Nicholas J. DeNovio is a partner at Latham & Watkins LLP. This post is based on a Latham publication by Mr. DeNovio, Jiyeon Lee-Lim, Laurence J. Stein, and Kirt Switzer.

Tax reform plans would fundamentally alter the landscape for key business decisions, impacting a business’ legal, finance, corporate development and other divisions, as well as tax groups.

Key Points:

- Tax reform would change taxation, capital and operating structures.

- The House Ways & Means Committee and the Trump Administration have each released tax reform proposals addressing five key themes: lowering the corporate tax rate, interest and other deductions, a territorial system, a one-time tax on accumulated overseas earnings and a destination-based cash flow tax.

- Forward-looking strategies can help parties keep transactions on track.

Introduction

As is readily apparent in the press, Congress, President Trump and the business community are intensely focused on tax reform in 2017. Multinational corporations, small businesses, financial services entities and investment and private equity funds are all surveying proposed changes, and many are involved directly or through industry associations in efforts to shape the policy discussion.

In June 2016, the House Ways & Means Committee released a report entitled “A Better Way—Our Vision for a Confident America” (the Blueprint) proposing fundamental changes to the US Internal Revenue Code (the Code). In addition, the President released a high level plan entitled “Trump—Tax Reform that Will Make America Great Again” (the Trump Plan) during the presidential campaign. While the House Ways & Means Committee and the Trump Administration are working on further developing these proposals, business leaders and in-house counsel are faced with the question of how to approach transactions (and, for listed issuers, public disclosures as well) in the face of such uncertainty.

Overview

Part I of this post summarizes the Blueprint’s five key elements (and, to a lesser degree, summarizes the Trump Plan)—which would significantly impact the taxation of businesses—and some of the collateral consequences of these plans.

Part II of this post summarizes the impact of these changes in a variety of transactional areas (M&A, capital markets, bank finance and securities disclosure) as well as the impact of these changes on certain industries. Some of the key issues businesses should consider in light of these proposed tax changes include:

- The potential approaches to M&A structuring and relevant documentation to help manage or mitigate the ultimate impact of any such changes

- The possible impact of the proposed changes on existing and future terms and structures utilized in the context of debt offerings and financings

- How to manage forward-looking disclosure in the context of capital markets transactions

Part I: Comparing the Blueprint and the Trump Plan: Five Highlights

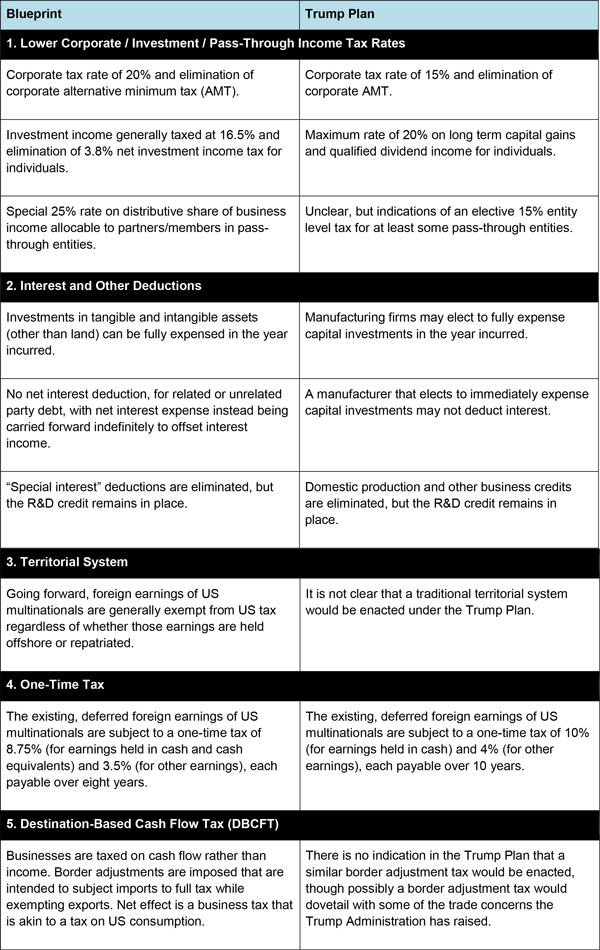

The below chart provides an overview of the five key issues of concerns to businesses. Each highlight is discussed in greater detail below.

While the plans do include a number of other proposed changes, this post focuses on the proposals related to these five key issues as well as the general issues already arising inside and outside of the US tax context as a result of these proposals.

1. Lower Corporate Tax Rates

The current top marginal corporate tax rate in the US is 35%, which exceeds (often significantly) the top marginal corporate tax rate applicable in many non-US jurisdictions. The changes to the corporate tax rate proposed in the Blueprint and the Trump Plan would generally bring the US corporate tax rate closer to that in many non-US jurisdictions and would create a preferential rate relative to some.

Valuation Impact. Subject to the impact of other proposals outlined herein, a significant reduction in the federal corporate tax rate may enhance the valuation of most companies with material US operations. However, this enhanced valuation may not apply to certain publicly traded vehicles, including Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs). In that case, a material reduction in the federal corporate tax rate and a low tax rate for certain investment income (such as qualified dividend income) for individuals may weaken or diminish the relative after-tax valuation advantage that investors in pass-through vehicles—including MLPs—have enjoyed relative to investments in corporations subject to double taxation.

Net Operating Losses (NOLs) and Other Deferred Tax Assets. The potential tax savings attributable to NOLs and deferred tax assets would be diminished by a reduction in the corporate tax rate, which could impact the value attributed to such assets (and the entities holding them) in acquisitions.

2. Deduction for Interest Expense

The current tax laws generally provide a strong incentive for US companies to finance their operations with debt rather than equity to the extent possible. A much heavier tax burden is placed on equity- financed investment as compared to debt-financed investment, primarily due to the deductibility of interest on debt financing.

The Blueprint would eliminate the deduction for interest expense, except to the extent of interest income. The Blueprint’s “policy quid pro quo” for the disallowance of net interest deductions is to allow the immediate expensing of investments. The Trump Plan, by contrast, would allow businesses to elect full immediate expensing or interest deductibility, though this likewise suggests a quid pro quo relationship between the two.

Impact on Capital Structure—Debt vs. Equity. By eliminating net interest deductions (either automatically in the case of the Blueprint or by election in the case of the Trump Plan), each proposal would take a significant step toward bringing parity to the US federal tax treatment of debt and equity. The initial reaction to disallowance of interest expense may be to consider debt unattractive from the issuer’s perspective. However, the question must be examined taking into account the several factors described below.

From the perspective of investors, debt financing may still provide several tax advantages beyond the benefit of providing various default remedies to a creditor. Non-US investors may be exempt from, or subject to, reduced rates of withholding on interest payments received under the portfolio interest exemption or under an applicable income tax treaty in a manner that such investors would not be with respect to dividends. If the borrower is a partnership engaged in any US trade or business, non-US investors or tax-exempt investors would generally prefer to hold debt of the partnership in order to avoid being treated as engaged in the partnership’s trade or business. Leveraged investors may prefer interest income so that they could offset such income with interest deductions (since interest deductions would only be disallowed to the extent the deductions exceed interest income). In addition, by equalizing the treatment of interest and dividend income, the Blueprint would eliminate preferred tax treatment currently available to US investors receiving dividends, such as qualified dividend income.

Ultimately, while the Blueprint and the Trump Plan may reduce or eliminate the incentive to pursue debt financing rather than equity financing for domestic companies, debt financing may still present significant benefits to foreign companies and multinational groups.

Impact on Capital Structure—Location of Debt. Because debt would generally no longer be deductible in the US, this change may incentivize businesses to push debt overseas, where an interest deduction may continue to be available and beneficial. Overseas debt may be especially appealing if a territorial system of taxation is also adopted (see below), because paying high tax in a foreign country would no longer bring the benefit of foreign tax credits that can be used to offset a US tax upon repatriation. Under a territorial system, foreign taxes become a pure expense.

Elimination of Competitive Disadvantage for US Companies vs. Foreign Companies—Base Erosion. Historically, foreign parented companies have offered an advantage versus US-parented companies because of foreign parented companies’ ability to use intercompany debt (subject to a number of restrictions, including the new Code Section 385 regulations) to base erode US earnings. With the elimination of all net interest deductions, such intercompany leverage would no longer achieve base erosion.

Grandfathering of Existing Debt. One question regarding this disallowance of interest deductions is whether the allowance of such a deduction would be “grandfathered” for debt outstanding at the time of enactment. Grandfathering outstanding debt would create a number of potential issues:

- Allowing the interest deduction for debt “in place” or “outstanding” at the time of enactment would raise significant administrative and IRS audit concerns, in the case of debt which has terms such as call, conversion, put or extension features.

- Interest rate fluctuations may result in a taxpayer having an economic incentive to retire debt, but not doing so if such debt is grandfathered and allowed an interest deduction.

- Grandfathering would make it all but impossible to “score” the revenue impact of an interest disallowance under a grandfathering transition rule. This grandfathering should be contrasted with a transition approach in which the overall interest deduction might be phased out, for example at 20% or 25% diminution intervals, over several years.

So while transition rules remain a matter of speculation, businesses should keep these considerations in mind while planning for the future.

3. Territorial Tax Regime

The US system of taxing the worldwide earnings of a US multinational dates to the origins of the Code. Earnings accumulated offshore are subject to US tax when repatriated, with an allowance for a foreign tax credit which, due to its own restrictions and complications, often results in a combined foreign and US tax that is higher than 35%. In 1962, the Subpart F rules were enacted, causing current US taxation in respect of foreign subsidiary income in certain situations.

One of the major complaints about the US tax regime is the taxation of worldwide earnings, along with an archaic controlled foreign corporation (CFC) regime enacted in a different era, as most US trading partners have enacted territorial regimes which greatly reduce or exempt the local tax on the overseas earnings of foreign subsidiaries. The territorial systems in the UK, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and elsewhere, along with systems like Ireland—which tax overseas earnings but provide a very generous credit allowance, for the most part resulting in no tax in Ireland—are seen as factors that played a significant role in the inversion/corporate expatriation trend over the last 20 years.

The Blueprint proposes a territorial system of taxation in which most foreign income is permanently exempt from US tax. The overseas earnings of US multinationals would be exempt from US tax when repatriated in the form of a dividend. The Subpart F rules, targeting operations and income of CFCs, would be largely eliminated except for a narrow category of passive income.

Reduced Foreign Tax Credit Planning. While reducing taxes foreign subsidiaries pay is a general goal of any US multinational, that goal would be sharpened in the case of a territorial system, as the local (foreign) tax would no longer generate a credit to offset an eventual US tax on repatriation. Rather, the local (foreign) tax would be a pure expense.

Use of Offshore Cash. The Blueprint’s territorial regime would solve the “lockout effect” on overseas earnings, allowing redeployment or repatriation of those future earnings to be utilized for investments (in the US or other parts of the world), debt repayment, share buybacks, dividends and M&A activity. Eliminating the lockout effect would change the fundamentals of an overall platform of a US-parented group, especially if coupled with the rate cut and, in particular, the border adjusted cash flow tax discussed in section 5 below.

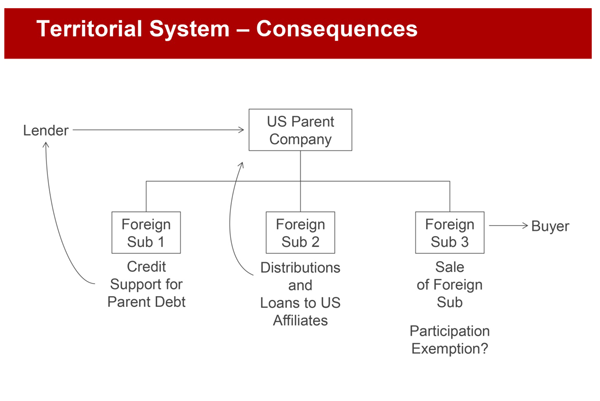

Credit Support From Foreign Subsidiaries. Under current law, loans by a foreign subsidiary to a US affiliate, or certain credit support from a foreign subsidiary for US debt, would likely result in a deemed repatriation of earnings to the US under Code Section 956. While the Blueprint does not include specific details about a territorial system, it would most likely eliminate Code Section 956. Thus, a territorial system would allow those loans or credit support to be provided without such a deemed repatriation cost. Part II of the post discusses this impact on financing structures in greater detail.

Participation Exemption on Sale. Previous bills providing for a territorial regime have included or discussed the notion of a full participation exemption on the sale of a foreign subsidiary. The Blueprint is silent on this precise issue, though the general principle of a territorial system combined with reference to elimination of “the bulk of the Subpart F rules” may indicate that such a participation exemption will be provided. If that is the case, a participation exemption would change the landscape for certain M&A considerations and structures. For example, following the acquisition of a US group with foreign subsidiaries, a buyer (whether US or foreign) might aim to divest certain non-US operations in order to pay down acquisition debt or to streamline operations. A participation exemption would provide flexibility to do so without triggering US tax on the embedded appreciation in the non-US assets.

The chart below illustrates these various consequences expected under the Blueprint’s territorial system.

4. Mandatory One-Time Tax on Accumulated Earnings Through Deemed Repatriation

Estimates vary on the amount of US multinationals’ overseas earnings that are deferred from US tax, but the Blueprint uses the phrase “more than $2 trillion,” which is in line with various studies.

Both the Blueprint and the Trump Plan propose a deemed repatriation of the accumulated foreign earnings of US corporations. The Blueprint would tax these earnings at a rate of 8.75% for cash and cash-equivalents and 3.5% for invested earnings, which would be payable over eight years. The Trump Plan would tax foreign earnings at a rate of 10% for cash and 4% for other earnings, which would be payable over 10 years.

In 2005, Congress and the Bush Administration enacted a one-time repatriation holiday, allowing companies to elect to actually repatriate overseas earnings at a 5.25% rate, provided the amount was invested in various categories. Under the 2005 rule, any earnings that remained offshore were not taxed, but rather continued to be deferred. Importantly, while both plans lack certain specifics, all indications are that the Blueprint and the Trump Plan envision a mandatory deemed repatriation, rather than the voluntary and elective repatriation holiday that occurred in 2005. Accordingly, all US companies with foreign earnings would be subject to the tax regardless of whether or not they repatriate their foreign earnings to the US. Hence, there would be no incremental tax cost to repatriating these accumulated foreign earnings.

Share Buybacks and Special Dividends. While the general subject of fundamental tax reform has attracted widespread attention in the business press, one particular topic has been a significant focus: the effect of the deemed repatriation of accumulated foreign earnings. The common theme in the press has been that a large portion of the overseas earnings brought back to the US would likely be used to fund share buybacks and one-time dividends. At the same time, other commentators have noted that companies should engage in buybacks only when they are confident that the return on those buybacks will ultimately exceed the long-term returns of investing in future growth at the company level. [1]

5. Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax

The Blueprint’s most revolutionary (and controversial) proposal is the Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax (the DBCFT). As the name implies, there are two different aspects to this proposal. First, the DBCFT would re-orient the taxation of businesses so that a tax is imposed on the cash-flow of a business rather than its income. Second, it would add “border adjustments.” Each point is considered in turn below, with the caveat that this is a new and complex tax and very few of the details have been fleshed out to date, so by definition some of the analysis below involves a certain degree of extrapolation. The post then examines some of the consequences that would result from the DBCFT.

Cash Flow Tax on Business Activity

The notion of a cash-flow tax is that cash inflows would be included in the tax base while cash outflows would be deducted. This is akin to a consumption tax or a sales tax (or a value added tax (VAT)), where a tax is levied on cash inflows less cash outflows—though policymakers are cautious not to refer to this tax as a VAT. The DBCFT achieves a cash-flow tax by allowing the immediate expensing for all business investments, so that the amount paid for a business asset would be deducted upfront, rather than incorporated into a basis for the asset. Wages would also be deducted, so that in effect all cash outflows are deducted. Any resulting NOL would have to be carried forward. The tax would subsequently be imposed on the gross receipts generated by business assets (including the proceeds from the ultimate sale of the asset), without any basis offset.

Note that no effort is made under the DBCFT to match the timing of the deduction for a given expenditure to the receipts that the expenditure ultimately gives rise to. By contrast, this timing aspect is a key concept with an income tax.

Border Adjustments

The above is the “cash-flow tax” part of the DBCFT. The “destination-based” part of the DBCFT is achieved via border adjustments, as explained below.

The proposed border adjustments would exempt US exports from tax but fully tax US imports.

Specifically, for US exports, all revenue (not just profit) from exports would be exempt. By contrast, for US imports, the cost of goods sold would not be deductible, so that when a US company sells an imported good in the US, it would be taxed (at the 20% corporate tax rate) on the full revenue received (not just profit). The intent is that products, services and intangibles that are exported outside the US will not be subject to US tax; whereas products, services and intangibles that are imported into the US will be subject to US tax regardless of where they are produced. Thus, the net effect is to impose tax on items that are consumed in the US, regardless of where they are produced. Therefore, the cash-flow tax (which as noted above is akin to a tax on consumption) becomes, in effect, a tax on US consumption. Also notably the tax would appear to apply in the same manner regardless of whether the ownership of the business operations is US or foreign.

Collateral Consequences

The DBCFT, as an entirely new tax system different from any previous US tax regime, has—not surprisingly—raised numerous questions, some of which are briefly considered below.

Importers vs. Exporters. At first blush, importers will appear to have an increased tax burden as they would effectively be paying tax at 20% on the full revenue received from the sale of imported goods, rather than just the profit on those goods. Thus, imported goods would likely need to be marked up 25% (e.g., from US$100 to US$125) to offset the 20% tax (e.g., US$125 less a 20% tax yields a net receipt of US$100). A similar but opposite effect would seem to occur with respect to exporters. However, economists suggest that the DBCFT would cause the dollar to rise 25%, which would then offset these effects of the DBCFT on importers and exporters. This prediction has, in turn, generated much commentary as to whether the currency markets would, in fact, work as efficiently as some have suggested.

Complex Supply Chains. The foregoing discussion has explained the DBCFT with relatively simplistic concepts (e.g., the sale of an imported good versus the sale of an exported good). However, for many businesses, their supply chains are in fact much more complex. Consider, for example, a product which is partially manufactured in the US, then exported to a foreign country for assembly, then imported back to the US. How the DBCFT would apply to such a supply chain is unclear.

WTO Concerns. The World Trade Organization (WTO) allows border adjustments similar to those proposed in the Blueprint (which are viewed as a subsidy for exports) only for indirect taxes (e.g., a VAT). Indeed, many of the US’ most significant trading partners impose tax on imported products while excluding exports from tax under their VAT system. For this reason the Blueprint argues that the US’ failure to make offsetting border adjustments “amounts to a self-imposed unilateral penalty on US exports and a self-imposed unilateral subsidy for US imports.” [2] However, because the WTO permits these types of border adjustments only for indirect taxes, this raises the question of whether the WTO would, in fact, view the DBCFT as an indirect tax, akin to a VAT. If the WTO were to view the DBCFT as a direct tax, then the US could find itself in contravention of WTO law and subject to retaliation by other WTO member countries.

Corporate Organization

Potential Effect on Place of Incorporation

One of the intended effects of the changes proposed in each of the Blueprint and the Trump Plan is to diminish the incentive for companies to establish or relocate their legal headquarters and/or significant operations in or to non-US jurisdictions. In this regard, eliminating the corporate AMT and significantly reducing corporate tax rates—as included in the Blueprint and the Trump Plan—would bring effective tax rates closer to parity with many non-US jurisdictions.

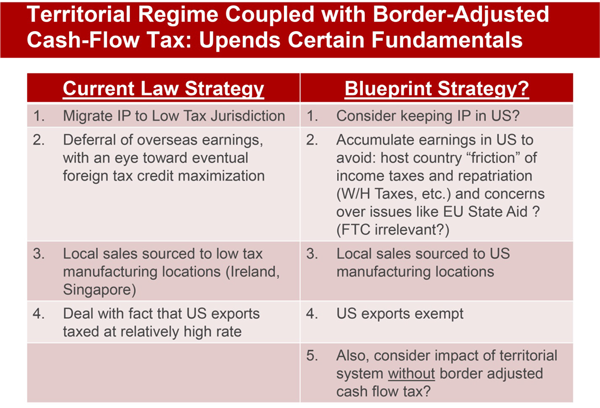

Similarly, the fundamental transformation from a worldwide, residence-based income tax system to the type of territorial, cash-flow tax system that the Blueprint proposes in the form of the DBCFT would bring the US closer to neutrality in terms of taxation of resident corporations.

In addition, the combination of a lower corporate tax rate and the DBCFT is intended to reverse the benefits currently associated with locating production of goods (including IP) in a non-US jurisdiction. In particular, the ability to immediately expense the cost of production provided under the Blueprint (automatically) and the Trump Plan (pursuant to an election), and to then export those products to customers or affiliates without being subject to US federal tax, provides a strong incentive to carry out such production in the US.

While these and the other changes currently proposed under the Blueprint and the Trump Plan may ultimately reduce or eliminate the tax benefits associated with locating a company’s operations in a non- US jurisdiction, the tax considerations may not justify reincorporating in the US in the near term. Numerous considerations will arise in regards to such an action, including the inherent uncertainty that comes with such a transformative shift in tax policy. In addition, given that either the Blueprint or the Trump Plan would fundamentally change a century of US tax policy, the global business community may well take time to adjust and change what have been common planning goals.

The Blueprint’s territorial system and the DBCFT, when combined, would cause fundamental changes in international and cross-border tax planning, as illustrated in the following chart.

Part II: Summary of Certain Key Transactional Considerations

As illustrated above, the proposals in the Blueprint reflect a potential sweeping overhaul of the US corporate tax system. While uncertainty remains regarding which, if any, of the proposals will be enacted, there is a high expectation in the business community that some form of tax reform will become a reality in the near term. This section summarizes the key considerations for executing capital markets, finance and M&A transactions, and for complying with SEC disclosure requirements, in light of this uncertainty. This section also considers the impact on certain industries.

Capital Markets

The proposed reforms would impact the factors issuers consider when they determine where to raise capital and whether to do so by issuing debt or equity. The lower stakes of recasting debt as equity (and vice versa), may result in the use of more hybrid instruments tailored to meet the specific economic needs of the issuer and the market rather than to satisfy traditional definitions of debt or equity. Similarly, proposed changes to the deductibility of interest expense could also reduce the relative disadvantage of pay-in-kind debt with a maturity longer than 5.5 years (when compared to cash-interest-paying debt), which exists under current tax law. Whether, during the interim period until adoption of any of the proposed tax reform, bespoke redemption provisions emerge that allow bonds to be redeemed at a reduced premium upon a change in the deductibility of interest expense remains to be seen. Alternatively, there may be a rush to issue debt in advance of any deadline that may be set for debt to be “grandfathered” (if that is part of an adopted regime). Note the discussion above regarding the challenges policymakers might face in deciding whether to allow grandfathering.

Finance

The Blueprint’s territorial system, as noted above, would likely eliminate Code Section 956. The elimination of Code Section 956 would allow non-US subsidiaries to both borrow directly and then upstream proceeds of such borrowing or to simply provide guarantees and security for global credit support.

Additionally, as discussed above, the unavailability of a US net interest deduction may cause multinationals to push debt to their foreign affiliates that can benefit, under local tax law, from net interest expense.

The removal of Code Section 956 may also affect existing credit agreements, in that, depending on the wording of the relevant credit documents, additional guarantees or security, or mandatory prepayments, may be triggered.

M&A

In the context of M&A, the implications of pending tax reform may cause difficulty in planning and executing deals. Most commentators attempt to provide guidance for deals that may be agreed to after the effective date of tax reform, as to which the consequences of reform would then be foreseeable, such as offshore cash coming onshore or changes in deductibility. Of equal concern, however, are pending deals that may be entered into while reform is pending. During this period the definitive deal terms and timing may be clouded, including as to how the future value of an acquired business may be meaningfully impacted by the contemplated tax reform. The issues to be considered for M&A transactions taking place during this interim period are outlined below.

Tax Attributes

A target’s tax attributes can have substantial implications for value and deal structure. Net operating losses, for example, are often used by the acquirer to shelter income. The value of that use is often reflected in the purchase price. If lower tax rates are implemented, that attribute has less value to the buyer and, as a consequence, will receive less consideration in the value of the purchase price. Conversely, the Blueprint preserves and enhances the notional value of net operating losses which could potentially compensate for any diminished value associated with lower tax rates.

Changes to corporate tax rates create similar valuation implications for depreciation deductions. However, as noted above, the Blueprint provides for the immediate deduction of investment costs, which may include the cost of acquiring business assets and which would enhance the tax benefits of asset investments/acquisitions and perhaps compensate for any diminished value associated with lower tax rates.

Financing

As commitments begin to reflect the uncertainty and risks associated with tax reform—particularly those commitments that are longer dated—covenant packages and even conditions of closing may become tied to the terms and timing of the implementation of tax reform. Such tying may result in a discontinuity between the conditions of closing for the underlying transaction and the financing, creating uncertainty for the buyer, seller or both.

Deal Structure

If immediate deduction is obtainable, buyers will prefer asset deals over stock acquisitions. Two elements of friction, however, are worth considering. First, taxation at the corporate and shareholder level will result in an additional tax cost to the seller. Whether the reduction in effective rates will offset this cost sufficient to overcome this friction will depend on the final terms of reform. Second, there are transaction costs associated with asset transfers as well as commercial concerns regarding assignment of contracts and similar agreements. Even so, the Blueprint’s provision for immediate deductibility may drive asset structures in whole or in part.

Structural Costs Associated with Operating Structures

Certain changes included in the Blueprint may have significant implications for the structural costs of operating structures. Among these, the mandatory one-time tax on accumulated earnings, the DBCFT and the implementation of a territorial system may affect the amount and destination of a business’ cash flows. For example, if a US target has substantial offshore production, its cash flow after taxes could be adversely impacted. Conversely, “trapped cash”—cash and cash equivalents that historically cannot be repatriated except at a substantial tax cost—will be calculated fairly differently, as offshore cash can be repatriated with lesser or no tax cost in the long run (or conversely there will be a near-term one-time significant tax cost associated with legacy offshore profits), and the acquisition agreement will likely want to account for this trapped cash in, for example, the calculation of working capital.

Domicile of Holding Company

The potential for tax reform and Brexit have furnished the proverbial perfect storm as parties in cross- border mergers work to decide on the corporate and tax domicile for the combined companies. Many of the combinations in recent years have chosen the UK for a variety of reasons, including tax efficiencies. Notwithstanding the Brexit uncertainty and the prospect of the US adopting historically low corporate rates, in the near-term, parties will likely continue to utilize non-US domiciles for holding companies. The UK will likely remain attractive for reasons beyond tax efficiency, including soft considerations associated with governance and other concerns, as well as the uncertainty associated with the specific terms of legislative and regulatory implementation of tax reform in the US.

How Should Principal M&A Agreements Best Address Tax Reform Uncertainty?

The Challenges

From the seller’s perspective, it’s important to avoid unintended traps in representations and warranties. This concern is more applicable to private deals rather than public, since generally these representations are brought down to closing by way of a material adverse event provision. However, private deal representations can be brought down to closing on a materiality standard.

Purchase price adjustments may also become distorted. A company’s working capital may be reduced due to increases in tax costs. Thus, valuation for purposes of working capital adjustments would likely need to be addressed as well as the ability to repatriate trapped cash.

In addressing fundamental value implications of tax reform, buyers may find the material adverse change (MAC) condition too blunt and unreliable an instrument for instilling confidence in creating an effective buyer termination right. A MAC condition customarily provides exclusions for changes in law, including tax law. However, the seller would likely argue that such changes were foreseeable under the circumstances.

Conversely, the “disproportionate effect” exception to industry-wide changes in a MAC condition may create issues for the seller. These carve-outs for similarly situated companies are often limited by the disproportionate effect on a single company. Viewed through the lens of a MAC condition, a US manufacturing company with substantial offshore production may be affected disproportionately as compared to a company in the same industry but with substantial onshore production.

Alternative Approaches Now

Despite the uncertainty attendant to tax reform, parties may employ the following practical strategies when executing deals in the face of such uncertainty:

- Consider including an affirmative disclaimer specifying that none of the representations and warranties will be deemed breached or any condition failed as a consequence of tax law changes.

- If fundamental elements of value may be impacted by tax reform, the parties may want to negotiate termination rights associated with the enactment of certain changes.

- Conditions linked to tax treatment of the transactions may require particular scrutiny.

- Even at the earlier stages of the delineation of tax reform, parties may wish to seek good faith covenants on more narrow and manageable issues. For example, an obligation to negotiate or restructure in good faith or to adjust consideration so as to mitigate, reflect or reduce the consequences of tax changes may be prudent. If a substantial difference between the purchase price and tax basis arises, a covenant providing for flexibility in opting for a stock or an asset acquisition structure may similarly enhance tax efficiencies.

- As reform progresses and its terms become more specific, some issues may be addressed by alternative formulae in the acquisition agreement. For example, there may be differing treatments of trapped cash, accumulated and previously untaxed earnings and accrued taxes for circumstances in which either (1) tax reform implements a territorial system and a one-time deemed repatriation or (2) the trapped cash remains subject at closing to an excessively high tax cost if repatriated to the US.

SEC Disclosure

The Blueprint’s proposed reforms introduce disclosure issues for public companies’ compliance with the federal securities laws relating to periodic reporting and capital markets transactions. The Blueprint’s potential impact presents significant uncertainty that companies must manage. In the short term, revisions to tax-related disclosures may well be merely incremental, and companies may need to move quickly to revise related disclosures as circumstances change.

Recent disclosure trends indicate that most companies have not adopted significant changes to their disclosures in response to the proposed tax reforms. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires public companies to disclose the “most significant factors” that make an offering “speculative or risky” while excluding disclosure of “risks that could apply to any issuer or any offering.” At this early stage, discussion of contemplated reforms would likely be too vague and generic to be meaningful to investors. Moreover, many companies already disclose the risk that tax law changes could affect their business, results of operations and financial condition. In other words, what can be said to date has already been said.

Companies that have adopted new disclosures in response to the Blueprint have generally made incremental changes with surgical updates to risk factors and management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operations (MD&A). Most commonly, these companies have supplemented their existing disclosure with references to uncertainties relating to tax reform and the new administration’s interest in pursuing major changes in tax law.

A smaller number of companies have included greater detail in their disclosures, including possible implications of specific reform risks specific to their businesses. For example, an alternative energy company might discuss risks to solar energy tax credits, and an investment manager may highlight the possible impact of changes in the corporate tax rate. In some instances, companies have addressed potential tax reforms outside of their SEC periodic reports, such as through earnings calls, supplemental proxy materials and letters to shareholders.

Companies can expect they will need to monitor further developments in this area and respond quickly and flexibly when changes do occur. In the near term, companies may wish to review existing disclosures in light of the possible tax reforms and consider adding language where appropriate. However, companies may find updating their disclosure difficult until the likely trajectory of the proposed reforms becomes clearer.

Companies may wish to consider how tax reforms could affect their business, industry and macroeconomic trends, as well as the possibility that other countries could adopt measures in response to any major changes in US tax policy. Companies likely will want to confirm that the existing disclosure adequately addresses the uncertainties and potential risks of tax reform generally. Key disclosures for companies to review would include risk factors, MD&A, forward-looking statement disclaimers and financial statement footnotes.

If the Blueprint’s reforms go forward, changes could occur rapidly. Recommended steps include reviewing a company’s disclosure regularly, staying abreast of political developments, and consulting with legal and financial advisors as appropriate.

Special Industries

Renewable Energy

Certain forms of renewable energy projects in the US, including wind and solar energy, are heavily subsidized by tax credits and deductions in the Code. These projects are commonly financed through tax equity arrangements, under which US-based banks, insurance companies and large corporates make use of tax subsidies in exchange for providing project finance capital. Proposals to lower the corporate tax rate may decrease the tax liabilities of large US-based taxpayers, potentially diminishing the supply of this capital source. Further, lower corporate tax rates reduce the marginal benefit of tax deductions, thereby implicitly increasing the cost of tax equity financing. Capital providers and sponsors in this sector have begun adding features to loan and tax equity documentation anticipating the economic effects of future tax law changes and allocating the risks among the parties.

REITs

Although tax reform efforts have not yet included provisions directed specifically at REITs, some of the proposed changes could reduce the relative tax benefit of qualifying as a REIT. If corporate tax rates are reduced and non-REIT dividends payable to individual shareholders continue to be taxed at lower rates than dividends received from REITs, qualifying as a REIT could be less advantageous than it is under current law. Moreover, immediate expensing of certain assets and/or eliminating the net interest deduction would impact a REIT’s taxable income and, in turn, distribution requirements. International tax reform could also impact various aspects of the taxation of REITs. Even with these changes, investors may still wish to invest in US real estate through a REIT. Also, tax-exempt investors may find a REIT structure attractive since dividend income generally does not constitute unrelated business taxable income (UBTI). Similarly, dividends of operating income received by a non-US investor generally are not treated as effectively connected income.

Conclusion

The business community will be intensely focused on tax reform over the coming months. As the above discussion indicates, the consequences will be far-reaching. In the meantime, transactions will proceed with all parties considering the impact of reform on value, risk and other key economic factors.

Endnotes

1See Blackrock Chairman Larry Fink’s 2017 annual letter to CEOs, available at https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/en-no/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter.(go back)

2See Blueprint, page 28, available at https://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf.(go back)

Print

Print