per year. “Other” cases—the kinds of cases that have historically been brought—have spiked significantly over the last five years, from a low of 97 in 2009 to 178 cases in 2012. These types of cases hit a nine-year low in 2009, perhaps due to the scores of credit crisis cases—but now have returned to their pre-credit crisis levels (187 cases in 2005, and 178 cases in 2013).

In 2013, the number of settlements was flat compared to 2012—96 settlements in 2013 compared to 94 in 2012. But the number of settlements in the last two years represents a general decline in the number of settlements per year, dating back to the high-water mark of 151 settlements in 2007.

Median settlement amounts in 2013 dropped dramatically in 2013 compared to 2012: while 2012 median settlements stood at $12.3 million, the 2013 median amount was $9.1 million. The 2013 median amount is consistent with the five year average of $9.68 million, so perhaps it signals a “return to normal” after several years of outsized credit crisis settlements.

In stark contrast to median settlement amounts, the average settlement for all settled cases in 2013 was $71 million—over double the average amount in 2012 of $36 million. The 2013 average also is dramatically higher than the five-year average of $40 million.

Finally, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses in the first half of 2013 were 2.0%, up from 1.8% for the full year 2012, but slightly lower than the six-year average of 2.15%.

As discussed in later sections of this Year-End Report, several key cases may significantly alter the securities litigation landscape and may materially impact future levels of new case filings and settlements. The case that could have the greatest dampening effect on new securities class actions will be the Supreme Court’s decision in Halliburton II, in which a ruling is expected by the end of this Term in June 2014. If, as many speculate, the Court overrules the “fraud on the market” theory, shareholder class action litigation may cease to exist as we know it. Plaintiffs’ lawyers might then migrate to state court (as was true after passage of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act in 1995) or begin filing single-plaintiff suits, at least where the dollar losses of large institutional investors or pension funds are sufficiently large to warrant a stand-alone suit. If, alternatively, the Court does not entirely overrule the “fraud on the market” theory, but raises the bar on the proof required to establish that securities trade in an efficient market, that too is likely to lead to fewer cases being filed and/or more cases that do not survive class certification. The stakes are high, and depending on the outcome in Halliburton, an entirely new approach to shareholder litigation may be required.

Class Action Case Filing Trends

Overall filing rates are reflected in Figure 1 below (all charts courtesy of NERA). There were 234 new cases filed in 2013. Notably, this figure does not include the many such class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. These cases, not included in the statistics discussed here, represent a “force multiplier” of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation in the United States today.

Figure 1:

Mix of Cases Filed in 2013

Credit Crisis Cases. There were virtually no new federal court class actions filed against financial institutions in 2013, reflecting the dramatic decline of “credit crisis” class actions since 2008. While a number of major credit crisis cases are still pending, the trend line is expected to continue: like stock option “backdating” cases, credit crisis class actions will soon be consigned to history. That said, while credit crisis class actions are on the wane, a new generation of cases have replaced them: single-plaintiff suits by government agencies (such as the Federal Housing Finance Agency on behalf of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac), monoline insurers (such as MBIA), and institutional and pension fund investors. A few have already resulted in settlements in excess of $100 million.

Merger Cases. Merger-related litigation continues to represent a significant portion of new federal court securities class action filings. NERA reports that in 2013, merger class actions represented roughly 20% of new federal court securities class action filings (50 out of 234 cases). Today, well over 80% of all M&A transactions are challenged by investors, either in federal court class actions, state court class actions, or shareholder derivative actions. This is so even where the proposed transaction provides shareholders of the acquired corporation with substantial premiums. As discussed below in our discussion of “Merger & Acquisition and Proxy Disclosure Litigation Trends,” the exposure of corporations to M&A litigation spans a range of subject matters, with sometimes unpredictable results. Those results may become even less predictable if, as expected, Chancellor Leo Strine is appointed as the new Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, as Chancellor Strine has shown a willingness to “break new ground” in his rulings in cases before him in the Chancery Court.

Figure 2:

Filings By Industry Sector. The trends in new case filings against particular industry sectors reflect the decline in “credit crisis” cases, as new suits against financial institutions have dropped from record-shattering levels in 2009 to third place in 2013 (15% of all new case filings), behind the technology and health sectors (19% and 18%, respectively, of new case filings). The energy sector ranked fourth (11%). The biggest jump in new case filings on a percentage basis compared to 2012 was in the commercial and industrial sector, where new filings grew from 4% in 2012 to 7% in 2013. By contrast, eight out of twelve sectors remained flat to down from the prior year. Sectors that moved up the rankings the most were the retail and transportation sectors. See Figure 3 below.

Figure 3:

Class Action Settlements

As Figure 4 shows, the median settlement amount of $9.1 million in 2013—generally a better barometer of settlement trends—was hugely down in 2013 compared to 2012’s median amount of $12.3 million. Still, the Q1 2013 figure is higher than seven of the last ten years—not an occasion to claim victory.

Figure 4:

One can speculate about what may account for the up-and-down fluctuation in median and average settlements over the last five years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the ’34 Act or Section 11 of the ’33 Act. The last few years also included the settlement of several of the major credit crisis cases totaling several billion dollars. Whatever the variables, median and average settlement amounts over the last decade should not be viewed as a barometer of either a long-term increase or decline in settlement values.

Fraud-On-The-Market under Fire

The Case of the Decade: Certiorari Granted in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc.

As widely predicted and discussed in our 2013 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, the Supreme Court will revisit the viability of the fraud-on-the-market theory presumption of reliance. On November 15, 2013, the Supreme Court granted certiorari to review Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co. (“Halliburton II”), 718 F.3d 423 (5th Cir. 2013) and is now poised to decide the continued viability and scope of the fraud-on-the market theory, as well as the more limited question of whether price impact evidence rebutting the presumption is appropriately introduced and weighed at the class certification stage.

Reliance on a misrepresentation in connection with the purchase or sale of a security is an essential element of a Section 10(b) claim. Plaintiff classes generally satisfied this requirement through a presumption of reliance under the “fraud-on-the-market theory.” The theory, endorsed by the Supreme Court in Basic v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988), allows plaintiffs to forgo the formidable task of proving actual reliance by class members on a specific misrepresentation in purchasing or selling a security. Plaintiffs instead may be presumed to have relied on a misrepresentation “aired to the general public” where the security traded in an efficient market. Amgen Inc. v. Conn. Ret. Plans & Trust Funds, 133 S. Ct. 1184, 1192 (2013) (discussing Basic). The Supreme Court has stated that “[t]his presumption springs from the very concept of market efficiency,” id., and embodies the notion that where a market generally incorporates public information into the security’s price, an investor who purchased stock at a particular price presumptively relied on the alleged public misrepresentation. See Basic, 485 U.S. at 247. Without the fraud-on-the-market presumption, plaintiffs would have a difficult time “meet[ing] the traditional reliance requirement because they [could not] establish that they engaged in a relevant transaction … based on [a] specific misrepresentation.” Amgen, 133 S. Ct. at 1208 (Thomas, J. dissenting) (internal quotation marks omitted).

As noted in our mid-year review, a majority of the Justices in Amgen acknowledged serious misgivings about the fraud-on-the-market theory and signaled an opening to revisit Basic. See Amgen, 133 S. Ct. at 1197 n.6; id at 1204 (Alito, J., concurring); id at 1206 (Scalia, J., dissenting); id. at 1208 n.4 (Thomas, J., dissenting). And while Amgen may have been “a poor vehicle” for doing so, 133 S. Ct. at 1197 n.6 (majority opinion), the Supreme Court found a suitable vehicle in Halliburton II. The Court’s acceptance of the petition for review suggests an openness to substantially modifying or even overruling Basic. If the Court were to abandon or substantially curtail Basic, it would make securities-fraud class actions much more difficult to maintain, as “securities-fraud class actions [are made] possible” because the fraud-on-the-market presumption “convert[s] the inherently individual reliance inquiry into a question common to the class.” Amgen, 133 S. Ct. at 1209 (Thomas, J., dissenting).

Halliburton and Amici’s Opening Salvo: Basic Was Wrongly Decided, and Its Flaws Have Only Become More Clear Over Time

Although the matter has not yet been fully briefed, opening briefs have presented the initial assault on Basic. And the significance of the issue has inspired a flurry of amicus briefs, including from former members of Congress, law professors, and industry groups.

In its opening brief, Halliburton contends that Basic was wrong when decided as a matter of statutory interpretation and economic theory. The Section 10(b) cause of action is a “judicial construct,” and in defining its contours, the Court has previously looked to other causes of action in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Here, the closest textual analogue in the 1934 Act, Section 18(a), expressly requires actual reliance. Br. for Petitioners, No. 13-317, at 12-13; see also Joseph A. Grundfest, Damages and Reliance under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act (Rock Center for Corporate Governance, Working Paper Series No. 150, 2013).

Twelve former legislators, government lawyers, and SEC officials filed an amicus brief (discussed on the Forum here) addressing the respondent’s expected argument, namely, that Congress endorsed fraud-on-the-market when it enacted the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (“PSLRA”) without addressing the standard for proving reliance. In the Amgen decision, Justice Ginsburg made this precise contention, stating that when Congress enacted the PSLRA, it took “steps to curb abusive securities-fraud lawsuits” but “rejected calls to undo the fraud-on-the-market presumption of class-wide reliance endorsed in Basic.” Amgen, 133 S. Ct. at 1201. The former officials’ amicus brief contends that at the time of enacting the PSLRA, Congress was confronted with “competing calls to overturn, modify, or codify the Basic presumption,” and that “Congress simply left the fate of that judicially-created presumption to a future Congress or this Court.” Br. for Former Members of Congress et al. as Amici Curiae in Supp. of Neither Party, No. 13-317, at 2. The former officials urge that the “Court should not take Congress’s silence as implicit acceptance or rejection of Basic’s fraud-on-the-market theory.” Id. at 3.

In its principal brief, Halliburton also noted that the Court’s recent class action and Section 10(b) cases make Basic’s presumption of reliance appear even more anomalous. Br. for Petitioners at 25. The rulings in Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 133 S. Ct. 1426 (2013) and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 131 S. Ct. 2541 (2011), have emphasized that plaintiffs must affirmatively demonstrate compliance with the commonality element of Rule 23 in order to achieve class certification. Halliburton argued that Basic flouts this principle by presuming common reliance in the face of strong evidence to the contrary. Br. for Petitioners at 26.

Appellant’s and amici’s briefs also argue that the reservations of the dissenters in Basic have, over time, proven well founded. As Halliburton pointed out, Justices White and O’Connor argued in dissent in Basic that it was unwise to embrace the nascent economic theory of the “efficient-capital-market hypothesis” when that theory was both unproven and not within the Court’s expertise. Br. for Petitioners at 14 (quoting Basic, 485 U.S. at 253 (White, J., dissenting)). The academic consensus now appears to reject Basic’s view of market efficiency, in part because investor attempts to identify undervalued stocks demonstrate widespread betting that securities markets are inefficient. Markets move irrespective of public information due to several factors, such as the herd mentality of investors, algorithmic trading programs, and response to media attention to information previously made public, among others. Br. for Petitioners at 16-17, 19-21. As argued in an amicus brief submitted by Vivendi S.A., many investors, including sophisticated institutional investors, volatility arbitragers, and “value” investors, “do not rely on the integrity of market price” but instead rely on their own, private valuation of stock. Br. for Vivendi S.A. as Amicus Curiae in Supp. of Petitions, No. 13-317, at 4-7. [1] It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that the theory has led to confusion and inconsistent results. Indeed, the factors repeatedly used by courts in assessing market efficiency and certifying class actions (such as the Cammer factors, see Cammer v. Bloom, 711 F. Supp. 1264 (D.N.J. 1989)) have been shown to be largely incapable of differentiating between efficiently and inefficiently priced stocks. Br. for Petitioners at 23.

In urging the Court to overturn Basic, Halliburton and amici have also highlighted the practical arguments as well. While Basic adopted the presumption of reliance because it was necessary for class actions, the briefs question the implicit premise that such class actions are necessary to vindicate securities fraud, and instead suggest that these class actions have become nothing more than a drain on business. And while the presumption of reliance is said to be rebuttable, in all practical terms it is irrebuttable. As a result, actions are settled as “routine tolls that large companies must pay” and the cost of litigation and potential damages make it economically prudent to settle and abandon meritorious defenses. Br. for Petitioners at 40-41. In its amicus brief, the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation has noted that the aggregate value of securities class action settlements was approximately $68.1 billion from 2000 through 2012, suggesting that insurance costs for Fortune 500 companies are six times higher in the United States than in Europe as a result. See Br. for Comm. on Capital Markets Regulation in Supp. of Petitioners, No. 13-317, at 6-7. Settlement payments and litigation defense costs paid by corporations ultimately fall on shareholders, and settlement payments—amounting to only 1.8% of alleged losses in 2012—are merely transferred from one shareholder to another, subject to a 23-32% cut for plaintiffs’ attorney fees. Br. for Petitioners at 43-44. A typical diversified investor is only on the paying or gaining side by happenstance and a “significant portion of actual settlement amounts is never distributed to class members.” Br. for Comm. on Capital Markets Regulation at 13.

Of course, the Court may stop short of throwing out the fraud-on-the-market theory altogether. The Court might require a more rigorous or nuanced application of the fraud-on-the-market theory. As has been suggested in academia, an alternative to rejecting the theory in its entirety might be requiring proof of “market efficiency” for each of plaintiffs’ theories of liability. For further discussion, see Joseph A. Grundfest, Damages and Reliance under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act (Rock Center for Corporate Governance, Working Paper Series No. 150, 2013) (discussed on the Forum here).

A Narrower Question—Whether Price Impact Evidence Should Be Weighed at the Class Certification Stage.

While many have urged the Court to reconsider whether the presumption of reliance should even exist, the Court could resolve only the narrower question presented: whether price impact evidence rebutting the fraud-on-the-market presumption is appropriately introduced and weighed at the class certification stage.

In the Fifth Circuit, Halliburton attempted to defeat class certification by showing that individual issues would predominate if plaintiffs failed to prove that the alleged misstatements affected price. In upholding class certification and refusing to consider Halliburton’s evidence regarding price impact, the Fifth Circuit reasoned that under no circumstance would individual issues predominate because, if no price impact is proved, any individual claims would necessarily fail for no proof of loss causation. Halliburton II, 718 F.3d at 434. In reaching this conclusion, the Fifth Circuit followed Amgen, where the Supreme Court noted that because “materiality is … an essential predicate of the fraud-on-the-market theory,” 133 S. Ct. at 1195, there was “no risk whatever that a failure of proof on the common question of materiality will result in individual questions predominating,” id. at 1196-97.

In its principal brief to the Supreme Court, Halliburton distinguishes Amgen by contending that, unlike materiality, market efficiency is not an element of a Rule 10b–5 claim. Moreover, Halliburton argues that, if it were to rebut the fraud-on-the-market presumption by demonstrating no price impact post-certification, reliance would turn into an individualized question of fact and could not be resolved on a class-wide basis. Br. for Petitioners at 49-52.

Several amicus briefs focus on this narrower question, urging the Court to permit defendants to rebut the presumption of reliance with price impact evidence at the class certification stage. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, for example, filed an amicus brief highlighting the practical effect of when price-impact evidence is considered. The costs to defendants of allowing class certification and then later examining materiality or loss causation as a merits issue are simply too high, the AICPA argued, because defendants settle even cases that have no merit once a class is certified. Br. for Am. Inst. of Certified Pub. Accountants as Amicus Curiae in Supp. of Petitioners, No. 13-317, at 23-24 (nothing that the small risk of losing securities class actions later on the merits is overshadowed by the potential for class-wide damages). The Washington Legal Foundation likewise urged that allowing defendants to rebut the presumption of reliance at the class certification stage would harmonize the Court’s affirmative misstatement and omission jurisprudence because the Affiliated Ute presumption, applicable in cases alleging omissions, may be rebutted at the class certification stage with evidence that defendant did not have a class-wide duty to disclose. Br. for Wash. Legal Found. as Amicus Curiae in Supp. of Petitioners, No. 13-317, at 13-23 (discussing Affiliated Ute Citizens of Utah v. United States, 406 U.S. 128 (1972).

In sum, regardless of whether the Court decides the ultimate question of the continued viability of fraud-on-the-market theory or settles on the narrower question, the Court is poised to deliver yet another significant decision in the securities context in the coming year.

Fraud-on-the-Market in the Lower Courts

In the last half of 2013, lower courts wrestled with the Supreme Court’s signals regarding the viability of Basic’s fraud-on-the-market presumption.

In IBEW Local 90 Pension Fund v. Deutsche Bank AG, No. 11 Civ. 4209(KBF), 2013 WL 5815472 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 29, 2013), Judge Forrest of the Southern District of New York took a hard look at plaintiffs’ evidence and expert testimony supporting the fraud-on-the-market presumption. The court ultimately found that class action plaintiffs failed to meet their burden of establishing market efficiency for the relevant securities. Citing Amgen, the court explained that “[t]he presumption of reliance is, however, just that—a presumption. It is rebuttable.” Id. at *20.

The court noted that, “[t]o defeat the presumption of reliance, defendants do not, therefore, have to show an inefficient market. Instead, they must demonstrate that plaintiffs’ proffered proof of market efficiency falls short of the mark.” Id. The vast majority of the securities in question were traded outside the United States, primarily in Germany on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange. Id. at *3 n.12. Defendants presented evidence that information tended to be disclosed and incorporated into the securities’ price first in Germany, when the U.S. markets were closed, and that even when both U.S. and German markets were open, the German markets led in incorporating the information. Id. at *9. Plaintiffs’ expert had not analyzed the German market at all, focusing entirely on the U.S. market. Id. at *21. The court concluded that plaintiffs’ expert’s failure to analyze the primary market for the securities was fatal to his analysis. Id. at *21. The court’s denial of class certification provides an example of the searching review in which lower federal courts may increasingly engage post-Amgen.

In another rigorous application of Rule 23, the district court in In re BP P.L.C. Sec. Litig., No. 4:10–md–2185, 2013 WL 6388408, at *1 (S.D. Tex. Dec. 6, 2013), likewise denied a motion for class certification for various reasons. As to the fraud-on-the-market theory, the district court found that the alleged misrepresentations were inadequately publicized to be incorporated into the stock price. In a securities lawsuit arising from the Deepwater Horizon explosion and ensuing oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, plaintiffs alleged that BP had made fraudulent misstatements in regulatory filings that were later brought to light by the spill. Id. In evaluating the evidence on plaintiffs’ motion for class certification, the court cited Amgen and Halliburton I in noting that the “Supreme Court has clarified that a proposed class representative need not establish materiality or loss causation to invoke the [fraud-on-the-market] presumption.” Id. at *13 (citations omitted). Rather, the court explained, “the inquiry at this stage is focused on trade timing, market efficiency, and publicity.” Id. (quotation and citations omitted). Because the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that the particular misrepresentations “were known by the market and incorporated in the [securities’] price prior to the Deepwater Horizon explosion,” the court denied class certification. Id. at *15.

Notwithstanding the pro-defense rulings cited above, most lower courts have continued to apply the Basic fraud-on-the-market presumption without critical examination. See, e.g., Harris v. Amgen, Inc., No. 10-56014, 2013 WL 5737307, at *15 (9th Cir. Oct. 23, 2013) (applying fraud-on-the-market theory to ERISA plan participants in the same manner that would apply to any investor); Smilovits v. First Solar, Inc., No. CV12–00555–PHX–DGC, 2013 WL 5551096 (D. Ariz. Oct. 8, 2013) (certifying securities class action on finding of market efficiency based on evaluation of the Cammer factors, but rejecting plaintiffs’ assertion that the predominance requirement was satisfied because plaintiffs conceded they would never seek to individually assert reliance and would instead rely entirely on the fraud-on-the-market theory); In re Puda Coal Sec. Inc. Litig., No. 11 Civ. 2598(KBF), 2013 WL5493007, at *20 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 1 2013) (citing Basic in certifying a securities class action, but limiting the class to a period when plaintiffs had affirmative evidence of market efficiency because the burden is on plaintiffs to demonstrate an efficient market); Plumbers & Pipefitters, Nat’l Pension Fund v. Burns, No. 3:05CV7393, 2013 WL 4776278 (N.D. Ohio Sept. 4, 2013) (certifying securities class action after evaluating conflicting expert testimony regarding five Cammer factors and concluding that bonds at issue traded on an efficient market); Hawaii Ironworkers Annuity Trust Fund v. Cole, No. 3:10CV371, 2013 WL 4776258 (N.D. Ohio Sept. 4, 2013) (following Amgen in ruling that materiality of alleged misrepresentations did not need to be determined at the class certification stage, but denying class certification because defendants had failed to prove that deception was communicated to the public and accordingly plaintiffs could not rely on the fraud-on-the-market presumption).

If anything, the recent district court opinions perhaps highlight the need for definitive guidance from the Supreme Court on the continuing viability and scope of the fraud-on-the-market theory.

Endnotes:

[1] Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher is counsel for Vivendi S.A.

(go back)

Print

Print