Simon C.Y. Wong is an adjunct professor of law at the Northwestern University School of Law, and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. This post is based on an article that recently appeared in the Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law.

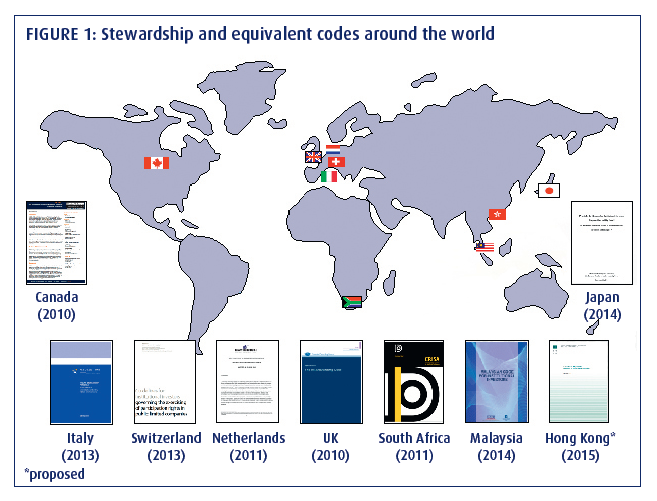

The idea that institutional investors should behave as active, long-term oriented “stewards” has caught on globally. Five years after the launch of the landmark UK Stewardship Code, counterparts can be found on four continents (see Figure 1).

When the UK code was promulgated, I argued that institutional investor stewardship was an elusive quest due to, inter alia:

- Inappropriate performance metrics and financial arrangements that promote trading and a short-term focus;

- Excessive portfolio diversification that makes monitoring of investee companies challenging;

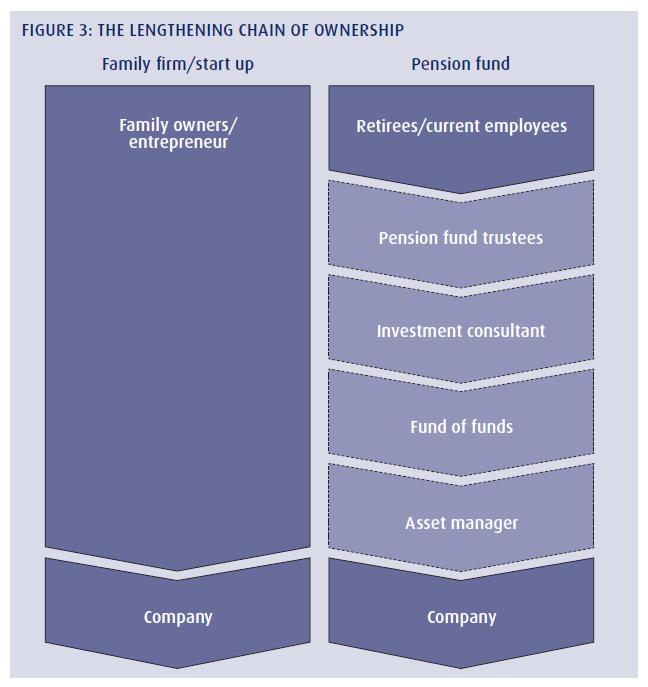

- Lengthening chain of ownership that weakens an ownership mindset;

- Passive/index funds that pay scant attention to corporate governance; and

- Pervasive conflicts of interest among asset managers.

The fifth anniversary of the UK code provides an opportune moment to examine the notable achievements and continuing challenges in the drive to encourage institutional investors to be informed and engaged owners.

In a nutshell, progress has been mixed and achieving broad-based institutional investor stewardship remains elusive. Promising developments have occurred largely at the asset owner level—particularly pension and sovereign wealth funds—rather than among the ranks of for-profit investment firms (“asset managers”) that invest the funds of asset owners.

To help spur improvements in investor behaviour, this post will highlight areas where substantive changes have taken place or are underway but readers should be under no illusion about success overall. Meaningful progress has proved hard to come by, hampered in part by the failure of stewardship codes to tackle head on the ailments highlighted above.

The Achilles Heel of Stewardship Codes

Stewardship codes are laudable initiatives but most suffer from a critical deficiency: They are largely devoid of substance.

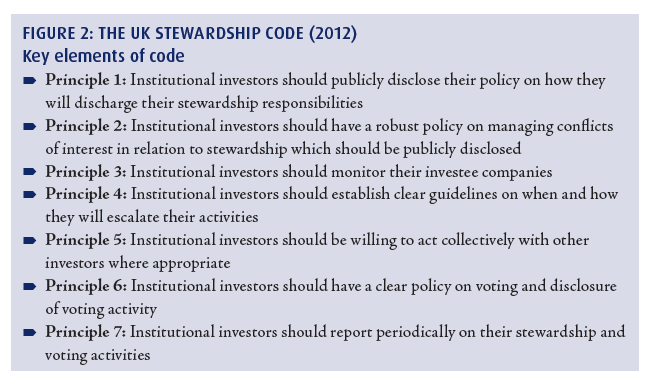

The UK Stewardship Code, for example, has generally failed to address the root causes of poor shareholder stewardship, opting instead to focus on process and mechanics (see Figure 2).

It is lamentable, therefore, that the UK Stewardship Code has served as a template—replicated almost verbatim in some cases—for counterpart guidance in such countries as Italy, Japan, and Malaysia.

The superficiality of stewardship codes extends to the misguided pursuit of as many signatories as possible. In the UK, code signatories now exceed 300, including approximately 200 asset managers. In Japan, where UK-style company-shareholder engagement is still relatively unfamiliar, nearly 200 institutional investors signed on in the first year of the stewardship code’s existence. While the high levels of take up make for good headlines, the crucial question is whether signatories have truly embraced stewardship.

The evidence accumulated in the UK suggests that the answer is clearly “no.” In its 2014 report on corporate governance and stewardship developments in the UK, the Financial Reporting Council sounded an alarm that “too many signatories fail to follow through on their commitment to the code.”

According to the head of corporate governance at a UK investment institution, “Of the roughly 300 members of the stewardship code, I would say there are only about 30 institutions that are doing the job properly.”

Notable Achievements and Continuing Challenges

While we have seen encouraging developments in a number of areas, stewardship deficiencies persist on most fronts.

Performance metrics and incentives

A long-term orientation is crucial to effective stewardship because engagement efforts typically bear fruit over time, and investment managers will be genuinely interested in creating value through engagement only if the metrics to assess their performance and the incentives they are given are commensurately long-term.

Yet, short-term, relative metrics—universally decried as detrimental to investor stewardship—remain no less prevalent in the investment industry.

To illustrate, 70% of the respondents to a 2013 CFA Institute survey of European investors cited short-period evaluation cycles by asset owners as an impediment to long-term investing. This is by far the biggest obstacle to adopting a longer investment horizon.

The problem is not that performance reviews occur at regular intervals but that they focus on short-term outcomes. A UK pension fund advisor cautions that “trustees shouldn’t look at quarterly performance figures because it will often lead to action but not always good decisions.”

Moreover, short-term financial incentives remain dominant. In a study published last year, the Centre for International Finance and Regulation reported that around 60% of investment managers have incentive structures based purely on short-term performance of one year or less.

Short-termism among investors can inflict considerable damage on investee companies. In a 2014 Stanford University survey of US investor relations executives, 65% of respondents expressed concern that companies whose shareholder bases are dominated by short-term investors are hindered in executing the business strategy and making long-term decisions.

Notwithstanding the above, some asset owners have taken a decidedly different path.

At a large North American pension fund, the chairman explained, “Our management, who has been delegated responsibility for monitoring external managers, look not just at the numbers during quarterly reviews. They focus on progress made against the originally agreed strategy. They also scrutinize the investment process, continuity of management, the motivation of fund managers and senior owners of the firm, and the quality of the relationship between them and us.”

Notably, some asset owners are emphasising absolute returns over relative comparisons. One Canadian pension fund is moving away from an obsession with performance versus benchmark, embracing instead Warren Buffett’s absolute return focus. It has also started to build into its investment model the possibility of never selling well-managed companies that provide attractive and steady returns.

Some institutions are also spearheading efforts to align compensation practices with long-term performance objectives.

The International Corporate Governance Network, for example, has produced a “model mandate” guidance encouraging “fund management firms to align their remuneration structures and cultures with the long-term perspectives which will generate returns over the time horizons that the asset owners need.”

Among large asset owners, one sovereign wealth fund, which lengthened the performance period covered by its incentive schemes from three to 10 years several years ago, is now experimenting with a 15-year scheme for top management that would remain in place even after an executive has departed the organisation. Although the 15-year scheme constitutes a small proportion of overall pay, its significance lies in making management more comfortable sitting through near-term losses and reducing portfolio managers’ temptation to trade on short-term factors.

At a North American pension fund with a sizeable in-house investment function, growing realisation that returns over 30-40 years matter most to beneficiaries has led to HR seeking to formulate pay policies for investment staff that extend the performance period far beyond the current four-year timeframe.

Crucially, improvements in this area require strong and competent governance. Sadly, many pension funds are still directed by trustees possessing inadequate investment expertise and who consequently over-rely on crude shortcuts—such as quarterly returns against a market benchmark—when evaluating asset manager performance.

According to a former senior executive of an Australian industry fund, “Like everyone else, we experience underperformance. But our independent directors, all of whom come with deep investment expertise, help other directors not to worry about short-term performance. At other funds, I don’t think this is always the case. Some appoint representatives to the board who lack relevant experience and want to sack investment managers based on near-term returns.”

The former CEO of a large US pension fund voiced a similar view, stating that “unsophisticated trustees have greater difficulties than sophisticated ones staying on the path.”

Size of portfolios

Despite warnings that diversification can be taken too far and growing evidence that concentrated portfolios outperform highly diversified ones, many institutional investors have continued to maintain unduly large holdings. A large US pension fund, for example, states that it owns shares in more than 10,000 companies globally while a European sovereign wealth fund has disclosed stakes in over 8,000 firms.

The equity portfolios of the biggest asset managers are likely to be even larger, with one declaring that it votes at more than 15,000 shareholder meetings annually.

For asset owners, large portfolios typically arise from investing in funds that track indices containing sizeable numbers of constituents as well as giving mandates to numerous asset managers. For example, one mid-sized UK pension fund has retained nearly 50 external fund managers even though a respected UK pension fund advisor has warned that 10 would likely be excessive for small to mid-sized schemes.

From a stewardship perspective, large portfolios make monitoring and engagement more challenging. In addition, having a multitude of investment managers means a pension fund may not be able to develop deep relationships with each of them and is more likely to focus inordinately on short-term, quantitative outcomes when assessing performance.

According to Railpen Chairman Paul Trickett, “If we want to be actively engaged with our managers and truly understand what they are doing we can’t do that across 50-odd managers.”

Encouragingly, some asset owners have started tackling the problem of excessive diversification, including through the creation of internally-managed concentrated portfolios.

Several years ago, an Asian sovereign wealth fund launched an in-house equity portfolio featuring 20-30 investments and low turnover. Furthermore, it has become more receptive to taking very large positions and serving as a long-term, “anchor” shareholder.

In Europe, a large industry pension fund has shrunk its equity portfolio by 70% to approximately 600 holdings and now takes larger stakes in smaller companies.

Reflecting the changing mindset, some asset managers have followed suit. As one UK investment manager stresses:

“We want to run focused portfolios containing companies that we really want to own. We are willing to take large stakes in these companies.”

In addition, some pension funds have trimmed their manager relationships. The CEO of a Nordic fund declares that “we would like to have fewer but deeper relationships. We want to better understand each external manager as a way to build trust and the foundation for a long-term relationship.”

“We are looking to reduce the number of external managers—having too many managers resulted in over-diversification,” echoes the CEO of an Australian industry fund. “Furthermore, by giving more funds to fewer managers, we believe we can negotiate lower fees.”

Ownership chain

As discussed in the 2010 stewardship post, Western equity markets have been plagued by increasing intermediation of ownership, with expanding layers of agents sitting between investee companies and their ultimate owners (see Figure 3). The resulting cascade of agency frictions contributes to the weakening of an ownership mindset essential for effective stewardship.

Fortunately, many asset owners are now seeking to contract the ownership chain. In a 2014 global survey of 134 pension executives, State Street found that 81% of pension funds were looking to increase the proportion of assets managed internally.

The motivation to manage assets in-house is not only to reduce costs but to better align interests. An Australian pension fund CIO explained that “by getting closer to the underlying assets, you reduce the impact of agency risks.” Notably, 52% of pension funds participating in the State Street survey found it challenging to ensure that their external fund managers’ interests are aligned with theirs.

The ownership chain is also contracting as “funds of funds”—which Yale investment chief David Swensen once derided as a “cancer on the institutional investor world”—become less influential. Across the globe, some large pension funds have eliminated these intermediaries, contributing to total assets under management of funds of funds declining from US$1.2trn in 2008 to around US$750bn in 2014.

In a few jurisdictions, asset owners have sought to ameliorate agency frictions by owning asset management arms. In Australia, where industry superannuation funds have built-up a suite of jointly-owned investment entities, one pension executive pointed out that “the establishment of the collective vehicles was very important for the industry in terms of addressing agency problems in the investment chain.”

Heavy reliance on investment consultants has also raised concerns, particularly as some are engaged in fiduciary and related fund management activities. Once again, investment expertise within the governing board and among staff can help alleviate agency frictions.

According to an Australian industry fund CEO:

“We have not retained an asset consultant for many years because we believe that our staff know as much as external advisers. Our investment committee acts as its de facto asset consultant.”

Passive/index investors

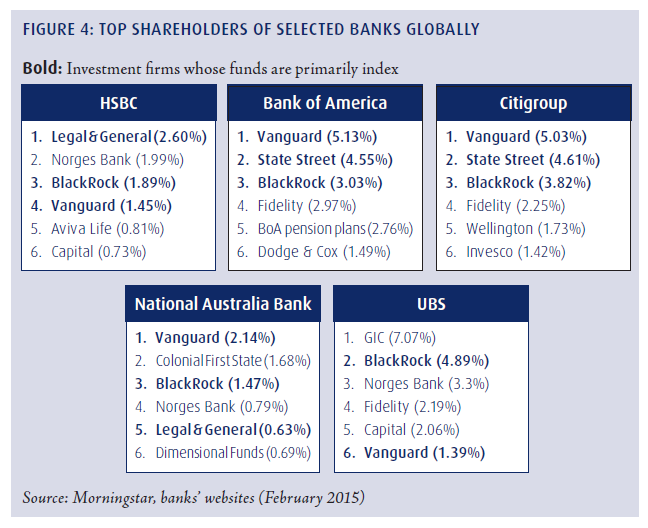

The past decade has witnessed the steady ascent of passive/index investment, such that the largest index houses are increasingly sitting atop the shareholder registers of large listed companies (see Figure 4).

Looking ahead, the footprint of index funds is expected to expand further. PwC predicts that passive/index investment will double its market share globally by 2020, reaching 22% (measured by assets under management) from 11% in 2012.

From a stewardship perspective, there has been a belated but welcome acknowledgement by several of the UK and US’s largest passive investment firms that “if you can’t sell, you must care.” Particularly in their home markets, it is not uncommon for index firms to wade into—and sometimes even lead—high-profile governance campaigns involving large listed firms.

Correspondingly, some company chairmen—viewing index investors as longterm shareholders who will stick with their firms through good and bad times—are proactively engaging them on matters of long-term significance.

The challenge for index institutions is that their portfolios are typically quite large and, due to resource constraints, there often exists a “long-tail of neglected companies.” A UK corporate governance veteran argues that it is “hard to say with confidence” that index houses “have enough resources to cover the waterfront.”

Of course, insufficient resources are a problem for most institutional investors. At a European sovereign wealth fund with 8,000 holdings, only a dozen employees staff its stewardship function.

Conflicts of interest

Pervasive conflicts of interest in the investment industry present arguably the most intractable obstacle to improving investor stewardship. As detailed in How Conflicts of Interest Thwart Institutional Investor Stewardship, they exist at the individual, firm, and group levels and create serious misalignments between asset managers and their clients.

Unfortunately, the UK Stewardship Code is particularly weak in this area. Whereas the Institutional Shareholders’ Committee Statement of Principles, upon which the UK Stewardship Code is modelled, called on institutional investors to have a policy on how conflicts of interest will be “minimised or dealt with,” the latter only emphasizes “identifying and managing” them, with no requirement to minimise or avoid them.

However, the 2012 Kay Review of UK Equity Markets and Long-Term Decision Making exhorts asset managers to “act at all times in the best long-term interests of their clients, informing them of possible conflicts of interest and avoiding these wherever possible.”

Globally, some stewardship codes have adopted a less tolerant stance. The Swiss guidelines for institutional investors declare that “institutional investors should avoid any conflicts of interest. In the event of unavoidable conflicts of interest they shall disclose them and take the necessary action to overcome them.” A similar formulation appears in the Malaysian Stewardship Code.

Concluding Thoughts

Developments over the past five years suggest that realisation of broad-based institutional investor stewardship will depend principally on asset owners. Nonetheless, asset managers can aid this effort by structuring the incentives of their investment staff to reinforce a long-term focus, shrinking their portfolios, and minimising conflicts of interest.

In addition, governments can play a stronger enabling role. For instance, to foster a longer investment horizon, asset owners have been urged to make a stronger commitment to their asset managers. Yet, in France, public pension funds are not permitted to contract with suppliers for longer than three years.

Lastly but crucially, stewardship codes can be made more effective by revamping their provisions to tackle the root causes of poor shareholder stewardship.

Print

Print