Jim Bessen is Lecturer at the Boston University School of Law. This post is based on a discussion paper authored by Professor Bessen.

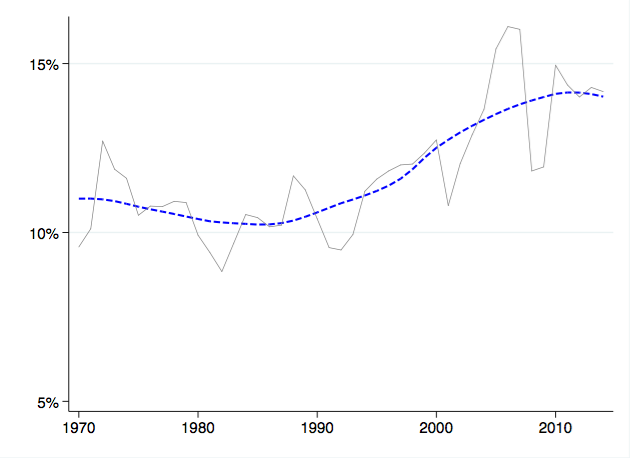

Profits are up. Operating margins for firms publicly listed in the US show a substantial and sustained rise (see Figure below). Corporate valuations are up as well. That is good news for managers and investors. But is it good news for society?

Economists, such as Joseph Stiglitz and Luigi Zingales, find the rise potentially troubling for two reasons. First, higher profits create greater economic inequality. Rising aggregate profits correspond to a decline in labor’s share of output, contributing to stagnant wages. Also, greater profits for some corporations but not others may create greater wage inequality (see “Corporate Inequality Is the Defining Fact of Business Today”).

Aggregate Operating Profits/Sales for firms publicly listed in the US

Second, the rise in profits might represent a decline in competition and, with that, a decline in economic dynamism. While a dynamic, competitive economy rewards innovative firms with high profits and punishes poor performers with low profits, sustained aggregate profits suggest, instead, that firms are able to get away with higher prices because competition is limited. Firms engage in political “rent seeking”—lobbying for regulations that provide them sheltered markets—rather than competing on innovation. If so, then high profits portend diminished productivity growth.

But there is a more optimistic narrative about the rise of profits. Perhaps profits are rising because firms are increasingly making profitable investments in new technology, in IT, or in their organizational capabilities. In this account, high profits represent increased economic dynamism.

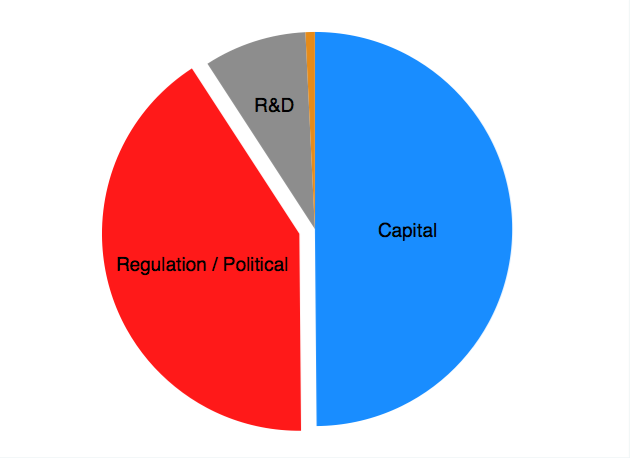

So which is it, political rent seeking or cutting edge investments? In a new research paper, I tease apart the factors associated with the growth in corporate valuations relative to assets (Tobin’s Q) and the growth in operating margins. Beyond investment in conventional assets, I account for the roles of R&D, spending on advertising and marketing, and IT/“organizational capital”; I also consider investments in lobbying, political campaign spending, and regulation; and I look for links between rising profits and industry concentration and stock volatility.

I find that investments in conventional capital assets and R&D account for a substantial part of the rise in valuations and profits especially during the 1990s. However, since 2000, political activity and regulation account for a surprisingly large share of the increase.

Contribution to Rise in Operating Margins, 1971-2014, US public firms

Regulation and Profits

Much of this result is driven by the role of regulation, so it is important to understand the link between regulation and profits. It is obvious that lobbying and political campaign spending might result in favorable regulatory changes. Several studies find the returns to these investments can be quite large. For example, one study finds that for each dollar spent lobbying for a tax break, firms received returns in excess of $220.

It is less obvious, however, that regulation in general should be associated with higher profits. Indeed, critics of the regulatory state regularly decry the costs imposed by regulations. Yet even such costs might raise profits; for example, one study found that pollution regulations served to reduce entry of new firms into some manufacturing industries; costs to incumbents are also entry barriers to prospective entrants.

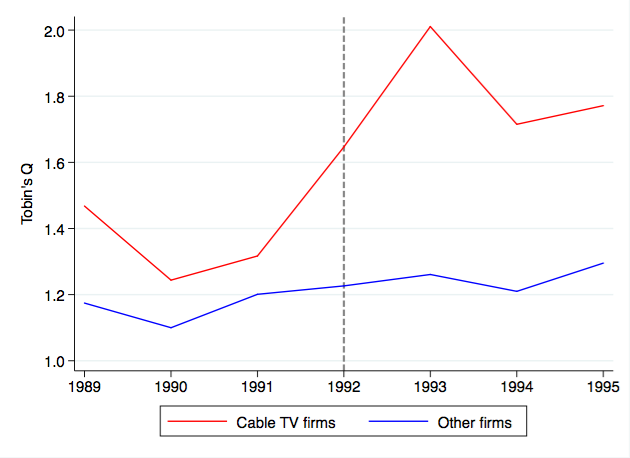

Even when regulators try to reduce prices, firms can benefit. For example, in 1992 Congress passed the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act in response to high cable TV rates. Regulators expected cable prices to fall by 10%. Instead, however, cable companies changed their programming bundles, prices did not fall, and corporate valuations increased. Figure 3 shows that the aggregate market value of cable companies relative to assets (Tobin’s Q) rose following the Act, compared to valuations of other firms.

Rise in Corporate Valuations / Assets around 1992 Cable Act;

7 Cable TV firms and 2,137 other firms

The complexity of regulation and the rent seeking activities that firms undertake to benefit from regulation provide ample opportunity for regulation to bring higher profits. I find that the pattern around the 1992 Cable Act is representative: firms experiencing major regulatory change see their valuations rise 12% compared to closely matched control groups. Smaller regulatory changes are also associated with a subsequent rise in firm market values and profits.

Troubling Profits

This research supports the view that political rent seeking is responsible for a significant portion of the rise in profits. Firms influence the legislative and regulatory process and they engage in a wide range of activity to profit from regulatory changes, to significant success. Without further research, we cannot say for sure whether this activity is making the economy less dynamic and more unequal, but the magnitude of this effect certainly heightens those concerns.

Two characteristics make these changes particularly worrisome. First, the link between regulation and profits is highly concentrated in a small number of politically influential industries. Among non-financial corporations, most of the effect is accounted for by just five industries: pharmaceuticals/chemicals, petroleum refining, transportation equipment/defense, utilities, and communications. These industries comprise, in effect, a “rent seeking sector.” Concentration of political influence among a narrow group of firms means that those firms may skew policy for the entire economy. For example, the pharmaceutical industry has actively stymied efforts to address problems of patent trolls that affect many other industries.

Second, while political rent seeking is nothing new, the outsize effect of political rent seeking on profits and firm values is a recent development, largely occurring since 2000. Over the last 15 years, political campaign spending by firm PACs has increased by more than thirty-fold and the Regdata index of regulation has increased by nearly 50% for public firms. However much political rent seeking has affected economic dynamism and inequality so far, the effect is likely to be greater in the near future.

The full paper is available for download here.

Print

Print