Aaron M. Levine is an associate at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP and Joshua C. Macey is a law clerk for Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III. This post is based on their recent Note, recently published in the Yale Law Journal.

In this Note, recently published in the Yale Law Journal, we show that Dodd Frank’s compliance costs have furthered the Act’s goal of reducing systemic risk. Specifically, our article analyzes the all of the spinoffs and divestitures that have occurred at eleven systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) since Dodd-Frank went into effect in 2010 and documents the extent to which the Act’s compliance costs have led SIFIs to shed business lines of their own accord in order to reduce the costs of complying with Dodd Frank. The evidence reveals that regulators can adjust Dodd-Frank’s costs in response to the perceived riskiness of specific business units, and that SIFIs can respond to these adjustments by divesting the business lines that caused their compliance costs to increase—that is, SIFIs’ riskiest lines of business. In this way, Dodd-Frank has had an effect analogous to that of a Pigouvian tax. We call this a “Pigouvian regulation.” Our analysis thus challenges scholars who bemoan the Act’s “costly and burdensome regulations” for “failing to address key factors widely acknowledged to have contributed to the financial crisis.”

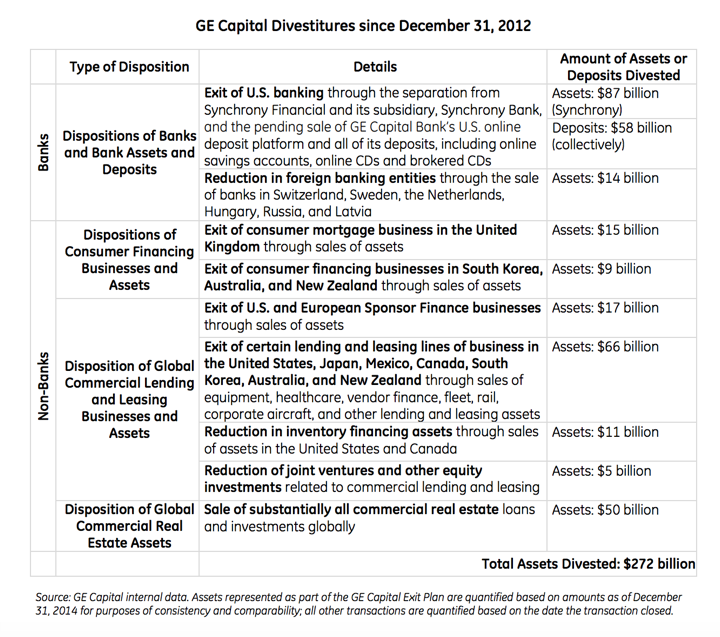

Complying with Dodd Frank is costly because it forces banks to raise additional Tier 1 capital and undergo annual stress tests and other sorts of increased scrutiny following an FSOC determination that a non-bank financial institution is systemically important. These rules are ostensibly intended to make financial institutions more resilient to economic downturns, and in some cases SIFIs have chosen to comply with these regulations. In other cases, however, SIFIs have chosen to shed the risky assets that increase their compliance costs in order to make themselves less systematically important. Such asset-shedding can be viewed as the Pigouvian component of Dodd Frank. The most familiar and dramatic example is GE, which divested itself of approximately $300 billion assets in order to shed itself entirely of its SIFI designation.

In short, we show that Dodd-Frank grants regulators discretion to ramp up (or down) these compliance costs over time, and that it therefore provides them with powerful tools to induce SIFIs to become less systemically important. We conclude that Dodd-Frank’s compliance costs should not be viewed merely as an unfortunate ancillary effect of the law. Rather the costs of complying with Dodd Frank serve as a regulatory tool that supports the Act’s core purpose of reducing systemic risk by enabling regulators to incentivize SIFIs to divest themselves of their riskiest assets. Regulators have used their power to impose costs on SIFIs to made financial institutions safer.

While GE’s divestitures allowed it to shed its SIFI designation, this option is not available to bank SIFIs because banks are automatically designated as systemically important if they have more than $50 billion in assets. However, the compliance costs faced by SIFIs increase as they become larger and more complex, and as they invest more heavily in certain businesses.

To substantiate our hypothesis that Dodd-Frank has a Pigouvian effect on large financial institutions, we used the Thomson ONE database to compile data for ten SIFIs. Thomson ONE houses a comprehensive catalogue of mergers and acquisitions transactions. For each SIFI examined, we considered all announced spinoffs, divestitures, and other transactions in which the SIFI reported that it had shed assets between July 21, 2010—the date Dodd-Frank was signed—and December 31, 2016. We surveyed only transactions in which the SIFI or one of its subsidiaries was the target company. We further narrowed the set to deals that were designated as “financial.” We did this to exclude, for example, certain real estate deals, share repurchases, and other deals that clearly unrelated to the costs of financial regulation.

We then manually analyzed all of the remaining deals to determine which transactions were likely caused by efforts to reduce the costs of complying with Dodd-Frank. We based these determinations on contemporaneous news reports, company press releases and regulatory filings, and government regulatory reports. Where Dodd-Frank’s compliance costs played a role in a divestiture, we determined which elements of Dodd-Frank were responsible, and we tried to explain why.

There are difficulties inherent in the compilation of data sets like ours and especially in the structured, yet admittedly subjective, coding scheme that we applied. In order to avoid having such methodological issues cast doubt on our findings, we focus on (and further substantiate) those transactions for which the nexus to Dodd-Frank’s compliance costs are clearest.

Because it is not certain that the data set contained all divestitures (some small or private transactions may not have been included, for example), and because many transactions fall in a grey zone and were likely motivated by a combination of market conditions, compliance costs, and command-and-control regulations, we cannot calculate the total number of divestitures that resulted from Dodd-Frank’s Pigouvian effects.

We do, however, demonstrate that the effect has been dramatic. Our analysis shows that SIFIs have divested themselves of many of the business lines regulators regarded as being excessively risky, and they did so in direct response to regulatory decisions to increase the costs of continuing to engage in risky transactions. Financial regulators have thus been using Dodd-Frank, which ostensibly rejected a market-based regulatory approach in favor of command-and-control rules, to nudge SIFIs out of risky activities.

Consider bank commodity holdings. Dodd-Frank requires large investment banks, especially Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, to raise additional Tier I capital in order to continue holding certain types of physical commodities. Rather than raise this capital, the investment banks decided to sell a substantial amount of their physical commodities holdings. The following Morgan Stanley and JP Morgan divestitures are representative of our findings:

| Transaction | Firm | Date | Value | DF Compliance Costs |

| Sale of JP Morgan’s physical commodities unit to Mercuria Energy Group Ltd. | JP Morgan | March 19, 2014 | $800 million | Andy Hoffman & Hugh Son, JPMorgan Agrees To Sell Commodities Unit for $3.5 Billion, Bloomberg (Mar. 19, 2014), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-03-19/jpmorgan-said-to-agree-on-sale-of-commodities-unit-to-mercuria (“JPMorgan is selling amid concern among regulators that banks could control prices if they own commodities as well as trade them, or suffer catastrophic losses that would endanger the financial system. The Federal Reserve said in July it might force insured lenders to get out … .”)

Sarah Kent, J.P. Morgan To Sell Commodities Business for $3.5 Billion, The Wall St. J. (Mar. 19, 2014), https://www.wsj.com/articles/j-p-morgan-agrees-to-sell-commodities-trading-business-1395214861 (The sale comes amid a realignment in the global commodities-trading business as tighter regulation and capital constraints have made it more difficult for big Wall Street banks to participate in the high-cost, low-margin business. The Federal Reserve is considering whether new rules are needed to limit banks’ exposure to the commodities trading amid concerns that these activities could pose a risk to financial stability and conflicts of interest. Such pressures have triggered a series of high-profile exits from the industry …. Meanwhile, the mostly privately held commodities houses have been snapping up assets to support their core trading businesses, lock in access to supply and provide a steady income stream. Trading houses aren’t subject to regulatory capital requirements like banks are. |

| Sale of Morgan Stanley’s Global Oil Merchanting Business to Castleton Commodities | Morgan Stanley | May 12, 2015 | ~$1-1.5 billion | Jonathan Leff, Castleton Joins Oil Trade Titans with Morgan Stanley Deal, Reuters, (May 12, 2015), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-morgan-stanley/castleton-joins-oil-trade-titans-with-morgan-stanley-deal-idUSKBN0NW24O20150512 (the sale concludes the bank’s years-long effort to divest a physical trading division that had come under intense regulatory scrutiny and suffered waning profitability …. Morgan Stanley, which has been trying to sell the division for years as the Federal Reserve stepped up pressure on Wall Street to get out of the physical commodities business. |

In sum, while compliance costs are often criticized as an unfortunate side effect of good regulatory design and scholars tend to assume that compliance costs should be minimized, in the case of Dodd Frank, those compliance costs have furthered the Act’s regulatory purpose by pushing SIFIs to become smaller and less interconnected. And the financial regulators have designed the rules in a way that makes compliance costs fall most heavily on the business lines that regulators perceive to post the most significant systemic risks.

Print

Print