Jonathan C. Dickey is partner and Co-Chair of the National Securities Litigation Practice Group at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. This post is based on a Gibson Dunn publication.

The year was yet another eventful one in securities litigation, from the Supreme Court’s game-changing opinion in Omnicare regarding liability for opinion statements, to several significant opinions out of the Delaware courts regarding, among other things, financial advisor liability and the apparent end to disclosure-only settlements. This post highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the last half of 2015:

- Delaware courts put an end to so-called disclosure-only settlements, criticizing and then withholding approval for settlement agreements that provide a broad release of claims in exchange for additional disclosures (and, of course, fees for plaintiffs’ lawyers). That message was just recently reinforced by the Chancery Court’s opinion in In re Trulia Inc. Stockholder Litig. Whether, as many predict, this development will lead to a decline in merger objection litigation remains to be seen.

- Delaware courts issued several opinions that should be considered a warning to financial advisors that their disclosures of potential conflicts and their conduct in advising and informing boards throughout a sales process may be subject to increased scrutiny in Delaware.

- The Chancery Court found merger prices to be fair value in a trio of notable appraisal cases this year, rejecting management and expert cash-flow projections as unreliable.

- As for federal securities law developments, we highlight the Tenth Circuit’s opinion applying Omnicare—the only appellate court opinion to have reached opinion statement liability since the Supreme Court issued its opinion. We also highlight district court opinion applying the Omnicare analysis and note the circuits where post-Omnicare appeals are poised for resolution in 2016.

- In a similar vein, we analyze post-Halliburton II opinions below, including the Halliburton district court’s opinion and an issue posed for a possible Halliburton III.

- The Supreme Court heard oral argument in a challenge to the scope of Section 27 and whether a state court had jurisdiction over purported state law claims brought to enforce liability or duties created by the Exchange Act or rules and regulations thereunder. The briefs and oral argument are discussed in detail below.

We highlight these and other notable developments in securities litigation below.

Filing and Settlement Trends

New securities class action filings in 2015 showed a marked increase over prior years, and indeed represented the largest number of securities class actions filed in a single year since 2008. According to a recent study by NERA Economic Consulting (“NERA”), 234 class actions were filed in 2015, second only to the 247 cases filed in 2008. The mix of cases filed in 2015 also shifted heavily towards the technology sector, which experienced a 90% increase in new case filings versus the prior year total. The number of “merger objection” cases filed in 2015 also increased over the prior year, and represented approximately 18% of total cases filed in the federal courts. Cases naming financial institutions as the primary defendants were at the lowest level in this decade—only 10% of new cases filed, compared to the high-water mark of 2008, when 38% of all new cases named a financial institution as the primary defendant.

With respect to settlement trends, median settlements in 2015 were slightly higher than in 2014, while average settlement amounts increased dramatically. A wide range of cases, both big and small, comprised the population of settled cases: almost 60% of 2015 settlements were under $10 million, while roughly 20% were over $50 million. Most significantly, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses continue to reflect a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last ten years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded about 3% of total investor losses. In 2015, the percentage declined once again to 1.6%, or roughly half the ten-year high.

Filing Trends

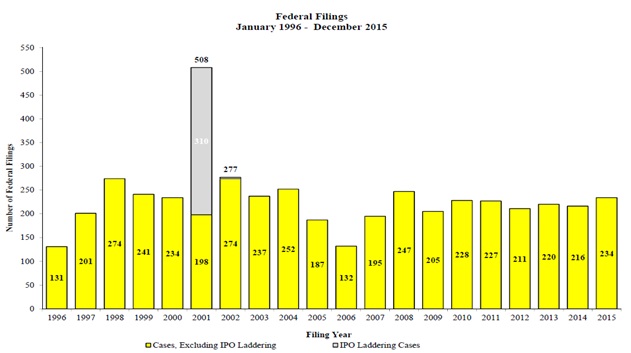

Overall filing rates are reflected in Figure 1 below (all charts courtesy of NERA). Two hundred thirty-four cases were filed in 2015. This figure does not include the many such class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Those state court cases, however, represent a “force multiplier” of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation in the United States today.

Figure 1:

Mix of Cases Filed in 2015

Filings By Industry Sector

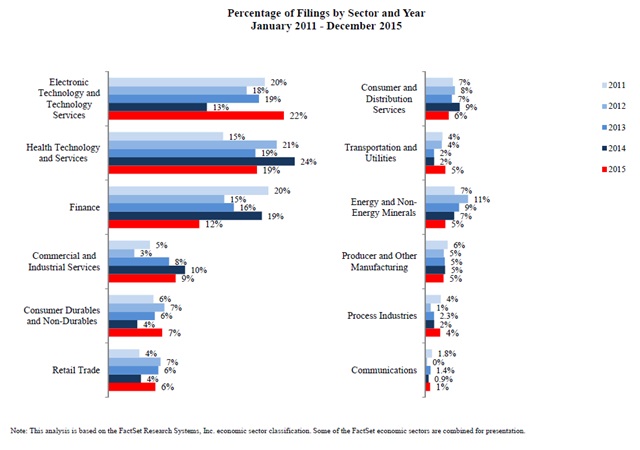

New case filings in 2015 reflect an enormous percentage increase in cases filed against companies in the technology sector, which led all industry sectors with 22% of all cases filed. The healthcare sector ranked second with 19% of all new cases, followed by the financial sector with 12%. Cases against defendants in the healthcare and finance sectors actually dropped year-over-year. The biggest percentage increase in new case filings in 2015 was in the transportation sector, where new filings more than doubled from their 2014 levels. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

Merger Cases

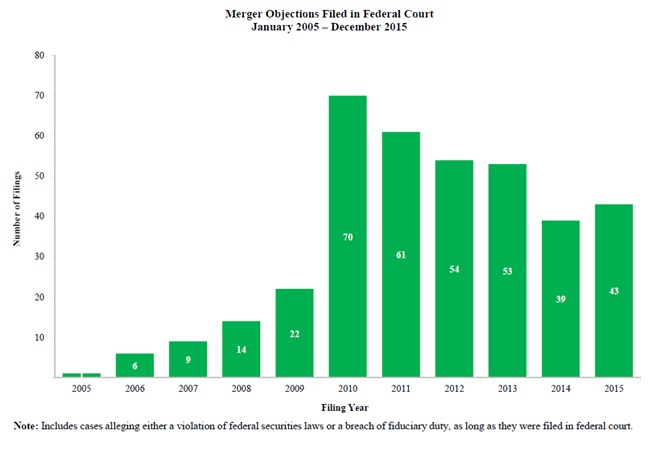

As shown in Figure 3, “merger objection” cases filed in federal court increased slightly from 39 cases in 2014 to 43 cases in 2015. Note, however, that this statistic only tracks cases filed in federal courts. The real action in M&A litigation is in state court, particular the Delaware Chancery Court. But as discussed below in our discussion of “Merger & Acquisition and Proxy Disclosure Litigation Trends,” the Delaware Court of Chancery has begun to express deep skepticism about these cases, and has started to reject settlements of M&A cases with no real substance.

Figure 3:

Settlement Trends

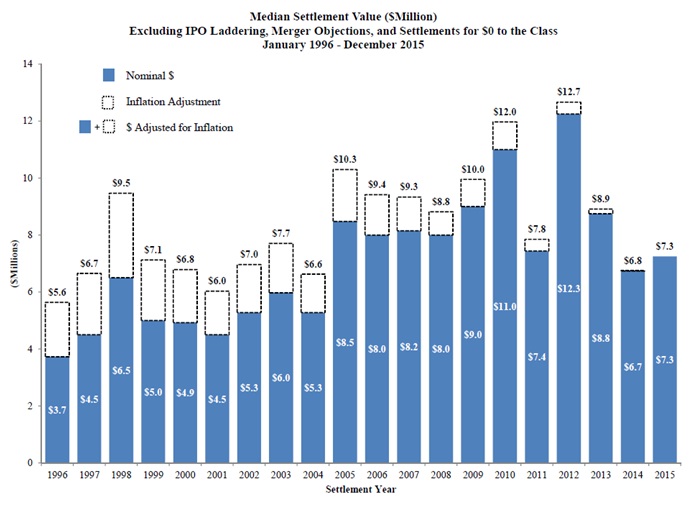

As Figure 4 shows, median settlements were $7.3 million in 2015, slightly higher than in 2014. One can speculate about what may account for the up-and-down trend in median settlements in the last few years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act or Section 11 of the Securities Act. Median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of one or more large settlements, any one of which can skew the numbers. In 2015, for example, the number of settlements above $100 million increased from 6% to 13% of all settlements. At the same time, the number of settlements below $10 million remained flat. This fact partially explains the overall increase in median settlement values in 2015.

Figure 4:

Whatever the variables, year-over-year movements in median settlement amounts do not necessarily indicate any long-term trend. Indeed, in the last decade, median settlement amounts have dropped in six out of ten years, and increased in four out of ten years.

Perhaps all that can be said of overall settlement trends is that plaintiffs’ lawyers continue to thrive. According to NERA, total attorneys’ fee awards in 2015 were in excess of $1 billion, representing a big increase from 2014’s total of $672 million. These astronomical amounts have become the “new normal,” as total fees over the last decade have ranged from a low of $671 million to a high of $1.7 billion, with the amounts in seven out of ten years exceeding $1 billion.

Delaware/Derivative Litigation Developments

The year 2015 continued to be an eventful one for Delaware courts, the state legislature, and derivative litigation generally. As discussed in our Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, there were important legal developments in the first half of the year regarding the defenses corporations and their directors have to breach of fiduciary duty claims, and several significant rulings concerning the standing of creditors to pursue derivative claims; director and officer advancement rights; and the ability to settle shareholder derivative claims by paying a special dividend to shareholders. Additionally, we noted that Delaware corporations are experiencing a new wave of shareholder “inspection demands” over so-called “dead hand proxy puts.”

Delaware developments picked up even more steam in the second half of this year with several significant developments, including rulings concerning financial advisor liability for aiding and abetting a director’s breach of a fiduciary duty, the difficulty of showing control before a transaction will be subject to the heightened entire fairness standard, and the Delaware Court of Chancery strongly signaled that stockholder class actions attacking mergers may no longer be resolved by a corporate defendant providing additional disclosures to stockholders (with payment of a fee to plaintiffs’ lawyers) in exchange for a broad release of claims against all defendants. Finally, the trend of merger price as “fair value” in appraisal cases continued in the latter half of 2015.

Delaware Courts Clarify Financial Advisor Liability for Aiding and Abetting a Director’s Breach of a Fiduciary Duty

The Rural/Metro Case

In a highly anticipated ruling, the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed a Chancery Court decision that directors breached their duty of care in connection with a sales process and that the Board’s financial advisor aided and abetted the breach. RBC Capital Markets, LLC v. Jervis (“Rural/Metro”), No. 140, 2015, C.A. No. 6350-VCL (Del. Nov. 30, 2015). The Chancery Court found fault in a special committee electing to put the company “in play” without the prior approval of the full board and with the board’s failure to properly supervise its financial advisor. In addition, the Chancery Court faulted the financial advisor for following its own financial interest in pursuing buy-side financing to impact the sales process, failing to adequately inform the board of the potential conflict, and providing a flawed financial analysis. The Chancery Court concluded that even though the directors would have been exculpated from liability for breaches of fiduciary duties, the financial advisor still could be held liable for aiding and abetting a breach.

The Supreme Court affirmed the principal holdings of the Chancery Court decision, offering several key takeaways. First, when directors breach their fiduciary duties in a sales process, the breach may be a sufficient predicate for aiding and abetting liability post-closing, even if the underlying breach of fiduciary duty cannot result in money damages under an exculpatory provision in the company’s charter. Second, while the Supreme Court’s decision provided no roadmap for a financial advisor’s disclosure of potential conflicts, the decision follows a long line of recent cases analyzing such conflicts. Thus, the decision follows other Delaware decisions that incentivize financial advisors to disclose all potential and actual conflicts of interest to boards both at the outset and throughout the engagement, and for boards to carefully scrutinize such conflicts. The decision makes clear that financial advisors do not have a “free pass” to engage in self-interested conduct at the expense of the board or company, even if the board consents to the conflict or potential conflict. Finally, the Supreme Court’s decision makes clear that while financial advisors must be careful not to create an “informational vacuum” that may lead the board to breach a fiduciary duty, the advisor does not act as a “gatekeeper” for the board in a sales process. In so ruling, the Supreme Court limited a principal (and much discussed) holding of the Chancery Court concerning the “gatekeeper” role of the financial advisor, but still ruled that financial advisors must ensure that boards are fully informed and proceeding on accurate information, and that an intentional failure to do so may provide the sufficient level of scienter to support an aiding and abetting claim.

The Tibco Case

In another decision addressing the duties of financial advisors in transactions, the Court of Chancery in In re Tibco Software Inc. Stockholders Litig., C.A. No. 10319-CB (Del. Ch. Oct. 20, 2015) elected not to dismiss a stockholder’s claim against Tibco Software Inc.’s financial advisor for aiding and abetting the board’s breach of the duty of care despite dismissing the underlying claim against the board. The court held that the plaintiff alleged facts that could support a non-exculpated claim for aiding and abetting, namely that the financial advisor knew the board was breaching its duty of care and participated in the breach by creating an informational vacuum.

The case arose out of a private equity firm’s agreement to purchase Tibco for $24 per share. In arriving at the share price, both parties relied on inaccurate information as to the number of fully diluted Tibco shares. Due to the miscalculation, the implied equity value of the deal was worth $100 million less to Tibco than both parties expected. After discovering the error, the board met with its financial advisor to reconsider its recommendation to stockholders and to consider possible re-negotiation with the buyer. According to the complaint, when the Tibco board was considering taking action, the financial advisor knew that the Tibco board had not adequately informed itself concerning the circumstances of the error and failed to disclose material information that the board could have used in its decision on how to proceed. The complaint alleged that the financial advisor did so in order to protect its fee in the transaction.

Like the Rural/Metro decision, Tibco serves as yet another reminder of increased scrutiny of financial advisors in Delaware and the heightened importance of financial advisors disclosing potential conflicts and keeping boards fully informed throughout a sales process.

The Beginning of the End of Disclosure-Only Settlements in Delaware

In a series of decisions issued during the second half of 2015, the Delaware Court of Chancery strongly signaled that stockholder class actions attacking mergers may no longer be resolved by a corporate defendant providing additional disclosures to stockholders (with payment of a fee to plaintiffs’ lawyers) in exchange for a broad release of claims against all defendants. These cases likely signal the end to what had been common practice in stockholder litigation routinely challenging mergers. As Vice Chancellor Glasscock put it in one recent ruling, expectations that the Court will approve such broad releases in exchange for additional disclosures “will be diminished or eliminated going forward.” In re Riverbed Technologies, Inc. Stockholders Litigation, C.A. No. 10484-VCG (Del. Ch. Sept. 17, 2015). These decisions will significantly impact the landscape of merger litigation in Delaware, possibly resulting in fewer strike suits filed in that jurisdiction and rendering such cases more difficult to resolve quickly and without motion practice.

In the first of this line of cases, Acevedo v. Aeroflex Holding Corp. et al., C.A. No. 9730-VCL (Del. Ch. Jul. 8, 2015), Vice Chancellor J. Travis Laster rejected a proposed settlement in which the defendant made additional disclosures, lowered the break-up fee, and reduced the matching rights period in exchange for a full release, finding that these changes did not increase the likelihood of a topping bid and therefore did not produce value for the shareholder class. On the same day, Vice Chancellor Noble in In re InterMune, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 10086-VCN (Del. Ch. Jul. 8, 2015) deferred ruling on whether to approve a settlement based on additional disclosures and attorney’s fees in exchange for a full release after expressing concern that the breadth of the release exceeded the scope of the plaintiffs’ claims.

Shortly following the Acevedo opinion, yet another order came down regarding challenges to a disclosure-only settlement. In re Riverbed Technologies, Inc. Stockholders Litigation, C.A. No. 10484-VCG (Del. Ch. Sept. 17, 2015) involved a settlement of litigation concerning a going-private transaction. While approving the settlement at issue because of “the reasonable reliance of the parties on formerly settled practice in this Court,” Vice Chancellor Glasscock warned that similar settlements–where the class obtained arguably minimal benefit in exchange for a global release–would not be approved going forward because such releases extend “beyond the claims asserted and the results achieved.”

Next, in In re Aruba Networks, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 10785-VCL (Del. Ch. Oct. 9, 2015), the court rejected a proposed class action settlement stemming from Hewlett Packard’s purchase of Aruba Networks. The Vice Chancellor characterized the case as a “harvesting-of-a-fee opportunity” because it lacked merit when filed, and he criticized the plaintiffs’ attorneys for failing to conduct sufficient investigation to determine whether there were actual problems with the transaction. Addressing disclosure-only settlements in general, Vice Chancellor Laster stated that “I think that we have reached a point where we have to acknowledge that settling for disclosure only and giving the type of expansive release that has been given has created a real systemic problem.” While acknowledging that he might have approved a settlement that released only disclosure-related claims, he rejected the settlement because the agreement would have released non-disclosure claims.

In re Silicon Image, Inc., C.A. No. 10601-VCG (Del. Ch. Dec. 9, 2015) the Chancery Court explicitly acknowledged its own altered approach to approving disclosure-only settlements. Vice Chancellor Glasscock approved a disclosure-only settlement in exchange for a broad release of claims, but described the matter as “a dying breed of cases” that is unlikely to receive Court approval in the future. He reiterated his view that equity should recognize parties’ reasonable expectations by evaluating settlements reached prior to the line of cases described in this post, but that settlements reached after these decisions will receive far greater scrutiny.

Finally and just days ago, in In re Trulia, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 10020-CB (Del. Ch. Jan. 22, 2016), the Chancery Court dealt what may be the final blow to disclosure-only settlements. Chancellor Bouchard rejected a disclosure-only settlement stemming from Zillow’s takeover of Trulia last year, explaining that “none of the supplemental disclosures were material or even helpful to Trulia’s stockholders,” and therefore the settlement did not afford the plaintiffs “any meaningful consideration to warrant providing a release of claims to the defendants.” Chancellor Bouchard noted that Trulia’s stockholders would not receive any financial benefit from the settlement, and that the only money that would change hands would be Zillow’s payment of fees to the plaintiffs’ lawyers. The decision likely signals the end of routine disclosure-only settlements in Delaware, as Chancellor Bouchard warned that the Chancery Court “will be increasingly vigilant in scrutinizing the ‘give’ and the ‘get’ of such settlements to ensure that they are genuinely fair and reasonable to absent class members.”

The Difficulty of Showing Control

A recent decision of the Delaware Supreme Court made clear the need to plead specific facts demonstrating the existence of a controlling stockholder before a transaction will be subject to the heightened entire fairness standard. In Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, No. 629, 2014 (Del. Oct. 2, 2015), the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Chancery’s dismissal of a class action by stockholders challenging the stock-for-stock acquisition of KKR Financial Holdings LLC (“Financial Holdings”) by KKR & Co (“KKR”). The plaintiff argued that the entire fairness standard of review presumptively applied to the transaction because KKR was a controlling stockholder of Financial Holdings since Financial Holdings’ primary business was financing KKR’s leveraged buyout activities and Financial Holdings was managed by an affiliate of KKR under a management agreement.

In dismissing the plaintiff’s claim, the Court held that the plaintiff failed to plead facts to support an inference that KKR was a controlling stockholder. The Court’s ruling was grounded on the fact that KKR owned less than 1% of Financial Holdings’ stock, had no right to appoint directors, and had no contractual veto right. Financial Holdings had real assets, an independent board, and investors that were fully informed of its unusual business structure. Without facts sufficient to establish the existence of a controlling stockholder, the Court held that the business judgment rule applied to the merger. The Court further concluded that the business judgment rule also applied because the transaction was approved by a fully-informed, uncoerced vote of the majority of disinterested shareholders.

Merger Price as Fair Value Continues to Hold in Appraisal Cases

In our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we discussed a series of stockholder appraisal cases in which the Chancery Court found that the “fair value” of stockholders’ shares following a corporate sale was the transaction price per share. In those cases—Merlin Partners LP v. AutoInfo Inc., C.A. No. 8509-VCN (Del. Ch. Apr. 30, 2015) and Longpath Capital LLC v. Ramtron Int’l, C.A. No. 8094-VCP (Del. Ch. June 30, 2015)—the Chancery Court rejected both management and expert cash-flow projections as unreliable, and looked to the merger price itself to determine fair value.

This trend continued in the latter half of 2015, most recently with Merion Capital LP and Merion Capital II LP v. BMC Software, Inc., C.A. No. 8900-VCG (Del. Ch. Oct. 21, 2015), which arose from the sale of BMC to a group of investment firms led by Bain Capital, LLC. Merion Capital LP and Merion Capital II LP acquired stock in BMC for the sole purpose of seeking appraisal in connection with the sale. Vice Chancellor Glasscock considered both sides’ expert appraisals and even conducted his own DCF analysis, but found none of them to be sufficiently accurate because all were based on “historically problematic” management projections with no reliable means of revision. The Court therefore found the executed merger price to be the best indicator of BMC’s fair value. This case reaffirms that where the court determines that a deal price was “generated by a process that likely provided market value,” the burden will be on any party challenging that valuation “to point to evidence in the record showing that the price must be adjusted from market value to ‘fair’ value.” Particularly where there is reason to doubt other means of valuation, the Chancery Court is likely to continue to rely on a fairly determined deal price as an indicator of fair value.

False Statements of Opinion Under Section 11 and Beyond: Omnicare and Its Ramifications

As we described in our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, in March the Supreme Court issued its long-anticipated opinion in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015). There, as also discussed in our client alert, the Court resolved a circuit split regarding the scope of liability for false statements of opinion under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933. Section 11 imposes liability where a registration statement “contained an untrue statement of a material fact or omitted to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading.” 15 U.S.C. § 77k(a). Unlike some other provisions of the securities laws that include a scienter requirement, Section 11 imposes essentially strict liability on issuers, and so a plaintiff “need not prove (as he must to establish certain other securities offenses) that the defendant acted with any intent to deceive or defraud.” Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1323.

The Supreme Court’s Opinion

The Supreme Court decided two questions in Omnicare: first, “when an opinion itself constitutes a factual misstatement,” and second, “when an opinion may be rendered misleading by the omission of discrete factual representations.” 135 S. Ct. at 1325. As to the first question, all nine Justices agreed that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong.” Id. at 1327 (majority opinion); see also id. at 1333-34 (Scalia, J., concurring); id. at 1337 (Thomas, J., concurring). Instead, an opinion statement is false only when the speaker does not “actually hold[] the stated belief,” or when the opinion statement contains an “embedded statement[] of fact” that is untrue. Id. at 1325-27 (majority opinion).

As to the second question, the majority held that an omission makes an opinion statement misleading under Section 11 where the omitted facts “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself[.]” 135 S. Ct. at 1329. That is so because “a reasonable investor may, depending on the circumstances, understand an opinion statement to convey facts about how the speaker has formed the opinion—or, otherwise put, about the speaker’s basis for holding that view.” Id. at 1328. An opinion statement therefore becomes misleading “if the real facts are otherwise, but not provided[.]” Id. “Thus, if a registration statement omits material facts about” the issuer’s basis for its opinion, “and if those facts conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the [opinion] statement itself, then § 11’s omissions clause creates liability.” Id. at 1329.

The Court emphasized, however, that “whether an omission makes an expression of opinion misleading always depends on context.” Id. at 1330. And the context of an issuer’s opinion statement includes “hedges, disclaimers, and apparently conflicting information” in the registration statement, as well as “the customs and practices of the relevant industry.” Id. Moreover, a Section 11 plaintiff bears the burden to “identify particular (and material) facts going to the basis for the issuer’s opinion—facts about the inquiry the issuer did or did not conduct or the knowledge it did or did not have—whose omission makes the opinion statement at issue misleading[.]” Id. at 1332. The Court noted that this “is no small task for an investor.” Id.

In a concurrence, Justice Scalia explained that he would have confined liability to situations where a speaker subjectively intends her opinion statement to mislead investors. Id. at 1336 (Scalia, J., concurring). But Justice Kagan, writing for the majority, responded that Section 11 imposes strict liability for material misstatements and omissions, and hence “discards the common law’s intent requirement.” Id. at 1331 n.11 (majority opinion). That Section 11 lacks a scienter requirement was therefore an important factor in how Omnicare was decided. Importantly, the Omnicare Court otherwise left unaddressed how its opinion applies to other securities laws that do require a plaintiff to establish scienter—for example, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and SEC Rule 10b-5.

Post-Omnicare Decisions

To date, only one court of appeals, the Tenth Circuit, has issued a substantive opinion applying Omnicare, though appeals are pending in the Second, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits. Meanwhile, several district courts have applied the Supreme Court’s decision in the context of Section 11 and beyond.

Post-Omnicare Decisions Under the Securities Act

Several district courts have applied Omnicare in cases that—like Omnicare itself—arose under provisions of the Securities Act of 1933 that impose essentially strict liability for material false statements or misleading omissions in offering documents.

In Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority v. Orrstown Financial Services, No. 1:12-cv-00993, 2015 WL 3833849 (M.D. Pa. June 22, 2015), the plaintiffs alleged that several of the defendants’ opinion statements were misleading under Section 11, including statements that a bank “had sound credit practices” and “had a strong balance sheet and management.” Id. at *19, *31. The court dismissed those claims, holding that for an opinion statement to “constitute something beyond corporate puffery,” the statement “must be in some way determinate or verifiable.” Id. at *31 (citing Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1326). The plaintiffs also alleged that an auditor’s statement was misleading under Section 11’s omissions clause, but that claim failed because the plaintiffs “offer[ed] little more than the conclusory assertion that [the auditor]’s opinions expressed in the Offering Documents ‘lacked a reasonable basis.'” Id. at *34.

The plaintiffs also lost in In re Velti PLC Securities Litigation, No. 13-cv-03889-WHO, 2015 WL 5736589 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 1, 2015), appeal filed, No. 15-17398 (9th Cir. Dec. 7, 2015). There, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendants’ opinion statements about a company’s bad-debt reserves were misleading under Section 11 because the defendants had omitted information about the company’s accounts receivable in Southeastern Europe. Id. at *21. The court dismissed that claim, holding that “the omissions clause does not create a ‘general disclosure requirement.'” Id. at *22 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1332).

And in Medina v. Tremor Video, Inc., No. 13-cv-8364 (PAC), 2015 WL 3540809 (S.D.N.Y. June 5, 2015), appeal filed, No. 15-2178 (2d Cir. July 1, 2015), the court held that the defendants’ registration statement was not misleading where it contained sufficient “‘hedges, disclaimers and qualifications’ addressing the risks associated with each statement of opinion.” Id. at *2 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1333).

The plaintiffs fared better in Federal Housing Finance Agency v. Nomura Holding America, Inc., No. 11cv6201 (DLC), 2015 WL 2183875 (S.D.N.Y. May 11, 2015), appeal filed, No. 15-1874 (2d Cir. June 10, 2015). There, the court held that the defendants’ stated belief that a company had followed underwriting guidelines was misleading under Sections 12 and 15 of the Securities Act because the defendants “‘lacked the basis for making those statements that a reasonable investor would expect.'” Id. at *103 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct at 1333).

Post-Omnicare Decisions Under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act

Several courts have applied Omnicare to claims brought under other securities laws, including Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5, which, like Section 11, prohibit misleading statements and omissions. Unlike Section 11, however, a Section 10(b) claim can range far beyond the offering documents and, critically, also requires a plaintiff to prove that a defendant acted with scienter. In re Kingate Mgmt. Ltd. Litig., 784 F.3d 128, 137 n.12 (2d Cir. 2015); see also Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1323.

As we reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, the Tenth Circuit applied Omnicare to a Section 10(b) claim in Nakkhumpun v. Taylor, 782 F.3d 1142 (10th Cir. 2015), holding that “[a]n opinion is considered false if the speaker does not actually or reasonably hold that opinion.” Id. at 1159. The Tenth Circuit, which remains the only court of appeals to have interpreted Omnicare, then held that the plaintiff was unable to establish scienter because the plaintiff had “not alleged any facts that would cast doubt on the sincerity or reasonableness of [the defendant]’s statement of his opinion.” Id. (citing Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1328-29). Thus, the court appears to have used Omnicare, which dealt with the question of when an opinion statement is objectively misleading under Section 11, to interpret Section 10(b)’s scienter requirement, which turns on a defendant’s subjective state of mind.

In Firefighters Pension & Relief Fund v. Bulmahn, Nos. 13-3935, 13-6083, 13-6084, 2015 WL 7454598 (E.D. La. Nov. 23, 2015), appeal filed, No. 15-31094 (5th Cir. Dec. 23, 2015), however, the court expressed doubt that Omnicare applied to the Section 10(b) claim before it: “That Omnicare concerned a strict liability statute suggests that the Supreme Court’s reasoning—which contemplates liability for statements of opinions that are genuinely held but misleading to a reasonable investor—does not directly apply to” Section 10(b). Id. at *25. Nevertheless, the court said that it would use Omnicare “as guidance” and “consider the relevant principles articulated in the Supreme Court’s decision.” Id. at *26. The court then held that the plaintiffs had failed to show that the defendants knew or were reckless in not knowing that their opinions were incorrect (i.e., the defendants lacked scienter). Id. at *30; see also, e.g., City of Westland Police & Fire Ret. Sys. v. Metlife, Inc., No. 12-cv-0256 (LAK), 2015 WL 5311196, at *16 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 11, 2015) (holding that opinion statements about life-insurance reserves were not misleading where the plaintiff failed to show that the defendants calculated the reserves in a manner different from what a reasonable investor would have expected); In re Amarin Corp., No. 13-CV-6663 (FLW) (TJB), 2015 WL 3954190, at *7 n.14 (D.N.J. June 29, 2015) (holding that an omitted fact did not conflict with what a reasonable investor would have taken from opinion statements and “assuming, without deciding, that Omnicare applies in the Section 10(b) context”).

In several other Section 10(b) cases, the plaintiffs convinced courts that defendants’ opinion statements were potentially misleading under Omnicare. For example, in In re Lehman Brothers Securities & ERISA Litigation, No. 09-md-2017 (LAK), 2015 WL 5514692 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 18, 2015), the court held that Omnicare‘s “reasoning applies with equal force to other provisions of the federal securities laws, including … Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5[.]” Id. at *5 n.48. The court then held that whether an auditor’s opinion statements about Lehman’s financial filings were misleading under Omnicare was one for the jury. Id. at *10. The court reasoned that “red flags” at Lehman could conceivably permit a jury to infer that the auditor did not actually believe the statements when it made them, or that its opinions were misleading to investors absent disclosure of the purported “red flags.” Id. In an apparent acknowledgement of the tension between Omnicare and Section 10(b), the court noted that whether a defendant’s statements “are made with the requisite scienter is, of course, another question.” Id. at *10 n.103;see also, e.g., In re Bioscrip, Inc. Sec. Litig., 95 F. Supp.3d 711, 730 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (holding that a reasonable investor could read a company’s statement of substantial compliance with the law as a guarantee that the company was unaware of serious investigations into its conduct); In re Petrobras Sec. Litig., No. 14-cv-9662 (JSR), 2015 WL 4557364, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. July 30, 2015) (holding that where defendants were aware of extensive corruption, plaintiffs’ allegations were sufficient to infer that defendants did not believe their stated opinion that internal controls were effective); In re Merck & Co., Inc. Sec., Derivative & “ERISA” Litig., Nos. 05-1151 (SRC), 05-2367 (SRC), 2015 WL 2250472, at *20-21, *23 (D.N.J. May 13, 2015) (holding that undisclosed data made the defendants’ opinion statements misleading under Omnicare and that Omnicare “illuminate[d]” the court’s Section 10(b) scienter analysis); In re Genworth Fin. Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 3:14-cv-682, 2015 WL 2061989, at *15 (E.D. Va. May 1, 2015) (holding that defendants’ reliance on outdated data made their opinion statements misleading under Omnicare).

We will continue to monitor closely Omnicare‘s application, and in particular its application in claims beyond Section 11, as we expect that courts will continue to grapple with this issue in 2016. Although most of the post-Omnicare activity has been at the district court level, appeals are now pending in the Second, Fifth, and Ninth Circuits that could provide greater clarity on the implications of Omnicare in other contexts.

Class Actions Post-Halliburton II: What Halliburton II Means in Practice and the Path to Possible Halliburton III

Through our three previous updates (here, here, and here), Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2398 (2014) (Halliburton II), remained the “case to watch.” In upholding the decades-old fraud-on-the-market doctrine enunciated in Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988), the Supreme Court made it clear that plaintiffs in securities class actions can still invoke the rebuttable presumption of reliance for class certification purposes, despite vigorous arguments by Halliburton and amici challenging the viability of the presumption in light of recent academic literature casting doubt on various theories about the efficiency of stock prices. See Halliburton II, 134 S. Ct. at 2408–10. But the Court also held that defendants in securities class actions have the opportunity to rebut the presumption of reliance by showing at the class certification stage that an alleged misrepresentation did not impact the defendant company’s stock price, id. at 2414, giving defendants an important tool to narrow the issues and limit exposure early on. Yet, the Court left open some key questions related to how the decision should be implemented. These questions include: whether traditional burden shifting under Fed. R. Evid. 301 applies, and if so, which party carries the burden of persuasion, what evidence is sufficient to show a lack of price impact, and whether the court can consider challenges to corrective disclosures in order to show lack of price impact.

In July 2015, the Halliburton district court issued its long-awaited decision on plaintiff’s motion to certify a class after considering both sides’ expert opinions and conducting a full-day hearing. We provided an overview of that decision in our August 2015 post. To recap, the district court certified the class as to only one of six alleged corrective disclosures. See Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 309 F.R.D. 251, 280 (N.D. Tex. 2015). This decision gave Halliburton a hard-fought victory and proved that the Supreme Court’s holding has teeth. As many predicted, the hearing was a battle of experts. The district court began its analysis by first considering two threshold legal issues—”(1) who has the burden of production and persuasion; and (2) whether [it] should, as part of the price impact inquiry, rule as a matter of law that particular disclosures are corrective.” Id. at 257–58. After lengthy analysis, the district court placed both the burdens of production and persuasion on the defendant and determined that it could not consider whether an alleged corrective disclosure was, in fact, corrective at the class certification stage. See id. at 260, 262. However, using expert evidence, Halliburton was able to avoid class certification on five out of six alleged corrective disclosures. Id. at 280.

As with many Supreme Court rulings, it may take some time for the lower courts to fully comprehend the implications of Halliburton II, but Halliburton’s experience on remand suggests that the opinion can be used to defeat class certification where the expert’s event study and opinions demonstrate that an alleged misstatement did not affect the price of the stock. Since the Supreme Court’s decision, the district court’s recent decision on remand represents one of several lower courts that have begun the process of interpreting Halliburton II. Also, the Fifth Circuit granted yet another Rule 23(f) interlocutory review to consider the Halliburton district court’s class certification as to the one remaining alleged corrective disclosure, which could possibly lead to Halliburton III. These decisions are beginning to shed light on some of the key questions surrounding how to implement Halliburton II.

“That was Not a ‘Corrective Disclosure'”—Path to Possible Halliburton III

Halliburton argued on remand that “each of the alleged corrective disclosures were not, in fact corrective.” Halliburton, 309 F.R.D. at 260. The district court characterized that part of Halliburton’s argument as “a veiled attempt to assert the ‘truth on the market’ defense,” which it concluded was relevant to materiality and not ripe for consideration at the class certification stage. Id. at 261. Instead, it rendered its decision assuming that “the asserted misrepresentations were, in fact, misrepresentations, and assum[ing] that the asserted corrective disclosures were [in fact] corrective of the alleged misrepresentations.” Id. at 262.

The district court’s interpretation is arguably at odds with the Supreme Court’s mandate to consider “any showing that severs the link” between the alleged misrepresentation and the stock price, but at least two other district courts to date have considered and rejected the same argument post-Halliburton II. See In re Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 10 Civ. 3461, 2015 WL 5613150, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 24, 2015); Aranaz v. Catalyst Pharm. Partners, Inc., 302 F.R.D. 657, 670–71 (S.D. Fla. 2014). In contrast, courts have generally been more receptive to arguments that the alleged corrective disclosure was already known to and digested by the market, regardless of the truth or falsity of the statement, than arguments that the alleged corrective disclosure did not actually correct a prior misstatement. The Supreme Court explicitly identified a showing that an alleged corrective disclosure was not “new” as a possible avenue to show a lack of price impact, Halliburton II, 134 S. Ct. at 2416–17, and the Halliburton district court itself found no price impact based on the market’s knowledge prior to the alleged correction, 309 F.R.D. at 272, 274 (finding no price impact where there was no announcement “that was not already impounded in the market price of the stock” before the alleged correction and where “[p]ublic announcements preceded Halliburton’s [allegedly corrective] press release”); see also In re Vivendi Universal, S.A. Sec. Litig., No. 02-cv-5571,—F. Supp. 3d—, 2015 WL 4758869, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 11, 2015) (citing Basic, 485 U.S. at 248) (observing that the showing that the defendant’s “statement correcting the misrepresentation was [already] made to, and digested by, the market” suffices to sever the link of price impact).

The Fifth Circuit is now set to weigh in on whether an argument that an alleged corrective disclosure was not, in fact, corrective of a prior misstatement is appropriate at the class certification stage. See Order Granting Mot. for Leave to Appeal under Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f), Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., No. 3:02-cv-1152 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 4, 2015), ECF No. 625. Notably, though, Judge Dennis explained in his concurrence why the district court was correct in light of Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 563 U.S. 804, 131 S. Ct. 2179 (2011) (Halliburton I) and Amgen, Inc. v. Conn. Ret. Plans & Trust Funds, 133 S. Ct. 1184 (2013), and stated that he concurred in granting leave to appeal so that “future litigants [can] benefit from the added clarity that [the court] can provide on this issue.”

How courts deal with alleged corrective disclosures is also at issue in the Best Buy case, as we discussed in our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update. Best Buy appealed—and the Eighth Circuit granted interlocutory review on—the class certification in IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., Inc., No. 11–429 (DWF/FLN), 2014 WL 4746195 (D. Minn. Aug. 6, 2014). One of the issues raised by Best Buy is whether an alleged misrepresentation was “corrective” where there is no factual nexus between the alleged corrective disclosure and the prior allegedly false or misleading statement. See Best Buy Br. for Permission to Appeal at 19–22, IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., No. 14-8020 (8th Cir. Aug. 19, 2014), appeal accepted, No. 14-3178 (8th Cir.). The Best Buy court heard oral argument on October 22, 2015, but it has yet to issue an opinion. As discussed in our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we also await the Second Circuit’s decision related to loss causation in In re Vivendi Universal, S.A. Sec. Litig., No. 15-108 (2d Cir.). Oral argument is scheduled for March 3, 2016. We will provide updates on these upcoming cases as they develop.

Does Traditional Burden Shifting Apply to Rebutting the Fraud-on-the-Market Presumption?

As mentioned above, the Halliburton district court placed both the burdens of production and persuasion on Halliburton, despite Halliburton’s argument that Federal Rule of Evidence 301 directs that the burden of persuasion rests with plaintiff; the court reasoned that the fraud-on-the-market presumption, which is unique to securities class action litigation, entitles the plaintiff to prove price impact indirectly, and the court could not reconcile a literal application of Rule 301 with the Basic presumption. Halliburton, 309 F.R.D. at 259–60 (reasoning that literal application of Rule 301 would eviscerate the fraud-on-the-market presumption, requiring plaintiff to prove reliance without the aid of the presumption and dooming class certification). The Halliburton district court is not alone in reaching this conclusion. See, e.g., City of Sterling Heights Gen. Emps.’ Ret. Sys. v. Prudential Fin., Inc., No. 12–5275, 2015 WL 5097883, at *12 (D.N.J. Aug. 31, 2015) (explaining that the presumption provides plaintiffs “an indirect way of showing price impact” which is inconsistent with placing burden on plaintiffs).

A few other courts have mentioned the standard for rebutting the presumption, without elaboration, but no clear standard has emerged describing defendant’s burden to “rebut” the fraud-on-the-market presumption by showing lack of price impact. See, e.g., In re Goldman Sachs, 2015 WL 5613150, at *4 n.3 (“Defendants must demonstrate a lack of price impact by a preponderance of the evidence.”); Wallace v. Intralinks, 302 F.R.D. 310, 317–18 (S.D.N.Y. 2014) (observing that “[d]efendants bear the burden to show a lack of price impact” and rejecting defendant’s rebuttal attempt where “Defendant has not shown that unrelated factors account for the[] price movements”); Aranaz, 302 F.R.D. at 673 (defendant failed to show “no unexpected events negatively affect[ed] … stock price” “[n]otwithstanding that Defendants have the burden of rebutting the presumption of price impact”); McIntire v. China MediaExpress Holdings, Inc., 38 F. Supp. 3d 415, 434 (S.D.N.Y. 2014) (“The defendant bears the burden to prove a lack of price impact.”).

Despite these early decisions, the allocation of the burden of persuasion should not be considered established. The Eighth Circuit is poised to weigh in on this debate and to possibly shed light on what plaintiffs would be required to do to carry the burden of persuasion in its forthcoming decision in the Best Buy case. There, Best Buy argued “[b]ecause the plaintiff has the ultimate burden of demonstrating that Rule 23’s requirements are met, [Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Dukes, 131 S. Ct. 2541, 2551 (2011)], once the defendant produces evidence to rebut the presumption of reliance, class certification must be denied unless the plaintiff shows by a preponderance of the evidence price impact of the alleged misstatements.” Best Buy Br. for Permission to Appeal, supra, at 13.

What Evidence Demonstrates a Lack of Price Impact?

There is no set playbook for making a “showing that severs the link between the alleged misrepresentation and either the price received (or paid) by the plaintiff, or his decision to trade at a fair market price,” see Halliburton II, 134 S. Ct. at 2408 (citing Basic, 485 U.S. at 248) (internal quotation marks omitted), but recent cases provide some guidance. Detailed and statistically reliable event studies will be the key tool. See Carpenters Pension Trust Fund of St. Louis v. Barclays PLC, 310 F.R.D. 69, 86, 94–97 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (observing that “an event study or other rebuttal evidence” would be “required” in the defendant’s rebuttal of the presumption and noting the defendant’s failure to submit its own event study in holding that the defendant failed to rebut the presumption); see also Halliburton, 309 F.R.D. at 264–65 (analyzing experts’ event studies before concluding that the defendant rebutted the presumption as to five out of six alleged corrective disclosures). But there is more to keep in mind for securities-litigation defendants.

Defendants have been most successful by addressing all of the possible stock price movements associated with plaintiffs’ alleged misrepresentations to show that the alleged misrepresentations carried no price impact and not merely pointing out potential alternative causes of a stock price change. Likewise, merely attacking plaintiff expert’s failure to show price movement on the alleged misrepresentation date is likely insufficient. See Barclays, 310 F.R.D. at 95 (explaining that “the failure of an event study to disprove the null hypothesis with respect to an event does not prove that the event had no impact on the stock price”). In the Halliburton II remand, the defendant’s expert report provided extensive analysis of the alleged price declines on the corrective disclosure dates and successfully demonstrated lack of price impact for five out of six dates. See Halliburton, 309 F.R.D. at 262–64 (describing Halliburton expert’s extensive studies and findings). Her analysis used economic principles that generally apply to securities class actions, along with complex statistical analyses that are sometimes required by particular situations. See Jorge Baez et al., NERA Economic Consulting, Update on Economic Analysis of Price Impact in Securities Class Actions Post-Halliburton II (Aug. 12, 2015). By contrast, one district court recently held that defendants failed to rebut the presumption because they “cannot show that the total decline in the stock price on the corrective disclosure dates is attributable simply to the market reaction to [alternative causes of stock price change proffered] and not to the revelation to the market that [the defendant] had made material misstatements about its conflicts of interest policies and business practices.” In re Goldman Sachs, 2015 WL 5613150, at *6; see also Barclays, 310 F.R.D. at 95 (rejecting a defendant’s argument that the plaintiff’s expert’s “failure to show price impact … is sufficient evidence to show lack of price impact”). Significantly, Halliburton’s expert on remand did not just attack the plaintiff’s expert’s methodology and conclusions; she affirmatively showed the court a lack of price impact. See Halliburton, 309 F.R.D. at 269–80.

Defendants have been less successful with no-price-impact arguments that hinge on a plaintiff’s failure to show loss causation or materiality. See Halliburton I, 131 S. Ct. at 2183 (plaintiff need not prove loss causation at the class certification stage to invoke the fraud-on-the-market presumption); Amgen, 133 S. Ct. at 1191 (same for materiality); see also City of Sterling Heights, 2015 WL 5097883, at *11 (rejecting the defendant’s argument that the stock price drop was caused by other contemporaneous disclosures as an argument that hinges on loss causation, which is distinct from price impact).

Despite this early guidance from lower courts, what Halliburton II means in practice is not set in stone. We will keep an eye out for further developments.

U.S. Supreme Court Prepares to Decide Circuit Split Over Whether Federal Courts Have Jurisdiction Over State Law Claims Related to “Naked” Short Sales

As we reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, on June 30, 2015, the Supreme Court continued its recent trend of taking up important securities law issues and agreed to hear the appeal in Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Manning, which concerns the jurisdictional scope of Section 27 of the Exchange Act. The case originated in New Jersey Superior Court, where plaintiffs alleged that a group of financial institutions violated New Jersey state laws by engaging in “naked” short-selling of shares of Escala Group, Inc. Although the complaint did not assert a claim under the federal securities laws, it referenced Regulation SHO, the SEC’s rule on short-selling. Defendants removed the case to federal court, arguing that Section 27 grants federal courts exclusive jurisdiction over suits alleging violations of the Exchange Act, and that the instant suit was necessarily premised upon enforcement of the Exchange Act despite asserting only state law claims. The district court agreed with defendants and denied plaintiffs’ motion to remand, but the Third Circuit reversed, holding that plaintiffs had not alleged a violation of Regulation SHO or the Exchange Act and no question of federal law was necessarily implicated by plaintiffs’ suit. Manning v. Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 772 F.3d 158 (3d Cir. 2014). Defendants petitioned the Supreme Court for certiorari. Presented with a split over the proper interpretation of Section 27 between the Second and Third Circuits, on one hand, and the Fifth and Ninth Circuits, on the other, the Supreme Court agreed to consider this procedural and jurisdictional question.

Defendants-Petitioners filed their brief with the Supreme Court on September 3, 2015. Petitioners relied extensively on Section 27’s plain language, which states that federal courts “shall have exclusive jurisdiction” over suits brought to enforce any liability or duty created by the Exchange Act or the rules and regulations thereunder, to argue that state courts are barred from hearing these claims. Brief of Petitioner-Appellant at 19-20, Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Manning, No. 14-1132 (Sept. 3, 2015). The complaint alleged violations of Regulation SHO—although it did not assert an independent claim on that basis—and petitioners thus argued that federal courts alone must hear plaintiffs’ case. Petitioners also likened Section 27 to similar language in other statutes already found to grant jurisdiction, which state that federal courts “shall have jurisdiction.” Id. at 28-29. In addition, petitioners argued that the legislative intent behind Section 27 was to ensure that federal courts provide uniform interpretation of the Exchange Act, which could occur only if federal courts were granted exclusive jurisdiction over suits raising Exchange Act issues. Id. at 25. Finally, petitioners refuted respondents’ argument from an earlier brief that the jurisdiction granted by Section 27 was entirely subsumed within the standard “federal question” jurisdiction granted by 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Id. at 33-34. In petitioners’ view, Section 1331 has been interpreted narrowly to avoid inundating federal courts with questions of state law, but Section 27 evinces a different, broader federal interest in placing Exchange Act issues exclusively with federal courts. Id. at 35-36.

Plaintiffs-Respondents filed their brief on October 23, 2015. Respondents’ central argument was that their suit presented only state law claims and Section 27 does not strip a state court of jurisdiction over those claims because of a “mere possibility” that an issue related to the Exchange Act might arise. Brief of Appellee-Respondent at 26-27, Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v. Manning, No. 14-1132 (Oct. 23, 2015). Moreover, respondents maintained that any reference in the complaint to Regulation SHO was offered as evidence to support their state malfeasance and RICO claims, and not to assert an actual violation of federal law. Id. at 30-31. In other words, simply referencing a federal regulation in the complaint does not turn a state law claim into a federal one. Respondents also noted that many states have laws paralleling the federal securities laws, and a plaintiff could properly choose to invoke the state form of relief without necessarily raising questions of federal law and invoking federal jurisdiction. Id. at 31-32. Finally, respondents contested petitioners’ distinctions between Section 27 and Section 1331, contending that Supreme Court precedent has repeatedly established their synonymous meaning. Id. at 37.

On December 1, the Supreme Court heard oral argument. Many of the justices—across the political spectrum—skeptically questioned petitioners’ counsel about why a case belongs in federal court if the face of the complaint only references federal law and does not assert any federal claim. Justice Kennedy also expressed concern that petitioners’ position could burden district court judges by requiring them to conduct searching examinations of state law claims to determine if they included violations of the Exchange Act. Justice Breyer noted that the SEC did not join petitioners’ arguments, suggesting that the U.S. government did not have an interest in having state law claims like those asserted by respondents heard in federal court. Respondents’ arguments also met with some skepticism by the Court. While respondents urged the Court to leave state courts to adjudicate issues of state law, the Court pressed respondents about why they included references to Regulation SHO in the complaint if they only sought to enforce state law. Respondents’ counsel explained that the references to the regulation were intended to preclude petitioners from asserting a preemption defense. Specifically, respondents wanted to ensure that petitioners could not try to argue that because they had complied with Regulation SHO, state law remedies were conflict-preempted and the case, therefore, had to be dismissed.

If the Court rules in defendants-petitioners’ favor, the jurisdiction of federal courts could be meaningfully expanded, as the relevant language used in Section 27 is also present in other federal statutes, such as the Natural Gas Act and the Federal Power Act. Plaintiffs could also find it increasingly difficult to have claims that even arguably implicate the Exchange Act heard in state court. By contrast, if the Court finds in favor of plaintiffs-respondents, there is a risk that plaintiffs may engage in increased forum shopping and artful pleading in attempts to avoid federal court. State courts may also develop a patchwork of conflicting precedent on issues that concern the Exchange Act and the SEC’s related regulations, subjecting future defendants to uncertain risks of liability.

Fifth Circuit Decision in Ludlow v. BP: An End to Securities Class Claims Based on Materialization-of-the-Risk Theory?

A recent federal court of appeals opinion dealt a blow to securities class action plaintiffs, casting significant doubt on the viability of class claims based on the materialization-of-the-risk theory. In Ludlow v. BP, P.L.C., 800 F.3d 674 (5th Cir. 2015), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed the holding of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas that denied class certification to one class of BP investors over alleged market losses resulting from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Although the Fifth Circuit upheld the class certification of one sub-class based on a “stock-inflation” model for investors who purchased BP stock after the oil spill, it most notably affirmed the denial of class certification based on the “materialization-of-the-risk” model for investors who purchased BP stock before the oil spill (“Pre-Spill plaintiffs”). The Pre-Spill plaintiffs alleged that purported misrepresentation of the risk of a catastrophic event, such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and the company’s preparedness to prevent and react to such an event, led to investor losses. Plaintiffs argued that these losses were measured by “the entire fall in stock prices caused by materialization of the risk of the spill.” Id. at 680. (emphasis original). The Fifth Circuit reasoned that misrepresentation of risk-level does not satisfy the requirement from Comcast v. Behrend, 133 S. Ct. 1425, 1433–34 (2013) that the plaintiffs’ model of damages must be “susceptible of measurement across the entire class.” Ludlow, 800 F.3d at 683. This ruling may foreclose—at least in the Fifth Circuit—securities class actions based on “materialization-of-the-risk” theories and, more generally, may also deter class claims alleging misleading disclosures regarding risk and uncertainty.

Under Comcast, a court must “conduct a rigorous analysis” to “establish[], before a class could be certified, congruence between theories of damages and liability.” Id. at 686 (citing Comcast, 133 S. Ct. at 1433). The purpose of this analysis is to ensure that the damages model “measures only those damages attributable to [the theory of liability].” Id. (quoting Comcast, 133 S. Ct. at 1433). As the Fifth Circuit explained, despite the holding in Halliburton I, that plaintiffs need not prove loss causation at the certification stage, Comcast nonetheless requires that a court evaluate the damages model to determine if, conceptually, it could isolate economic loss directly attributable to the claimed misstatements. See id. at 687. Striking a balance between Comcast and Halliburton I, the Fifth Circuit held that the Pre-Spill plaintiffs’ theory could not adequately isolate the economic loss resulting from the alleged misrepresentation. Id. In this case, the materialization-of-the-risk theory “hinges on a determination that each plaintiff would not have bought BP stock at all were it not for the alleged misrepresentations—a determination not derivable as a common question, but rather one requiring individualized inquiry.” Id. at 690 (emphasis original). Key to the plaintiffs’ theory of recovery in a materialization-of-the-risk case is the materiality of the risk disclosures: the theory is that investors would not have invested had they known the true degree of risk. However, the court reasoned, each plaintiff’s risk tolerance may differ, and those plaintiffs that may have purchased BP stock even had they known the “true” risk “cannot be compensated for the materialization of a risk [they] may have been willing to take.” Id. at 691. Thus, because the Pre-Spill plaintiffs’ damages model could not distinguish between those plaintiffs who would have taken a risk on BP regardless and those who would not, “it cannot provide an adequate measure of class-wide damages under Comcast.” Id. at 690.

Plaintiffs attempted to parlay the fraud-on-the-market presumption of reliance into a related presumption of loss causation. Id. at 691. They “argue[d] that if the[y] … prove the prerequisites of fraud on the market—which they have done—it is presumed that the Pre-Spill Class relied on BP’s misrepresentations in purchasing the [stock] and the misrepresentations were a cause-in-fact of their losses.” Id. The Fifth Circuit rejected this theory. If Basic‘s requirements are satisfied, the fraud on the market theory creates a rebuttable presumption that the plaintiffs satisfied transaction causation—that they relied on the alleged misrepresentation in entering into the securities transaction. But even assuming the class relied on the risk disclosures, that reliance did not necessarily result in economic loss. Id. The court went so far as to posit that the materialization-of-the-risk theory would necessarily rebut the presumption of reliance. Fraud-on-the-market presumes that “the market price of shares traded on well-developed markets reflects all publicly available information, and, hence, any material misrepresentations,” id. at 681, and that “investors typically make investment decisions based upon price and price alone.” Id. at 691 (emphasis in original). Plaintiffs’ materialization-of-the-risk theory urges on the other hand that investors relied on the risk disclosures in deciding to purchase the security. As the Fifth Circuit explained, the plaintiffs’ own theory undermined the presumption’s rationale. Id.

The Fifth Circuit’s decision in Ludlow provides a clear victory against purported class actions based on materialization-of-the risk theories and should be instructive to litigants in other securities fraud cases. If Ludlow‘s well-reasoned analysis will have a broader application to other theories where plaintiffs allege misleading disclosures involving future uncertainty, only time will tell.

SLUSA after Chadbourne

In our March 2014 post, we discussed Chadbourne & Parke LLP v. Troice, 134 S. Ct. 1058 (2014), in which the Supreme Court clarified the standard for applying the Securities Litigation Uniform Securities Act (“SLUSA”) to bar state law claims based on “a misrepresentation or omission of a material fact in connection with the purchase or sale of a covered security.” 15 U.S.C. § 78bb(f)(1) (emphasis added). In Troice, the Court held that the phrase “in connection with” required that the misrepresentation or omission must be “material to a decision by one or more individuals (other than the fraudster) to buy or sell a ‘covered security.'” 134 S. Ct. at 1066. In this year’s Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we discussed the Second Circuit’s narrowing of the scope of SLUSA preemption in In re Kingate Management Limited Litigation, 784 F.3d 128 (2d Cir. 2015), which applied a “necessary component” test for preemption, requiring courts “to inquire whether the allegation [of misrepresentation or omission] is necessary to or extraneous to liability under the state laws.” Since that time, courts have continued to consider the contours of SLUSA preclusion.

The Second Circuit recently turned to the issue of SLUSA preclusion again in R.W. Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of Pennsylvania v. Meridian Capital Partners, Inc., No. 15-1064-CV, 2015 WL 8731547 (2d Cir. Dec. 15, 2015). In Meridian Capital, the appellant purchased shares in a fund of hedge funds offered by the appellees, who ultimately lost these funds in the Madoff Ponzi scheme. Although the appellant had brought individual claims that would not otherwise have been barred by SLUSA, the Second Circuit upheld the district court’s dismissal of state and common law claims under SLUSA, holding that the appellant’s claims were “part of a ‘covered class action’ because they were ‘joined, consolidated, [and] otherwise proceed[ed] as a single action’ with a covered class action after they were officially consolidated by the district court in a consolidation order.” Id. at *3 (quoting 15 U.S.C. § 78bb(f)(5)(B)(ii)). Moreover, following the decision in Kingate, the court found the claims precluded because the appellant’s state law claims also were “premised on false representations Appellees are alleged to have made in connection with its due diligence procedures” concerning funds which purported to invest in covered securities. Id.

The United States District Court for Southern District of New York also recently decided another case arising out of the Madoff Ponzi scheme. In Anwar v. Fairfield Greenwich Ltd., No. 09 Civ. 118 (VM), 2015 WL 4610406, at *2-4 (S.D.N.Y. Jul. 29, 2015), the court first examined the relevant standard of review for SLUSA dismissal, finding that the issue should be considered under the standard for determining subject matter jurisdiction. Under that standard, the court found that claims for breach of fiduciary duty and negligence were not precluded by SLUSA because defendants’ failure to abide by generally accepted accounting principles or to conduct proper due diligence did not necessarily involve misrepresentations. Id. at *8-10, *14-17. Because the negligent misrepresentation and fraud claims, however, “necessarily turn[ed] on some false conduct,” the court found that those claims were precluded by SLUSA. Id. at *9-10, *18. As in the Meridian Capital case, the court also considered whether groups of lawsuits consolidated by a MDL Panel could be considered a “covered class action” and found that even cases that were not deliberately brought collectively, but instead were consolidated through an MDL, could be precluded by SLUSA. Id. at *13-14. The court subsequently granted the defendants’ motion for reconsideration in part, dismissing certain allegations predicated on false conduct supporting breach of fiduciary duty claims, noting that there were still surviving due diligence claims independent of any duty to disclose investment risk. No. 09 Civ. 118 (VM), 2015 WL 9450503, at *1-2 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 28, 2015).

In Henderson v. Bank of New York Mellon Corp., No. CV 15-10599-PBS, 2015 WL 7432329, at *1 (D. Mass. Nov. 23, 2015), the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts considered a claim brought by an income beneficiary of a trust against a trustee for investing trust assets “almost exclusively in proprietary mutual funds … [for its] own financial benefit rather than the best interests of the trust beneficiaries.” Noting that “[a]fter Troice, a mere coincidence of fraud with a transaction in covered securities will no longer suffice for SLUSA preemption,” the court found that, because the alleged “fraud was not in connection with the purchase or sale of the covered securities except by the fraudster, i.e. the trustee,” the claim was not preempted by SLUSA. Id. at *3-4. The defendant has moved the court to certify for interlocutory appeal. No. CV 15-10599-PBS (D. Mass. Dec. 23, 2015).

In Lim v. Charles Schwab & Co., Inc., No. 15-CV-02074-RS, 2015 WL 7996475, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 7, 2015), the United States District Court for the Northern District of California analyzed claims brought by investors against their retail broker, Charles Schwab, and UBS. The complaints alleged that Schwab, who promised its investors to provide the “best execution” for their trades, violated that promise by routing over 95% of trades to UBS. Id. at *2. The court found that the misrepresentation prong of SLUSA was satisfied because by failing to deliver services it had promised, Schwab had either misrepresented or omitted to state that best execution would not occur. Id. at *6. The court found that the “in connection with” element was also satisfied because Schwab’s false promise was “(1) directed at Schwab’s clients (2) in order to induce them to purchase or sell securities through Schwab for a fee, and (3) caused losses directly resulting from what clients believed to be legitimate securities transactions.” Id. at *7. The court likewise found claims against UBS to be precluded because UBS’s “manipulation” of prices in its “dark pool” occurred “in connection” with the purchase or sale of covered securities. Id. at *8.

Finally, since our 2015 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, the Southern District of New York and the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey reached different conclusions in considering SLUSA preclusion issues arising out of the same alleged fraudulent activity on motions to remand to state court. In May of 2009, the AXA Equitable Life Insurance Company introduced a “volatility management strategy” for certain investment accounts without properly obtaining approval from the New York State Department of Financial Services (“DFS”). Investor-plaintiffs brought separate suits in both the D.N.J. and the S.D.N.Y. In Shuster v. AXA Equitable Life Ins. Co., No. 14-8035 (RBK/JS), 2015 WL 4314378, at *7-8 (D.N.J. Jul. 14, 2015), the D.N.J. utilized the factors set forth in the Third Circuit’s pre-Troice decision Rowinski v. Salomon Smith Barney Inc., 398 F.3d 294 (3d Cir.2005), to hold that, because the defendant could not establish that the purchasers would have necessarily had to alter their investments if the strategies had been submitted for approval to the DFS, the misrepresentation lacked the requisite connection with the “purchase or sale of covered securities” necessary for SLUSA preclusion. In contrast, in Zweiman v. AXA Equitable Life Ins. Co., No. 14-CV-5012 (VSB), 2015 WL 7431191, at *7-9 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2015), the S.D.N.Y. found the same misrepresentations were “in connection with” the purchase or sale of a covered security. There the plaintiff argued that because she bought her securities before the implementation of the strategy and the misleading disclosure to DFS was not public, it could not have induced her to buy, sell or hold securities. Id. at *9. Noting that “holder claims fall within SLUSA’s parameters,” the court found that the fact that plaintiff paid a premium for certain guarantee benefits created a sufficient connection to the purchase or sale of a covered security, regardless of the temporal distance. Id. at *10. Moreover, even if plaintiff was not aware of the misrepresentation, because “[a]bsent DFS approval, AXA would not have been legally permitted to introduce the ATM strategy to Plaintiff’s variable annuity policy,” the court found that defendant’s misrepresentations to the DFS were sufficiently connected to the purchase or sale of a covered security to warrant SLUSA preclusion. Id. at *11-12. The decision on the motion to remand is currently on appeal to the Second Circuit.

Print

Print