Stephan Hollander is Professor of Financial Accounting at Tilburg University. This post is based on a recent paper by Professor Hollander; Tarek A. Hassan, Associate Professor of Economics at Boston University; Laurence van Lent, Professor of Accounting and Economics at Frankfurt School of Finance and Management; Ahmed Tahoun, Assistant Professor of Accounting at London Business School.

From the UK’s vote to leave the European Union to the threats of the US Congress to shut down the federal government, recent events have renewed concerns about the effects of risks emanating from the political system on investment, employment, and other aspects of firm behavior. The size of such effects, and the question of which aspects of political decision-making might be most disruptive to business are the subject of intense debates among economists, business leaders, and politicians. However, quantifying the effects of political risk has often proven difficult due to a lack of firm-level data on the extent of exposure to political risk, as well as a lack of data on the kind of political issues firms may be most concerned about.

In our paper, we use textual analysis of quarterly earnings conference-call transcripts to construct a firm-level measure of the extent and type of political risk faced by individual firms listed in the United States. The vast majority of firms with a listing on a US stock exchange hold regular conference calls with their analysts and other interested parties, a forum where management gives its view on the firm’s past and future performance and responds to questions by call participants about any challenges the firm may face. Our approach to quantifying the extent of political risk faced by a given firm at a given point in time is simply to measure the share of the conversation between participants and firm management that centers on risks associated with politics in general, and with specific political topics.

To this end, we adapt a simple pattern-based sequence-classification method developed in computational linguistics to distinguish between language associated with political versus non-political topics. [1] For our baseline measure of overall exposure to political risk, we use a training library of political text (an undergraduate political science textbook or text from the political section of newspapers) and a training library of non-political text (an accounting textbook, text from non-political sections of newspapers, or transcripts of speeches on non-political topics) to identify two-word combinations (“bigrams”) that are frequently used in political texts. We then count the number of instances in which conference-call participants use these bigrams in conjunction with synonyms for “risk” or “uncertainty,” and divide by the total length of the conference call to obtain a measure—which we dub PRiskit—of the share of the conversation that is concerned with risks associated with politics.

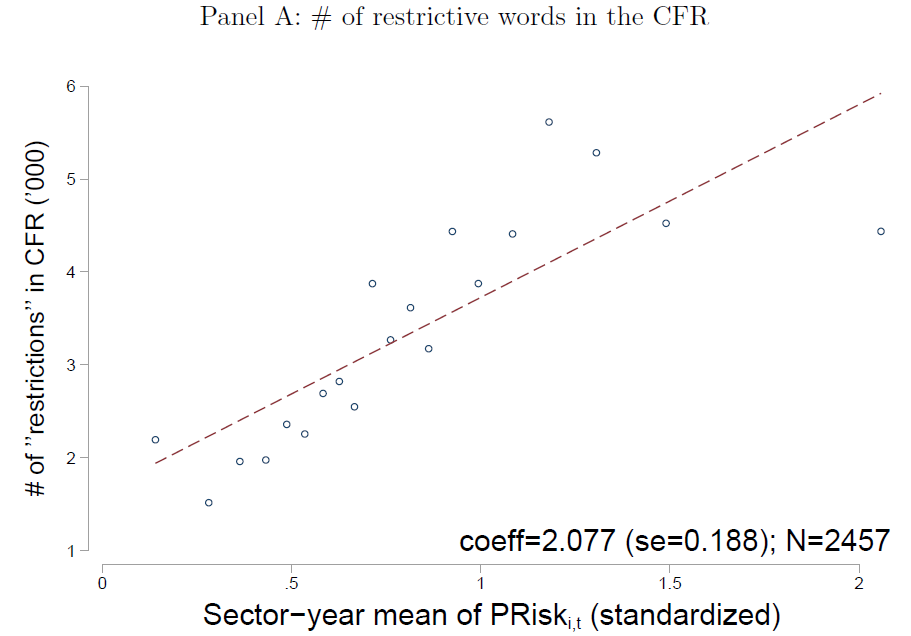

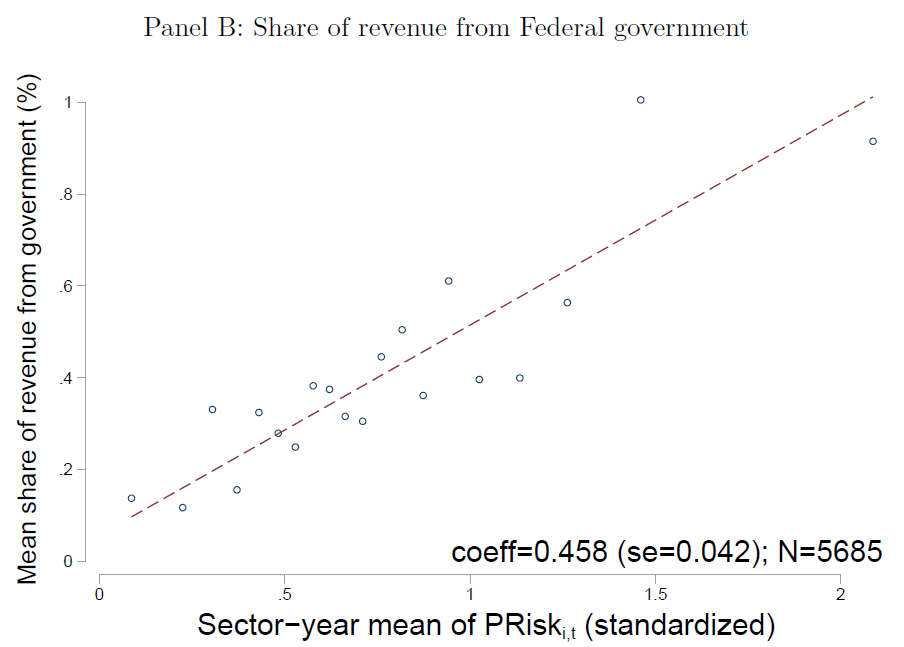

We conduct a range of tests to show that our measure indeed reflects meaningful firm-level variation in exposure to political risk. For example, Figure 1 shows that the mean of PRiskit across firms in a given 2-digit SIC sector is highly correlated with a sector-level index of regulatory constraints [2] (panel A), and with the share of the sector’s revenue accounted for by federal government contracts (panel B). Overall, these means line up intuitively with parts of the economy most dependent on government for regulation or expenditure.

Figure 1: PRiskit and sector exposure to politics

Similarly, other tests show PRiskit correlates strongly with the firm’s stock market volatility and with firm actions—such as hiring, investment, lobbying, and donations to politicians—in a way that is highly indicative of political risk. [3]

Interestingly, we find the incidence of political risk across firms is far more heterogeneous and volatile than previously thought. The vast majority of the variation in our measure is at the firm level rather than at the aggregate or sector level, in the sense that it is neither captured by time fixed effects and the interaction of sector and time fixed effects, nor by heterogeneous exposure of individual firms to aggregate political risk. In this sense, firms considering their political risk may well be more worried about their relative position in the cross-sectional distribution of political risk (for example drawing the attention of regulators to their firms’ activities) than about time-series variation in aggregate political risk.

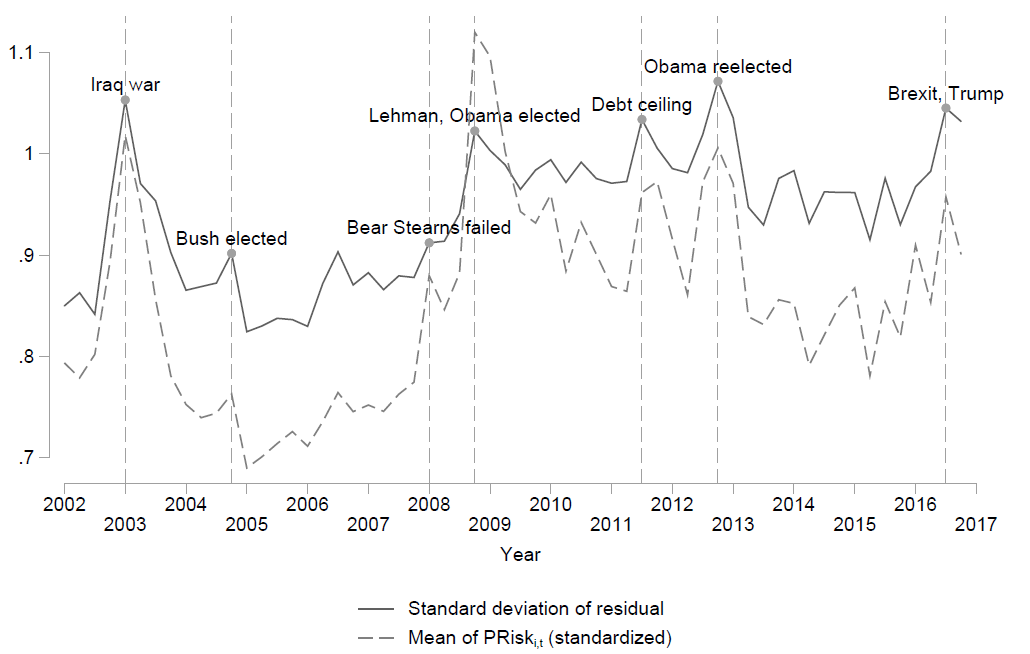

Figure 2: Dispersion of PRiskit over time

A direct implication of these results is that the effectiveness of political decision-making may have important macroeconomic effects, not only by affecting aggregate political risk, but also by altering the identity of firms affected by political risk and the dispersion of political risk across firms. As shown in Figure 2, the dispersion of this firm-level political risk increases significantly at times with high aggregate political risk.

Decomposing our measure of political risk by topic, we find that firms that devote more time to discussing risks associated with a given political topic tend to increase lobbying on that topic, but not on other topics, in the following quarter.

The complete paper is available here.

Endnotes

1Manning, C., P. Raghavan, and H. Schűtze, 2008. Introduction to information retrieval. Cambridge University Press.(go back)

2Al-Ubaydli, O., and P. A. McLaughlin, 2017. RegData: A numerical database on industry-specific regulations for all United States industries and federal regulations, 1997-2012. Regulation & Governance 11: 109-123.(go back)

3Baker, S., N. Bloom, and S. Davis, 2016. Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 1593-1636.(go back)

Print

Print