The following post comes to us from Dan Ryan, Leader of the Financial Services Advisory Practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, and is based on a PwC publication.

Ever since the Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research (“OFR”) released its report on Asset Management and Financial Stability in September 2013 (“OFR Report” or “Report”), the industry has vigorously opposed its central conclusion that the activities of the asset management industry as a whole make it systemically important and may pose a risk to US financial stability.

Several members of Congress have also voiced concern with the OFR Report’s findings, particularly during recent Congressional hearings, as have commissioners of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Further complicating matters, a senior official of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) recently expressed alarm about banks working with alternative asset managers or shadow banks on “weak” leveraged lending deals.

Amidst this domestic controversy, the Financial Stability Board (“FSB”) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (“IOSCO”) issued a Consultative Document in January proposing methodologies for identifying globally active systemically important investment funds. [1] Like the OFR Report, the Consultative Document explains why designation may be necessary without addressing which firms may be designated or what additional regulations would apply. However, unlike the OFR Report, the Consultative Document proposes assessing systemic importance at the fund-level, as opposed to at the asset manager-level with all funds combined (although the proposed designation criteria are similar).

The key takeaway in our view is that the Consultative Document’s publication, in and of itself, furthers the likelihood that a few, large US asset managers will ultimately be designated by the US’s Financial Stability Oversight Council (“Council”) as systemically important financial institutions (“SIFIs”). [2] The Consultative Document affirms the US’s position that the industry as a whole is systemically important, even after the Council revealed last summer its inclination to designate particular asset managers as SIFIs. [3] The Council will not need to “prove” that a particular firm is systemically important—rather the Council will assert broad discretion based on the flexible standard of what “could” happen under a worst-case-scenario, as we saw with the rationale for designating insurance companies last year.

The Council’s designation process, while fair on its face, is naturally inclined toward designation based on scenarios fraught with financial calamity. If the financial crisis had a central theme, it was the failure by regulators to understand the interconnectedness of key financial institutions across sectors and to utilize their tools to contain the crisis. In response, SIFI designation provides an increased understanding of the potential risks posed by large, complex financial firms of any credible stripe (including a further understanding of how to resolve such institutions). Designation also provides a better regulatory window into (and influence on) the “shadow” banking system.

Finally, the asset management industry, unlike banking and insurance, features a highly diverse and complex array of structures. At first glance, this structural complexity appears to present a barrier to one-size-fits-all designation methodologies for particular firms. As a result, some in the industry contend the Council may borrow from the Consultative Document by ultimately making US SIFI designations at the fund-level. However, in the US’s enhanced prudential standards (“EPS”) rule finalized last week, the Federal Reserve indicated it will “tailor” the EPS to firms such as insurers or asset managers which have a different risk profile than banks (e.g., with respect to balance sheet structure or regulation), which somewhat undermines the industry’s argument. [4] We believe that fund-level designation by the US is unlikely not only for this reason, but moreover because fund-level designation would narrow the regulatory window into these institutions and force the Council to further detail its designation approach (which it has not done extensively thus far).

This post analyzes the OFR report and the Consultative Document, and concludes with our continued view that the Council will propose a few large asset managers for designation.

Background

The development of the FSB/IOSCO Consultative Document was affirmed at the G20 Summit in St. Petersburg in September 2013 as another step toward implementing the FSB’s framework for reducing the risks posed by SIFIs. [5] Implementation of that framework requires, as a first step, identification of financial institutions that are systemically important on a global level, i.e., G-SIFIs. To that end, the Consultative Document follows similar issuances by the FSB and IOSCO on methodologies for extending the G-SIFI framework that currently covers global systemically important banks (“G-SIBs”) and insurers (“G-SIIs”) to ”all other financial institutions.”

Through the work of the Council, the US has led the global efforts toward designating nonbank financial institutions as systemically important in a manner that is generally consistent with that of the FSB and IOSCO. The Council issued its final rule on designating nonbank financial companies (“NFCs”) as SIFIs in April 2012, [6] and made clear at that time that it was considering whether certain asset management firms might be systemically important. To assist in that assessment, the Council asked the OFR to undertake a report on the systemic importance of the US asset management industry, which the OFR issued in September 2013.

In the US, the Council has two basic regulatory options with respect to NFCs—one resulting from designation of individual firms and another if any perceived systemic issues entail broader industry risks. If the Council designates an investment fund or other structure as a SIFI, it becomes subject to resolution and recovery planning requirements, Federal Reserve supervision, and the EPS, i.e., a bank-like approach that becomes more tenuous as the business of the nonbank SIFI looks less like a bank. Even with last week’s “tailoring” provision in the EPS rule, the Federal Reserve may still face challenges in tailoring a capital approach to designated asset managers (as has been the case for designated insurers) due to the reconciliation that must occur between the Collins Amendment’s capital floor and Section 165 of Dodd-Frank which allows the Federal Reserve to determine that capital requirements are not appropriate for certain NFCs. This unresolved tension is heightened by the EPS’s tailoring provision and will likely further fuel the movement to repeal or modify the Collins Amendment (an effort which we believe has been gaining some traction in Congress). [7]

The other option is the approach taken by the Council with respect to regulation of money market funds, i.e., the Council may recommend to the SEC that it pursue more stringent regulation of the asset management industry or its sectors. However, this option has all the subtlety of a blunt force object and expands the Council’s role more into the granularity of regulatory policy in a highly specialized and complex industry, and would likely generate substantial Congressional opposition. This approach is also subject to delay, as it took over six months for the SEC to propose its money market rule after the Council issued reform options in November 2012, and nearly another 9 months have since passed awaiting the SEC’s final rule. [8]

The industry opposes SIFI designation mostly because of the prospect of Federal Reserve regulation based on a bank-like model that is inapposite in many respects to other financial sectors. If the result of designation were more oversight and information to produce recommendations rather than the automatic imposition of another regulatory framework, the process would be less adversarial than it has become. For example, the Federal Reserve and SEC could be charged by the Council to recommend changes to existing SEC rules, supplemented by Federal Reserve oversight focused on interconnectedness. This type of approach however would require a revisiting of the designation provisions of Dodd-Frank—statutes cannot be wished away.

The OFR Report

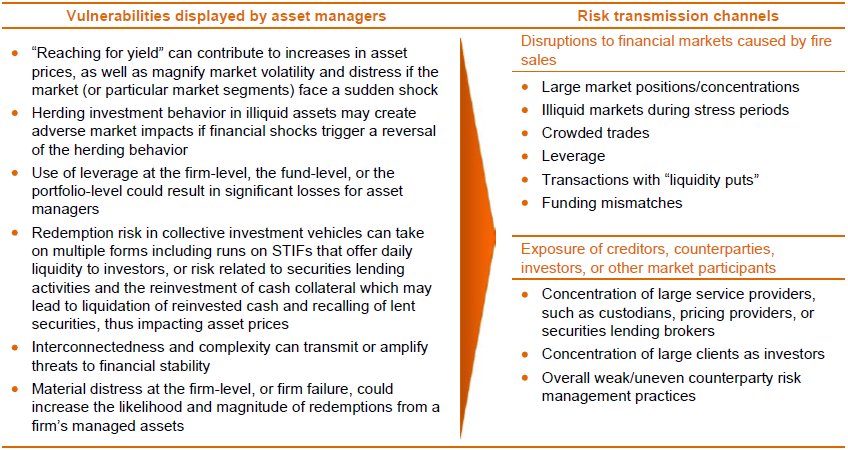

The OFR Report describes potential threats to US financial stability from asset managers’ activities. It analyzes the industry’s activities, describes factors that make the industry and its individual firms potentially vulnerable to financial shocks, and considers the channels through which the industry could transmit risk across markets during financial distress.

The OFR Report acknowledges that asset managers differ from banks and other NFCs in important ways. Specifically, the Report points out that asset management firms do not use their own assets or balance sheets to support their clients’ and funds’ investments. Nevertheless the Report notes important similarities between asset managers and banks—including that they both hold “money-like liabilities” that might expose asset managers to the same types of “runs” as banks and other NFCs.

The Report identifies risks that it believes make the industry and firms vulnerable to financial shocks. These include (1) reaching for yield, (2) herding behaviors, (3) redemption risk in collective investment vehicles, (4) leverage which can amplify asset price movements and increase the possibility of fire sales, and (5) risk within the firms themselves.

The Report then assesses the likelihood that in periods of stress the industry could transmit these risks across the financial system through two primary channels: (a) disruptions to financial markets caused by fire sales, and (b) exposures of creditors, counterparties, investors, or other market participants to an asset manager or asset management activity.

The following graphic depicts the OFR Report’s view of the industry’s vulnerabilities, along with the two channels through which these risks are primarily transmitted.

Because of these vulnerabilities and transmission channels, the Report concludes that “a certain combination of fund- and firm-level activities within a large complex firm” or “engagement by a significant number of asset managers in riskier activities” could pose, amplify, or transmit a threat to the financial system. These threats may be particularly acute when a small number of firms dominate a particular activity or fund offering.

Despite its conclusions, the Report’s scope is limited and subject to gaps in the underlying data. The Report does not address in detail hedge funds and private equity and other private funds, and excludes from its scope money market funds. The underlying data gaps exist particularly with regards to separate accounts, securities lending, and repo transactions.

These limitations and gaps are also acknowledged by the OFR in its 2013 annual report. The annual report repeats the OFR Report’s conclusions, re-acknowledges its shortcomings, and puts addressing data gaps in asset management activities among the OFR’s priorities in 2014 (if requested by the Council) including analyzing new data collected from private funds by the SEC.

Criticism of the OFR Report

Critics of the OFR Report have contended that (a) it shows an inaccurate understanding of the asset management industry, (b) it ignores the distinctions between asset managers and other financial institutions, and (c) it understates the extent to which the industry is currently regulated.

With regards to the first point, the Investment Company Institute (“ICI”) has argued that data from past periods of market stress contradict the Report’s conclusion about the industry’s vulnerabilities and its potential to pose systemic risk. The ICI has also suggested that the OFR has misused or misinterpreted data to support its pre-existing conclusion, for example by exaggerating the size of the US asset management industry by $25 trillion.

Although the Report acknowledges the differences between asset managers and other financial institutions (e.g., banks and insurers), the industry believes that the Report does not factor those differences into its analysis. Such differences, critics contend, undermine the Report’s key conclusion that asset managers could create or transmit risk across the financial system.

Finally, critics claim that the Report understates or ignores the industry’s existing regulatory regime, including the Investment Company Act, other federal laws, and related SEC regulations. For example, the industry has argued that existing regulatory requirements around daily asset valuations, liquidity, leverage, transparency and oversight, and other risk mitigating factors are not given due weight by the Report.

These industry concerns have been echoed by some regulators. SEC Commissioner Gallagher has labeled the Report “notorious,” and has expressed concern about the push by the Council and Federal Reserve into the SEC’s regulatory jurisdiction. SEC Commissioner Piwowar has also criticized the Report and claimed that the Council represents an “existential threat to the SEC.” SEC Chair Mary Jo White has even stated that although the SEC provided technical assistance to the OFR and commented extensively on the Report before its completion, the SEC and the OFR “agree to disagree on a number of things.”

The industry has also received support from lawmakers. In a January 23rd letter to Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, a bipartisan group of five senators criticized the Report, urging the Council to not use it as basis for any policy or regulatory action. The letter mirrors industry concerns, stating that the Report “mischaracterizes the asset management industry and the risks asset managers pose, makes speculative assertions with little or no empirical evidence, and, in some places, predicates claims on misused or faulty information.”

Similar concerns were voiced by other lawmakers during Congressional hearings on OFR’s annual report and oversight. During the Senate hearing on January 29th, for instance, members of the Senate Banking Subcommittee on Economic Policy criticized the Report for overstating the industry’s risks and ignoring regulations that are currently in place.

The OFR has responded to these criticisms by highlighting the Report’s acknowledgment of data gaps and the differences between asset management firms and banks. For example, the OFR’s 2013 annual report cites the differences between asset managers and banks (which the Report only mentions briefly) as a “cornerstone of the [Report].” Similarly, in his January 29th Senate testimony, OFR Director Richard Berner categorized those differences and data gaps as two of the Report’s three key findings (the third being that “vulnerabilities in some activities could give rise to threats to financial stability”).

The Consultative Document

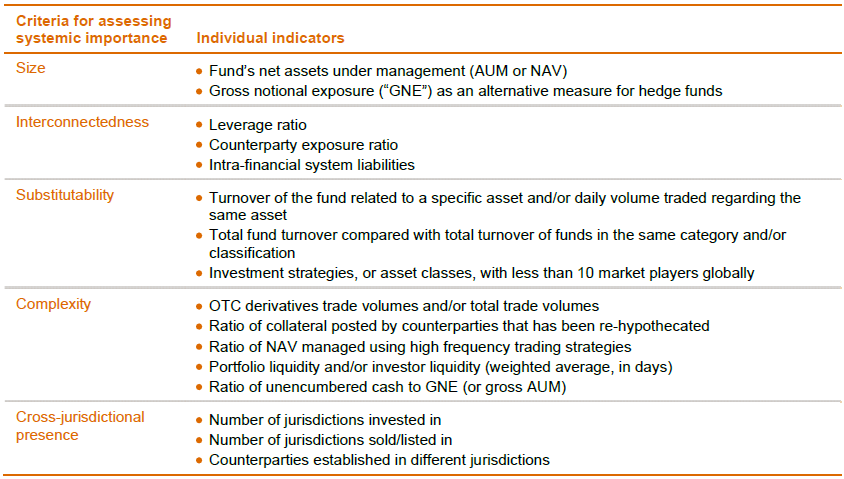

Similar to the OFR Report, the FSB/IOSCO Consultative Document identifies factors that make the asset management industry vulnerable to financial distress, and the channels through which the industry could transmit risk across the financial system. Although the Consultative Document takes a global rather than national view of the financial system, it proposes methods to measure systemic importance that are similar to those used in the Report and identifies the same two channels for transmission of risk from a fund across the financial system—namely, (a) exposure of counterparty, creditor, investors, and other market participants to a fund’s failure, and (b) fire sales that could disrupt financial markets.

The following table shows that the Consultative Document considers criteria for assessing systemic importance that for the most part are similar to the OFR Report. These criteria include size, interconnectedness, substitutability (i.e., investors’ access to multiple investment options), complexity, and cross-jurisdictional presence. The Consultative Document proposes individual indicators for each criterion to aid with assessing a fund’s systemic importance.

Despite these similarities, the Consultative Document recognizes fundamental differences between asset managers and other financial entities (e.g., banks) more so than the OFR Report does. The Consultative Document also discusses those differences in more detail, and recognizes some benefits arising from such differences, e.g., that funds may act as “shock absorbers” as investors absorb losses incurred by a fund, thereby mitigating the effect on the broader financial system.

But the Consultative Document differs most significantly from the Report by proposing that systemic importance be determined at the fund-level. The Consultative Document establishes a size threshold of $100 billion in net assets under management and an alternative threshold for hedge funds of gross notional exposure between $400 and $600 billion.

The Consultative Document sets out three reasons for its fund-level approach:

- First, economic exposures are created at the fund-level from the fund’s underlying portfolio of assets.

- Second, a fund is usually organized as a legal entity separate from its manager. Therefore, assets of the fund are not available to claims by the asset manager’s creditors.

- Third, regulations in the US and the EU already require submission of certain fund-level data by asset managers that could be leveraged by regulators in G-SIFI assessments.

This fund-level application of the Consultative Document’s methodology brings new considerations into the G-SIFI designation process. In particular, the Consultative Document notes that asset managers have access to fund-level liquidity management tools that may “dampen the global systemic impact of a fund failure.” These tools include swing pricing, anti-dilution levies, redemption gates, side-pockets, redemptions in kind, and temporary suspensions.

FSB and IOSCO have determined that this fund-level approach could be potentially broadened (toward the US’s direction), and requested public comments on several suggested alternatives. These alternatives include applying the assessment methodology at either of three levels: (a) family of funds (i.e., families/groups of funds following the same or similar strategy that are managed by the same asset manager), (b) asset manager on a stand-alone basis, and (c) asset manager and all assets under its management.

What’s next for asset managers?

The road ahead for asset managers that are potential G-SIFIs will be a long one, given the several outstanding steps remaining in the FSB/IOSCO process. First, FSB/IOSCO must form an International Oversight Groups (“IOG”) that will include representatives from different national authorities to compile the names of institutions that exceed the prescribed asset thresholds. From there, each national authority will assess those institutions within their jurisdictions, engage in an iterative process with the IOG to ultimately together decide which firms should be designated as G-SIFIs and publish a final list.

Furthermore, the Consultative Document is only a consultation and is FSB/IOSCO’s first document on asset manager designation. Importantly, the comment period remains open until April 7, 2014 regarding the fundamental question of what level to designate asset managers as G-SIFIs (e.g., at the fund-level or firm-level). For the GSIIs, it took over 18 months for the FSB framework to advance from its first document to final methodology and designations in July 2013.

Given how long the global process will take for asset managers, it is our view that the Council will propose US designations before FSB/IOSCO finishes its work. The US has already demonstrated its desire to lead and not be led by international institutions. The Council proposed US insurers for SIFI designation last summer before the FSB had completed its G-SII process, despite the vigorous lobbying efforts of the US insurance industry. Furthermore, media reports from November 2013 indicated that the Council has already agreed to study two particular US asset managers for potential SIFI designation.

US regulators already have a strong sense of which firms they would like to designate—based on learnings from the financial crisis and on their implementation of Dodd-Frank (including information received from the bank SIFIs through resolution plans and supervisory conversations). We continue to believe the Council will propose two to four US firms for designation in 2015.

Endnotes:

[1] Assessment Methodologies for Identifying Nonbank, Non-Insurer Global Systemically Important Financial Institutions (January 8, 2014). In addition to investment funds, the Consultative Document also proposes sector-specific methodologies for finance companies and market intermediaries.

(go back)

[2] See PwC’s Regulatory Brief, Nonbank SIFIs: Up next, asset managers (October 2013). Furthermore, recent press reports indicate that four major asset managers were recently asked to meet with global regulators in London to discuss their possible SIFI designation.

(go back)

[3] See PwC’s Regulatory Brief, Nonbank SIFIs: FSOC proposes initial designations—more names to follow (June 2013), in which we argued that the process surrounding the US’s proposed designation of two insurers as systemically important signaled that a few particular asset manager designations were likely in the future.

(go back)

[4] See PwC’s First Take, Enhanced prudential standards (February 2014).

(go back)

[5] SIFIs are institutions whose distress or disorderly failure, because of their size, complexity, and systemic interconnectedness, would cause significant disruption to the wider financial system and economic activity.

(go back)

[6] Subsequently, three NFCs were designated as systemically important by the Council in 2013, including AIG and Prudential Financial (both insurers), and GE Capital.

(go back)

[7] For more information on tailoring bank capital standards to NFCs and on the regulatory obligations that designated NFCs will face, see our Regulatory Brief cited in note 3. Section 165 of Dodd-Frank provides that the Federal Reserve may, in consultation with the Council, determine that capital requirements are not appropriate for an NFC because of the NFC’s conduct such as “investment company activities or assets under management.”

(go back)

[8] See PwC’s A Closer Look, Money market funds: The SEC’s long awaited proposal (July 2013). However, the SEC has recently made its strongest statements to date that it may take initiative on its own, perhaps in an effort to avert Council designation. SEC Chair Mary Jo White recently announced that she is considering “increased oversight of the largest asset management firms” including “stress testing [and] more robust data reporting.”

(go back)

Print

Print