Casey Aspin is Communications Director at Preventable Surprises. This post is based on a recent publication authored by Ms. Aspin. Related research from the Program on Corporate Governance includes The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Scott Hirst, and Social Responsibility Resolutions by Scott Hirst (discussed on the Forum here).

Investors stampeded into passive strategies after the 2008 financial crisis, triggering an intense concentration in control of US assets. The top five fund complexes managed almost half of the $19.2 trillion sitting in mutual fund and ETF accounts in 2016, according to the Investment Company Institute. [1]

With increased control of the stocks and bonds of corporate America comes increased scrutiny of how investors use their leverage with the companies whose stocks they own. This is particularly true during proxy season, when the votes cast by the largest investors can conflict with the wishes of the clients whose proxies they are voting, raising questions about fiduciary duty.

After BlackRock and The Vanguard Group supported shareholder resolutions at Exxon and Occidental seeking increased disclosure of climate risks, the media hailed a shift in investor attitudes toward risk, specifically the risk of fossil fuel reserves being stranded by emissions-reduction targets. However it is the coal-dependent energy utilities in the US that are responsible for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions, not oil and gas producers. The utility sector has fought emissions controls for decades, while opposing efforts to introduce renewable technologies. Its poor record on emissions prompted shareholders to put forward resolutions at nine carbon-intensive utilities in 2017.

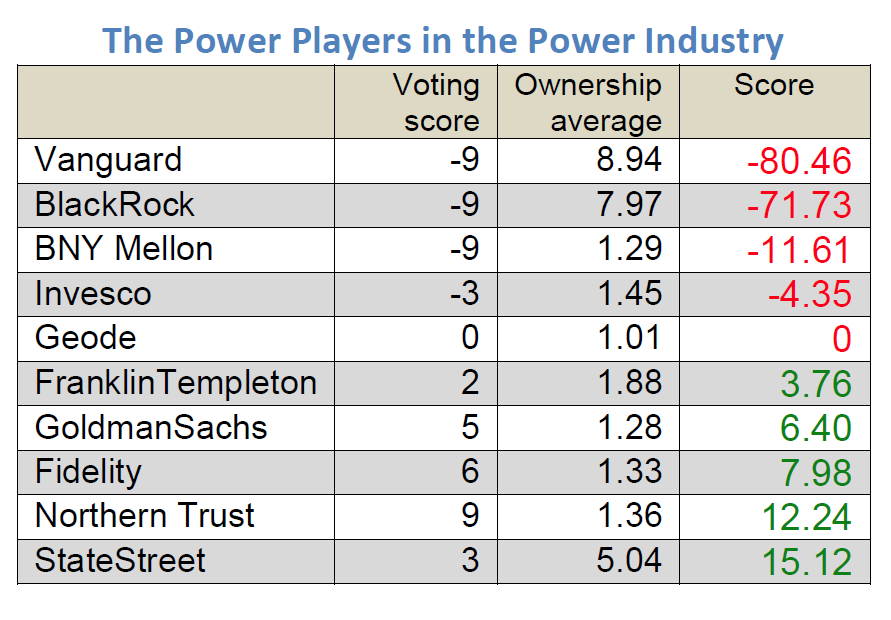

The research report I authored scored the ten largest utilities investors on how they voted on these resolutions. Vanguard and BlackRock, the two largest investors, voted against all nine resolutions. In response to my questions, both asset managers provided statements expressing a preference for private engagement with utility boards over public proxy votes. This strategy provides no transparency on what, if any, commitments utilities made. The third-largest investor, State Street Global Advisors, largely supported the resolutions. The chart below shows each company’s score, which reflects the votes of underlying funds and the company’s average ownership position.

The scoring exercise puts in relief a wide divergence of investor views of the importance of transparency around climate risk management, despite recommendations by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure that all publicly traded companies provide detailed climate risk disclosure.

The report offers a detailed profile of each company’s fund-level voting record and ownership stake in each of the nine utilities. It includes excerpts from investment firms’ proxy voting guidelines, allowing asset owners to compare asset managers’ public positions with their voting records.

The report also conveys the degree of ownership concentration among top ten firms, which ranges from 25% to 40% at the nine utilities. Concentration rises significantly if shares owned are calculated as a percentage of shares voted at the annual general meeting rather than as a percentage of shares outstanding, due to non-voted shares. Due to their size, either Vanguard or BlackRock could have changed the outcome of all eight failed resolutions.

The report also offers interviews with executives at two investment firms that supported the resolutions, State Street and Legal & General Investment Management. Both agreed that the current pro-fossil fuel environment in the Trump White House has no bearing on their stewardship activities, due to the long lead time of capital investments and the rapid fall in renewable generation costs.

Investors have a fiduciary responsibility to prevent or mitigate systemic risks, which we define as unpredictable, interconnected, and pervasive. Climate change is just such a risk, requiring forceful stewardship that includes public support of shareholder resolutions at laggard utility companies. To only pursue behind-closed-doors engagement with investee companies fails on three counts:

- It lacks transparency, accountability, and meaningful metrics.

- It fails to send a public signal of dissatisfaction with business as usual.

- It raises questions of conflicts of interest. Research by the 50/50 Climate Project has shown the largest investors receive millions of dollars in fees from the energy companies where they have sided with management and where their competitors are, increasingly, voting against management.

In a perfect world, shareholders would table more-ambitions resolutions asking utility companies to disclose their plans for transitioning to a 2°C-aligned economy. Transition plans would include emissions reduction targets and show how capital expenditures, compensation packages, and public policy efforts would align with those targets. The more-modest 2°C scenario tests remain in vogue, however, for three reasons: Trump administration resistance to the climate agenda; the SEC’s ordinary business exclusion, which could make the resolution difficult to defend; and the failure of scenario resolutions to gain acceptance among a majority of investors.

Endnotes

1https://www.ici.org/pdf/2017_factbook.pdf(go back)

Print

Print