Monica K. Loseman is a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. This post is based on a Gibson Dunn publication by Ms. Loseman, Jonathan C. Dickey, and Mark A. Perry and is part of the Delaware law series; links to other posts in the series are available here.

The first half of 2016 yielded several important developments in securities litigation, including federal appellate decisions applying Omnicare and Halliburton II, as well as Delaware court opinions regarding the application of collateral estoppel to parallel cases previously dismissed based on demand futility, a price-increase for dissenting stockholders in a management-led buyout, and yet further developments on disclosure-only settlements. This post highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the first half of 2016:

- We highlight the Second Circuit’s opinion in Tongue v. Sanofi, which offers the most extensive appellate analysis of Omnicare to date.

- In a similar vein, we analyze post-Halliburton II opinions, including the Eighth Circuit’s decertification of a class of Best Buy stockholders. We also highlight significant cases pending in the Second Circuit and notable district court opinions.

- A recent Sixth Circuit decision has deepened the circuit split over whether the American Pipe class action tolling doctrine of applies to statutes of repose for claims under the Securities Act.

- A pending petition for certiorari asks the U.S. Supreme Court to determine whether a privately held corporation trading in its own stock has an Exchange Act duty to disclose all material information to potential sellers or else refrain from trading.

- We also highlight important developments in Delaware courts, including the Chancery Court twice applying collateral estoppel to bar relitigation of parallel cases dismissed based on demand futility.

- The Chancery Court also awarded a 28% price increase to stockholders who dissented from the 2013 management-led buyout of Dell, Inc.

- The Delaware Supreme Court upheld the Zales-Signet merger, confirming in the process that a fully informed, uncoerced vote of disinterested stockholders will generally serve to shield directors and advisors from post-closing damages claims.

- The Chancery Court also approved a disclosure-only settlement, demonstrating that the door to such settlements is not entirely closed post-Trulia.

We highlight these and other notable developments in securities litigation in our post below.

Filing and Settlement Trends

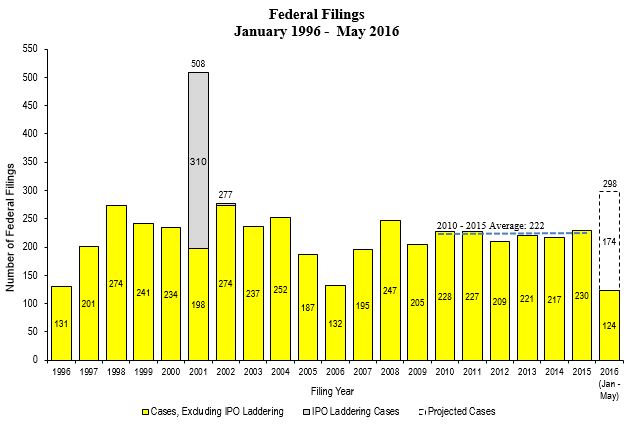

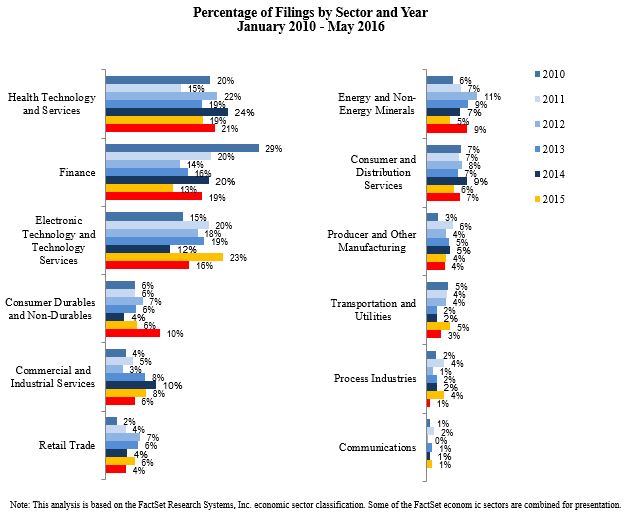

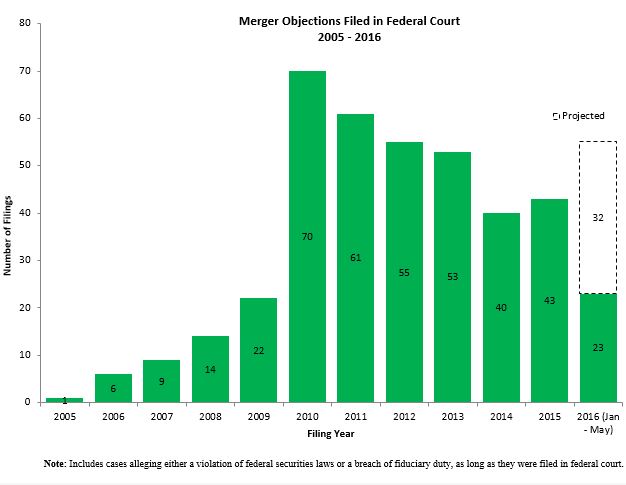

Through the first five months of 2016, new securities class actions are on pace to exceed the annual filing rates of every year in the last two decades (except for 2001, when several hundred so-called “IPO laddering cases” were filed). According to a newly-released study by NERA Economic Consulting (“NERA”), 298 class actions are projected to be filed in 2016, compared to the five year average of 222 cases. The industry sectors most frequently sued in 2016 have been healthcare (21% of all cases filed), finance (19%), and tech (16%). Of these three sectors, cases filed against tech companies actually dropped significantly year-over-year, from 23% of cases down to 16%. NERA also projects that the number of “merger objection” cases filed in federal court in 2016 will be significantly greater than 2015, and will represent approximately 18% of all securities cases filed in the federal courts in 2016.

With respect to settlement trends, median settlements in the first half of 2016 are up slightly from 2015, while average settlement amounts also increased slightly. A wide range of cases, both big and small, comprised the population of settled cases: over 50% of settlements in the first half of 2016 were under $10 million, while roughly 20% were over $50 million. Most significantly, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses continue to reflect a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last fifteen years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded about 3% of total alleged investor losses, and the percentage has dropped each year for the last three years. In the first half of 2016, the percentage declined once again to 1.4%.

Filing Trends

Overall filing rates for the first half of 2016 are reflected in Figure 1 below (all charts courtesy of NERA). One hundred twenty-four cases have been filed so far this year, annualizing to 298 cases. This figure does not include the many class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Those state court cases, however, represent a “force multiplier” of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation in the United States today.

Figure 1:

Mix of Cases Filed in First Half of 2016

Filings By Industry Sector

New case filings in the first half of 2016 reflect an increase in the percentage of cases filed against healthcare and finance companies, while the percentage of cases filed against tech companies declined. The biggest percentage increases in new case filings in the first half of 2016 were against companies in the consumer goods and energy sectors. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3 below, 23 “merger objection” cases were filed in federal court in the first half of 2016, which annualizes to 55 cases for the year. This would be a significant increase over 2015. Note, also, that this statistic only tracks cases filed in federal courts. The real action in M&A litigation is in state court, particular the Delaware Chancery Court. But as discussed below in our discussion of “Delaware/Derivative Litigation Developments,” the Delaware Court of Chancery recently announced that the much-abused practice of filing an M&A case followed shortly by an agreement on “disclosure only” settlement is just about at an end, and with it, we anticipate a decline in the total number of M&A suits filed in the Chancery Court.

Figure 3:

Settlement Trends

As Figure 4 shows, median settlements were $7.8 million in the first half of 2016, slightly higher than full year 2015, but still much lower than median amounts in nearly the last dozen years. One can speculate about what may account for the up-and-down trend in median settlements in the last few years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act or Section 11 of the Securities Act. Median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of one or more large settlements, any one of which can skew the numbers. In the first half of 2016, for example, the number of settlements above $100 million increased from 13% to 17% of all settlements. At the same time, the number of settlements below $10 million remained flat.

Figure 4:

Perhaps all that can be said of overall settlement trends is that plaintiffs’ lawyers continue to thrive. According to NERA, total attorneys’ fee awards in 2015 were in excess of $1 billion, representing a big increase from 2014’s total of $672 million. These astronomical amounts have become the “new normal,” as total fees over the last decade have ranged from a low of $671 million to a high of $1.7 billion, with the amounts in seven out of ten years exceeding $1 billion.

Omnicare: The Second Circuit Weighs In

As we described in our 2015 Mid-Year and Year-End Securities Litigation Updates, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015), has had a significant impact on cases brought under the federal securities laws. The effects were felt first in the district courts, and now appellate courts have begun to join in. We focus below on Tongue v. Sanofi, 816 F.3d 199 (2d Cir. 2016), the Second Circuit’s first published opinion interpreting Omnicare and the most extensive appellate analysis of Omnicare to date.

In Omnicare, the Supreme Court resolved a circuit split regarding the scope of liability for false statements of opinion under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933. Section 11 imposes liability where a registration statement “[1] contained an untrue statement of a material fact or [2] omitted to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading.” 15 U.S.C. § 77k(a). The Court decided in Omnicare that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an untrue statement of material fact, regardless of whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong.” 135 S. Ct. at 1327 (quotation omitted). The Court also held that an omission makes an opinion statement actionable where the omitted facts “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take away from the opinion itself.” Id. at 1329. In other words, an opinion statement becomes misleading “if the real facts are otherwise, but not provided.” Id. at 1328.

District courts have wrestled with Omnicare‘s holdings. Despite predictions that Omnicare might make it easier for plaintiffs to bring Section 11 claims against issuers, the early decisions have been mixed. For example, in Federal Housing Finance Agency v. Nomura Holding America, Inc., 104 F. Supp. 3d 441 (S.D.N.Y. 2015), the court found that an alleged omission was actionable because a defendant’s statement about its belief “implied that defendants knew facts sufficient to justify forming the opinion [it] expressed” but the record contained “evidence that [defendant] lacked the basis for making those statements that a reasonable investor would expect.” Id. at 555-56 (quotations omitted). The FHFA decision is currently under appeal to the Second Circuit. Plaintiffs did not fare as well in Medina v. Tremor Video, Inc., No. 13-cv-8364, 2015 WL 3540809 (S.D.N.Y. June 5, 2015). In this case, the court found that “[d]efendants’ registration statement contained hedges, disclaimers, and qualifications addressing the risks associated with each statement of opinion used, specifically cautioning investors.” Id. at *2 (quotation omitted). Accordingly, there was no actionable misrepresentation. The Second Circuit agreed on February 8, 2016, in a non-precedential summary order, holding that the complaint did not adequately allege that defendants knew of additional material that should have been, but was not, disclosed. Medina v. Tremor Video, Inc., No. 15-2178-CV, 2016 WL 482160, at *2 (2d Cir. Feb. 8, 2016). [1]

On March 4, 2016, the Second Circuit issued its opinion in Tongue v. Sanofi, its first published decision interpreting Omnicare. The defendant, a global pharmaceuticals company, had allegedly violated federal and state securities laws by failing to disclose material information about its drug Lemtrada, which is used to treat multiple sclerosis. Specifically, the plaintiffs alleged that Sanofi had made multiple public statements about the high likelihood that Lemtrada would be approved by the FDA and the short timeline for the expected approval. Sanofi allegedly did not disclose that the FDA stated on multiple occasions that it was concerned about Sanofi’s use of so-called “single-blind” drug trials for Lemtrada instead of more widely accepted “double-blind” trials. Sanofi did not obtain FDA approval for Lemtrada on the expected timeline, but the drug was ultimately approved a short time later.

In the district court, Sanofi and the other defendants moved to dismiss on the grounds that the alleged misrepresentations were statements of opinion, and there was no showing that defendants did not genuinely believe those opinions or that the statements were objectively false. Plaintiffs argued in response that Sanofi’s disclosures omitted facts about the FDA’s feedback on “single-blind” trials and that feedback was necessary to make Sanofi’s optimistic statements about FDA approval not misleading. The district court agreed with defendants, dismissed the federal claims, and refused to exercise discretionary jurisdiction over the state claims.

The Second Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision, agreeing with both its “reasoning and holding.” Sanofi, 816 F.3d at 203. However, because the district court had decided the case before Omnicare was issued, the Second Circuit took the opportunity to engage in a lengthy analysis of the Supreme Court’s decision.

The Second Circuit held in Sanofi that the principal effect of Omnicare was to modify Fait v. Regions Financial Corp., 655 F.3d 105 (2d Cir. 2011), which had held that an opinion was actionable only if it was both “objectively false and disbelieved by the defendant at the time it was expressed.” Sanofi, 816 F.3d at 209-10 (emphasis added). In Sanofi, the Second Circuit ruled that under Omnicare, only one of these two predicates—i.e., “the speaker did not hold the belief she professed” or “the supporting fact she supplied [for the opinion] w[as] untrue”—was required. Id. (quotations and citations omitted).

Sanofi may indicate that the Second Circuit is taking a narrow view of what factual statements and omissions will be actionable under Omnicare. Although the FDA had warned Sanofi that approval of Lemtrada would be difficult without the use of double-blind trials, Sanofi did not disclose these warnings. It publicly opined that it was confident in the FDA’s approval of Lemtrada and that it was 90% probable that Lemtrada would be approved on the expected timeline. The Second Circuit found that Sanofi’s failure to disclose the warnings was immaterial even in the context of Sanofi’s “exceptional optimism.” 816 F.3d at 211. In doing so, the court of appeals placed great weight on the principle that “an issuer is not liable [for a statement of opinion] merely because it ‘knows, but fails to disclose some fact cutting the other way.'” Id. at 214 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329). The FDA warnings here were simply facts that “would have potentially undermined Defendants’ optimistic projections.” Id. at 212. “Omnicare does not impose liability merely because an issuer failed to disclose information that ran counter to an opinion expressed in the registration statement.” Id. at 213.

Significantly, the Second Circuit also relied on the sophistication of securities investors in denying the class plaintiffs’ claims. According to the Circuit, the FDA’s partiality towards double-blind trials was well known, and “[s]ophisticated investors, aware of the FDA’s strong preference for double-blind trials, cannot claim surprise when it is revealed that the FDA meant what it said.” Id. at 212-13. The plaintiffs were also charged with the knowledge that Sanofi was involved in a “continuous dialogue” with the FDA concerning Lemtrada, which would necessarily include “the sufficiency of various aspects of the clinical trials,” and that Sanofi’s projections “[we]re synthesized from a wide variety of information,” including this dialogue. Id. at 211-12.

Other circuits will weigh in on Omnicare during the coming months, and we will continue to monitor their progress. In particular, we expect that future decisions will address whether to extend Omnicare‘s holdings to other provisions of the Exchange and Securities Acts, continuing a trend from the Tenth Circuit’s decision in Nakkhumpun v. Taylor, 782 F.3d 1142 (10th Cir. 2015), which applied Omnicare to Section 10(b). At this point, however, Sanofirepresents the most extensive explication of Omnicare from any court of appeals.

Standard for Establishing Price Impact After Halliburton II

In the two years since the Supreme Court held that defendants could rebut the presumption of reliance established in Basic v. Levinson (the “Basic presumption”) at the class certification stage in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. (“Halliburton II“), courts have grappled with the implications of that decision. Recently, we have seen increased focus on three unresolved questions. First, what evidence is sufficient to rebut the Basic presumption? Second, beyond expert evidence that a price movement was not statistically significant, what evidence is appropriate for consideration at the class certification stage? And finally, when defendants present evidence rebutting the Basic presumption, does the burden of persuasion then shift to the plaintiffs to show that the alleged misrepresentations did, in fact, impact the stock price? In the past six months, district court decisions generally have continued to favor certification, but cases are beginning to reach the appellate courts, and a decision by the Eighth Circuit to decertify a class of Best Buy stockholders sets a different tone.

Eighth Circuit Reverses Class Certification in Best Buy Case

In April, the Eighth Circuit addressed whether a defendant had produced evidence sufficient to rebut the Basic presumption of reliance. As we discussed in our April 15, 2016 client alert, the Eighth Circuit reversed class certification in IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., holding that the district court “misapplied the price analysis mandated by Halliburton II.” 818 F.3d 775, 777 (8th Cir. 2016). In Best Buy, plaintiffs moved to certify a class based on two purportedly misleading statements made during a post-market-opening conference call, which the parties agreed were “virtually the same” as non-actionable pre-market-opening statements. Id. at 778, 782. The district court certified the class, despite plaintiffs’ expert’s opinion that the conference call statements caused no price movement on the day they were made beyond that already caused by the earlier, dismissed statements. Id. at 782. In ruling that the district court had abused its discretion in certifying the class, a majority of the Eighth Circuit panel concluded that Best Buy had presented “strong evidence”—the opinion of plaintiffs’ own expert—that the conference call statements’ lack of impact on the price of Best Buy stock “severed any link between the alleged conference call misrepresentations and the stock price at which plaintiffs purchased.” Id. at 782–83. Because the plaintiffs did not present any contrary evidence, they failed to satisfy the predominance requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3). Id. at 783.

Best Buy has several major implications for securities fraud class actions, particularly those based on the “price maintenance” theory—specifically, that a misrepresentation is actionable if it prevents the price of the stock from dropping until a corrective disclosure. Most significantly, the Eighth Circuit reversed certification despite evidence that Best Buy’s stock price had dropped after a corrective disclosure three months after the conference call, noting that the price maintenance theory alone was insufficient to refute “defendants’ overwhelming evidence of no price impact.” Id. Further, the Eighth Circuit cited Federal Rule of Evidence 301 in discussing the parties’ relative burdens. See id. Applying Rule 301 burden shifting to the Halliburton II analysis would allow defendants to place reliance at issue by producing evidence of a lack of price impact and, thus, shift the burden of persuasion back to plaintiffs. On June 1, 2016, the Eighth Circuit denied rehearing en banc.

Halliburton Remand Set for Argument

As we discussed in our 2015 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Fifth Circuit granted Halliburton leave to appeal the district court’s class certification as to one of six alleged corrective disclosures. The merits have been fully briefed, and oral argument is currently set for the week of August 29.

The main issue before the Fifth Circuit is the propriety of the district court’s decision (on remand from the Supreme Court) that “the issue of whether disclosures are corrective is not a proper inquiry at the certification stage,” as the court would otherwise be required to conduct a premature inquiry into the merits of the action. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 309 F.R.D. 251, 261–62 (N.D. Tex. 2015) (citing Halliburton II, 134 S.Ct. at 2416). Halliburton has argued that Halliburton II permits class certification only after full consideration of all price-impact evidence. And, where plaintiffs’ only evidence that the alleged misstatements had a price impact is a subsequent price drop, the court must consider whether the price drop is associated with negative company news that actually corrects the alleged misstatement. Brief of Appellant at 27-28, Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., No. 15-11096 (5th Cir. Feb. 8, 2016).

Even if the determination of whether a disclosure was corrective is highly relevant to the merits of the case, price impact is fundamental to evaluating the predominance requirement of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(b)(3), and thus the corrective disclosure must be evaluated by the court at the certification stage. Id. at 36; see also Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 133 S.Ct. 1426, 1432 (2013) (noting that the Court’s precedents “requir[e] a determination that Rule 23 is satisfied, even when that requires inquiry into the merits of the claim”). Otherwise, as the plaintiffs’ argument suggests, price impact could be shown by any price drop on a day when negative information was announced about a defendant so long as the announcement followed an alleged misstatement, regardless of any connection between the alleged misstatement and the subsequent announcement, leading to absurd results. Reply Brief of Appellant at 1, Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., No. 15-11096 (5th Cir. Apr. 21, 2016).

Should Halliburton prevail, the Fifth Circuit will be the first to affirmatively hold that if an alleged disclosure is not corrective of an alleged misrepresentation, it cannot be evidence of price impact. Further, Halliburton has argued that on remand, FRE 301 and Basic require the plaintiffs to bear the burden of persuasion once the defendants have produced evidence demonstrating a lack of price impact. See Brief of Appellant at 52–60.

Second Circuit Arguments to Watch

Two notable appeals are pending in the Second Circuit. First, on January 26, 2016, the Second Circuit granted leave to appeal from a decision certifying a class in In re Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. Sec. Litig., 2015 WL 5613150. The defendants have asked the Second Circuit to review, among other things, whether the district court created a “virtually insurmountable legal standard” by ruling that to rebut the Basic presumption, defendants must “demonstrate a complete absence of price impact” with “conclusive evidence.” Brief of Appellant at 24, Ark. Teachers Retirement Sys. v. Goldman Sachs, Inc. et al., No. 16-250 (2d Cir. Apr. 27, 2016). Further, the defendants also argue that the district court erred in refusing to consider “unrebutted evidence that (a) Goldman Sachs’ stock price did not increase when the challenged statements were made, and (b) the information alleged by Plaintiffs to be corrective … was both already disclosed … and caused no statistically significant price reaction on the earlier disclosure dates” simply because this evidence also bore on the ultimate determination of materiality. Id. at 25.

In addition, the Second Circuit recently granted leave to appeal certification of a class in Strougo v. Barclays PLC, 312 F.R.D. 307. In their motion for leave to appeal, the defendants argued that the district court improperly placed the burden on them to prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the price of Barclays’ American Depositary Shares could not have been impacted by the alleged misstatements. Defs.’ Pet. for Permission to Appeal Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f) at 10–11, Strougo v. Barclays PLC, No. 16-450 (2d Cir. Feb. 16, 2016). The defendants further argued that the district court entirely failed to consider evidence that there was no statistically significant impact on the stock price at the time of the alleged misstatements, instead concluding that because plaintiffs had “asserted a tenable theory of price maintenance” by demonstrating a price drop on the date of a corrective disclosure, defendants’ evidence had not “foreclose[d] plaintiffs’ reliance on the price maintenance theory.” Id. at 10–12. These two cases should prompt the Second Circuit to reach conclusions regarding the burden of proof and price maintenance evidence, either joining the Eighth Circuit or, potentially, creating a split in the circuits.

Notable District Court Opinions

District courts have continued to issue opinions applying Halliburton over the last six months, mostly favoring certification. Most arguments are similar to those that have begun percolating up to the appellate courts. For example, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee concluded that the defendants had failed to rebut the Basic presumption by only producing evidence of a lack of price impact at the time of the alleged misstatements. See Burges v. Bancorpsouth, Inc., No. 3-14-1564, 2016 WL1701956, at *3 (M.D. Ten. Apr. 28, 2016). In their motion for leave to appeal to the Sixth Circuit, defendants argue that the court erred in that holding, and in failing to consider unrebutted evidence that the market showed no interest in the alleged misstatements, found in SEC filings but “not reviewed or commented on by analysts or other significant market participants.” Defs.’ Pet. for Permission to Appeal Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f) at 17, Burges v. Bancorpsouth, Inc., No. 16-505 (6th Cir. May 12, 2016) (emphasis in original). The defendants in Burges further urge the Sixth Circuit to rule that FRE 301 requires the burden of persuasion to remain with the plaintiffs once evidence rebutting the Basic presumption is produced. Id. at 19. Likewise, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California rejected defendants’ similar attempts to show a lack of price impact for the majority of alleged misstatements by only analyzing “front-end” price impact where there was no dispute that the stock price dropped on all of the alleged corrective disclosure dates. See Hatamian v. Advanced Micro Devices, Inc., No 14-cv-00226, 2016 WL 1042502 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 16, 2016). The court there declined to address the issue of whether FRE 301 applies. Id. at *7 n.5.

* * *

We will continue to monitor developments in all courts throughout the remainder of the year.

Sixth Circuit Weighs in on Circuit Split Concerning American Pipe Tolling Question, Follows Second Circuit Opinion in IndyMac

As we described in our 2014 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the U.S. Supreme Court has left unresolved whether the class action tolling doctrine of American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974), applies to statutes of repose for claims under the Securities Act of 1933. Circuits have split over the question, with the Second Circuit holding that the filing of a class action does not toll the 1933 Act’s statute of repose, rendering belated individual claims untimely. Police & Fire Ret. Sys. v. IndyMac MBS, Inc., 721 F.3d 95, 106-09 (2d Cir. 2013). The Tenth Circuit, in contrast, concluded that American Pipe applies to the Securities Act statute of repose. Joseph v. Wiles, 223 F.3d 1155, 1166-68 (10th Cir. 2000).

Siding with the Second Circuit, the Sixth Circuit in May ruled that the tolling doctrine established by American Pipe does not apply to the three-year statute of repose governing claims under the Securities Act of 1933 or to the five-year statute of repose governing claims under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. In Stein v. Regions Morgan Keegan Select High Income Fund, Inc., Nos. 15-5903, 15-905, 2016 WL 2909333 (6th Cir. May 19, 2016), plaintiffs alleged that defendants had violated Sections 11, 12(a)(2), and 15 of the Securities Act and Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Exchange Act by misrepresenting risks related to certain investment funds. The Sixth Circuit held that plaintiffs’ claims were time-barred by the statutes of repose contained in the Securities Act and the Exchange Act. The court’s holding hinged on the distinction between a statute of limitations, which creates a time limit for filing a civil claim that ordinarily commences when the claim accrues (usually when injured or when the plaintiff discovers the injury), and a statute of repose, which creates a time limit for filing a civil claim that ordinarily commences when the defendant commits its last culpable act or omission, and that functions as a substantive outer limit on the period within which the plaintiff may sue.

The Sixth Circuit’s decision in Stein deepens the split among the federal courts of appeals. However, Stein is the first circuit court decision to consider the issue after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in CTS Corp. v. Waldburger, 134 S. Ct. 2175 (2014), which explored the distinction between statutes of limitations and statutes of repose in a different context. Although CTS concerned preemption of a state statute of repose and therefore at least arguably is not directly applicable to the question presented in Stein, the Supreme Court emphasized that statutes of repose “effect a legislative judgment that a defendant should ‘be free from liability after the legislatively determined period of time'” and are “in essence an ‘absolute bar’ on a defendant’s temporal liability.” CTS, 134 S. Ct. at 2183 (alteration and citations omitted). The Sixth Circuit concluded that the CTS principle supports the view that statutes of repose affect substantive rights for purposes of the Rules Enabling Act, and therefore cannot be altered by a doctrine founded on a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure.

The Third Circuit is also poised to weigh in on the applicability of American Pipe tolling to statutes of repose. In North Sound Capital LLC v. Merck & Co., the District of New Jersey held that American Pipe tolling applied to the statute of repose for Exchange Act claims by a group of plaintiffs who were class members in a suit filed in 2008 but who then opted out in 2013. North Sound Capital LLC v. Merck & Co., Nos. 3:13-cv-7240 (FLW), 3:14-cv-7241 (FLW), 3:13-cv-242 (FLW), 3:14-cv-241 (FLW), 2015 WL 5055769, at *11 (D.N.J. Aug. 26, 2015). The district court certified the issue for interlocutory appeal and briefing in the Third Circuit is now complete.

Federal Securities Laws and Unicorns

“Unicorns”—private companies valued at or above $1 billion—are in the securities spotlight in 2016. On March 31, SEC Chair Mary Jo White focused her keynote address at the SEC-Rock Center Silicon Valley Initiative on the disclosure obligations of large private companies, citing the increasing number of unicorns and unicorn financings. Chair White cautioned such companies about the perils of disregarding investor interests, noting that “being a private company comes with serious obligations to investors and the markets. Whether the source of the obligation is the federal securities laws or the fiduciary duty that is owed to shareholders, the resulting candor and fair dealing should be fundamentally the same.” Mary Jo White, Chair, Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, Keynote Address at the SEC-Rock Center on Corporate Governance Silicon Valley Initiative (March 31, 2016), available at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/chair-white-silicon-valley-initiative-3-31-16.html (and discussed on the Forum here).

On the litigation front, the plaintiff in Fried v. Stiefel Labs., Inc. is now asking the U.S. Supreme Court to define and expand the scope of those legal and fiduciary obligations by determining whether a privately held corporation purchasing its own stock has an Exchange Act duty to disclose all material information to potential sellers or else refrain from trading with those sellers. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Fried v. Stiefel Labs., Inc., 2016 WL 3136684 (2016) (No. 15-1458).

Plaintiff Richard Fried is a former CFO of Stiefel Laboratories, Inc. (“SLI”) who sold his shares in the then-private company back to SLI in January 2009 for roughly $16,500 a share—shortly before GlaxoSmithKline LLC agreed to buy SLI for approximately $70,000 per share in April 2009. Fried sued SLI and its President, Charles Stiefel, for, among other things, securities fraud under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 because SLI purchased Fried’s stock without disclosing that the company was in negotiations for a potential sale.

At trial, Fried asked the court to incorporate into a pattern jury instruction for a Rule 10b-5(b) claim the statement “Defendants had a duty to disclose all material information to Mr. Fried.” Fried v. Stiefel Labs., Inc., 814 F.3d 1288, 1292 (11th Cir. 2016). The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida refused and the Eleventh Circuit affirmed, holding that Rule 10b-5(b) only prohibits omissions necessary to prevent previous affirmative representations from becoming misleading: “An insider who makes no affirmative misrepresentation but trades on nonpublic information may violate Rule 10b-5(a) or (c), but not rule 10b-5(b).” Id. at 1294-95.

On May 31, 2016, Fried petitioned the Supreme Court for review, asserting that the Eleventh Circuit decision created a circuit split. According to Fried, “the Eleventh Circuit’s strict insistence that a claim resting on this relationship-based duty to disclose must proceed under subsection (a) or (c) of Rule 10b-5 and satisfy the elements of a classical insider trading claims … and cannot proceed as a typical omission-based securities fraud claim [under Rule 10b-5(b)], conflicts with the Second, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits’ less formalistic approach to § 10(b) and Rule 10b-5.” Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Fried v. Stiefel, 2016 WL 3136684 at *3.

As noted in our previous updates, the Supreme Court has been actively taking up important securities laws issues in recent terms. Accordingly, and in light of the SEC’s recent focus on large private companies and their transition to public ownership, there is an increased likelihood that the Court will take the opportunity to further define this important area of law. For unicorns such as Snapchat, Pinterest, and Intarcia Therapeutics, as well as the many private companies that aspire to be, this issue deserves particular attention.

Delaware/Derivative Litigation Developments

In the past six months, the Delaware Court of Chancery and Delaware Supreme Court have had occasion to expand upon several seminal rulings, in the areas of claim preclusion for stockholder derivative actions, appraisal actions, challenges to mergers, and disclosure-only settlements. These opinions apply and give meaning to the broad principles articulated in prior rulings, and should be of interest to counsel and companies alike.

Following Pyott, Delaware Chancery Court Twice Applies Collateral Estoppel to Prior Judgments of Demand Futility

In developments that are significant for defendants faced with parallel actions across multiple jurisdictions, two recent Court of Chancery decisions applied and expanded upon the Delaware Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Pyott v. LAMPERS, 74 A.3d 612, 618 (Del. 2013) to hold that a federal stockholder derivative plaintiff’s election not to use books and procedures under Delaware law (a “Section 220” action) did not bar the application of preclusion doctrines in subsequent derivative suits.

As background, the Delaware Supreme Court in Pyott rejected a “‘fast filer’ irrebuttable presumption” of inadequate representation, which would have allowed stockholder derivative plaintiffs to circumvent the preclusive effect of a demand futility ruling rendered in virtually any parallel case in which the first derivative plaintiff opted not to use the books and records tools available under Section 220. The arguments for the presumption had been based on the notion that quick-filing plaintiffs who seek to plead demand futility without the benefit of books and records must be motivated by their own desire to control derivative litigation, rather than a desire to do what is best for the corporation. The Delaware Supreme Court recognized these concerns, but rejected a bright-line presumption of inadequacy.

Two notable recent cases have followed Pyott. First, in May 2016, Chancellor Bouchard dismissed a derivative action on the basis that a prior Rule 23.1 dismissal rendered in a parallel Arkansas federal action collaterally estopped the plaintiffs from asserting demand futility in Delaware. In re Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Deriv. Litig., 2016 WL 2908344 (Del. Ch. May 13, 2016). The Delaware plaintiffs argued that the federal plaintiffs were inadequate representatives—and thus collateral estoppel should not apply to bar relitigation of the issue of demand futility—because the federal plaintiffs’ decision not to pursue books and records evidenced either a conflict of interest or grossly deficient representation of such magnitude as to violate due process. Id. at *18-20.

Referencing Pyott and Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 42, Chancellor Bouchard stated that the failure to file a Section 220 action “could serve as meaningful evidence of inadequate representation in some cases,” but cautioned that “it does not follow that plaintiffs are necessarily inadequate representatives because their counsel chose not to follow a recommended strategy in a different action,” even if that strategy had been recommended by leading jurists of the Delaware courts. Id. at *20.

Chancellor Bouchard then rejected the Delaware plaintiffs’ argument that the federal plaintiffs were inadequate because the Delaware complaint pleaded more or different facts garnered from a Section 220 action. The court noted that while it might have been “advantageous for the [federal] plaintiffs to seek additional factual support through a books-and-records action,” the federal plaintiffs still had access to many of the core documents and publicly available articles that formed the basis of the Delaware complaint, and the claims and legal theories were, at bottom, the same. Id. at *21-22. Thus, the court held, the federal plaintiffs’ decision not “to use ‘the tools at hand’ to investigate their claims” through a books and records action at most “[fell] into the category of an imperfect legal strategy and does not rise to the level of litigation management that was so grossly deficient as to render them inadequate representatives.” Id. at *21.

One month later, Chancellor Bouchard dismissed another shareholder derivative action on similar grounds. See Laborers’ Dist. Council Constr. Indus. Pension Fund v. Bensoussan, 2016 WL 3407708 (Del. Ch. June 14, 2016). Stockholder plaintiffs filed a derivative complaint in Delaware in July 2015 after completing a books and records action, and more than a year after a New York federal court had dismissed a nearly identical federal derivative complaint—filed without the benefit of books and records—for failure to adequately plead demand futility. Id. at *1. Chancellor Bouchard again rejected the argument that the federal plaintiffs’ counsel were inexperienced, and found there was a “lack of a substantive difference in the key factual allegations” and claims presented in the federal and Delaware complaints. Id. at *12. Chancellor Bouchard thus concluded that the federal plaintiffs’ failure to seek books and records was another “imperfect legal strategy” rather than representation so deficient as to bar application of collateral estoppel or res judicata. Id. at *12 & n.70 (citing Wal-Mart, 2016 WL 2908344, at *22).

Court of Chancery Awards 28% Price Increase to Stockholders Who Dissented from 2013 Management-Led Buyout of Dell Inc.

On May 31, 2016, Vice Chancellor Laster issued an important merits opinion in In re: Appraisal of Dell Inc., C.A. No. 9322-VCL, where he appraised Dell Inc.’s fair value in a 2013 management-led buyout as $17.62 per share—approximately 28% higher than the $13.75 per share transaction price approved by Dell Inc.’s stockholders.

This decision should not be read as a rejection of judicial consideration of—or even deference to—the transaction price in appraisal proceedings. Indeed, Vice Chancellor Laster acknowledged that the Court of Chancery repeatedly “has found the deal price to be the most reliable indicator of the company’s fair value, particularly when other evidence of fair value was weak.” Id. at 50. However, the Court went to great lengths to distinguish the Dell Inc. transaction from those in which the Court of Chancery deferred to the deal price in subsequent appraisal proceedings. In the Court’s view, distinguishing factors included (i) the use of a leveraged buyout pricing model to determine the transaction price, “which had the effect in this case of undervaluing the Company”; (ii) the evidence of a “valuation gap” between the trading price of Dell Inc.’s stock and the Company’s operative reality, “driven by the market’s short-term focus”; and (iii) the lack of meaningful competition among bidders before the merger agreement was signed. Id. at 62. The Court further noted that, although Dell Inc. conducted a go-shop after the merger agreement was signed, it was not sufficient to ensure that the transaction price provided fair value because (i) the go-shop ultimately resulted in only a 2% price increase for Dell Inc.’s stockholders; (ii) Dell’s large size—approximately 25 times larger than any other “jumped” deal—made a topping bid unlikely; and (ii) Michael Dell’s superior knowledge of and unique value to the Company created information asymmetries and other potential impediments to competing bidders.

This decision has conflicting implications for the growing appraisal arbitrage trend. On one hand, the decision will probably further encourage appraisal arbitrage in the context of management-led buyouts, which are more likely to involve the circumstances the Court concluded undercut the reliability of the transaction price as an indicator of fair value. On the other hand, the decision should serve as a warning to appraisal petitioners who—as the Court recognized in its opinion—frequently submit expert testimony that the subject company is worth more than double the transaction price. The Court agreed with Dell Inc. that it was “counterintuitive and illogical—to the point of being incredible—to think that another party would not have topped [the buyout group] if the Company was actually worth” petitioners’ asserted value of $28.61. Id. at 83-84. Rather, where a transaction results from a credible process free from any fiduciary breaches, the evidence likely will not support a valuation gap of the magnitude typically proffered by petitioners in appraisal proceedings.

The decision has implications for dealmakers, as well. Given the Court’s conclusion that the use of a leveraged buyout pricing model to determine the transaction price “had the effect in this case of undervaluing the company,” boards, special committees, and their advisors faced with bids from financial sponsors should take care to consider multiple valuation methodologies and determine the fairness of the proposed transaction independent of any leveraged buyout analysis. Id. at 62. Additionally, the decision serves as a reminder that go-shops will not necessarily provide a sufficient market check to justify deference to the transaction price in a subsequent appraisal proceeding. Even though the Court noted that Dell Inc.’s go-shop was “relatively open” and “flexible,” he nonetheless concluded that other factors precluded a finding that the go-shop “in fact generated a price that persuasively established the Company’s fair value.” Id. at 88, 91.

Delaware Supreme Court Upholds Zales-Signet Merger

On May 6, 2016, the Delaware Supreme Court, sitting en banc, affirmed the Chancery Court’s dismissal of claims challenging Signet’s $690 million acquisition of Zales Corporation in Singh v. Attenborough, No. 645. The Court held that the Signet-Zales deal withstood scrutiny under the business judgment rule and affirmed dismissal of claims of breach of fiduciary duty against Zales’ former directors. In doing so, the Court reaffirmed its holding in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304 (Del. 2015), that the deferential business judgment rule—and not Revlon‘s “enhanced scrutiny” standard—applies where the transaction is approved by a fully-informed, uncoerced vote of disinterested stockholders. In those circumstances, the only claims that survive are those for “waste,” but “because the vestigial waste exception has long had little real-world relevance,” when a claim is governed by business judgment review, “dismissal is typically the result.” Id. at 2-3.

Additionally, while the Court also affirmed dismissal of the aiding and abetting claim against Zales’ financial advisor—finding it “skeptical” that the supposed wrongdoing produced a rational basis to infer scienter—it took issue with the Chancery Court’s suggestion that an advisor can only be liable if it aids and abets a non-exculpated breach of fiduciary duty. Id. at 3. Citing its holding in RBC Capital Mkts., LLC v. Jervis, 129 A.3d 816, 862 (Del. 2015) (“Rural Metro“), the Court emphasized that “an advisor whose bad-faith actions cause its board clients to breach their situational fiduciary duties (e.g., the duties Revlon imposes in a change-of-control transaction) is liable for aiding and abetting.” Id. at 4.

The Singh decision thus confirms that a fully informed, uncoerced vote of disinterested stockholders will generally serve to shield directors and advisors from post-closing damages claims. It also reaffirms the Supreme Court’s ruling in Rural Metro that advisors are not immune from liability even though there is no finding of gross negligence by the directors, while recognizing that standard still provides advisors with a “high degree of insulation from liability.” Id.

Disclosure-Only Settlement Approved After Trulia

As we discussed in a prior update, the Delaware Court of Chancery has strongly signaled of late that stockholder class actions attacking mergers may no longer be resolved by a corporate defendant providing additional disclosures to stockholders (and payment to plaintiffs’ attorneys) in exchange for a broad release of claims against all defendants. Notably, in his opinion earlier this year in In re Trulia, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 10020-CB (Del. Ch. Jan. 22, 2016), which was interpreted by many as the end of routine disclosure-only settlements in Delaware, Chancellor Bouchard warned that the Chancery Court “will be increasingly vigilant in scrutinizing the ‘give’ and ‘get’ of such settlements to ensure that they are genuinely fair and reasonable to absent class members.” Id. at 2. In so doing, Chancellor Bouchard suggested that, going forward, the Chancery Court would not approve disclosure-only settlements unless (i) the supplemental disclosures are “plainly material” and (ii) the releases provided to the defendants are narrowly crafted. Id. at 24.

Several weeks later, however, in In re BTU International, Inc. Stockholders Litigation, C.A. No. 10310-CB (Del. Ch. Feb. 18, 2016) (Transcript), Chancellor Bouchard approved a nonmonetary settlement on the grounds that it met the heightened standards articulated in Trulia. In particular, Chancellor Bouchard found that the supplemental disclosures at issue, which included projections used in the financial advisors’ analyses, satisfied the “plainly material” standard articulated in Trulia. Chancellor Bouchard similarly found that the scope of the release provided to defendants “would pass muster under Trulia” because it excluded “unknown claims” and was limited only to disclosure claims and fiduciary duty claims relating to the decision to enter the merger. Nonetheless, Chancellor Bouchard again emphasized the Chancery Court’s preference that such disclosure issues “be resolved in an adversarial process, either through actual litigation or in connection with a mootness fee application.” Chancellor Bouchard also noted that while the BTU settlement predated Trulia, future litigants “would be wise” to pursue mootness fee applications in similar situations.

SLUSA to Be Clarified for Securities Act Class Actions in State Court?

An important jurisdictional issue that has long divided the lower courts may be getting attention from the U.S. Supreme Court this coming term. That issue is whether state courts retain jurisdiction to hear class actions invoking the federal Securities Act of 1933 following the reforms Congress enacted in the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act of 1998 (“SLUSA”). After plaintiffs began end-running the procedural reforms in the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 by filing in state court, SLUSA preempted and provided for removal of certain class actions alleging securities fraud under state law, but courts have been unable to agree about whether (as would seem logical) SLUSA also precludes state court jurisdiction for Securities Act class actions. The question is important because unlike the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Securities Act contains a bar to removal for claims arising under its provisions, rendering SLUSA an important potential avenue to federal court apart from the federal-question removal statute (28 U.S.C. § 1331). In 2011, the California Court of Appeal held that SLUSA did not apply to federal claims, see Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal. App. 4th 789 (2011), which caused a tremendous proliferation of Securities Act class actions to be filed and litigated in the California state courts.

Now, the defendants in one such action have sought certiorari. Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, No. 15-1439 (U.S. 2016). The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has filed an amicus brief in support of the cert. petition, and after the plaintiff failed to timely respond, the Supreme Court ordered it to do so (by August 1).

Endnotes:

[1] Just two months later, on April 8, 2016, the Second Circuit addressed Omnicare in another summary order, but this time in the context of a claim under Section 18 of the Exchange Act. Special Situations Fund III QP, L.P. v. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA, Ltd., No. 15-1813-CV, 2016 WL 1392280 (2d Cir. Apr. 8, 2016). The appellate court upheld the dismissal of plaintiffs’ Section 18 claims on the grounds that the complaint failed to adequately allege facts supporting the claims of misrepresentations under Omnicare.

(go back)

Print

Print