Mathew Nelson is Global Leader of Climate Change and Sustainability Services at EY. This post is based on an EY publication.

EY member firms are able to conclude from several years of research of ESG reporting that there is a global trend toward increased interest in nonfinancial information on the part of investment professionals. But the question we continue to seek to answer is whether ESG information is, ultimately, influencing investor decisions. In each of the last three years, research undertaken by EY has documented an expanding role of ESG factors in the decisionmaking of investors around the world.

Recent headlines reflect why meaningful ESG analysis is increasingly important for institutional investors and the companies they follow. “Larry Fink Wants Companies to Talk More About the Future,” declared Bloomberg Media when the head of the world’s largest investment manager wrote to the CEOs of public companies to extoll the virtues of strong ESG performance and its effect on valuation. Nearly 200 nations met in Paris to negotiate and sign a global climate agreement that will shift financial markets. And one of the world’s largest automakers was embroiled in an unprecedented emissions-testing scandal. These and other news-making events in recent months have propelled ESG to the top of the global agenda. This is despite continued uncertainty in the regulatory environment globally.

This year’s report on ESG and nonfinancial reporting, available here, provides insights into the views of more than 320 institutional investors on nonfinancial reporting by publicly traded companies and the role ESG analysis plays in their investment decision-making.

Key findings

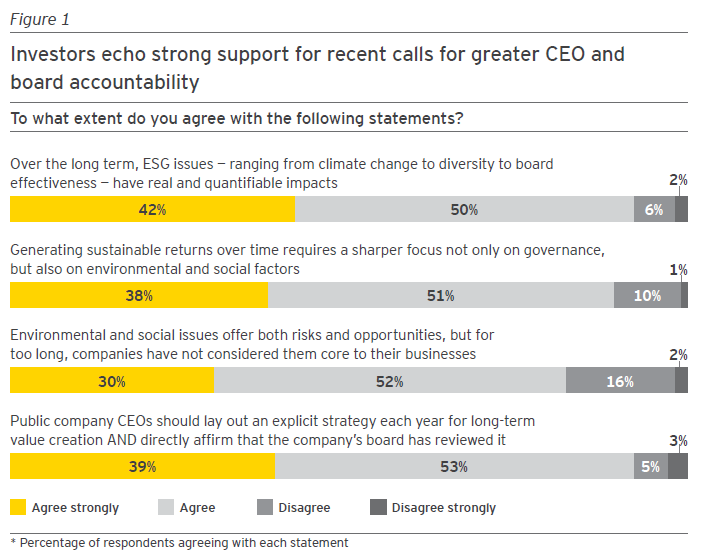

Investors around the world reveal broad support for the ESG-related themes expressed in the February 2016 memo from Laurence Fink, Chairman and CEO of BlackRock, to the leadership of the world’s largest companies. Investors strongly support Fink’s call for an annual board-approved strategy statement for public companies. They agree that ESG factors present risks and opportunities that have been neglected for too long. Yes, say investors, sustainable returns require a sharper focus on corporate governance and on environmental and social factors.

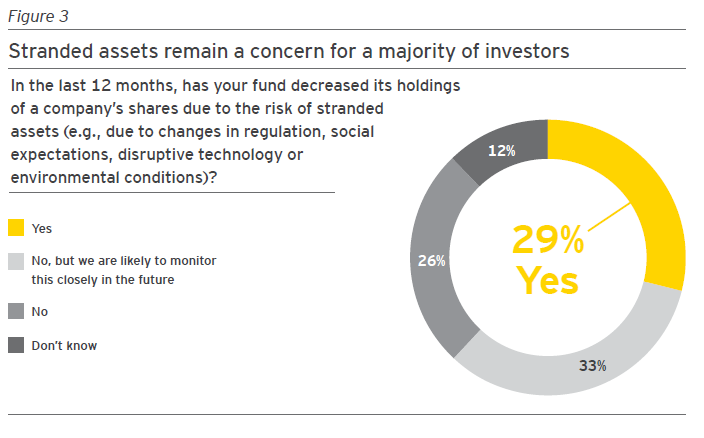

The risk of stranded assets remains a substantive concern for institutional investors, continuing a trend documented in last year’s report. More than 60% of the investors in our 2016 survey reported recently decreasing their holdings or monitoring holdings closely due to stranded asset risk.

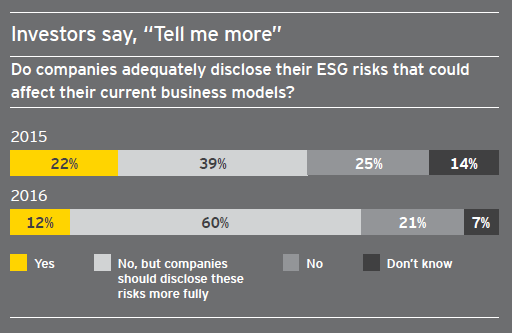

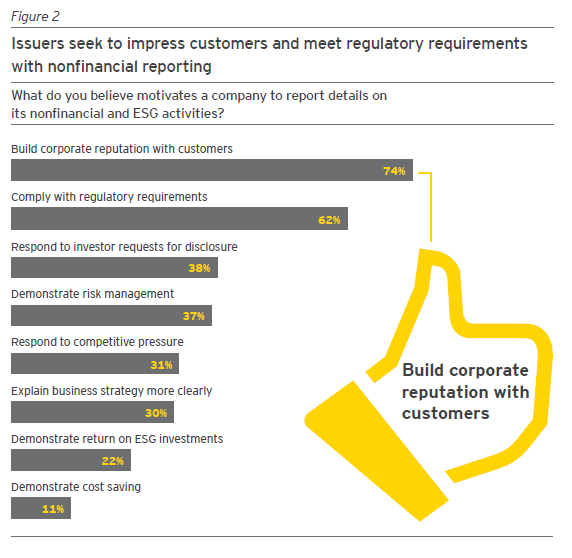

Investors believe the biggest factors motivating companies to report ESG information are the reputation of companies with their customers and regulatory compliance mandates. Most investors believe that companies don’t disclose ESG risks that could affect their business.

Despite the increasing importance placed on nonfinancial performance and disclosures, most of the surveyed investors evaluate environmental and social factors on an informal, not structured, basis.

Disclosure and scrutiny of nonfinancial information will continue to grow in importance in the years ahead. The Paris Climate Conference agreement will lead to an increase in disclosures about companies’ climate practices and risk management strategies, say investors. They report that recent environmental and social scandals have driven them to reevaluate nonfinancial disclosures and look more closely at available information.

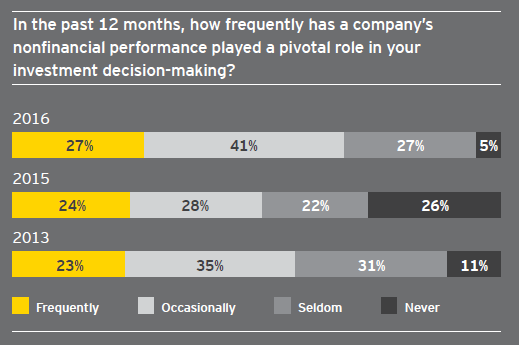

Nonfinancial performance plays a pivotal role in the investment decisions for most of the surveyed investors, and for a greater percentage of investors than in previous years. Also, a dwindling percentage of investors believe that it is unclear whether nonfinancial disclosures are material, down substantially from surveys in 2015 and 2013.

Investors see long-term financial benefits in companies with high ESG ratings

The ESG investing movement received a shot in the arm in February 2016, when the chairman and chief executive officer of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment manager, sent a memo to the CEOs of the S&P 500 companies and Europe’s largest corporations. His message: focus more on long-term value creation rather than short-term dividend payouts; be open and transparent about growth plans; and focus on environmental, social and governance factors because they have “real and quantifiable financial impacts.”

Laurence Fink, whose BlackRock has US$4.6 trillion under management and US$200 billion in sustainable investment strategies, also made a point that mirrors the argument made by many investors who track ESG performance: handling ESG issues well is often a sign of operational excellence at a company.

Our survey of investors found broad support for ESG-related themes expressed in the Fink memo. More than 80% of the survey respondents agreed with four statements related to Fink’s points: that CEOs should lay out long-term board-reviewed strategies each year; that companies have not considered environmental and social issues as core to their business for far too long; that generating sustainable returns over time requires a sharper focus on ESG factors; and that ESG issues have real and quantifiable impacts over the long term (see figure 1).

Investors who remain skeptical about the value of nonfinancial factors tend to disregard any causal relationship between a company’s ESG performance and financial performance. However, it’s commonly understood that serious reputational and environmental risks can and do surface, and they can have very real impacts on the bottom line. Investors who used ESG factors in their analysis point to the long-term benefits of investing in companies that pay close attention to ESG factors, as well as the lower investment risk with those companies.

ESG factors can help in identifying new opportunities and in managing long-term investment risks, avoiding poor company performance that can come from lax governance, or from weak environmental or social practices, says Matt Whineray, chief investment officer of the NZ$30 billion New Zealand Superannuation Fund.

Whineray points to two meta-studies that support the business case for ESG investing. A 2015 report by Oxford University and Arabesque Asset Management—based on more than 200 academic studies, industry reports, newspaper articles and books—found that 88% of the research reviewed shows “solid ESG practices” at companies lead to better operational performance, and that 80% of the studies analyzed showed that a company’s stock performance is positively influenced by good sustainability practices. [1] Another report, by Deutsche Bank in 2012, which looked at more than 100 academic studies, concluded that ESG factors are correlated with superior risk-adjusted returns. [2] The Deutsche Bank study also found that academic studies that tracked fund returns in the “socially responsible investing (SRI)” category may have turned up mixed or neutral results because many SRI managers have historically used exclusionary screens rather than the positive best-in-class investment approaches favored by ESG investors.

Related research undertaken by Harvard Business School and the London Business School, provides evidence that “high sustainability” companies significantly outperform their counterparts over the long term, both in terms of stock market as well as accounting performance measures. [3]

ESG analysis provides investors with an additional lens for reviewing and evaluating companies and assets, not just for equity performance, but for factors that affect bond pricing and real asset valuations, says Adam Kirkman, head of ESG at AMP Capital. The Australia-based investment manager with US$120 billion under management maintains an internal proprietary model portfolio of stocks rated highly based on ESG risk management factors, and the portfolio outperforms relevant indices of stocks not based on ESG factors.

Kirkman also points to specific examples: When AMP Capital’s analysts had concerns about some mining companies that were unable to demonstrate acceptable management of environmental and social risks, they underweighted the companies in their portfolio—a move that boosted the overall portfolio’s performance by 11 basis points over one year, relative to what the return would have been without the rebalancing move. The firm’s analysts had similar ESG concerns with a retailer’s stock, so they underweighted the stock and saw a 52-basis-point one-year relative improvement in the portfolio because of the move.

Engaging companies on ESG, even before issues of concern arise, gives investors the ability to influence outcomes that will maximize investment performance, says Kelly Christodoulou, ESG investments manager for AustralianSuper, the AU$100 billion pension fund. Engaging proactively also helps build relationships that can be fruitful if investors need to talk to company management in the future about concerns that arise.

Three years of data beginning to suggest an inflection point

Institutional investors have developed a greater appreciation for the value of ESG factors in the past several years. Three years of survey data, interviews with investors, and recent events and global initiatives offer evidence that ESG information plays an increasingly influential role in investment decision-making.

Analysis of ESG and other nonfinancial information is not a flash-in-the-pan trend among institutional investors.

While the broad change in investor sentiment cannot be attributed to a single incident or cause, it seems that we have reached a subtle but noteworthy inflection point, and ESG investing has entered the mainstream. This is despite the global uncertainty on where ESG policy development is going.

ESG analysis has evolved over the last decade, from an early emphasis by investors on governance issues to a broader interest in recent years on environmental factors, says Jennifer Anderson, who serves as the Responsible Investments Officer for the Pensions Trust in London, which manages more than £8 billion.

In the past, says Anderson, “the priority was always the governance side. Corporate governance—that was the area that had the most weight or relevance for investors. But in the last year, climate change has really accelerated, environmental risks have really gone up the agenda, and at the moment they seem to be of equal weight and importance in the discussion.”

Recent events have shown that there are material risks and benefits embedded in nonfinancial information from corporate issuers. Investors increasingly see that by understanding these risks and benefits, they can avoid the downside and embrace the upside in a valuation that flows from nonfinancial business activities. And their enthusiasm for analysis of nonfinancial information seems well-founded. Investors often expect that the rising population of millennials—with their views about ESG issues, and the influence gained as an estimated US$30 trillion is transferred to them from their parents and grandparents—will continue to amplify the importance of ESG factors in investing.

In each of our three studies, we asked investors how frequently a company’s nonfinancial performance had played a pivotal role in their investment decisions in the previous 12 months. In 2016, 68% responded that nonfinancial information played a pivotal role frequently or occasionally, up from 52% and 58% in 2015 and 2013, respectively. Thus, the proportion of investors relying on nonfinancial information—especially those doing so occasionally—has grown notably. More than four in ten respondents say nonfinancial information occasionally plays a pivotal role in decision-making, which suggests that investors and analysts may take an opportunistic and broad-minded approach to their evaluation of nonfinancial information.

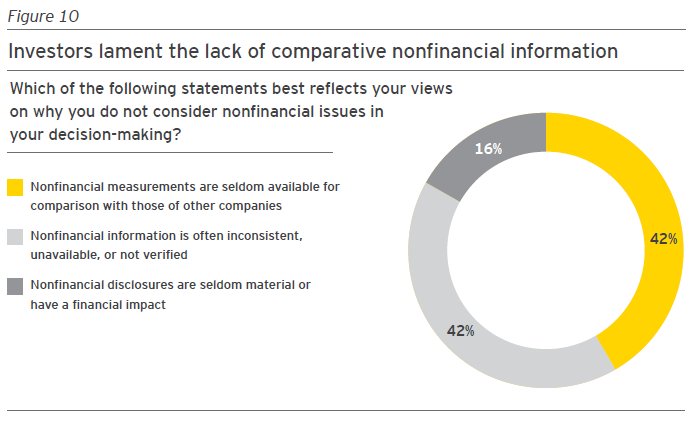

As investors acknowledge the impact of nonfinancial information in their decision-making, the proportion who dismiss nonfinancial and ESG information as immaterial or trivial has fallen. We asked about why investors wouldn’t consider ESG issues in their decision-making, and 16% said that it was unclear whether nonfinancial disclosures are material or have a financial impact. That sentiment was down dramatically from 2015, when 52% of the respondents weren’t sold on ESG materiality, and 2013, when 60% of the investors in the survey were unclear as to the potential materiality.

Investors increasingly see a pivotal role for nonfinancial information in investment decision-making

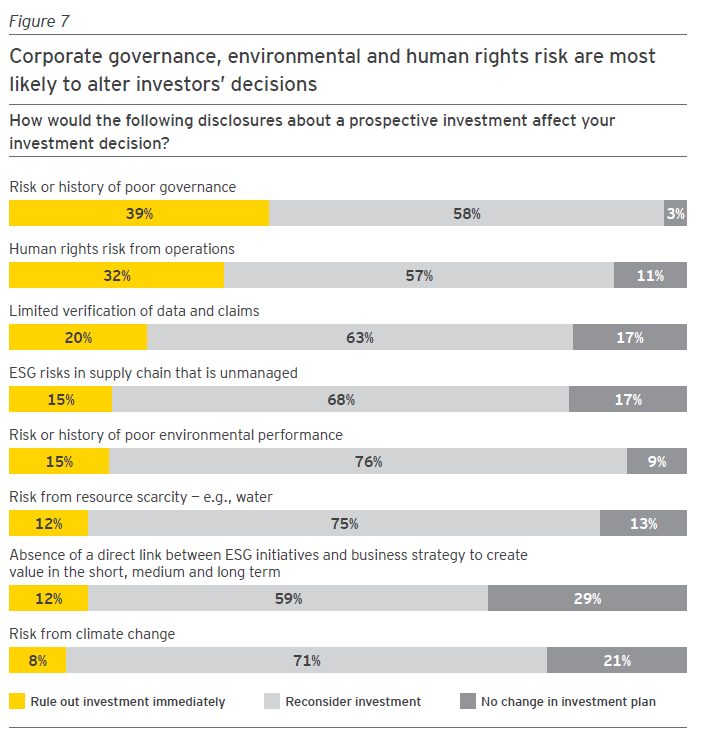

The surveys also indicate a trend toward a greater understanding of the significance of certain ESG disclosures, including corporate governance risks and those related to the treatment of employees worldwide. When investors were asked how the disclosure of a prospective investment’s risk or history of poor governance would affect an investment decision, 39% of the respondents in the 2016 survey said they would rule it out immediately, compared to 27% in 2015 and 30% in 2013. When asked about the disclosure of human rights risk from operations, 32% said they would rule it out immediately, compared to 19% and 22% in 2015 and 2013, respectively (see figure 7).

Amid the growing appreciation for ESG information, there appears to be a troubling dissatisfaction among investors with the quality of information available from issuers. In years past, one-third of respondents or fewer said they didn’t use nonfinancial information because it was often of poor quality. Now, as investors come to see nonfinancial information as increasingly material, they reveal still higher expectations for it being timely, comparable and verifiable.

Investors are growing more demanding, curious and discerning.

When asked about why they wouldn’t consider ESG issues in their decision-making, 42% of respondents in 2016 indicated that nonfinancial information is often inconsistent, unavailable or not verified, up from 32% in 2015 and 20% in 2013. Similarly, a growing plurality of respondents say nonfinancial measurements are seldom available for comparison with those of other companies, which garnered a 42% response in the 2016 survey, up from 16% in 2015 and 20% in 2013.

Finally, investors’ views on the quality of nonfinancial information provided by issuers may serve as a poignant wakeup call to chief financial officers and their corporate peers who seek the attention of institutional investors. Asked whether companies adequately disclose ESG risks that could affect their current business models, more than 80% of respondents said no. A solid majority—60%—called for companies to disclose these risks more fully.

What motivates companies’ nonfinancial reporting?

If investors want more issuers to report on their ESG activities, what motivates companies to disclose that information? According to our surveyed investors, the biggest motivating factor for most companies remains building their corporate reputation with customers, followed by complying with regulatory requirements (see figure 2). Investor demands play a role as well, along with the incentive of improving stock valuations, but to a much lesser degree.

“I think companies now are clearly aware that talking about corporate social responsibility is really part of their reputation, and on the way they convince people that there is good management of their business,” says Jacky Prudhomme, head of ESG integration and social business investments at BNP Paribas in Paris. “So I think now that most companies do play the game.”

Institutional investors have said that company managers also enjoy the recognition that comes when their companies are named in the lists of ESG leadership companies, or special ESG-focused indices or portfolios. Companies that are focused on nonfinancial performance issues actually want to be judged versus their peer companies, investors say, and company executives advocate for uniform ESG disclosure standards that may help make those evaluations possible.

Extensive ESG disclosures from a company can also indicate that it is part of an industry sector motivated to convince the financial community that it has a future, in spite of environmental pressures. “For me, it’s clearly a demonstration by the company that they’re thinking of an evolution or transformation of their business,” Prudhomme says.

The results of ESG initiatives and communication may also affect the company’s stock price. That’s why many CEOs now talk about ESG during quarterly results announcements or annual investor meetings, and they invite people in the socially responsible investing or ESG community to face-to-face meetings, Prudhomme says.

Certain institutional investors have been able to identify excess return opportunities when companies improve their ESG ratings, which ties ESG performance to investment opportunities. And for companies that are craving credit and recognition for their ESG performance, investors may demonstrate their recognition through how much they are willing to pay for stock.

Another motivating factor for companies to report and engage on ESG issues is to protect themselves from proxy ballot fights over social and environmental issues. BlackRock’s Fink indirectly threatens that the investment behemoth will back activists if companies don’t make long-range planning a priority, with the help of a focus on ESG factors.

Satisfying investor demand for ESG information has become more and more difficult for companies. Companies have been reporting on nonfinancial factors since the late 1990s, and in the early days, many companies would issue reports just a few pages long. Today, an issuer’s ESG report is sometimes longer than its annual report, complete with explanations of the various best practices for all of the subsidiaries of the company.

In our survey, more investors said that company reports with “sector or industry-specific reporting criteria and key performance indicators” were “very beneficial,” more than with any other category of reporting. In second place was “statements and metrics on expected future performance and links to nonfinancial risks.”

Reporting on work in progress can be difficult for an issuer, especially in an environment where investors are focused on eliminating potential risks from their portfolios. Talking about objectives set in the future, rather than results and achievements already accomplished, can be risky for company managers because it’s possible the objectives won’t be met, or not met on time, Prudhomme says.

“If they fail, they fear that investors will react very negatively to the failures of not being able to achieve some environmental or social progress, according to their big plan,” he says. “We’re in a world that is more and more risk-averse. So if you consider that it’s a weakness for a company not to be able to achieve one of their objectives, you can see it can be difficult for the companies that prefer to control all their communication, especially when talking about ESG (plans).”

One ESG-related risk of particular concern to investors is stranded assets, due to changes in regulation, social expectations, disruptive technology or environmental conditions. More than 60% of survey respondents reported that they had either decreased their holdings within the last 12 months or were likely to monitor holdings closely in the future due to stranded asset risk (see figure 3).

With a company that is exposed to stranded asset risk, it’s often difficult for investors to know when that risk will become material to stock performance, says Edmond Schaff, head of selection for Cedrus Asset Management, a €200 million fund-of-funds manager in Paris.

As a policy, it’s easier for an investor to completely avoid, or underweight significantly, stocks exposed to stranded-asset risk, Schaff says, because the risk will inevitably be priced in by the market, but it’s difficult to know when it will happen.

Some institutional investors base buy, sell and pricing decisions on long-range financial models that calculate how specific environmental issues, such as climate change forcing switching to renewable energy sources, will affect certain sectors a decade or more in the future. For example, some investors sold out of their US coal investments before the overall decline in that market because their models predicted the downturn based on environmental concerns.

Regional differences: Is the world of ESG beginning to flatten?

Over the past three years, this research program has found notable distinctions in the views of investors across the principal geographies around the world. Readers of last year’s study will recall that investors in Europe and Australia led their peers in other regions in integrating a structured approach to ESG information analysis. Study respondents from North America were making gradual progress toward embracing ESG information in investment decision-making. And those in the Far East (excluding Australia) lagged behind the West in their use of nonfinancial information.

The results of this year’s study indicate that many of the regional differences we found around the world in prior years are flattening out.

Values vary across the regions in this year’s study, of course. But throughout the survey, the gaps between regions that were striking in prior years seem to be closing. Consider, for example, the use of a “structured, methodical approach to evaluating environmental and social impact statements and disclosures.” In 2015, 25% of respondents from the Americas reported using a highly structured approach, while 42% of those from Europe and 38% of those from Asia did so. Now, one year later, a similar 22% of respondents from the Americas say they use a highly structured approach, while the rates in Europe and Asia show a much more marked decline. Investors from Europe remain more likely to use a highly structured method for evaluating ESG information, but the gap between the respondents around the world has narrowed, now reflecting more consistent rates of adoption of methodical disclosures.

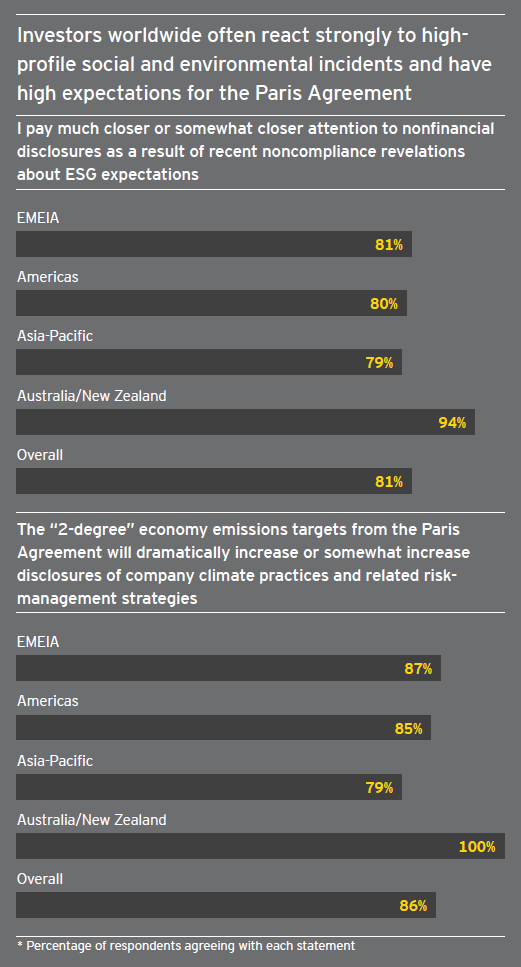

However, two examples from the 2016 survey illustrate differences in investors’ attitudes toward some parts of the most temporal and thematic questions in the study. Judging by the survey, recent scandals have driven investors in Australia and New Zealand to pay closer attention to ESG information, with 94% of the investors from that region—compared to 81% of investors as a whole—saying that they pay much closer or somewhat closer attention to nonfinancial disclosures as a result of recent noncompliance revelations. For investors in the Americas, 80% said they paid much closer or somewhat closer attention.

Similarly, 100% of the surveyed investors in Australia and New Zealand expected increased company climate practice disclosures as a result of the COP21 “2-degree” economy targets. Eighty-five percent of the Americas investors and 79% of the Asia-Pacific investors expected increased disclosures.

Why are investors from some regions more skeptical about the value of ESG factors in investment decision-making? One reason could be that investors are following commonly held regional beliefs or political views toward regulations—and environmental regulations especially. For years, the investment community often has perceived US investors as a whole as ESG skeptics and investors in Europe and Australia as the leading advocates of ESG investing.

For some US institutional investors, skepticism about the causes of global climate change—despite evidence supporting the causal relationship between carbon emissions and global warming—has limited the adoption of ESG factors in investment decision-making.

For example, the manager of a US$25 billion-plus state pension fund in the US—who asked not to be named—says that his investment decisions will have little to do with how well companies are complying with the goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, also known as COP21, or affecting climate change in general. That mindset—the skepticism about environmental factors having any value in investing—comes from his board and ultimately from the state’s legislators, who see it as their duty to follow the beliefs of their constituents. And for a state-directed pension board in New York or California, the political views that favor environmental concerns would probably hold sway, he says.

If investors reflect the generally held views of their regions, then one reason for different regional views could be the level of regulation in place, particularly with environmental regulations.

Institutional investors report that on the ESG reporting side, companies with operations in countries that already impose strict environmental regulations tend to be more advanced in their ESG practices and reporting. These companies are also a little farther ahead than their peers in implementing COP21-based goals.

It should be noted, however, that even in the Americas and Asia-Pacific, it appears an overwhelming majority of investors have high expectations for nonfinancial disclosures.

This survey also shows that the level of regional investor differences on ESG issues may be declining. For example, in 2015 and 2016, we asked investors how frequently a company’s nonfinancial performance had played a pivotal role in their investment decision-making in the last 12 months. As a whole, 27% percent of the investors answered “frequently,” 41% said “occasionally,” 27% said “seldom” and only 5% “never.” By region, investor views diverged from those averages, but the differences were smaller than in our 2015 survey, indicating that investors and their views are coming more into line across regions.

Declining levels of regional differences on ESG issues for investors could be attributed to several recent initiatives and events with global reach. In addition to the memo from BlackRock’s CEO, other examples include: the COP21 goals were enshrined in law by 195 nations and national agencies, such as the U.S. Department of Labor, and international groups like the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) are pushing for fiduciary duty standards to include consideration of ESG factors.

ESG skeptics often argue that fiduciary duty does not allow investors who are investing on behalf of clients to consider nonfinancial factors. But definitions and interpretations of fiduciary duty are changing in several countries.

The UN PRI issued a 2015 report, Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century, analyzing investment practices and how fiduciary duty is defined in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Japan, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. Among its conclusions, the report identifies “outdated perceptions about fiduciary duty and responsible investment” and in characterizing ESG issues, particularly in the US. The PRI report recommends that policymakers clarify that fiduciary duty should require investors to account for ESG issues in their investment decisions.

In 2016, the UN PRI also launched a three-year program to implement the core findings of its fiduciary duty report in the eight countries identified, to fully integrate ESG issues in investment policies and practices, and to make recommendations for clarifying fiduciary duties in China, India, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore.

Investors expect COP21 will 3 stimulate ESG reporting

Following the December 2015 Paris Climate Conference—also known as COP21, for the 21st meeting of the Conference of Parties—representatives of 195 nations have agreed to the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal that will limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial levels.

It will require the parties to achieve zero net carbon emissions globally by mid-century. The COP21 agreement will likely cause a significant shift in global economic policies, even beyond what was put forward by nations in Paris. It will reshape financial and economic markets toward zero emissions technologies, renewable energy sources and away from emissions-intensive products and services. Even if the challenging targets set out in Paris are met, companies will still likely be impacted by the physical impacts of a changing climate, and investors are increasingly asking them to set out how they’re adapting to the expected changes.

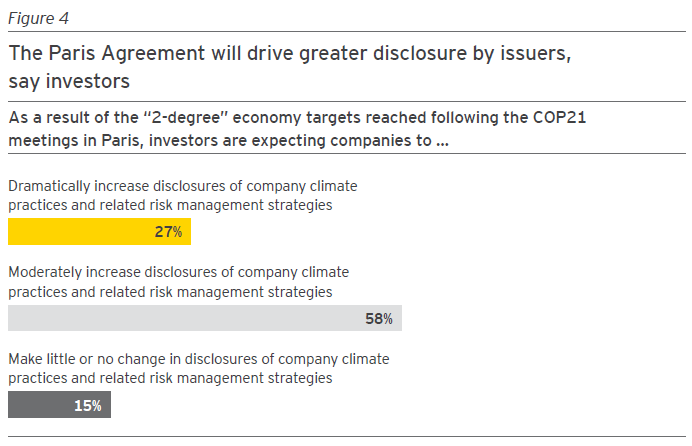

According to our poll of investors, 27% of all survey respondents expect COP21’s “below 2-degree” goals to lead to dramatically increased disclosures of company climate practices and related risk management strategies, with the majority (58%) expecting COP21 to moderately increase such disclosures. Just 15% of global investors expect little or no change in disclosures (see figure 4).

Following COP21, the key issue for investors is how to factor the transition to a lower-carbon economy into their analysis of ESG factors, says AMP Capital’s Kirkman. As the countries that signed off on the Paris Agreement pass their own laws and implement regulations, investors should discern which companies will be the winners and which will be the losers, and how companies will manage those risks and opportunities. Companies with operations in countries that already had strict environmental regulations prior to COP21 should be a little further ahead in adapting to the 2-degree economy.

Investors are often growing impatient with companies that aren’t adequately disclosing risks associated with the 2-degree economy, and a lot of companies are better geared for historical disclosures, after events happen, rather than forward-looking disclosures, Kirkman says. That’s leading to investors filing proxy resolutions to force disclosures of potential impacts, including potential stranded assets and unexploitable resources.

COP21 will likely lead to disruption for companies in the energy sector, and technology could accelerate the transitions, Kirkman says. Companies may think they have 10 to 15 years to adapt in situations where technology changes will give them only 6 to 8 years, for example.

Investors seem to be taking more action on climate change and carbon footprint risk than companies are—a movement that began before COP21 but gained traction after the Paris Agreement, says Edmond Schaff, head of selection for Cedrus Asset Management, the €200 million fund-of-funds manager in Paris. US investors seem to be taking more action on the divestment side—pensions and endowments simply selling their fossil-fuel-related positions, for example, he says—while in Europe more investors seem to be taking more nuanced approaches, such as “carbonizing” portfolios, or weighting investments according to carbon footprints, and engaging with companies on their carbon strategies.

Herve Duteil, corporate social responsibility coordinator for BNP Paribas in New York, says he has seen a dramatic change in companies—including business managers, executives and board members—in the aftermath of COP21, compared to the beginning of 2015. Besides raising awareness of climate issues in general, COP21 helped change the conversation from whether or not changes will come, to what can be done to adapt to the changes. That certainty should help companies in their planning. In the current environment, all investors, not just the largest institutional investors, will be more outspoken on the need for greater disclosure by issuers.

Until annual reports are released throughout 2017, it may be too early to tell what changes companies are making in the wake of the Paris Agreement, says BNP Paribas’ Prudhomme. The first companies to address the COP21 changes will be from the most exposed sectors, such as the oil and gas, mining, coal and chemicals sectors. Some companies in other sectors—including pharmaceuticals, agriculture, food and beverage and retail—have not yet revealed their exposure to climate change risk, but nearly all companies will be working on the issue.

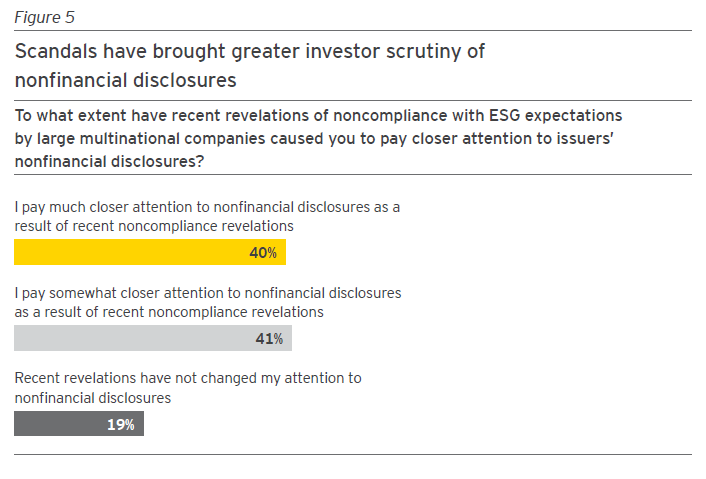

Recent scandals related to ESG issues have also drawn more attention to nonfinancial disclosures. When asked about recent scandals—noncompliance with ESG expectations—at large multinational companies, 40% of the investors in our survey reported that they paid much closer attention to issuers’ nonfinancial disclosures following the scandals, and 41% said they paid somewhat closer attention (see figure 5).

The recent case where it was discovered that software was installed so that cars may more readily pass emissions tests—was a prime example of a mainstream news story that drew attention to integrated ESG analysis by investors.

Our results show that investors are now paying closer attention to ESG disclosures and this serves as a cautionary tale that illustrates the value of ESG performance, and how poor governance or environmental practices can damage an investment. Companies involved may face paying significant sums to settle a class-action lawsuit, but the impact on shareholder value is likely to be much larger. These events also tend to encourage other companies to be more transparent with their own ESG information and put pressure on peer companies to prove that they don’t have similar problems.

Beyond COP21 and well-documented company environmental or social issues, several other recent initiatives promise to encourage improved reporting of ESG factors by companies and ESG interest from investors. In 2015, France passed a law making it the first country to require institutional investors and other financial firms to report on the carbon footprint of its investments, with mandatory reporting set to begin in June 2017. They also will have to report how they use ESG factors in their investment and risk management practices.

Another example is the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, chaired by Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City, which is developing voluntary climate-related financial disclosures for companies to use to provide better data to investors on climate-change risk. The task force offered its recommendations for public comment in December 2016, and the Financial Stability Board plans to present recommendations to G20 leaders in June 2017.

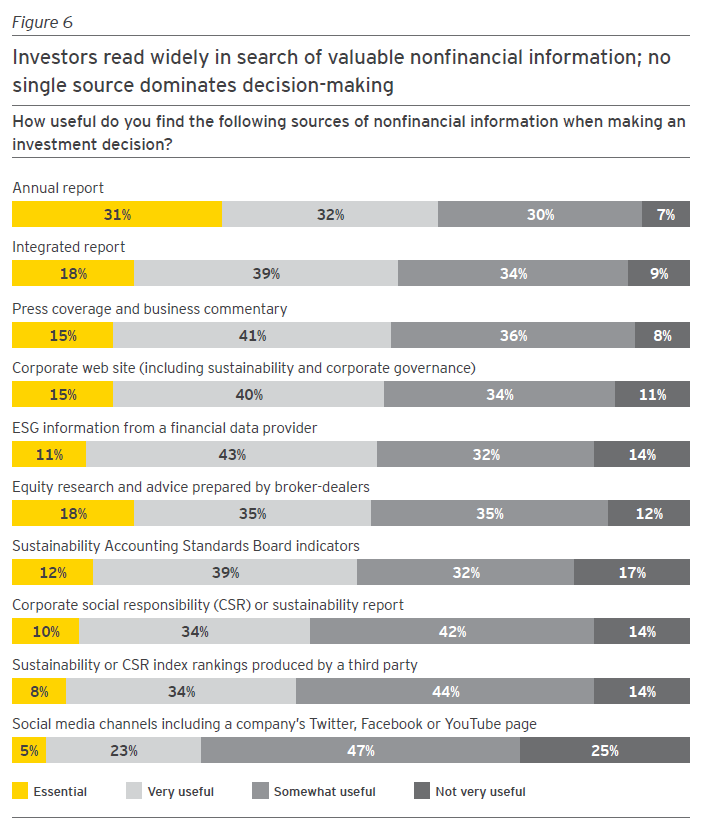

Investors demand more from company ESG reports

Surveyed investors reported that the most useful source of nonfinancial information for making investment decisions was a company’s own annual report—deemed “essential” by 31% of survey respondents and “very useful” by 32%. The second-most-useful source was an integrated report—“essential” for 18% and “very useful” for 39% (see figure 6).

While the annual report is held in highest regard for nonfinancial disclosures, most of the investors in our survey, 60%, believe that companies don’t disclose ESG risks that could affect their business and that they should disclose them more fully.

The quality of reported ESG information is getting better, with a range of research providers supplying more robust indicators and analysis, but there still is room for improvement, says AMP’s Kirkman. Large-cap multinational companies are getting better at ESG reporting, but the quality of reporting drops off significantly with medium- and small-cap companies. Investor stewardship codes for institutional investors in the UK, Switzerland, Malaysia, Japan and other countries will help drive better reporting on key ESG risks.

One appeal of the memo from BlackRock’s Fink, and its challenge to short-termism in the investing world, is that it could help refocus company reporting on medium- to long-term horizons rather than quarterly performance and hitting earnings estimates, Kirkman says. Some investors have even suggested that it may be time for companies to stop producing quarterly reports. This movement could be positive for integrating ESG factors in company reporting, because ESG reporting is naturally suited to a medium- and long-term focus on risks and opportunities, he says.

Related to both the quality and timeliness of reported information, it’s worth noting that corporate sustainability reports have yet to prove essential for investors. Despite broad support and widespread adoption of sustainability or CSR reports by companies in concept, this year’s survey suggests they aren’t delivering on their potential. Fewer than half of respondents (44%) view company sustainability reports as very useful or essential. An effective sustainability report—free from prevailing, short-term oriented financial reporting objectives—has the potential to widen the discussion to other sources of company capital (such as natural, social, human) with real impacts on perceived value. However, despite all of the public debate surrounding ethical conduct, climate change, modern slavery or globalization, we rarely see cases where outside stakeholders are pointing to CSR reports for reliable insight.

This year’s responses raise questions as to whether sustainability reports are too highly curated and too solution-oriented for investors. Rather than being a source of comfort for an organization, such reports, by nature, could create some discomfort. Otherwise, it becomes easy for the exercise to produce a mostly triumphant message, raising questions as to its longterm credibility.

Rather than having a company report on a shopping list of ESG indicators, Kirkman says he prefers the company to establish a core set of key risks and opportunities for its business, and to focus its reporting on those factors.

While the types of key ESG factors sought by investors varies by sector, governance is an overriding issue across companies. Environmental issues are also becoming more prominent, not only because of climate change issues, but because there is more data to work with than with social issues. Human rights issues will likely become more and more important as investors focus on the associated risk.

ESG disclosures are becoming more uniform across companies. But ESG reporting can be difficult for companies because investors are no longer satisfied with the standard list of indicators set by the Global Reporting Initiative organization, says Prudhomme of BNP Paribas. Investors often have their own individual requests for specific ESG information, and when companies can’t produce specific reports for specific audiences, investors are often left with a one-size-fits-all document.

“We are now entering a world where having the ESG performance indicators is useful, but not enough,” he says. “We really want to understand the strategy of the company, and how the company will manage its ESG risks.”

An example is with carbon footprint reporting, Prudhomme says. To the investor, it may be important to understand the various sources and amounts of carbon dioxide produced by a company, as well as the company’s explanation of its estimates for carbon pricing, how price is used and how various company projects will be affected. Companies are sometimes not well-equipped to provide price information, either because they consider it confidential or don’t have systems in place for a breakdown of their carbon-related capital expenditures.

Companies today are beginning to understand that the less they communicate on ESG factors, the more likely it is that they may be negatively rated by investors, Prudhomme says. They provide better access to investors because of this—a few years ago, companies would typically assign an investor relations staffer to respond to ESG inquiries, while today they are more likely to provide access to a relevant executive or department head, though they still typically want to maintain tight control over the information discussed.

The appeal of ESG analysis in risk management

One of the key benefits provided by ESG analysis for investors is risk avoidance and measurement. When asked if certain disclosures would make them change their investment plan, 39% of the investors in our survey said that a risk or history of poor governance would force them to rule out an investment immediately, while 32% said they would do the same due to human rights risk from operations and 20% said limited verification of data and claims would rule out an investment (see figure 7).

The top reason for reconsidering an investment, at 76% of survey respondents, was risk or history of poor environmental performance, followed by risk from resource scarcity at 75% and risk from climate change at 71%.

The surveyed investors reported using nonfinancial information fairly uniformly across all stages of their investment decision-making: examining industry dynamics and regulation, examining risk and timeframe, adjusting valuations to account for risk, making asset allocation and diversification decisions, and reviewing investment results. The examining industry stage had the greatest combined percentage of investors “usually considering” and “often considering” nonfinancial information.

The survey also showed that investors have high regard for board and audit committee oversight, which are typically viewed as keys to good corporate governance and risk management. Both mandatory board oversight and audit committee oversight were important to investors we surveyed: similar numbers said both types of oversight were “essential” or “very useful” (see figure 8).

ESG goals and preferences are evolving

The types of ESG information that investors seek have evolved from the early days of nonfinancial reporting, which some companies started as early as the 1990s.

Years ago, investors would often emphasize worker health and safety information from companies in heavy industry, such as the mining or oil and gas sectors, and liabilities associated with safety performance. Today, the information is still important, but companies release the information and manage the risk in the course of normal business, and the investors’ focus has shifted to other ESG issues, such as changing societal expectations, impacts of disruptive technologies, changing demographics, scarcity of water and other resources, climate change and post-financial-crisis executive pay.

Today, even information on cybersecurity risks can be associated with ESG disclosures: as a governance issue, from the angle of management and prevention of data leaks or hacking, and as a social issue because of the massive potential customer loyalty problems that could arise with a leak of private data to the public domain.

ESG information is also evolving as companies push out more raw data. For example, Bloomberg tracks and aggregates “total recordable incident frequency rates” for companies, counting the number of work-related injuries or incidents as a ratio of total hours worked by employees, derived from data reported to the U.S. Occupational Safety & Health Administration. Health and safety metrics also are often voluntarily reported by companies in their sustainability reports. Investors can use the numbers to help in the assessment of the strength of a company’s safety culture and incorporate them into their investment analysis.

ESG ratings have also evolved, now with nearly 100 firms supplying company ESG ratings. Morningstar and MSCI recently began supplying fund-level ESG metrics, and S&P has been more active in reporting on the fixed-income side. For large institutional investors, the value of more third-party providers of ESG ratings and information is that they cast a wider net, drawing attention to controversies or issues with specific securities. The investor’s own portfolio managers and analysts can then dive in deeper to determine how relevant the issue is, and whether it warrants discussion with company management, for example.

The way that investors use ESG information is also evolving. Where investors previously favored an approach that strictly separated the ESG and financial aspects of portfolio management, and with separate teams of analysts, now more investors are integrating ESG factors into their normal investment analysis, says Cedrus’ Schaff.

Investors are also taking a more in-depth view of risk and potential opportunities from ESG considerations.

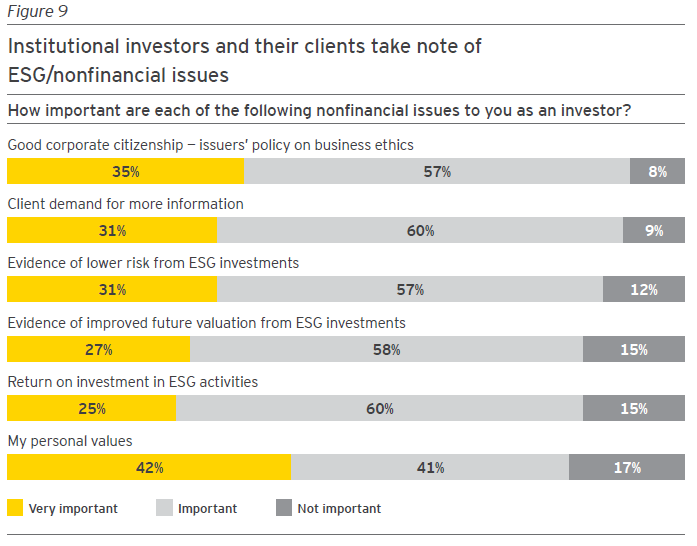

The most important nonfinancial issue for investors in the survey was in relation to “good corporate citizenship and issuers’ policies on business ethics,” with 35% of respondents calling the issue “very important” and 57% saying it was “important” (see figure 9). Client demand for more information was nearly on the same level, with 31% calling it “very important” and 60% “important.”

Over the last 12 months, 27% of the surveyed investors said a company’s nonfinancial performance had frequently played a pivotal role in their investment decisions. For 41% of the survey respondents, nonfinancial performance occasionally played a pivotal role, and for 27%, the nonfinancial performance seldom played a pivotal role.

Given that nonfinancial performance periodically played pivotal roles in their investment decisions, a surprisingly small percentage of the investors in our survey reported that they conduct structured reviews of environmental and social factors. Of the surveyed investors, 51%, said that their evaluation of environmental and social impact statements and disclosures was informal. That compared to 26% who said their evaluation was structured and methodical, and 22% who conducted little or no review.

When asked why they don’t consider nonfinancial issues in their investment decision-making, 42% of the surveyed investors answering the question said that nonfinancial measurements are seldom available for comparison with other companies, and the same number said the information is often inconsistent, unavailable or not verified (see figure 10). Only 16% said that nonfinancial disclosures seldom have a financial impact or are material.

For the manager of a US$25 billion-plus state pension fund in the US—who asked not to be named—ESG factors aren’t considered because they limit his investment options.

“You have a lot of people running around now saying that it’s actually a positive predictor, and you can put all of these ESG factors in, and you’ll actually do better than you would have otherwise, and I think that’s kind of neat packaging, and if it really works, then everyone on (Wall Street) will want to do that,” he said. “And (Wall Street traders) don’t, so I’m always kind of concerned about that.”

As discussed in a prior section on geographic variables, the evolving fiduciary duty definition will likely have a broad impact on ESG reporting and further shape the perception of using nonfinancial factors in investment decisions. ESG skeptics often argue that using nonfinancial information to help make investment decisions can violate an investment manager’s fiduciary duty.

But the U.S. Department of Labor has helped legitimize the use of ESG factors in fiduciary investment decisions. In October 2015, the Department of Labor issued new guidance for retirement plans that stated that ESG factors “may have a direct relationship to the economic and financial value of an investment,” and that when they do, a fiduciary can use them in analyzing an investment.

The evolution toward integrated ESG investment analysis serves to support the use of such factors by fiduciaries, says Cedrus’ Schaff.

“If you take this integrated approach, it’s even easier to be aligned with fiduciary duty of the portfolio manager, because it leads you to look at a broader set of risk and opportunities, larger than what you can derive from financial data, like the balance sheet,” he says. “Hence, it helps you to have a more comprehensive view of the company, and probably to perform your fiduciary duty even better.”

What next?

With institutional investors using nonfinancial information more often in their decision-making, what should reporters do next?

We believe the actions split into three main areas:

- Meet your investors’ and prospective investors’ expectations

- Seize the opportunities to tell your organization’s performance story

- Address the essentials

Meet investor expectations

- Take a long-term view. Meet investor needs by informing them of the most material environmental, social and economic aspects that could impact your company’s ability to generate value over the longer-term—and what steps you are taking to manage them.

- Consider the global megatrends. Understand what could be shaping and disrupting your industry over the coming decades. Balance current risks with future opportunities to show investors your business model is future-fit.

- Address climate risks. With a legal framework to decarbonize the global economy by mid-century, investors expect you to significantly rethink your climate disclosures. Not only will you be expected to report on the direct impacts of your business on greenhouse gas emissions, you’ll also likely be required to articulate the potential physical impacts of climate change on your assets and supply chain, and how your current business model will be sustained in a zero carbon future.

- Allocate capital and infrastructure to ESG. Investors agree that environmental and social aspects of performance are fundamentally important and for too long have been overlooked. Evaluate the adequacy of your allocated capital to put processes and procedures in place to address ESG issues and regulations

Seize the opportunities

- Trust the evidence. Academic research now reveals that companies with strong sustainability performance outperform their peers, and the market in general. Investing in understanding the opportunities of managing environmental and social risk could pay dividends.

- Set the agenda. Investors understand just how important ESG information is to your business’s performance but still largely review this information and data informally. This provides an opportunity for your company to lead the way in highlighting your understanding and management of the risks and opportunities you face.

- Engage your stakeholders. Involve a broad cross-section of your stakeholders in determining what aspects of your business are of most importance and keep them informed on progress.

- Engage your board. Investors tell us they expect the board to have signed off on your strategy and disclosures. Engaging the board in the process early should provide the governance expected of you, and minimize the likelihood of heading in a direction inconsistent with their expectations.

- Connect your reporting. Consider how you can make your reporting more connected, or integrated. This will seek to avoid the risk of producing disparate reporting that doesn’t align or, at worst, creates contradicting disclosures.

Address the essentials

- Materiality matters. Avoid being seen as “green washing” in your sustainability disclosures by applying a robust materiality process. A well-considered report should be able to articulate the environmental, economic and social risks and the opportunities most important to your stakeholders, and the ability of these risks and opportunities to impact your business now and into the future. Focusing on the positive, but ultimately less material aspects, may undermine your credibility with readers.

- Be transparent. Investment decisions are being made on the ESG performance of your business whether you report on them or not. Transparency on challenges you face, and how you are managing them, will be more beneficial than producing a report that just highlights the positive aspects of your performance. Reporting on ESG aspects should also be a challenging process. If not, you should question whether you’re actually telling investors something they don’t already know.

- Value third-party assurance. Having independent verification as part of your reporting process is important, as over two-thirds of all investors say it is very useful or essential. Coverage of material issues, data and information will add significantly to the credibility of your reporting not just with investors, but all stakeholders.

The complete publication is available here.

Endnotes

1The study from Oxford University and Arabesque Asset Management appears at the following URL: http://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/research-projects/MiB/4-Arabesque-Case-Narrative.pdf(go back)

2Deutsche Bank’s 2012 report, “Sustainable Investing: Establishing Long-Term Value and Performance,” appears at this URL: https://institutional.deutscheam.com/content/_media/Sustainable_Investing_2012.pdf(go back)

3RG Eccles, I Ioannou, S Serafeim; The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance; Harvard Business School Working Paper; 2012.(go back)

Print

Print