Paula Loop is Leader of the Governance Insights Center at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. This post is based on a PwC publication by Ms. Loop.

Focusing on growth is a given when it comes to increasing value for a company’s investors. That can mean exploring an acquisition or a strategic alliance—actions that expand the organization’s reach. But a divestiture could also help boost returns for shareholders. In fact, many shareholder activism campaigns have urged selling parts of companies as a way to unlock value.

Why is that? Some companies have businesses that don’t contribute to core capabilities or fit with their current strategy, or whose financial performance lags other businesses and are a drag on earnings. By removing the nonconforming businesses, a company can create a more focused portfolio for shareholders. A divestiture also can enable a business that doesn’t fit to potentially thrive elsewhere—either on its own or as part of another company.

Recent corporate breakups across industries indicate that management teams are actively reviewing their business portfolios with a critical eye. Any potential divestiture should be aligned with a company’s overall strategy and plans to create long-term value. Boards that show they understand this strategy and how each part of the company does or doesn’t contribute to it can instill more confidence in shareholders.

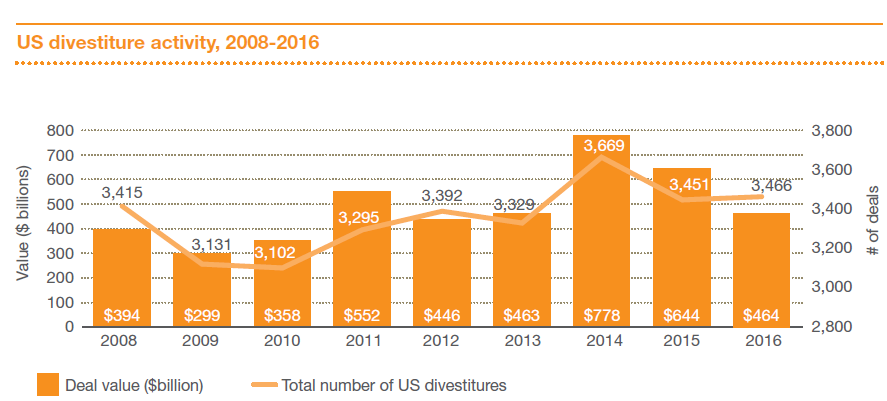

Note: All deals over $100 billion have been excluded from the analysis above. Source: Thomson Reuters, with PwC analysis.

Divestitures can be challenging. A company must identify the business units to be separated, decide on the type of separation and either develop a standalone operating model and cost structure for that business or prepare it for sale. While these steps may seem straightforward, a divestiture ultimately is a surgical procedure, with a degree of complexity that demands careful planning and caution.

When a company has identified a business or division that doesn’t fit its overall strategy or could pursue new opportunities as a separate entity, it raises important questions for the board.

- What is the goal of the divestiture?

- What kind of divestiture should we consider?

- How important is timing?

- How are we handling talent?

- What should our board watch out for after a deal is done?

What is the goal of the divestiture?

The reasons for removing part of a company can vary. In some cases, management may see the need to fix something. Previously acquired companies may not have been integrated successfully, or an older business unit might not align with a new company strategy or the direction of new leadership.

A company also could see an opportunity through a divestiture. A thriving business may have outgrown the parent company and be ready to chart its own course with its own management and board. Individual parts of an enterprise could be more valuable as separate businesses or part of another company, particularly if one or more of them have become successful brands. Or a company may divest a business so it can reinvest the proceeds in the remaining company or pursue growth opportunities, including acquisitions.

Regardless, a company’s rationale for a divestiture should be strategic, clear and compelling, and one the board fully understands and endorses. One simple question directors can ask is if and how removing a business unit will allow the company to do something it can’t do today.

This could mean a blunt assessment of how the company is limited or inefficient in some way. Giving a business unit financial, operational and strategic independence should result in the divesting company being in a more profitable position.

Divestitures can allow companies to accomplish a variety of strategic and other goals:

- Boost valuation—generate cash to repay debt obligations, meet debt covenants, do stock buybacks, fund working capital needs or simply “cash out” of an investment.

- Focus on the core business—remove non-essential divisions so management and employees can better focus on the company’s overall strategy.

- Fund growth—secure funding for acquisitions, significant capital expenditures or innovation, or to reinvest in the company for organic growth.

- Lower the tax burden—generate significant tax savings and ultimately cash inflow for the businesses; this might mean selling at a loss to gain tax advantages.

- Mitigate risks—remove divisions, products or services that have damaged or could damage the company’s brand and impact profitability

- Optimize assets and operations—use joint ventures to combine assets with partners to generate synergies on lower performing assets, or as a staged divestiture to improve divisions and sell them later.

- Pursue future deals more efficiently—capture buyer opportunities as they become available or limit value leakage and deal deterioration over an extended period.

What kind of divestiture should we consider?

Companies have multiple options for divesting a business unit and may choose to either maintain some type of connection with the divested unit or sever all ties. Depending on the exit structure and approach, the regulatory, tax and reporting requirements can vary significantly and usually involve different timetables.

In a carve-out IPO, a company separates a business unit or subsidiary but offers only a minority interest in the new entity to outside investors. The result is two separate legal entities, each with its own financial statements, management team and board of directors. But the parent company retains a controlling interest in the new company, which allows the parent to provide strategic support and resources. The parent company may want to continue to capitalize on the carve-out company, even if it isn’t part of its core operations. The parent also may want to gauge investors’ appetite in the new entity before it considers making more or the rest of its stake available to the public.

A spin-off creates an independent company with its own equity structure, with shares in the new company typically distributed to the parent company’s shareholders. Unlike a carve-out IPO, the parent company doesn’t have a controlling interest and instead holds no equity or possibly a minority stake. This allows the parent company to focus on its strategic long-term goals. A spin-off may not change the overall value held by the parent company’s shareholders, but the newly-independent business may gain new opportunities to access capital or pursue its own deals and growth strategy. In addition, although spin-offs generally are structured as tax-free to both the parent company and its shareholders, the parent company can still monetize part of its investment.

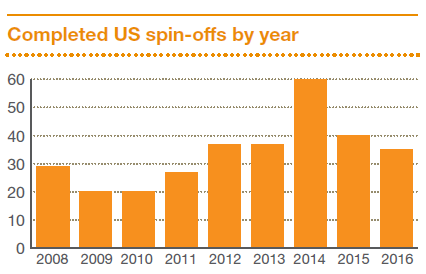

Source: Spin-Off Research

A split-off is similar to a spin-off in that it also creates a new entity with its own equity structure, and the parent company doesn’t have a controlling interest. The difference is that shareholders can essentially exchange shares in the parent company for shares in the new company. Shareholders choose whether to participate in the split-off by swapping some or all of their parent company stock for subsidiary stock. How shares are distributed distinguishes a split-off from a spin-off. The former can have a less dilutive effect than the latter on the parent company’s earnings per share. As motivation to exchange their shares, parent company shareholders may be offered shares in the new company that are worth slightly more than the parent company shares.

“Many companies pride themselves on their ability to use acquisitions to drive inorganic growth. It’s far more rare to find a company that prides itself on the way it divests a business or asset.”

—“The Secret to a Successful Divestiture,” Aug. 27, 2013, strategy+business (originally published by Booz & Company)

A parent company may contribute a portion of its business to form a joint venture (JV), with or without control. These transactions can unlock synergies with a partner and provide access to other assets when other transactions may not be available. They require continuing involvement over the life of the JV and significant financial, operational and reporting considerations in structuring the JV. (For board considerations when management is considering an alliance, see Building successful alliances and joint ventures).

A trade sale typically is the cleanest type of divestiture, with a company completely turning over a subsidiary or business unit to another company, a private equity firm or some other buyer. Although a sale may be easier and faster to complete than the other types of transactions, the parent company’s gains from selling the subsidiary or business unit usually are subject to taxes. The need to prepare financial statements is primarily driven by the buyer’s due diligence, financing or SEC reporting requirements.

Selling to focus on core businesses

When financial software company Intuit decided to focus its organization on core businesses, it faced the daunting challenge of selling three business units. The company wanted to conduct those divestitures simultaneously so it could minimize ongoing obligations and distractions to employees and the remaining businesses.

Just one divestiture can require significant time and effort, and multiple divestitures often demand personnel and other resources that a company may not have in-house. In this case, Intuit needed expertise in preparing a product technology separation while reducing business and employee disruption.

With PwC’s help, the company was able to define the scope and parameters of separation plans and transition service agreements early on and manage risks and other issues across more than a dozen work streams. As a result, Intuit was able to divest all three business units within three months of each other for a combined total of roughly $500 million.

How important is timing?

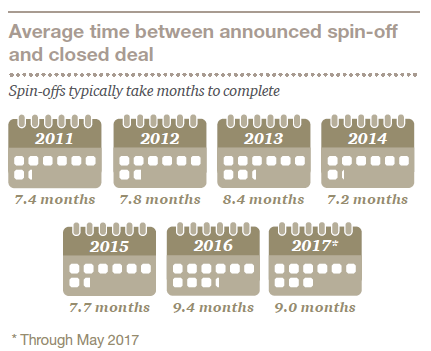

Timing is an important consideration in any discussion about a potential divestiture. Different types of divestitures typically take different lengths of time to complete. That matters if a company needs to separate a business quickly—because of broader company concerns, market issues or some other reason.

A sale usually takes the least amount of time—anywhere from a few months to a year. If a company needs to secure capital, reduce expenses or make some other financial or strategic move in the short term, it may be limited to contemplating a sale because other deals would take too long.

While a sale may not be as complex as other divestitures, it still raises key considerations for the board—notably, how to maximize value for shareholders. Management should tell directors if there’s a specific buyer in mind or if the business unit will be marketed to a wide range of possible buyers—and if the latter, how and to whom. Private equity buyers may have different requirements or conditions than corporate buyers. If the potential buyer is another company, the board should know if it’s in the same industry and be able to share any concerns it might have with management. That might include challenging management on whether the company is comfortable totally giving up the business in question instead of maintaining a relationship through another type of divestiture.

Carve-out IPOs, spin-offs, split-offs and JVs take longer to finalize—sometimes more than a year. As in a sale, there’s the work of separating the business unit from the parent company’s operational and financial infrastructure. But forming a new entity involves legal, regulatory and other requirements that simply selling a business to a buyer doesn’t. And, depending on the industry, it may require regulatory approvals, which can take time.

How companies figured out which piece didn’t fit

Divesting a part of a company is like surgery. Knowing where to cut often requires a thorough assessment of the entire portfolio of businesses, often aided by advanced analytics.

For instance, one US-based global manufacturer determined that pursuing its corporate strategy would mean divesting of businesses in other countries. Over a year, the company developed a strategy for a non-core business as a standalone operation and leveraged its relationships with potential buyers to conduct an international auction.

The auction generated broad interest, and the sale price ultimately exceeded expectations.

Creating a separate company takes time

Carve-out IPOs, spin-offs, split-offs and JVs usually are more complex and take more time than selling a business unit outright. The requirements to have the new entity ready on Day One include:

- Creating standalone financial statements and fulfilling regulatory reporting obligations

- Responding to due diligence requests.

- Determining tax structuring.

- Deciding the organizational design, operating model, business processes and IT systems.

- Separating operations from the parent company and negotiating transition service agreements

This investment of time, money and energy usually is significant and can test management, especially if a company is already lean. Without adequate resources, the transaction could become a distraction that affects day-to-day operations—something the board should be aware of and discuss with management ahead of time.

Before the company embarks on a divestiture spanning several months, directors should ensure management has or will hire the right people to handle the heavy lifting. The board also should be confident in management’s plan to keep the remaining businesses running effectively and employees engaged in their work.

Source: PwC analysis

How are we handling talent?

Depending on the type of divestiture, talent can be a relatively small issue or a more complex concern. In a sale, the employees and leaders in the business unit often stay in their existing roles as the business moves to new ownership. But the divesting company may want to retain certain talent, such as executives with senior leadership potential. Board members should be aware of those conversations and make sure such pursuits don’t jeopardize the transaction. Once the sale is completed, however, personnel and development issues at the business in question are matters for the new owner.

Talent decisions are typically more complicated with carve-out IPOs, spin-offs, split-offs and JVs. Because parent company shareholders still have some level of investment in the new entity, boards should have a stronger interest in decisions about employees and leaders. Shareholders would likely be concerned if a company went to the trouble to create a separate business and then left the operations and management to a subpar team.

Strong leaders are essential for both entities during and after the separation. The board should ask management if the managers of the business unit being separated are willing and able to lead an independent company. If not, directors should ensure that management has built a deep enough talent bench within the company or is willing to bring in new talent. Ultimately, management must be prepared to establish a capable and credible executive team at the separate entity.

Talent migration is complex, particularly for employees working outside the separating business unit, such as finance or IT. While people attached to the divested business can expect to be affected, the transaction also could pull employees from these enterprise functions, and management needs to be strategic about who stays and who goes.

It’s common for employees in these functions to question management’s decision to shift their employment to the new entity, and some could choose to leave for new jobs elsewhere. To influence those decisions, management may offer compensation, career development opportunities and other incentives, such as stay bonuses. Management will also have to address deferred compensation for the individuals who are going to the new entity. These measures also can assure the buyer that talent remains strong and facilitate a smooth transition. The parent company board should ensure that leaders are equipped to communicate the rationale behind talent decisions.

Tackling these issues early will help prevent scrambling to fill key positions later. Understanding at the start of the process where talent gaps will exist—both in the parent and separating companies—provides for more time to plan for the necessary incremental hiring from outside the companies.

A divestiture also can affect employees and managers who aren’t directly involved in the transaction. Any uncertainty about the parent company’s future after the divestiture could raise questions among the remaining talent and cause them to consider other opportunities. The board should confirm that management is keeping the entire company in mind and has a comprehensive communications plan for the entire deal cycle.

Transition service agreements

In some divestitures, a transition service agreement (TSA) requires the seller of a business to provide certain services and support for a certain period after the deal closes.

Divestitures can be tricky to pull off, particularly when the affected people, processes and systems are deeply integrated within the seller’s business, or when services and infrastructure are shared across multiple business units. In such scenarios, a TSA is increasingly important to help the buyer and seller agree on how to achieve a clean and fast separation and to stay focused on priorities for closing the transaction.

A TSA may require the seller to plan for the costs of essential services in various functional areas for the business that is being divested. These services might include finance and accounting, human resources(HR), legal, information technology (IT), procurement and other services.

The objective is to ensure business continuity while the new company establishes its own internal capabilities or to transition these services to a third-party vendor.

A divestiture involving a TSA may require the seller to plan for the costs of these services, particularly if they’re the result of fixed assets or contracts that can’t be renegotiated. These costs can last from a few months to more than a year. Once the seller completes its TSA obligations, it may downsize the relevant functions, which could result in severance payments to exiting employees.

These costs can affect the overall transaction value, particularly in jurisdictions with generous severance practices, and they should be estimated during early divestiture planning. Depending on the type of divestiture, these costs could affect negotiations between the buyer and seller, as well as the purchase price or cost of the TSA.

What should our board watch out for after a deal is done?

A divestiture can be an opportunity for a company to more aggressively pursue its strategic priorities. But a successful divestiture means going beyond executing the details of the transaction and taking the necessary legal steps to separate a business from the company. It requires putting both companies on the right trajectory for profitability and growth in the years following the deal.

This means striking the right balance when it comes to changes post-deal. If the new entity and parent company make only slight adjustments in strategy and operations, they run the risk of simply being smaller versions of the formerly combined company, with stranded costs and few, if any, new advantages. But if the two entities make drastic shifts, it could make the divestiture process even more complex and overwhelm the companies, leaving them fumbling as they set off in separate directions. The board can help with this balance by engaging management on the divestiture plan and, if it’s not a full sale, ensuring that it will leave both companies in competitive market positions.

In some divestitures, accounting, legal, tax, IT or other important services may not go with the subsidiary, leaving the parent with more employees or capacity than it needs. The parent company will have to determine how to deal with the resulting stranded costs or overhead. One way is through a TSA—sellers should negotiate an early termination notification period that allows sufficient time for them to handle stranded costs before the service agreement ends.

One short-term challenge for the new entity after the transaction closes is the cost of establishing and managing processes and personnel that had been covered by the parent company. If the new entity had been tightly integrated with the parent company, those costs could be high—especially in the early months, before profit growth can offset the expense. The board should make sure there’s a cost-mitigation plan in place before the split. That plan shouldn’t be simply copied from the parent company, nor should it be overly aggressive, which may hamper the new entity’s operations.

The board also can help shareholders in the carve-out IPO, spin-off, split-off or JV understand how those added costs ultimately will be offset over time. Maintaining focus on the value being created through the divestiture against the short-term costs is vital for shareholder confidence. Directors should understand how the divestiture may create opportunities for long-term value in both companies—whether it’s exiting an unprofitable line of business, making major capability enhancements or even changing a culture.

Also keep in mind the impact of a divestiture on the original company—namely to groups that support the enterprise. Large divestitures can leave the remaining company with more personnel than needed in such areas as HR, legal, IT, compliance and others. The board should discuss with management if the company will need to restructure to stop paying for services that are no longer needed.

Finally, the board should consult with management on whether the divestiture process could make the company vulnerable to competitors. With highly visible and/or complex separations, other companies could see an opportunity to disrupt customer relationships and grab market share. Management should explain to the board how the company is prepared to handle any such attacks and how they will provide business as usual for customers.

From one board to two

If a new company is created through a carve-out IPO, spin-off, split-off or JV, it will need its own board of directors. The parent company board and management should collaborate on a recommendation for that new board, including its structure and how much the new entity’s governance policies should align with those of the parent company.

In some cases, creating a new company board could affect the parent company’s board. Depending on the focus of the new entity, it could make sense for some of the parent company’s directors to join the new entity’s board.

As for the remaining company, if the divestiture significantly reduces its size or changes its strategic direction, the board composition may need to shrink. Regardless of the scenario, the challenge of ensuring you have the right board members

remains constant.

In conclusion…

Done right, a divestiture can maximize shareholder value for all companies involved. Divestitures aren’t just a tool for removing a piece of your company. Whether it provides capital through the sale of a business or carves out a subsidiary that can pursue its own opportunities, a divestiture can generate significant value for a company’s shareholders.

Boards can provide guidance at different stages of these complex transactions. With the right understanding and planning, companies that are considering a divestiture in a dynamic market can achieve strategic goals and ultimately deliver greater value for their shareholders.

Print

Print