Dan Marcec is Director of Content at Equilar, Inc. This post is based on an Equilar publication by Mr. Marcec; research analysts Kyle Benelli, Sean Barry, and Angelo Martinez contributed data analysis to the study.

A wave of lawsuits surrounding director compensation surfaced a couple of years ago, often alleging “excessive” pay for boards of directors on a variety of grounds. Because boards set their own pay levels, there are potential legal ramifications due to the “self-dealing” nature of director compensation. While lawsuits were settled and subsequent litigation has subsided, the topic is back in the spotlight in light of the updated Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) proxy voting guidelines.

In a recent webinar hosted by Equilar and Meridian Compensation Partners, Michael Falk, a partner with law firm Kirkland & Ellis set the stage. “We are seeing a trend now that corporations will put a ‘meaningful limit’ into their director compensation plan if it’s not in there already,” he said. “These lawsuits showed that you want to have a separate limit that is specific to directors, proposing that the board will pay no more than a certain value transferred to directors in any one year in combined cash and equity.”

In an example of limits working in a corporate issuer’s favor, the Delaware Chancery Court dismissed a case brought against Investors Bancorp for alleged excessive director pay in April of 2017 explicitly because shareholders had approved its equity incentive plan that contained director-specific limits on awards. The grants made to the Investors Bancorp board totaled about $2 million per director, which came in under the shareholder approved limit.

“[The Investors Bancorp case] was challenged, but because the plan had that limit in there, even though it was rich, the company prevailed,” said Falk. “This issue has more visibility, and if you have not done it, you should be thinking about what limit should be separate and distinct and applies only to directors.”

According to the recent Equilar report, Director Pay Trends, the median base retainer for Equilar 500 companies was $245,000 in fiscal year 2016. Therefore, limits would land in the $500,000 to $750,000 range if they are following the typical trend of a 2-3x multiple.

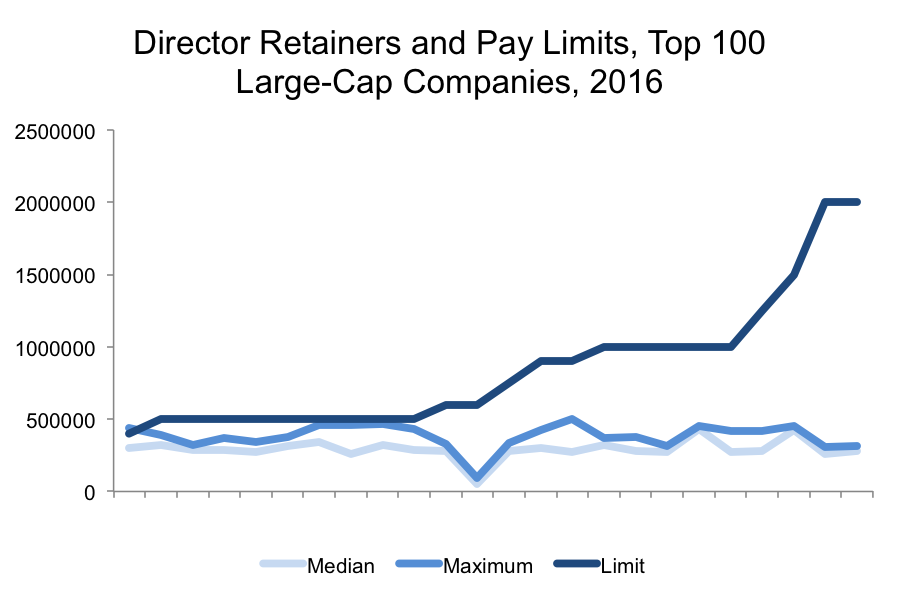

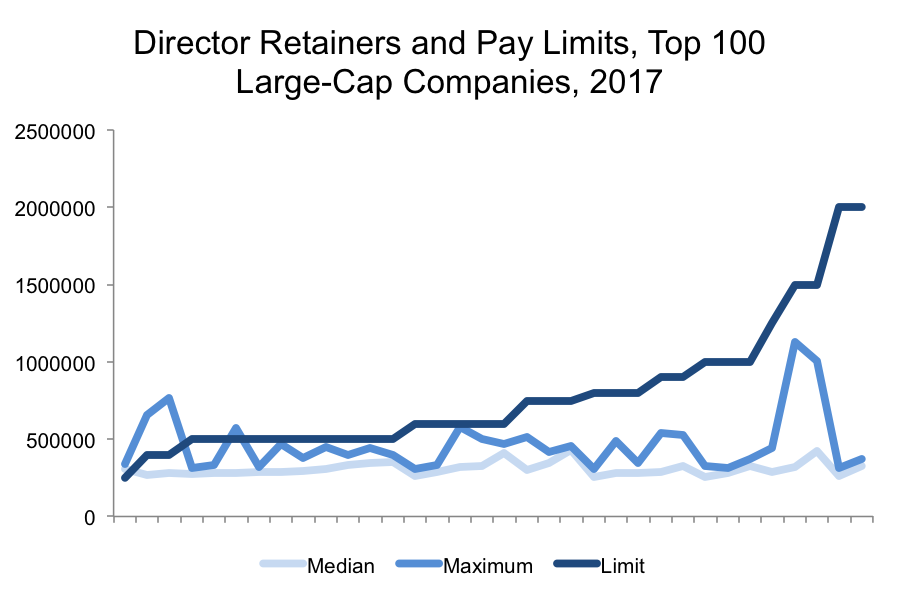

An Equilar study of 100 large-cap U.S. companies [1] found that 34 of them disclosed director pay limits in 2017, vs. 24 in 2016. Key data points from the two charts that follow are below:

- The median director retainer for those 34 companies in 2017 was $292,498, and indeed, the median cap was $600,000, just over 2x.

- For the 24 companies that disclosed a limit in 2016, median retainer was $283,497 and the median cap was $675,000.

- The average gap between limits and median pay was $447,345 in 2017, down from $558,183 from the year prior—suggesting that limits put in place in 2017 were lower than the those already existing.

- However, in 2017, four companies had maximum director retainers that exceeded the stated limit, vs. only one in 2016.

While meaningful limits are meant as a legal protection, and these limits will certainly help sidestep the critical eye of proxy advisors, they have a practical function as well. Because a typical limit is about 2-3x the base retainer, it helps account for special awards or unusual situations that may warrant higher compensation for directors outside of the typical retainer.

For example, the limit would cover additional board responsibilities (i.e. a chair position, which, according to the Equilar report, receives a median $160,000 retainer on top of the base), as well as any special situations. Those may include initial awards, which are provided when a director joins the board and are often larger than base retainer in order to provide immediate vesting in the company. They may also include pay for M&A committees or other special committee formations that arise outside of the expected scope of board service to respond to a particular issue.

Alphabet provides an example of how “meaningful limits” are used. The company has a director pay limit of $1.5 million, and in 2016, the company awarded just over $1 million to a new director, Roger Ferguson, as an initial grant of stock. The explanation, as disclosed in the company’s proxy (p.37), is below:

“Roger was appointed to serve as a member of our Board of Directors and the Audit Committee effective June 24, 2016. In connection with his appointment, he received our standard initial compensation for new non-employee directors consisting of a $1.0 million GSU grant made July 6, 2016 (the first Wednesday of the month following his appointment).”

And here’s the note from the previous page, which outlines the limit:

“Under Alphabet’s 2012 Stock Plan, the aggregate amount of stock-based and cash-based awards which may be granted to any non-employee director in respect of any calendar year, solely with respect to his or her service as a member of the Board of Directors, is limited to $1.5 million.”

So, while Alphabet’s board base retainer was $425,000, the director pay limit is just over 3x that amount because the company provides a standard, one-time initial award of $1.0 million to ensure directors are immediately vested. The limit has been approved by shareholders, and therefore there is transparency around the practice.

Though the lawsuits may be subsiding, the new ISS policy may have meaningful impacts on compensation committee scrutiny and director approvals. Boards must continue being open and transparent about their pay practices in order to ensure that their investors understand how director pay aligns with shareholder value.

“If ISS sees a pattern of two or more years of excessive director pay in relation to peers of similar size and complexity, they might recommend a vote against those responsible,” said Ron Rosenthal, a lead consultant with Meridian, during the Equilar webinar.

Generally, one reason why we have seen base retainers rise over the past few years is to acknowledge the increase in time commitments for directors. In the past, board members would be paid “meeting fees” for their attendance at quarterly meetings, but since directorships have become more of a full-time job given the rate of change and the “always-on” nature of today’s corporate environment, the ad hoc payments for meetings make less sense, since what can be constituted as a “meeting” is less clear. That said, in the cases where additional compensation is warranted, the limits allow some discretion. While they are a legal protection, they also have practical applications while explicitly assuring shareholders of a reasonable cap on director compensation.

Endnotes

1The list of 100 companies for the study was sourced here. Names were removed from the charts but may be provided upon request.(go back)

Print

Print

One Comment

Delaware Supreme Court reversed the Chancery Court last week so meaningful limits might not work any more.